“Therefore go, and make disciples, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything I [Jesus] have commanded you” (Matthew 28:19 NIV).

This Great Commission found at the end of the first gospel of the New Testament laid the foundation for a dual-focused Christian mission: proclaiming the gospel of Jesus and obeying his commandments—among the most important of which was to love one’s neighbor (Matthew 22:39 NIV).

Cold War Christianity bisected this commission into two separate mandates: evangelism and social justice. The religious Right latched onto the conversion and evangelism part, while the Left sought social development and justice. During the Cold War, regional and ideological lines pulled these two further apart, resulting in a dominant narrative that equated the Right with religion and the Left with socialism and left no middle ground.

The Latin version of the Christian cross used by virtually all Protestant denominations

Historian David C. Kirkpatrick presents a third path: an evangelical Left. His book A Gospel for the Poor: Global Social Christianity and the Latin American Evangelical Left, explores the development of the understudied—and by many accounts, unacknowledged—Latin American Evangelical Left. Using a vast array of archival sources along with interviews with key actors, Kirkpatrick demonstrates how Latin American evangelical leaders found a middle ground in the Cold War context between Marxist liberation theology and the U.S. Religious Right: a theology rooted in misión integral (integral mission). He notes that while the influence of the Latin American Evangelical Left has been growing since the 1960s, Western academia is only recently awakening to this story.

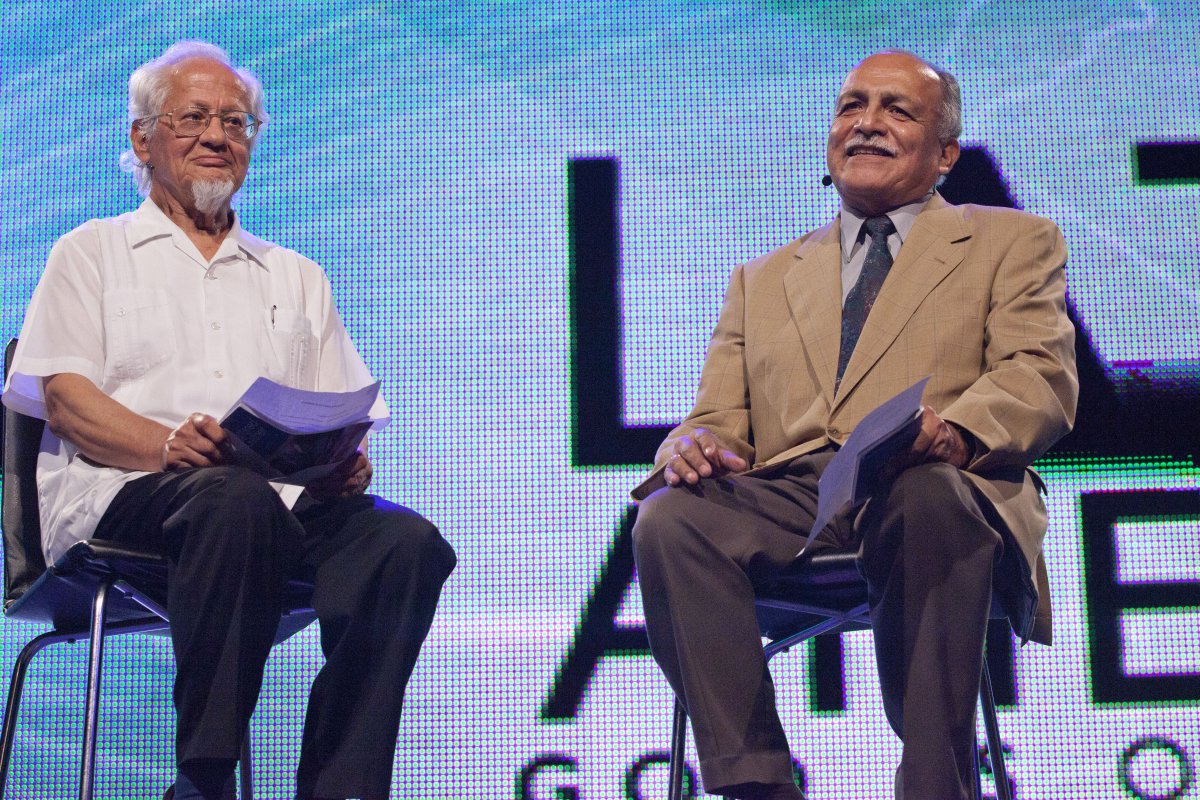

Misión integral combined the social Christianity traditionally supported by the political Left with the evangelical agenda associated with the Right. It held that biblical concepts of sin, justice, and salvation were not only personal, but deeply societal facets of life. As a result, addressing sin, seeking justice, and accepting salvation needed to be addressed on systemic, structural levels. Latin American religious leaders, including Samuel Escobar and René Padilla, spearheaded this movement which first dissected, then reconstructed mandates for social justice and evangelism.

A Gospel for the Poor begins with the Lausanne Conference of 1974, where postcolonial thought dominated the agenda and the global influence of Latin American leaders could not be ignored by Western theologians. Outcomes of Lausanne 1974 included both an indictment of white-washed U.S. Christianity and the emergence of a global network of Christian leadership with a hybrid identity that baffled many Western scholars and theologians: evangelical and Left.

In the second chapter, Kirkpatrick shows how the university setting and revolutionary atmosphere of the late 1960s set the stage for Lausanne—particularly the student movements of 1968 and the rising influence of Christian organizations. He claims that the global attention given to the protests provided publicity and a breeding ground for further action by evangelical, social-justice-conscious Christians. He goes on to consider how the Cold War shaped this religious movement and to discuss the tension between what participants see as U.S. paternalism, manifested in particular in dependency-theory policies, while being dependent on money from the U.S. A black-and-white narrative necessarily yields to various shades of grey.

The fourth and fifth chapters center on the expansion of the Evangelical Left movement and on actors who made that possible. These chapters focus on the hybrid theology of social Christianity and evangelism that make up the Evangelical Left, focusing on the work of leaders including René Padilla and Samuel Escobar.

Chapter five in particular focuses on the key role women like René Padilla’s wife, Catherine Feser Padilla, played in the movement. Kirkpatrick argues that as far as mission work was concerned, women pursued social justice issues as heavily as, if not more than, men did and therefore social justice and gender equality were not only accepted but expected by those active in the Evangelical Left. Kirkpatrick clears up any lingering confusion over the difference between liberation theology—which repelled many on the Evangelical Right—and social Christianity.

He concludes by exploring how the Evangelical Left sold its practices to the conservative Religious Right. They did so primarily through NGOs, which created depoliticized actors that gave individuals the ability to aid individuals, but avoided working through government and national channels. A Gospel for the Poor ends with a declaration of the Latin American Evangelical Left’s multilevel global influence over social issues, religious prerogatives, agenda-setting, and power brokerage for minority groups.

Insightful and original, A Gospel for the Poor is not without a few shortcomings. As Kirkpatrick notes, “context is never sufficient to explain the development of theological ideas.” Undoubtedly, writing an academic narrative about a topic as intensely personal as religion is a difficult feat. However, at its core, this is a narrative rooted in the Christian gospel and driven by people whose life work was dedicated to the teaching of the Bible. Yet, Kirkpatrick glosses over any reference to Scripture with shorthanded summaries and he neglects to cite the Scriptures upon which the movement was built. In failing to do so, he shortchanges the depth of the motivation of the leadership, the long-lasting and universal mandate for biblical social justice.

For example, when discussing the Micah Network, made of numerous well-known Christian NGOs, Kirkpatrick foregoes an explanation of the group’s mission beyond simply the pursuit of social justice rooted in the Bible. Had he quoted the verse at the core of the Micah Network’s founding—“[God] has showed you, O man, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8, NIV)—readers who may not be well-versed in Christian Scripture would be better able to understand how leaders of the Latin American Evangelical Left used the Bible to shape their mission and persist in carrying it out.

At its core, A Gospel for the Poor is a compelling narrative that tells an important story that had previously been hidden in plain sight. By giving a voice to understudied and often-ignored actors, this monograph colors the narrative, rejects the traditionally accepted, polarized, black-and-white, Left or Right binaries surrounding both Church and Latin American histories.