Vampires, and their various cousins, have been everywhere in popular culture for many years now. Historian Madison Chapman examines the medieval and early Modern history upon which the stories of vampires, revenants, and other such ghouls come from.

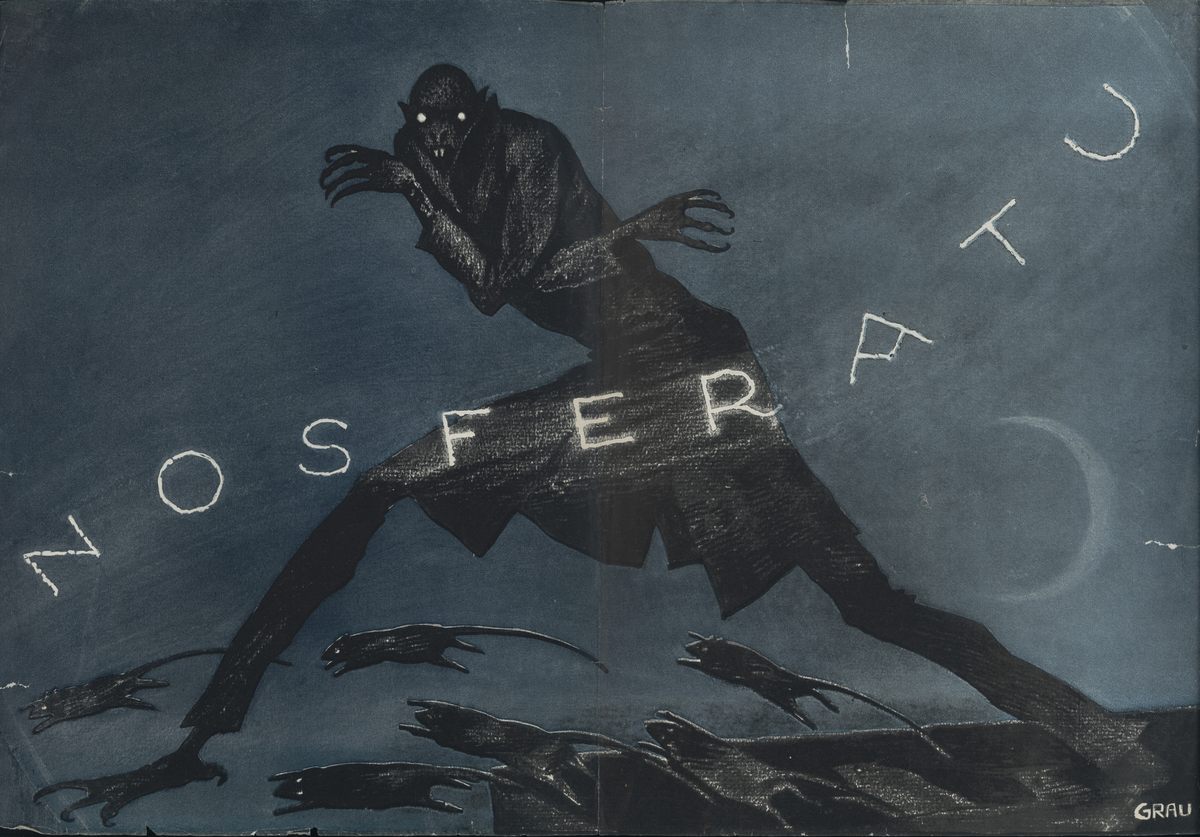

Whether or not you are a fan of all things spooky, odds are you have heard some iteration of vampiric legend. From Robert Eggers’ 2024 box office smash-hit Nosferatu to the early 2000s obsession with vampire heartthrobs like Edward Cullen and the Salvatore brothers, vampires are a seemingly immortal part of the pop culture zeitgeist.

But where do these oft-terrifying, sometimes glitteringly attractive, creatures come from?

While not an exact replica, the myths and legends of revenants, ghosts, and vampires of the late medieval and early modern periods present amazing parallels to their 20th and 21st-century counterparts.

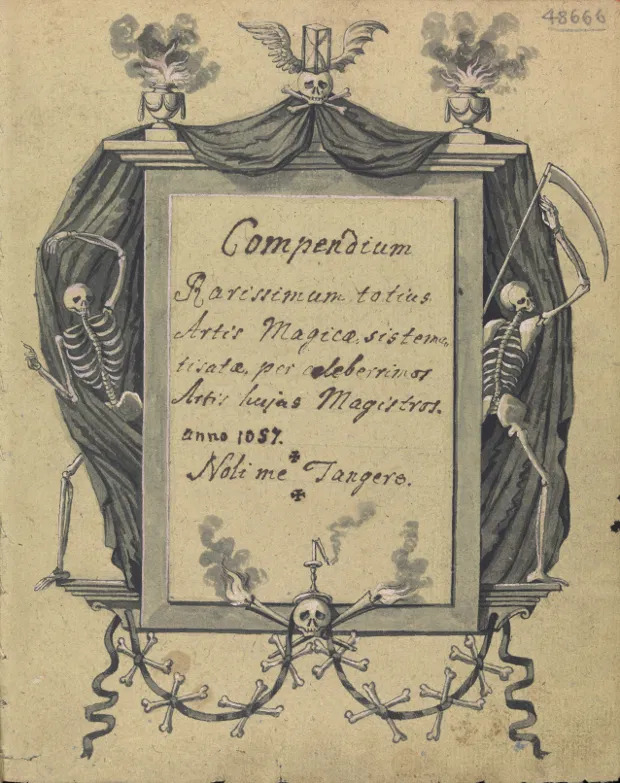

First, a note of caution. The word “vampire” did not come into existence, at least in the English-speaking world, until the 1730s. As such, it is important to note that premodern peoples did not acknowledge the existence of what we now call vampires.

However, there are legends that contain the identifiable features of modern vampirism, which can help us explain how the Draculas and Carmillas of the 19th century came to be.

Revenants

Occurring mainly from the 12th century on, stories of revenants, the restless dead who rose from their graves, can be found in European literature, from accounts of saints’ lives to histories of leaders. While revenants took many forms, common features included:

- The revenant, in life, had been particularly sinful in nature

- The revenant likely had died a sudden death without religious last rites, especially from suicide, homicide, or plague

- The revenant would torment their friends and family

- The revenant would bring pestilence upon the village

- The revenant was active after sundown, returning to their grave before daybreak

- The revenant might drink the blood of others, bloating their body and giving them a “flushed” appearance

- The revenant could only be stopped with proper disposal methods, including staking, dismemberment, cutting out the heart, and burning the remains

Scholars have extensively studied the accounts of vampire-like creatures called the draugr (revenants) of Icelandic sagas. The 13th-century Eybyggja Saga, for example, tells the story of Thorolf, a man who returns in the form of a draugr and terrorizes his family, eventually driving away the inhabitants of the Icelandic countryside and creating a veritable army of revenants.

Outside of Iceland, other European countries recorded their own horrifying encounters with the restless dead.

William of Newburgh’s Historia Rerum Anglicarum (History of English Affairs), describes an incident in which a treacherous man flees the English city of York to escape the consequences of his misdeeds. During his flight, he stumbles upon the Anantis Castle, where he accepts a position working for the castle’s lord.

The man soon marries, but, consumed by rumors about his wife’s penchant for adultery, he devises a trap. He tells her he is leaving town for a few days but sneaks back home and climbs up into the rafters of the bedchamber. Sure enough, the wife brings a young village man into her chambers with the intent to “know him carnally.”

Stupefied by his wife’s infidelity, the man falls out of the rafters and lands firmly on the ground. The lover flees, but the wife remains behind to help her husband. Weakened by the fall, the man becomes ill. When encouraged to seek his last rites, the man refuses, succumbing to his illness before repenting for his sins.

It is here that the tale truly begins. Despite the man’s Christian burial,

for issuing, by the handiwork of Satan, from his grave at night-time, and pursued by a pack of dogs with horrible barkings, he wander[s] through the courts and around the houses while all men [make] fast their doors, and [do] not dare to go abroad on any errand whatever from the beginning of the night until the sunrise, for fear of meeting and being beaten black and blue by this vagrant monster. But [these] precautions [are] of no avail; for the atmosphere, poisoned by the vagaries of this foul carcass, fill[s] every house with disease and death by its pestiferous breath.

The man’s corpse, like Thorolf in the Eybyggja Saga, returns from beyond the grave and terrorizes the area, bringing pestilence and death to each household. Those remaining abandon the village and flee.

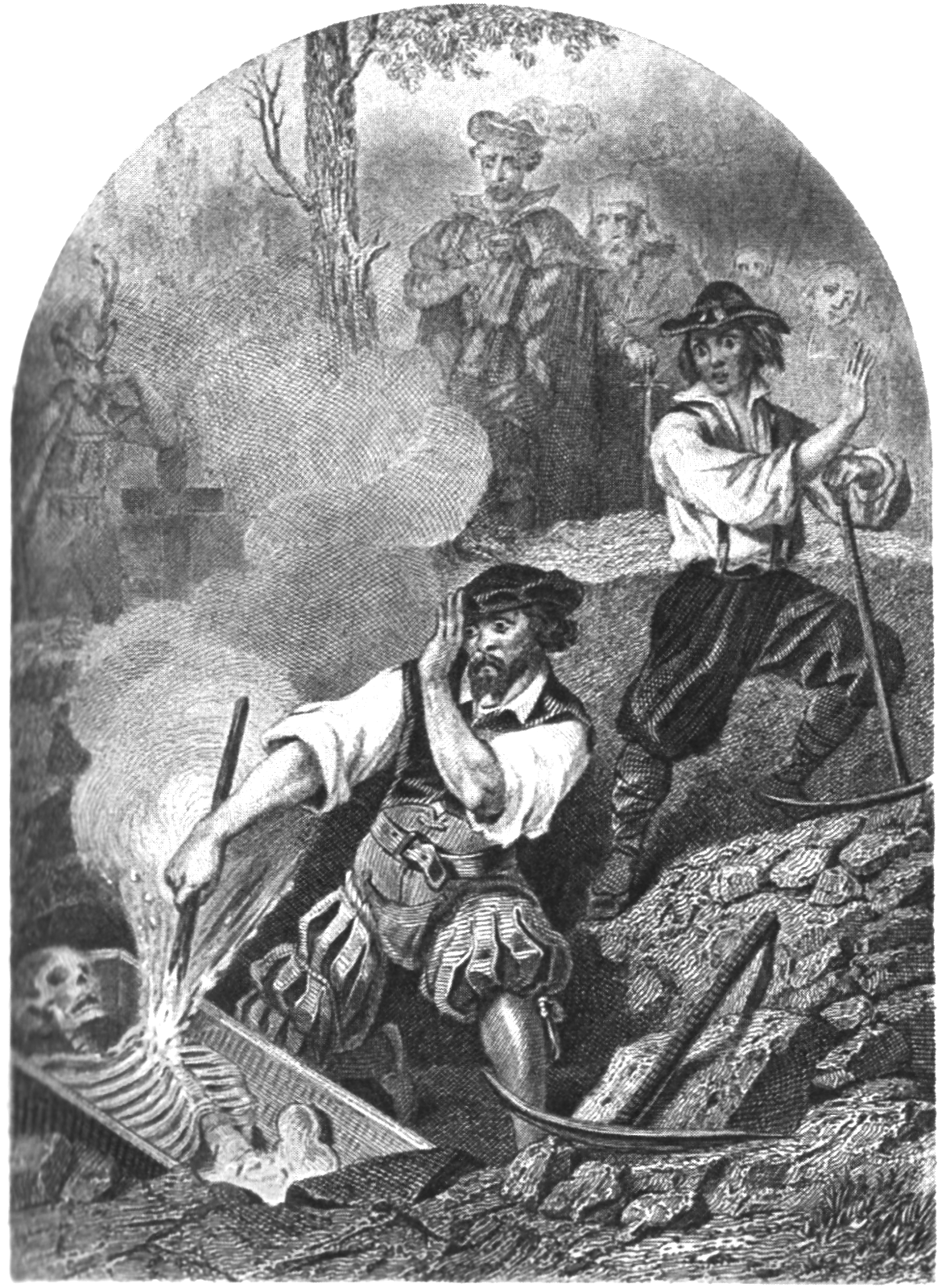

Devastated and enraged by their father’s death at the hands of the revenant, two young men decide to take matters into their own hands. While the few remaining parishioners and clergy gather to celebrate a feast day, the brothers sneak to the revenant’s gravesite and dig up his corpse. What they see horrifies them:

before much of the earth ha[s] been removed, [lays] bare the corpse, swollen to an enormous corpulence, with its countenance beyond measure turgid and suffused with blood.

Fueled by a righteous and avenging anger, the men pierce the corpse and watch as blood bursts from it like an engorged leech. Still not satisfied, the men haul the corpse from its grave, painstakingly separate it limb by limb, cut out its heart, and burn the remains on a funeral pyre.

At once, the pestilence retreats. The revenant has been disposed of, and the village, now much smaller and devastated, returns to its new normal.

More than just Ghouls: The Unfortunate Origins of Blood Consumption Fear

What inspired medieval legends of the restless dead? As with most history, no single answer suffices.

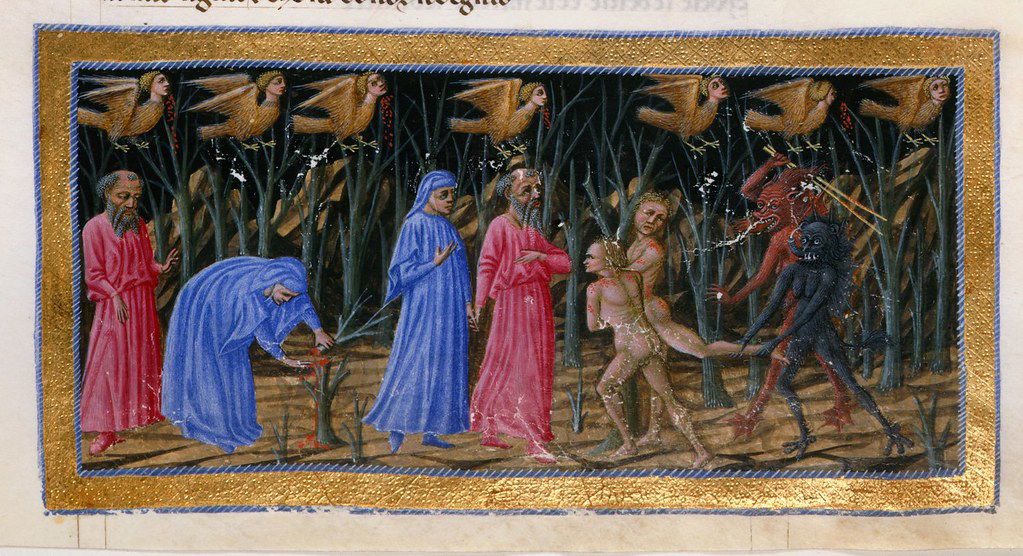

These stories grew in popularity around the same time that the Roman Catholic Church began to emphasize the existence of purgatory. Purgatory, a derivative of the Latin pugare (to purge), complicated the process of salvation.

The Heaven-hell binary became a tripartite division in which those who had yet to repent fully for their sins, but were still considered redeemable in the eyes of God, would laboriously languish in purgatory to earn their ascendance to Heaven. This concept thus inspired concern over the state of one’s soul.

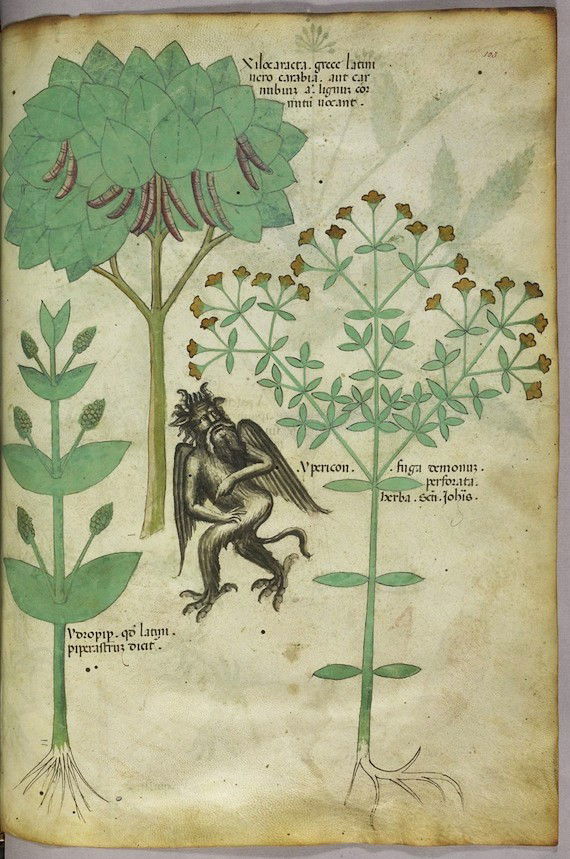

The centrality of blood to both ancient and medieval peoples provided further inspiration for revenant lore. Blood structured everything from religion to law to medicine. Unfortunately, not all blood was considered equal. At the top of the blood-hierarchy sat good, Christian men. At the bottom sat women and Jewish people.

The misogyny and anti-Semitism of the era led to the belief that women and Jewish people were not fully formed humans. As such, their humors (the fluids that made up the body: black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm) were not properly balanced, resulting in fluid leakage (menstrual cycles, in the case of women).

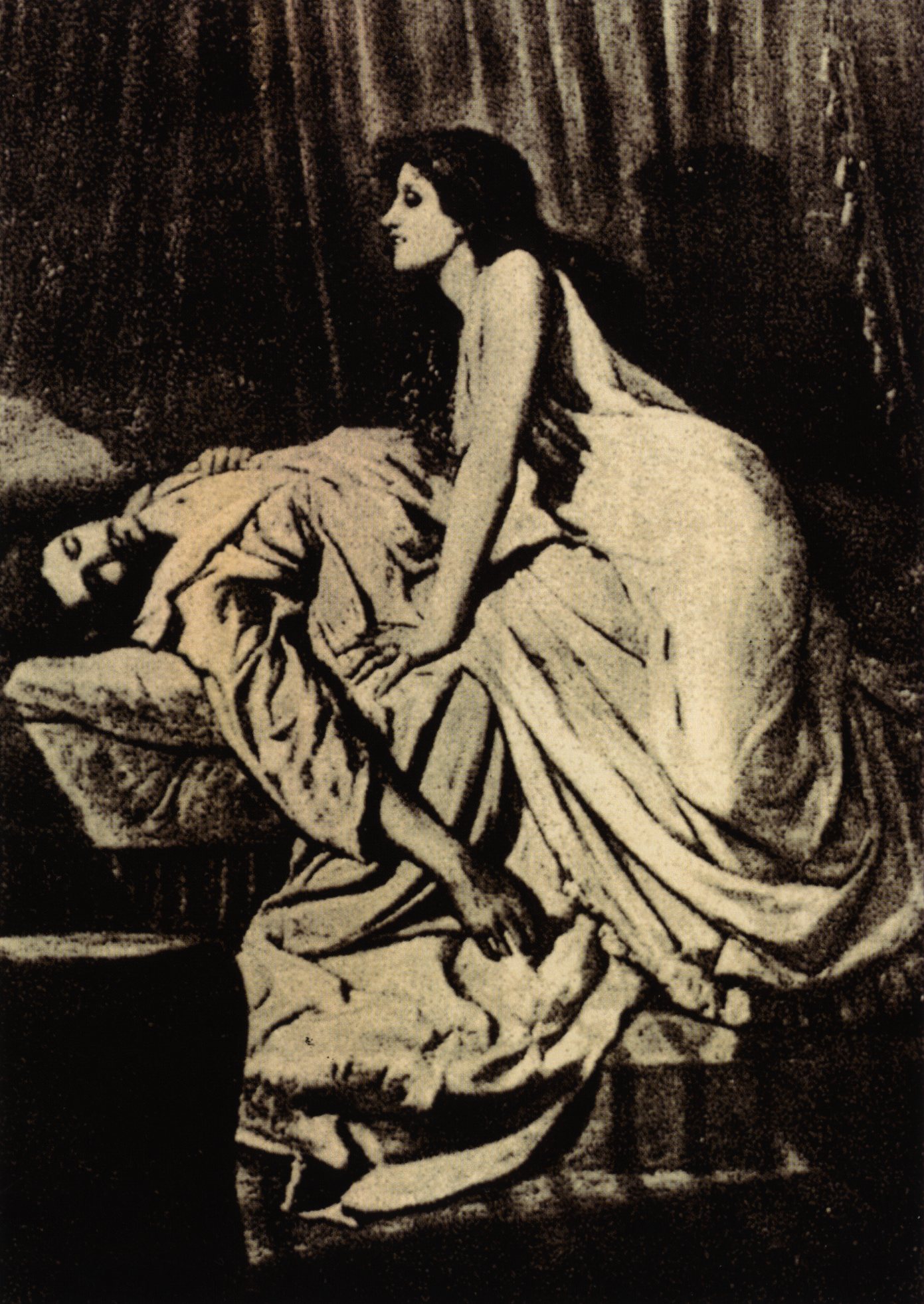

Women’s menstrual blood was thought to be a polluting substance that put men at risk. Authorities often warned that women drained the blood of men through sexual intercourse, potentially weakening the man and shortening his life span. It was believed that women needed the blood of men to sustain themselves.

Further, if menstrual blood failed to leave the woman’s body, it was possible that it would leak from her eyes. This association led to the belief that menstruating women could corrupt a mirror purely by looking at it. The mirror, once clean, would turn red and cloudy with blood.

The sermon stories of this time aimed to prove these ideas about blood, including the anti-Semitic concept of blood libel. Blood libel was the belief that Jewish people sacrificed Christian children for their blood. Relying on humoral theory, theologians argued that Jewish people, like women, needed to take the blood of Christian males to supplement their own humoral imbalance.

The Church’s Fourth Lateran Council (1215) complicated matters further in its formal adoption of the doctrine of transubstantiation, the conversion of bread and wine into Christ’s actual body and blood during the Catholic mass. Consuming the body and blood of Christ resulted in deep fear over the potentially cannibalistic act of receiving communion. Did eating Christ’s flesh and drinking Christ’s blood make all Christians cannibals? Other fears related to the quantity of the body and blood. Would supply run out? What would happen if it did?

In short, religious doctrine, medical theory, and social animosity all converged and created a society in which some bodies, namely those of women and Jewish people, were inherently lacking and thus preyed upon the blood of Christian men to sustain themselves. It was this combination of misogyny and anti-Semitism that informed stories of revenants, the restless dead, and early vampires.

Revenant Similarities to Vampires

Stories like those in the Eybyggja Saga and Historia Rerum Anglicarum bear resemblance to our modern idea of the vampire. There can be no doubt that horror writers such as Sheridan Le Fanu and Bram Stoker drew inspiration from the folkloric legends that proliferated throughout Europe during the Middle Ages.

For starters, both revenants and vampires are constrained by the rising and setting of the sun. For most modern vampires, the sun poses a deadly threat (although not for the Twilight Saga’s Cullen family, who sparkle like diamonds when exposed to sunlight).

Similarly, they are typically seen rising upright from the grave, although those believed to be a high revenant risk were buried prone as opposed to the modern vampire’s supine position.

Even the identification of dogs and wolves as the revenants’ enemies can be seen in today’s vampire stories, as in the threat posed by werewolves in the CW sensation The Vampire Diaries.

While not all revenants brought pestilence with them, many did. This aspect of the restless dead’s reign of terror can be seen in F.W. Murnau’s 1922 film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror and in Robert Eggers’ 2024 revamp. Count Orlok, the generic vampire to Stoker’s name-brand Dracula, brings plague with him as he arrives on Germany’s shores. Like the story of Anantis Castle, one by one, family and surrounding villagers succumb to the mysterious plague.

Most significantly, both revenants and vampires share in a diet of blood and death. It is important to note that not all revenants were said to drink blood, and they could be disposed of in differing ways. However, there are documented accounts of revenants who partook in the shedding and imbibing of human blood. When uncovered, these corpses, like the one in Newburgh’s Historia Rerum Anglicarum, were bloated with bloodstained mouths.

Both revenants and vampires sustain their immortality by draining the life blood of their human victims, though revenant stories make no mention of the vampire’s stereotypical sharp canines. This belief can be traced back to the ancient notion of blood as the seat of life, connected with women and Jewish peoples’ alleged need for men’s blood, and identified in the revenant’s thirst for the blood of the living.

If one finds themselves threatened by a revenant or vampire, they can turn to the most trusted, time-tested methods of disposal: staking, dismemberment, and burning. Best demonstrated by Van Helsing and Buffy Summers, piercing the corpse with a stake through the heart puts an end to postmortem activity.

When staking fails, the revenant/vampire hunter can turn to dismemberment and burning, completely removing the remains and ensuring permanent death. While not as common as staking, modern vampires may still be taken care of in such away (like James in Twilight).

Archeological Evidence for Revenant Belief

What non-textual evidence do we have of medieval revenant beliefs? Perhaps the most concrete evidence comes from archeological excavations of deviant burials. Broadly defined, deviant burials are interments of human remains that differ from the normal burial practices of a person’s religion, society, and culture.

In Catholic medieval Europe, while burial customs could differ, it was standard to bury the dead face-up (supine) in a consecrated (blessed by the church) cemetery. Deviant burials are often characterized by burial outside of sacred ground, face down (prone) remains, skeletons weighed down by stones, decapitation, or dismemberment.

Dating back to pagan antiquity, burials of this nature were performed when a society was particularly concerned about the deceased’s potential for reanimation. Denying someone a good, Christian burial was rare, but in the instances when it did occur, it was usually prompted by the deceased’s sinful premortem actions.

Burying someone facedown, or with any other deviation, served as a visible representation of the deceased’s shame. Should the dead become restless, the prone position of the corpse served to confuse the deceased and hinder their ability to crawl out of the earth to torment the living.

Even if the deceased did not come back on their own, burying someone in unconsecrated ground was to leave them susceptible to possession by the ghosts and demons that populated unconsecrated gravesites and crossroads.

The Emergence of the Brooding, Attractive Vampire Archetype

While the legends of the Middle Ages certainly contributed to the development of the modern vampire, one would be hard-pressed to find anything similar to the vampire-as-object-of-affection trope that dominates today. To understand how the Lestats and Angels (the Buffy the Vampire Slayer character, not the servants of God) of vampiric media came to be, we must look to a more recent time: the 19th century.

One of the first “romantic” vampires was inspired by the friendly 1816 writing contest that gave us Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein.

Hosted by the notorious Lord Byron in the “year without a summer,” a period when drastic climate events resulted in a decline in temperature and an overall doom-and-gloom atmosphere that lent itself perfectly to the creation of gothic literature, Shelley was not the only author to participate in this contest. Lord Byron’s physician, John William Polidori, was also moved to write. Polidori wrote The Vampyre, the tale of the lonesome, brooding, immortal Lord Ruthven.

Said to be inspired by the contest’s host, who was once described as “mad, bad and dangerous to know,” Lord Ruthven came to embody the cunning, irresistible, and dangerous vampire that would eventually culminate in the 2000s obsession with vampire love interests.

The “Reality” of Revenants: Then and Now

Much ink has been spilled over the reality of premodern revenants.

Historians have argued that these stories stemmed from disease outbreaks that transformed someone’s appearance and marked them as physically transgressive. Some have chalked the phenomenon up to a creative writing exercise.

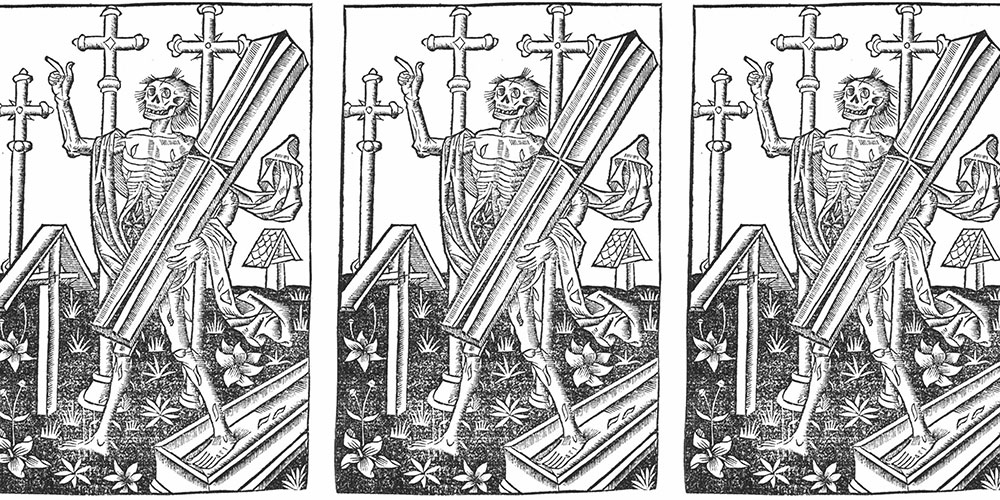

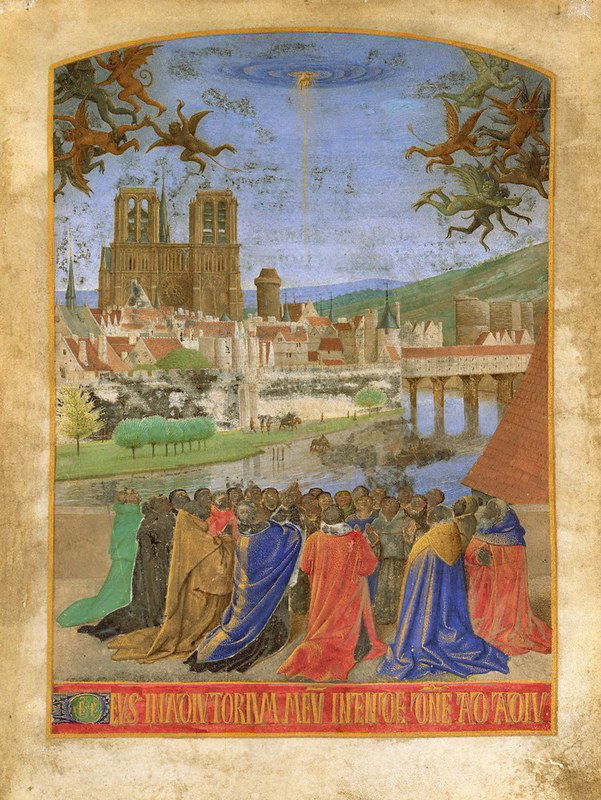

Others have linked these stories to medieval concerns about sin, death, and the afterlife, connecting the tales to the Catholic church’s gradual embrace of purgatory, the increased interest in human anatomy and dissection, the flourishing of art depicting the danse macabre (dance of death), the literature on ars moriendi (the art of dying), and the motif of memento mori (remember you will die).

In a Catholic society deeply concerned about the forgiveness of sin and subsequent ascendance to heaven instead of descendance to hell, all these surely influenced revenant legends.

Most intriguingly, some academics have connected these legends to the real-life decomposition process.

Paul Barber has convincingly laid out the ways in which modern forensic medicine can help us explain the odd behavior of corpses in revenant stories. Rather than mere storytelling, Barber suggests that revenant tales can be understood as medieval interpretations of unknown forensic phenomena.

The bloated corpses of revenants, thought to be a result of drinking blood, may relate to the tendency of corpses to swell during the decomposition process. As the body is broken down, gas builds up, giving the corpse a swollen appearance.

Likewise, those buried quickly in shallow graves, like suicide and plague victims, were more likely to be uncovered by wolves, or even to shift in their graves as a result of decomposition and rigor mortis, lending them the appearance of a corpse attempting to escape its grave.

Even the deaths of the revenant’s families and neighbors can be explained by an entirely normal occurrence: contagious disease.

As for the appearance of blood in revenant graves, Barber suggests that this can be explained away by a naturally occurring process in which a blood-like fluid is forced out of a corpse’s nose and mouth due to gaseous pressure.

Similarly, descriptions of corpses that spurt blood following puncture may indicate a release of trapped gases and uncoagulated blood, giving credence to the notion that staking incapacitates revenants. This association informs the deaths of vampires in shows like What We Do in the Shadows and films like Abigail (2024), where vampires burst into bloody matter after being staked.

As convincing as these scholarly interpretations are, our knowledge is constantly in flux. New documents are uncovered in the archives, lost items are suddenly found, and archeologists continue to find material evidence of the distant past.

Over the past few years alone, countless “new” burial sites have been uncovered.

Found near an airport in Cardiff, Wales, a medieval site uncovered in 2024 continues to puzzle archeologists and historians as they try to understand the unusual nature of the grave goods, the strange position of the remains, and the society the burial site belongs to.

These developments serve as an important reminder of our ever-growing understanding of the past. Who is to say new findings will not influence the great vampire fiction authors of tomorrow?

If our ideas of history can adapt to new information, so too can our culture.

In addition to looking to the past, we must also turn to our own society’s debates, problems, and fears in order to explain the dominance of some monsters over others. While vampires may be immortal, the shape they take can and will change in response to the climate they exist in.

New spins on classic tales, like Kat Dunn’s deliciously fresh sapphic vampire story Hungerstone and Isabel Cañas’s genre-bending take on colonialism in Vampires of El Norte, continue the tradition of the vampire as a mirror that reflects society’s own fears back onto itself. It is perhaps fitting, then, that the vampire’s individualized reflection is characteristically absent.

Barber, Paul. “Forensic Pathology and the European Vampire.” Journal of Folklore Research 24, no. 1 (January-April 1987): 1-32.

Barber, Paul. Vampires, Burial, and Death. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

Bildhauer, Bettina. Medieval Blood. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2006.

Black, Winston. “Animated Corpses and Bodies With Power in the Scholastic Age.” In Death in Medieval Europe: Death Scripted and Death Choreographed. Edited by Joelle Rollo-Koster. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Brodman, Barbara, and James E Doan. The Universal Vampire: Origins and Evolution of a Legend. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, co-published with The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., 2013.

Burton, Geoffrey. The Life and Times of Saint Modwenna. Edited and translated by Robert Bartlett. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2002.

Butler, Sara M. “Cultures of Suicide?: Suicide Verdicts and the ‘Community’ in Thirteenth and Fourteenth-Century England.” The Historian 69, no.3 (2007): 427-49.

Caciola, Nancy. “Wraiths, Revenants and Ritual in Medieval Culture.” Past & Present no. 152 (August 1996): 3-45.

Fischer-Hornung, Dorothea, and Monika Mueller, eds. Vampires and Zombies: Transcultural Migrations and Transnational Interpretations. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

Gregg, Joan Young. Devils, Women, and Jews: Reflections of the Other in Medieval Sermon Stories. New York: State University of New York Press, 1997.

Iglesias, Gabino. “Isabel Cañas’s ‘Vampires of El Norte’ elegantly navigates a multiplicity of genres.” NPR. August 18, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/08/18/1194150491/book-review-isabel-canas-vampires-of-el-norte.

Jenner, Greg. “Medieval Ghost Stories.” You’re Dead to Me. BBC Radio 4 Podcast. October 27th, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0gnwlmj.

Kaiser, Denise A., and Suzzane F. Wemple. “Death’s Dance of Women.” Journal of Medieval History 12 (1986): 333-43.

“Lord Byron (1788-1824).” BBC: Historic Figures. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/byron_lord.shtml.

Morelle, Rebecca. “Mystery of medieval cemetery near airport runway deepens.” BBC. April 22, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c241e3jr7qlo.

Newburgh, William of. “Historia Rerum Anglicarum.” In The Church Historians of England IV, part II, book V, chapters 22–4. Translated by Joseph Stevenson. London: Seeley’s, 1861.

Reynolds, Andrew. Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Sugg, Richard. Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Teter, Magda. “Blood Libel, a Lie and Its Legacies.” In Whose Middle Ages? Teachable Moments for an Ill-Used Past. Edited by Andrew Albin, Mary C. Erler, Thomas O’Donnell, Nicholas L. Paul, and Nina Rowe. Fordham: Fordham University Press, 2019.

Urbanski, Charity. Medieval Monstrosity: Imagining the Monstrous in Medieval Europe. New York: Routledge, 2023.