Frictions on the Texas-Mexico border have boiled over in 2024. But as historian Justin Salgado explains this month, the responses to those conflicts have important roots in operation “Hold the Line,” a border control effort from 30 years ago. Then as now, border enforcement efforts neglected the way the social, familial, and economic lives of those living on both sides of the border are intertwined.

In his 2024 State of the Union Address, President Joe Biden championed a bipartisan border deal as “the toughest set of border security reforms we've ever seen.” Urging Congress to pass the bill, Biden emphasized its provisions to increase the number of immigration agents and judges at the border.

He also proposed deploying advanced drug detection machines to combat the influx of fentanyl, which he claimed was responsible for the deaths of thousands of children. Biden said, “This bill would save lives and bring order to the border.”

Two months earlier, Texas Governor Greg Abbott had seized Shelby Park in Eagle Pass, Texas, deploying the Texas National Guard to apprehend migrants while restricting the federal border patrol’s access. The seizure was Abbott’s way of taking control of border crossings, which he framed as an “invasion” that the federal government failed to address adequately.

While Biden and Abbott disagree on most policy issues, they both characterized the U.S.-Mexico boundary as a site of crisis. They both suggested bolstering border militarization as a crucial step in tackling immigration and crime.

Border issues aren’t mere policy matters, of course. They can be perilous. Americans can see the consequences of this kind of deterrence in the present.

On January 11, 2024, following Abbott’s seizure of Shelby Park, a woman and two children— Victerma de la Sancha Cerros, 33, Yorlei Rubi, 10, and Jonathan Agustín Briones de la Sancha, 8—drowned while attempting to enter the United States. Despite alerts of migrants in distress during their river crossing, the U.S. Border Patrol was obstructed from entering the park by the Texas Military Department.

This conservative shift in border enforcement is not a recent development. Rather, an increase in militarization is part of an extensive history that gained momentum following Operation Hold the Line (OHL) in 1993, conducted at the ports of entry in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

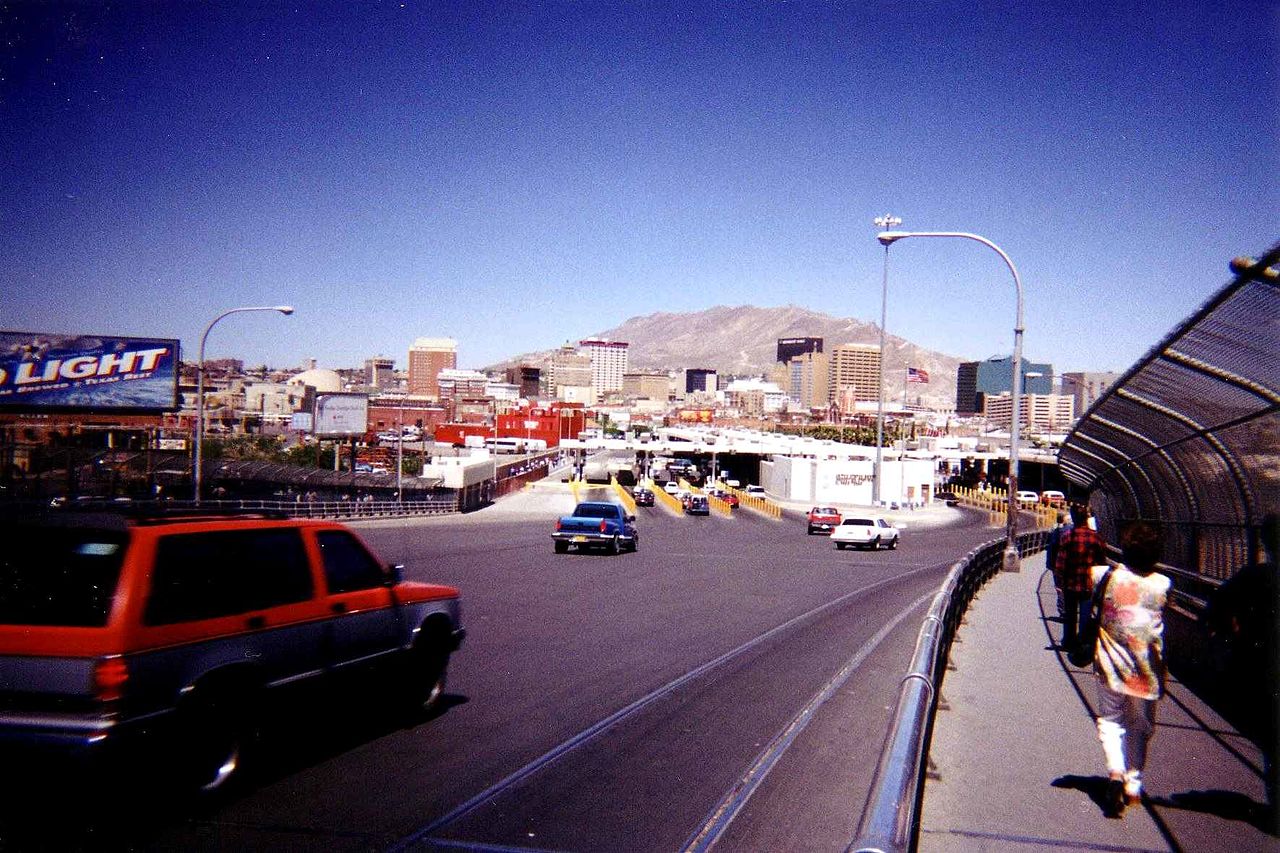

On September 19, 1993, the chief of the El Paso Border Sector enacted a blockade between the two cities to stop unauthorized immigration. It aimed to address the influx of migrants by strategically positioning agents directly on the border to deter unauthorized crossings. Since then, there has been a notable reorientation of border enforcement policy towards “prevention through deterrence,” causing challenges for those living in the cities and resulting in fatal outcomes for migrants in transit.

OHL presents a critical moment to understand the historical legacies of enforcement and militarization at the U.S.-Mexico boundary. It allows us to think about the interconnectedness of communities, cities, and other locations that share a cross-border economic, social, and cultural identity and to ask: What does the relationship between border cities tell us about border enforcement? What do the reactions to OHL teach us about current approaches to border immigration policy?

The Nature of the Borderlands

Many Americans, especially those unfamiliar with the dynamics of the border region, often characterize it in terms of unauthorized crossings and crime. Media outlets, for example, focus on the influx of Central American and Black Caribbean migrants, the admittance and settlement of immigrants, and the loss of U.S. jobs to noncitizens.

U.S. Immigration policy certainly follows this narrative.

A clear example is the Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson-Reed Act, which established the U.S. Border Patrol and limited the number of people who could enter the United States. The Act sought to control the flow of immigrants, especially those from “undesirable countries.” A New York Times article published on April 17, 1924, titled “America of the Melting Pot Comes to End,” by Senator David Reed (R-PA), a co-sponsor of the bill, demonstrates the Act’s xenophobia.

Other pieces of legislation, such as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, and the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, among others, demonstrate the hardening of the U.S. southern border in the 20th century. The region has always been subject to scrutiny, with most Americans agreeing that the border is a place where enforcement and control are necessary.

Still, most people fail to understand the vital relationship between border communities. Transnational towns have long nurtured symbiotic economic, social, and cultural relationships between countries. Though separated by a national boundary, border cities such as El Paso and Ciudad Juárez develop interdependency through work, trade, consumption of goods and services, and family and social ties.

Since 1953, the United States and Mexico have implemented Border Crossing Cards (BCCs) to permit Mexican nationals to enter the United States under specific provisions. These cards enable Mexican visitors to stay in the United States up to 72 hours for purposes such as tourism, shopping, or personal matters. Other authorized forms of entry also include work permits, which allow Mexican residents to take jobs in the United States.

However, obtaining a BCC is often difficult and time-consuming. It requires Mexican applicants to demonstrate that they have no intention of permanently residing in the United States and that they are financially secure. This process is often inaccessible for those living in the cities. As a result, many people who crossed the border did so without authorization.

Before the implementation of OHL, many people on both sides of the border had relied on one another for several decades. However, the blockade that restricted access to their city altered that relationship.

Operation Hold the Line: The Border Blockade

Operation Hold the Line, and border policy more generally, disregarded the symbiotic relationship between border cities such as El Paso and Juárez.

OHL was the brainchild of Silvestre Reyes, chief of the El Paso Border Patrol Sector. It was a bold experiment aimed at curbing the travel of migrants across the 20-mile stretch of border connecting these two urban hubs. Reyes mobilized a sizable contingent of border patrol agents—400 out of El Paso’s 650—to maintain a continuous presence along the border day and night, seven days a week.

Associating a surge in crime with a rise in immigration, Reyes proposed tightening the border. Certainly, Mexican immigration to the United States had increased in the 1980s and 1990s.

The surge was attributed to a severe financial crisis from low exchange rates, high inflation, political instability, and the economic dislocation brought on by neoliberal economic policies adopted by several Latin American countries. Many have colloquially called the 1980s “la década perdida,” or the lost decade, due to the severe financial instability that plagued many Latin American countries.

However, in his decision to implement the blockade, Reyes overlooked the connections between the two communities. When an El Paso Times journalist questioned his rationale, Reyes stated, “I don't think we need justification for doing our job.” Reports showing reduced crossings and crime rates convinced Reyes that the border experiment was successful.

Still, the far-reaching repercussions of OHL included an enduring “prevention through deterrence” policy and a new relationship between the border cities. Concerned locals, recognizing the potential impacts of heightened enforcement and militarization, took to the streets to protest it.

El Pasoans React to the Operation

At the onset of the blockade, El Paso residents expressed mixed reactions. On September 21, 1993, two days after its implementation, a few locals suggested that the border patrol was doing a good job in combatting unauthorized immigration and that they should persist as long as necessary.

One resident told the El Paso Times: “I hope the agency keeps it up from now all the time, all the way to California.” Those in favor of the operation expressed that it was about time for Mexico to understand that it needed to take care of its own.

However, others felt differently. Some said that militarism at the border did nothing to address the socioeconomic issues at the root of the problem.

Locals protested the blockade in El Paso, asserting its divisive impact on the close bond with their sister city. Many voiced concerns about the blockade’s adverse effects on El Paso’s economy alongside fears of devastating consequences for their families. Numerous residents had relatives living on both sides of the border.

Groups like Unite El Paso and the Border Rights Coalition in El Paso opposed militarization. Their efforts garnered national attention, with letters of solidarity pouring in from prominent organizations such as the Pro-Immigrant Mobilization Coalition, the American Indian Movement (AIM), and other national activist organizations.

One local group, Operation Bridge Builders, emerged in response to the blockade’s divisive impact. Founded on September 30, 1993, the organization articulated three key stances. First, it challenged the blockade’s efficacy by citing police department data indicating minimal impact on the crime rate. Second, it contended that the blockade posed actual harm to El Paso. Third, it emphasized the deteriorating relations between El Paso and Juárez.

During their first press conference, the group urged El Pasoans to reject “self-proclaimed saviors with guns and riot gear” and to put an end to the blockade. “In its place we insist on bridges,” they asserted.

Operation Bridge Builders organized a Binational Picnic at the border to show unity between the cities on Sunday, October 3. Attendees from both El Paso and Juárez converged, waving signs expressing their opposition to OHL, including one bearing the message “Todos somos imigrantes” – “We are all immigrants.”

Local activist Suzan Kern, dressed as the Statue of Liberty, stressed the imperative for a bi-national solution to elevate both cities. The picnic stood as a potent emblem of unity and solidarity, underscoring their shared aspirations for mutual understanding amidst the blockade.

In addition to local organizations, El Paso’s clergy members emerged as leaders against OHL. On October 14, the Catholic Bishop of the Diocese of El Paso, Raymundo Peña, penned a statement that resonated far beyond the walls of his churches. He spoke not of citizenship but of humanity, recognizing the plight of “day immigrants,” or those who crossed the border daily.

Peña encouraged the development of an El Paso-Ciudad Juárez metroplex that acknowledged the interconnectedness between the cities and nations. He called for a six-month to one-year moratorium to allow for an examination of the immigration procedures contributing to hardships faced by residents of the cities—though his plea was ignored.

The debate surrounding OHL intensified amid growing opposition and calls for understanding. As El Paso’s community leaders rallied against the blockade, their voices echoed across the borderlands. Despite their efforts, the implementation of militarized border enforcement continued to cast a shadow over the interconnected lives of those residing in the cities.

As the effects of OHL spread throughout the region, the Juarense community in Mexico became entangled in a struggle that endangered their jobs and, ultimately, their livelihoods.

The Juarense Response to Operation Hold the Line

OHL overwhelmingly affected those living in Ciudad Juárez. As Mexico experienced an economic crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, many Juarenses depended on the low-wage work available in neighboring El Paso. Crossing the border into El Paso had offered meager but essential work, primarily in the domestic and agricultural sectors.

The dynamic between the cities dramatically changed as a result of OHL. The new policy transformed a commute into a daunting trial, altering the familiar ebb and flow of border life.

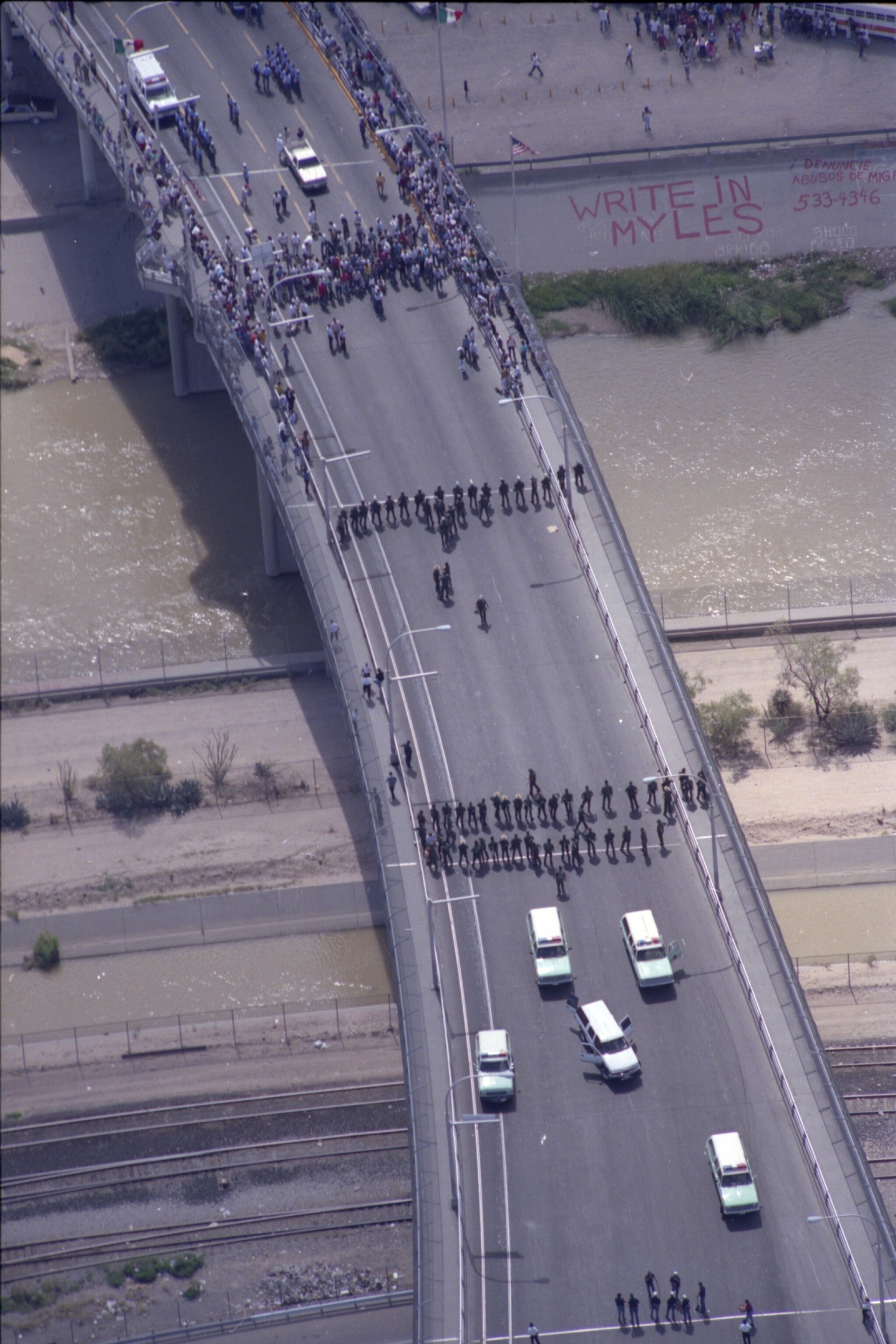

Denied entry, hundreds of Juarenses gathered at the port of entry, colloquially known as the “Free Bridge,” their voices rising in defiance. “Viva México!” they cried, a declaration of pride in the face of adversity. Growing impatient, they chanted “¡Queremos trabajar!” [“We want to work!”] to no avail.

Spirits intensified on September 22, 1993, the fourth day of the blockade. In an act of defiance, Juárez demonstrators set ablaze an American flag, a symbol of their discontent with the “yanqui” government’s heavy-handed tactics. Amidst the chaos, members of the Party of the People’s Defense Committee (CDP) joined the protests, their ranks swelling with students, teachers, farmers, and workers united in their fight for fundamental human rights in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

Miguel Besoberto, a leader of the CDP, opposed the blockade and proclaimed the resilience of unauthorized migrants who labored on American soil. “It is the undocumented people from Mexico who had strengthened the United States,” he declared. “It is the Latinos who are the ones who produce their land, who do the worst underpaid jobs, and are still treated badly.”

The architects of the blockade justified their actions by pointing to the region’s elevated crime rates and rampant illegal immigration. But in their efforts to address these issues, they did not consider the reality that numerous Juarenses relied heavily on cross-border commuting for employment opportunities.

Accounts in the local newspaper El Fronterizo shed light on these issues. Interviews with residents highlighted the significance of working in the United States and earning a salary in U.S. dollars. They also recognized that their labor was essential in sectors where Mexican labor was relied upon.

One person noted: “Many people on this side of the border receive a miserable salary that is not enough to support our families. This is why many people are dedicated to crossing into the neighboring city of El paso, where many of us go to work.” And another added: “We are not going to steal or be criminals in the United States but to ear our daily sustenance by doing work that the 'yanquis' do not want to do because they consider it humiliating for their 'blue blood.'”

Despite having no intention of staying in the United States, many Juarenses encountered bureaucratic barriers and logistical obstacles in obtaining a BCC, particularly in demonstrating their financial stability. As a result, out of necessity and perhaps in direct defiance, they resorted to crossing the border without status to seek employment. The new policy effectively labeled everyone as illegal.

In the end, the reactions of Juarenses against OHL show the need for more effective and humane immigration policies that address both legal entry and unauthorized crossings while recognizing the complexities of border dynamics.

The Enduring Legacy of the Blockade

Intended as a short border experiment to combat unauthorized immigration, OHL’s impact endures in the region.

U.S. immigration officials hailed OHL as an immediate success following its implementation, citing its role in significantly reducing apprehensions along the border. OHL became a blueprint for the 1990s increase in border militarization, a strategy known as “prevention through deterrence.” And now, high-tech surveillance technology and infrastructure at the U.S.-Mexico border have replaced Reyes’ wall of border agents.

Emerging policy heightened the presence of border enforcement in urban areas in the hopes of deterring unauthorized immigration. President Bill Clinton, impressed with the outcomes of the operation, directed the expansion of measures like OHL to be implemented at other urban border crossings.

Accordingly, Operation Gatekeeper was launched at the San Diego-Tijuana corridor in 1994, Operation Safeguard at the Tucson sector in Arizona in 1995, and Operation Rio Grande in the McAllen sector of Texas in 1997—all with the objectives initiated by OHL: to maintain a “show of force,” deter immigration, and amplify the militarization of the border.

In a press conference on February 7, 1995, Clinton lauded these initiatives, emphasizing their role in curbing unauthorized immigration and reducing crime.

“One of the cornerstones of our fight against illegal immigration has been a get-tough policy at our borders,” he told reporters. “As we speak, these initiatives are making a substantial difference. Illegal immigration is down, crime is down. And my budget in immigration strategy builds on that success.”

As a result, between 1993 and 1997, the Border Patrol’s budget dramatically increased from $362 million to $727 million and the number of Border Patrol agents increased from 3,991 to 6,848.

Additionally, Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, which reinforced the border fence between the United States and Mexico. This reinforcement even involved repurposed helicopter landing mats from the Vietnam War.

The prevention through deterrence strategy forced a change in migration flows, primarily by enhancing militarization and enforcement at urban crossings.

Migrants began to navigate dangerous desert regions and river crossings. This shift has led to numerous fatalities, with the Human Rights Watch reporting that the prevention through deterrence approach has contributed to a minimum of 10,000 deaths at the border over the past 30 years, a figure certainly underestimated given the difficulty of documenting these deaths.

The Challenges and Realities of Border Life

Over the past three decades, militarization along the U.S.-Mexico border has increased dramatically. Prospective crossers must confront K-9 searches, advanced military scanning technology, and lengthy queues that extend up to three hours as they await entry into the United States.

This wait is not merely a brief inconvenience; it has become a daily reality for individuals in line, many crossing to attend school, go to work, or be with family. Once a mere geographic boundary, the border has evolved into a challenge woven into the fabric of their daily lives.

The border operations of the 1990s offered a short-term solution but failed to address root causes and consider the multifaceted dynamics of border communities. The activism of those in El Paso and Juárez shows that border militarization has limitations and is ineffective in addressing the complexities of border security. It proved difficult and, worse, deadly.

First, as a test and then a lasting legacy of border enforcement, the architects of OHL failed to consider the multifaceted dynamics of the borderlands, resulting in tragic consequences that have claimed thousands of lives.

This history highlights the pitfalls of viewing the border region as monolithic. Thus, when Governor Abbott asserts Texas’s commitment to hold the line through his posts on X, formerly known as Twitter, and as President Joe Biden calls for stricter border measures, even using the word “illegals” to describe immigrants during the State of the Union Address, they should avoid depicting the region solely in terms of lawlessness, invasion, or crisis.

The experience of Operation Hold the Line underscores the need for nuanced approaches to border security that consider the deep historical ties and interconnectedness of border communities, the realities of cross-border commuting, and the humanitarian implications of enforcement policies.

A special thanks to Clay Howard, María Esther Hammack, and Andrea Constant for their help with this article.

Timothy J. Dunn. Blockading the Border and Human Rights: The El Paso Operation that Remade Immigration Enforcement. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009.

Kelly Lytle Hernández, Migra! A History of the U.S. Border Patrol. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Miguel Levario. Militarizing the Border: When Mexicans Became the Enemy. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2012.

Jason De Leon. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015.

George T. Diaz and Holly M. Karibo. Border Policing: A History of Enforcement and Evasion in North America. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2020.

Javier Zamora. Solito: A Memoir. London: Hogarth Press, 2022.