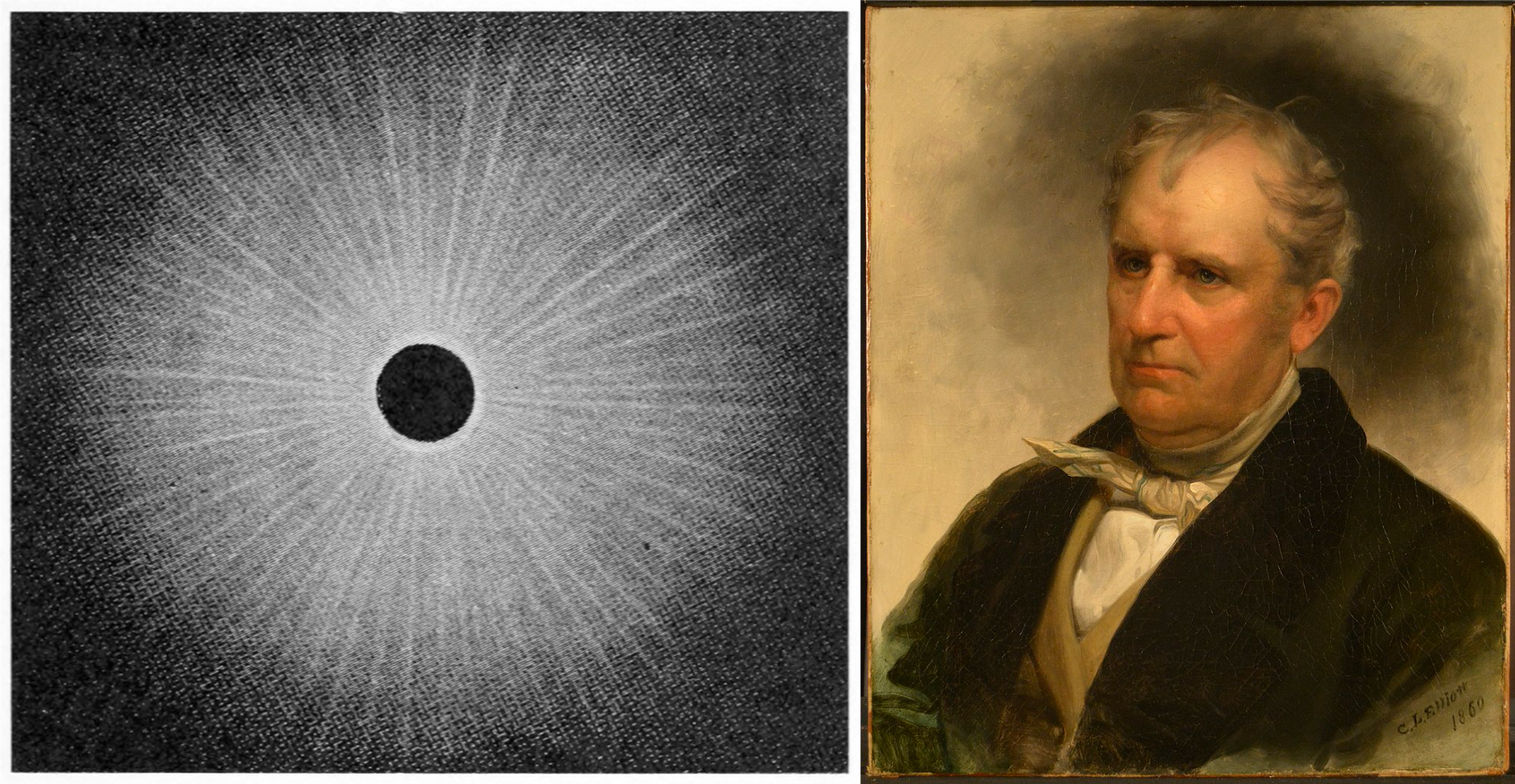

James Fenimore Cooper, the pioneering author of The Last of Mohicans (1826), was no stranger to adventure. As a youth, he served several years in both the Merchant Marine and the U.S. Navy. Later, he lived in France and traveled widely through Europe. But for all his wanderlust, his most vivid memory stemmed not from this earth but beyond.

In old age, he recollected: “I have passed a varied and eventful life, that it has been my fortune to see earth, heavens, ocean and man in most of their aspects, but never have I beheld any spectacle which so plainly manifested the majesty of the Creator, or so forcibly taught the lesson of humility to man as a total eclipse of the Sun.”

Few phenomena are so steeped in wonder as the total solar eclipse. Like the spectacle Cooper witnessed on June 16, 1806, the Great North American Eclipse of April 8, 2024, will plunge day into night. Its path of totality will cut through Mexico, Texas, the American Midwest, Pennsylvania, New York, New England, and Newfoundland.

For the sixteen-year-old Cooper by the shores of Lake Otsego, New York, the eclipse was a rite of passage, oddly familiar in outline. His close family was “joined by friends and connections, all eager and excited, and each provided with a colored glass for the occasion.” The moment inspired awe: “Three minutes of darkness, all but absolute, elapsed. They appeared strangely lengthened by the intensity of feeling and the flood of overpowering thought which filled the mind.”

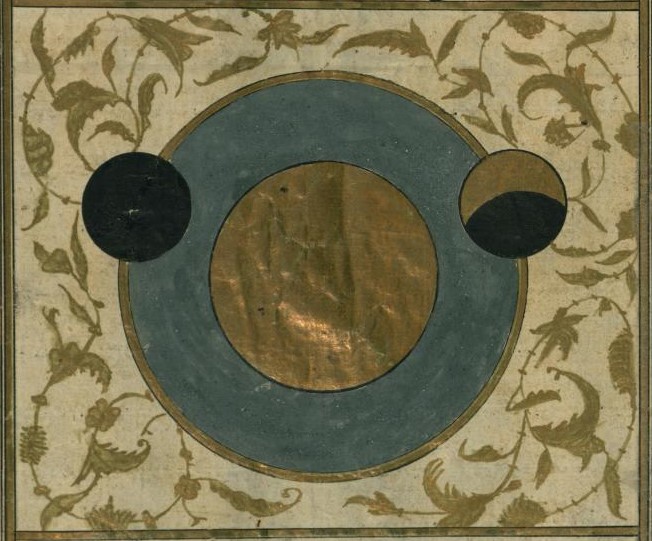

Cultures through history have heralded eclipses as portentous, ominous events. Sites aligned to solstices and equinoxes—England’s Stonehenge, Ohio’s Serpent Mound—indicate universal interest in the passage of the sun among ancient peoples. But the rarity of a solar eclipse always stands out.

More than 3,000 years ago, scribes in the Fertile Crescent chronicled the earliest recorded total solar eclipse. Dating to 1223 BCE in Syria, it was accompanied by the appearance of Mars in the sky and occasioned great anxiety. Clay tablets cryptically declared, “Two livers were examined: danger.”

Then, as now, eclipses offer perspective through their enormity. They command respect. The response of Cooper’s New York to the eclipse was no less visceral.

In his memoir, Cooper described a train of “twenty waggons bearing travellers, or teams from among the hills. All had stopped on their course, impelled, apparently, by unconscious reverence … every face was turned toward heaven, and every eye drank in the majesty of the sight. Women stood in the open street, near me, with streaming eyes and clasped hands, and sobs were audible in different directions.”

Cooper grasped the power of the moment, experiencing with new eyes “the instant when I could first distinguish the blades of grass at my feet—and later again watching the shadows of the leaves on the gravel walk.”

In part for the awe and emotion it inspired, the eclipse of 1806 found fertile reception in America’s religious landscape during the Second Great Awakening (1797-c.1840).

While Cooper himself avoided the enthusiasm of the era’s religiosity, his native region became known as “the Burned-Over District,” a place where revivals crossed paths, merging like wildfire. Upstate New York produced such utopians as Shaker matriarch Ann Lee, Mormon founder Joseph Smith, and William Miller, self-styled prophets enthused by the supernatural.

Nor was this Burned-Over District a mere backwater, but it reflected the booming nation—a “psychic highway” connecting to the frontier via the Erie Canal and other navigable thoroughfares.

Interestingly, religious leaders influenced by the American Enlightenment treated the eclipse more ambivalently, warning against popular zeal while emphasizing the hand of divine providence. Joseph Lathrop’s Sermon Containing Reflections on the Solar Eclipse reflected this balance.

Insisting the eclipse was “not an omen of any particular calamity,” the New Englander nevertheless depicted it “as an emblem of national judgments,” foretelling “political darkness” on a sinful people. “Thus saith the Lord, I will darken the earth in the clear day. I will turn their feasts into mourning, and their songs into lamentation.”

The eclipse of 1806 therefore transpired at a critical moment, when the awesome power of heavenly spectacle crossed a young American republic. As explorers William Clark and Meriwether Lewis returned overland from the Pacific, lexicographer Noah Webster’s Compendious Dictionary of the English Language defined an “eclipse” as “an obfuscation of a luminary, darkness.”

And in the Ohio country, a Shawnee warrior named Tecumseh and his brother, Tenskwatawa, challenged the eclipse of their own people. By then, hunger, disease, and violence plagued remaining Indian populations in Ohio: Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, and Miami among them. News that Tenskwatawa, known as the Prophet, was promulgating visions in western Ohio rang alarms for U.S. leaders. Here was an indigenous revival strangely resembling the Great Awakening.

In 1795, the Treaty of Greenville had forced the cession of Indian lands in Ohio to the federal government after much warfare. Now the same treaty grounds became a site of Indian resistance. While early American historians depicted Tenskwatawa—a one-eyed, reformed alcoholic seer—as the dark mirror-image of his sibling, the movement at Greenville owed more to the Prophet’s charismatic utterances than to Tecumseh’s military leadership.

William Henry Harrison, governor of the neighboring Indiana Territory, addressed the Prophet’s followers directly: “My Children: … Who is this pretended prophet who dares to speak in the name of the Great Creator? Examine him. … If he is really a prophet, ask him to cause the sun to stand still, the moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow, or the dead to rise from their graves.”

Harrison’s challenge backfired. The June 1806 eclipse—the last observable total eclipse in that location for over two centuries—underwrote Tenskwatawa’s defiance. Somehow foreknowing what was to come, Tenskwatawa not only predicted but also took credit for this apparent miracle.

Whatever the latest eclipse portends, 2024 is a pivotal if ominous year for celestial interlopers. Global temperatures may surpass pre-industrial averages by some 1.5°C. Wars rage in Gaza and Ukraine. An unprecedented four billion global citizens are set to vote in over 50 national elections, including a divisive U.S. presidential race.

And emerging technologies threaten to eclipse human consciousness in ways besides which the traumas of industrialization seem quaint. Contrast the colored lenses through which Cooper and his family squinted with the newly-marketed Apple Vision Pro headset: “a revolutionary spatial computer that seamlessly blends digital content with the physical world, while allowing users to stay present and connected to others.”

In an age of Augmented Reality, however, the eclipse promises a return to spectacle in its purest form, and—as Cooper suggested—a timeless reminder of our fragile place in the universe.

![]()

Further Reading

James Fenimore Cooper, “The Eclipse,” Putnam's Monthly Magazine 21 (n.s. 4) (Sept. 1869): 352–359.

Whitney Cross, The Burned-over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800 – 1850 (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1950).

Benjamin Drake, The Life of Tecumseh, and of his Brother, The Prophet; with a Historical Sketch of the Shawanoe Indians (Cincinnati: E. Morgan & Co., 1841).

Joseph Lathrop, A Sermon Containing Reflections on the Solar Eclipse, which Appeared on June 16, 1806 (Springfield, Mass.: H. Brewer, 1806).