March 2024 marks the 20th anniversary of the impeachment of former President Roh Moo-hyun of South Korea (Republic of Korea, ROK), a historic first for the republic.

The core issue was whether Roh violated the principle of “political neutrality” when he encouraged his supporters in the National Assembly to leave the liberal Korean Democratic Party—of which he had been a member—to join a new liberal political party (Uri Party, Yeollin-Uri-Dang) Roh had founded just before the National Assembly elections in 2004. Roh’s actions sparked an internal struggle among liberals and his impeachment was orchestrated as much by his fellow liberals as it was by conservatives.

Roh ultimately remained in office after the Constitutional Court of Korea failed to confirm his impeachment. The court acknowledged his technical violation of the Korean constitution, but ruled it was not serious enough to warrant removal.

Twenty years after Roh’s impeachment, Korean politics remain a bewildering mixture of personalities and principles, and personal allegiances make ROK politics seem especially chaotic for outside observers.

Since its founding in 1945, the ROK has had more than 70 political parties. Since 2004 alone, nine different parties have gained the 20 seats necessary to become a “negotiation group”—a parliamentary caucus that holds multiple privileges in the legislative process. Disputes between different factions, mostly over whether they are friendly or unfriendly towards the president or the party leader, are the most common cause of this cycle of division and integration.

Perhaps not surprisingly, of the eight presidents since the ROK’s democratization in 1987, six have founded their own political parties at some point during their careers. Except for current president Yoon Suk Yeol, all have changed political affiliation at least once. Many have changed multiple times.

But Korean politics is about more than just personalities. Principles also play a role. Korean political parties generally can be divided into “conservative” and “liberal/progressive,” or “right-wing” and “left-wing” camps. Unfortunately for the English-speaking world, these terms do not mean in Korea what they mean in the United States.

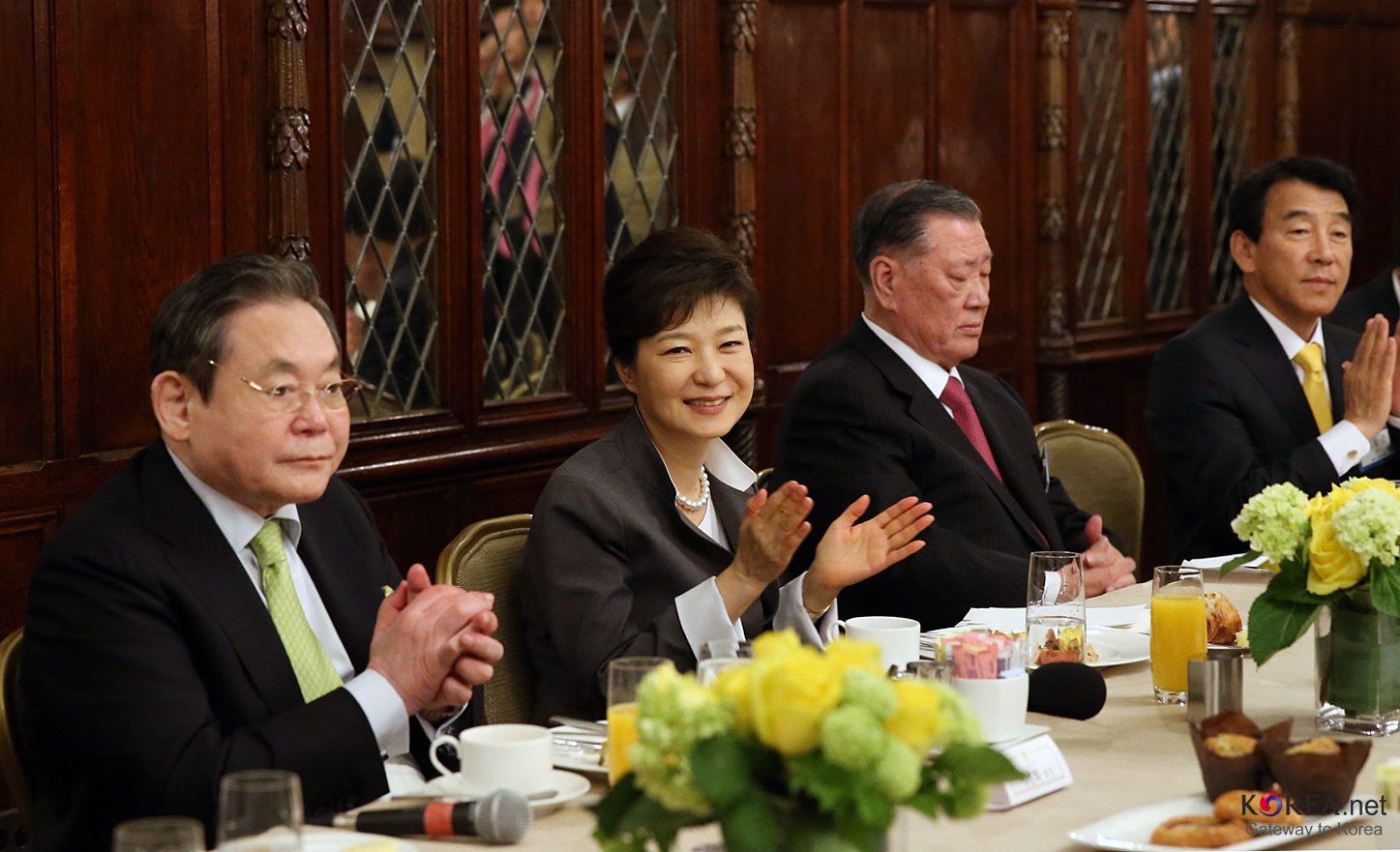

Both liberals and conservatives in Korea believe in a big central government. The South Korean executive wields significant authority over the economy, a legacy of government-led economic development initiatives that began in the 1970s.

The symbiotic relationship between corporations and government has been a hallmark of this approach, with South Korea effectively leveraging its chaebol (family-owned conglomerates like Samsung, Hyundai, etc.) to enhance its global standing. There is a broad consensus that a strong government should control key economic areas such as the real estate market, healthcare policy, and industrial regulations.

On social issues there is also considerable agreement. A majority of Koreans still oppose same-sex marriage—though that majority is shrinking. Abortion was technically illegal in South Korea until the constitutional court decriminalized it in 2021, but neither its illegality, nor its decriminalization, rose to become animating factors for any party.

Lately, issues of gender and minority rights have emerged as new points of contention, with conservatives generally hesitant to legislate policies supporting same-sex marriage, gender equality, and anti-discrimination, while liberals are more active in pushing forward these agendas. This may be a harbinger of things to come, but historically social issues have not been a dividing line between political parties.

What distinguishes South Korean liberals and conservatives are largely their positions toward North Korea, Japan, and the United States

Korean conservatives are often characterized by their strongly anti-communist and pro-American stances, deeply ingrained in the historical context of Korea's division. Since the armistice agreement in July 1953, Korean conservatives have maintained their hawkish positions not only towards North Korea but also towards nations that supported their northern neighbor during the war, specifically the Soviet Union and China.

Although the intensity of anti-communism and pro-American sentiment has fluctuated with changing geopolitical dynamics, conservative administrations have generally sought to strengthen their alliance with the United States, while adopting firm policies on North Korea. Typically, Korean conservatives endorse reinforcing U.S.-ROK military cooperation and imposing sanctions on North Korea over human rights abuses and nuclear weapons development.

Liberals, however, prefer a less hawkish approach towards North Korea, favoring cooperation without preconditions. Notable initiatives include the Sunshine Policy of Kim Dae-jung's administration, the “policy of peace and prosperity” under President Roh, and President Moon Jae-in’s efforts to facilitate dialogue between the U.S. and North Korea. Korean conservatives occasionally dabble in engagement with North Korea, but generally expect the North to meet preconditions first.

Conservatives and liberals also disagree on issues related to the Japanese colonization of Korea, including disputes over apologies, wartime atrocities, forced labor, and the sexualized slavery of comfort women.

Conservatives generally consider these issues resolved by the 1965 treaty of normalization between the two countries in which Japan provided hundreds of millions of dollars to Korea in aid and loans. Liberals argue this treaty should not preclude individual Koreans seeking reparations from Japanese companies—a view the South Korean constitutional court has upheld several times since 2018. As a result, Korea-Japan relations yo-yo with every transfer of power in South Korea.

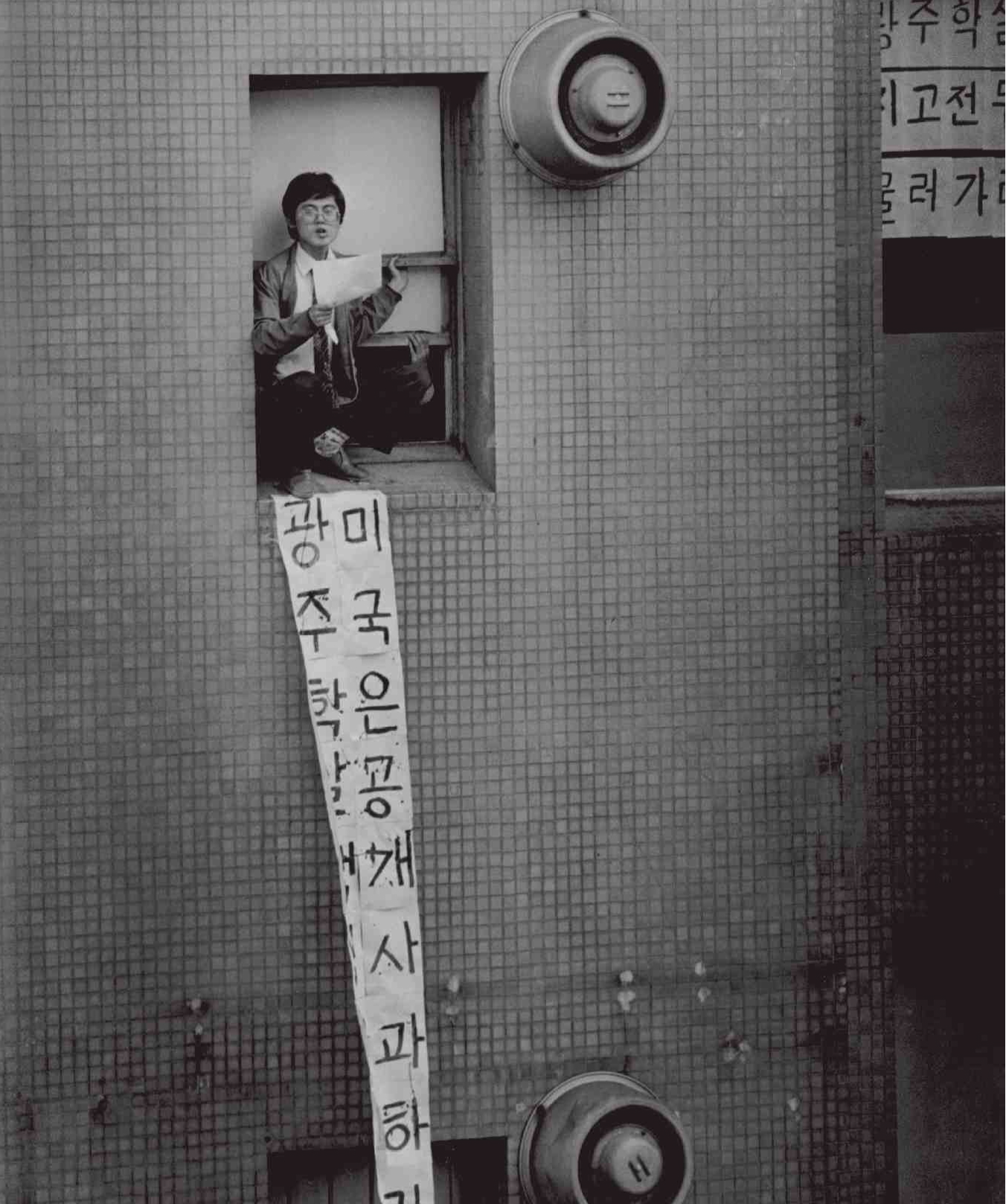

While not representing the majority, certain factions within the liberal movement strongly oppose the ROK’s relationship with the United States. This opposition is rooted in grievances over the U.S.'s inaction regarding military dictatorship and human rights violations in Korea during the 1970s (especially the Gwangju Uprising), and perceived American interference in domestic affairs.

Anti-American views have been manifested in occasional attacks on U.S. diplomatic facilities in South Korea, including the burning of the Busan American Cultural Service Building (1982), small-scale attacks on the Embassy (1989) and Ambassador’s residence in Seoul (2019), and mass anti-American protests in 2002 and 2008.

Understanding the liberal/conservative divide—as Koreans define it—and how personal allegiances constantly create divisions and unifications within these two camps is essential to making sense of South Korea’s political landscape.

![]()

Further Reading

South Korea’s Democracy in Crisis: The Threats of Illiberalism, Populism, and Polarization by Shin, Gi-Wook; Kim, Ho-ki. https://aparc.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/south-korea%E2%80%99s-democracy-crisis

Korea: A New History of South and North by Victor Cha & Ramon Pacheco Pardo. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300259810/korea/

The United States–South Korea Alliance: Why It May Fail and Why It Must Not by Scott Snyder. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/snyd20868

Anti-Americanism in Democratizing South Korea by David Straub

https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781931368384/Anti-Americanism-in-Democratizing-South-Korea