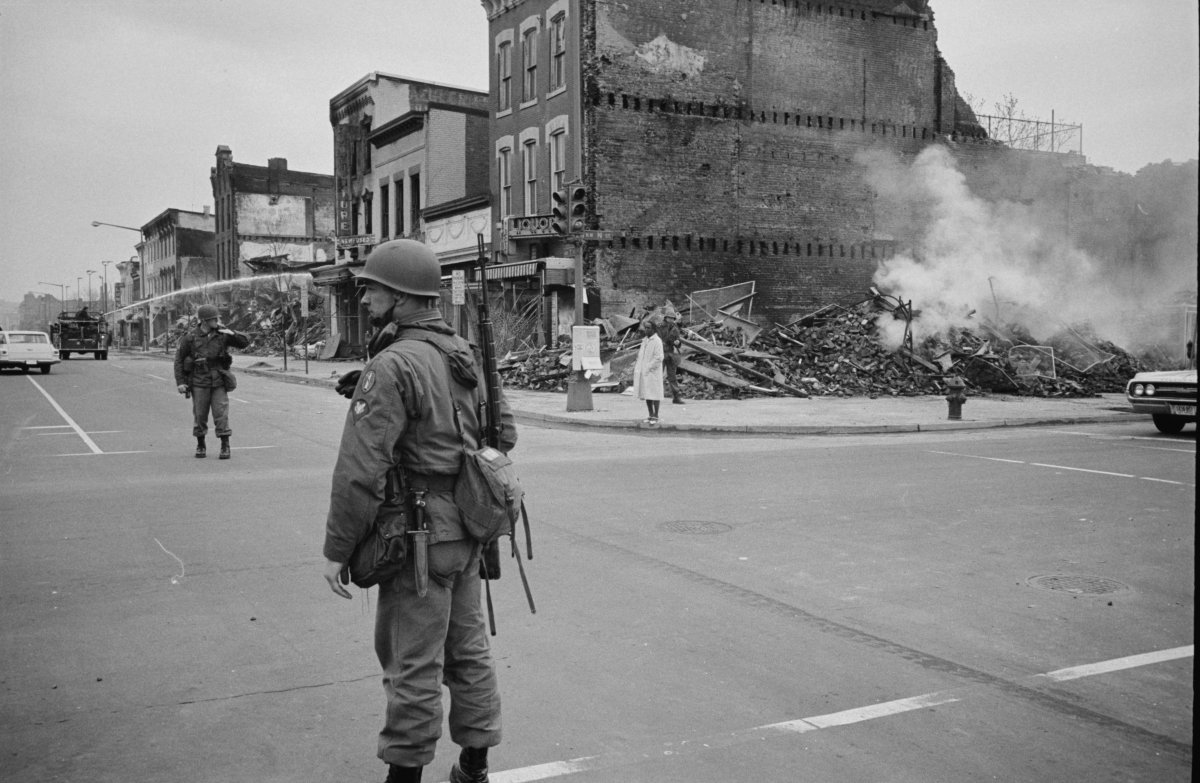

For two weeks in August 2014, the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, MO exploded in protest after police killed Michael Brown. For many it was an episode reminiscent of the “long, hot summers” of the 1960s.

The same questions reemerged: Did Ferguson erupt because of structural racism or because of the breakdown of “law and order?” Is white, affluent society to blame for such unrest or are individual actors to be held accountable? Do the police reify inequality by targeting low-income communities of color or are they the “thin blue line” separating society and chaos?

Fifty years ago, those urban riots resulted in the Kerner Commission Report. The Kerner Report pointed the finger at white society for denying opportunity to black Americans living in low-income urban centers. It called for greater federal spending on housing, education, and welfare as the remedy for riots.

Looking back on that report, Stephen Gillon argues in Separate and Unequal that the Kerner Commission, assembled by President Lyndon B. Johnson, served as “a microcosm of the unraveling of postwar American liberalism.” Gillon considers the Commission's report “the last gasp of 1960s liberalism."

Chapters One through Six of Separate and Unequal plum the origins of the Kerner Commission’s ideological fault line and discuss how it came to the conclusion that white society was to blame for the riots. Uprisings emerged in dozens of cities in 1967, culminating in Newark and Detroit. Many considered the nation to be facing a crisis of the magnitude of the Civil War and that a middle road had to be found between “anarchic violence or unprecedented repression."

President Johnson charged the Kerner Commission, named for chairman and Governor of Illinois Otto Kerner, to find that middle road. The Commission was charged with exploring both the causes of the riots and proposing ways to avoid future uprisings.

The twelve-member Commission represented the interests of mayors, organized labor, Congress, business, and law enforcement. But the Commission’s ideological binary coalesced around two figures, in Gillon’s telling: Mayor of New York City John Lindsay anchored one pole and businessman Charles “Tex” Thornton the other.

Lindsay led what Gillon dubs the “doves.” The doves insisted that racial discrimination and the diminished opportunity and poverty it produced gave rise to the uprisings. Thornton’s “hawks” were convinced that the breakdown of law and order in society were to blame—and even that communist agitators had sparked the rebellions.

The Commission’s tour of affected cities disabused the hawks of their conspiratorial fantasies and impressed upon the Commission the reality of Northern segregation and its ill effects on black communities. The Commission came to agree that white racism, and the inequality it produced, caused of the riots.

In chapters Seven through Ten, Gillon explores the solutions devised by the Commission. The job of designing them was given to David Ginsburg. He and his team agreed that a sense of powerlessness among black America was the problem. Ultimately, Ginsberg decided against more radical proposals, in Gillon’s telling, and enlisted the sociologist Anthony Downs to offer up mainstream liberal policy proposals.

Downs proposed both improving “ghetto” conditions and dispersing black housing opportunity into high-opportunity white neighborhoods. The Report called for millions more federal dollars to be spent on housing and welfare for city dwellers. The Commission, both doves and hawks, signed on to the recommendations unanimously.

Thornton might have capitulated to the liberal line. But according to Gillon, in his last (and most interesting) chapters, “conservative newspapers, Republicans, southern [white] Democrats, and disaffected whites” did not. Their favored response remained to strengthen the police, and they took offense to the color-conscious rhetoric of the Kerner Report. They viewed the “Big Government” solutions proposed by the Report as rewarding the “criminal” behavior of those who partook in the uprisings.

President Johnson could sense that the Commission had alienated conservatives. Angered by the Commission’s public plea for massive urban investment—he was already buffeted by the exigencies of the War on Poverty and the war in Vietnam—Johnson refused to approve supplementary funds for the Commission, despite agreeing with the body’s conclusion that white racism caused the riots.

After the Report, a new political era emerged in which progressive central cities were encircled by conservative suburbs and exurbs. “Big government hand-outs” were set against the “law-and-order” Silent Majority. And not much has changed since, Gillon contends.

The real novelty of Separate and Unequal lies in the numerous oral history interviews Gillon conducted with surviving Commission participants. Gillon manages to condense his vast archive into ten chapters describing every internal quarrel in exhaustive detail. We feel as we read that we are in the room with the Kerner Commission.

Gillon’s sources, however, pose two problems. First, Gillon is too uncritical of the oral histories that he cites. Second, his institutional oral history ignores developments outside of the doors of the Commission. An example of both methodological pitfalls is Gillon’s discussion of “radical” responses to the riots. Gillon’s sources swear that the federal government decided against devolving power to communities in the wake of the uprisings. Yet the Model Cities program (a modified version of the Community Action Program) was just such a post-riot devolutionary response. Model Cities expressly encouraged community participation on the neighborhood-level in social policymaking.

Gillon’s exhaustive study took a turn for the exhausting towards Chapter Eight. This is a book for hard-core policy historians of the Kerner Commission—the interested but lay reader might tire of wading through this thorough account of the Commission. Detail is all to the good, but we need salient details. The minutiae Gillon presents are sometimes irrelevant to his thesis.

Nevertheless, Gillon’s Separate and Unequal evidences anew the centrality of the “long hot summer” as a turning point in U.S. political development. The reader is convinced by the end of the book that the uprisings fundamentally altered the physics of American politics, and we are left better equipped to understand the backlash politics of the right and the carceral state we have created. Each have proved enduring facets of U.S. politics.