The conflict in the Darfur region of Sudan that captured the world's attention some years ago never really ended. Historian Kim Searcy looks at the outbreak of another civil war in Sudan by focusing on the history of the different Arab groups who inhabit the region. He argues that we need to understand these dynamics if we are to truly understand the fighting in Sudan.

War in the Sudan broke out between the paramilitary militia Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) in 2023.

According to the United Nations (UN), the war has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths. About 25.6 million people, or over half of the population, face acute hunger, including 755,000 on the brink of famine.

In addition, an estimated 10.7 million people are internally displaced within the Sudan and 2.1 million have fled to neighboring countries such as Egypt, Chad, South Sudan, and Uganda.

The warring parties are recalcitrant. The SAF has labelled the RSF as terrorists. Yasir al-Atta, the Sudanese army deputy commander, said in an interview on August 3, 2024, that the army would continue fighting until the RSF are eliminated or surrender unconditionally.

The reality of the situation is that both parties are locked in a stalemate, with each side indicating no desire to lay down their arms. The RSF is in control of most of Darfur, and its leadership and most of its fighters are from Arab tribes of this region.

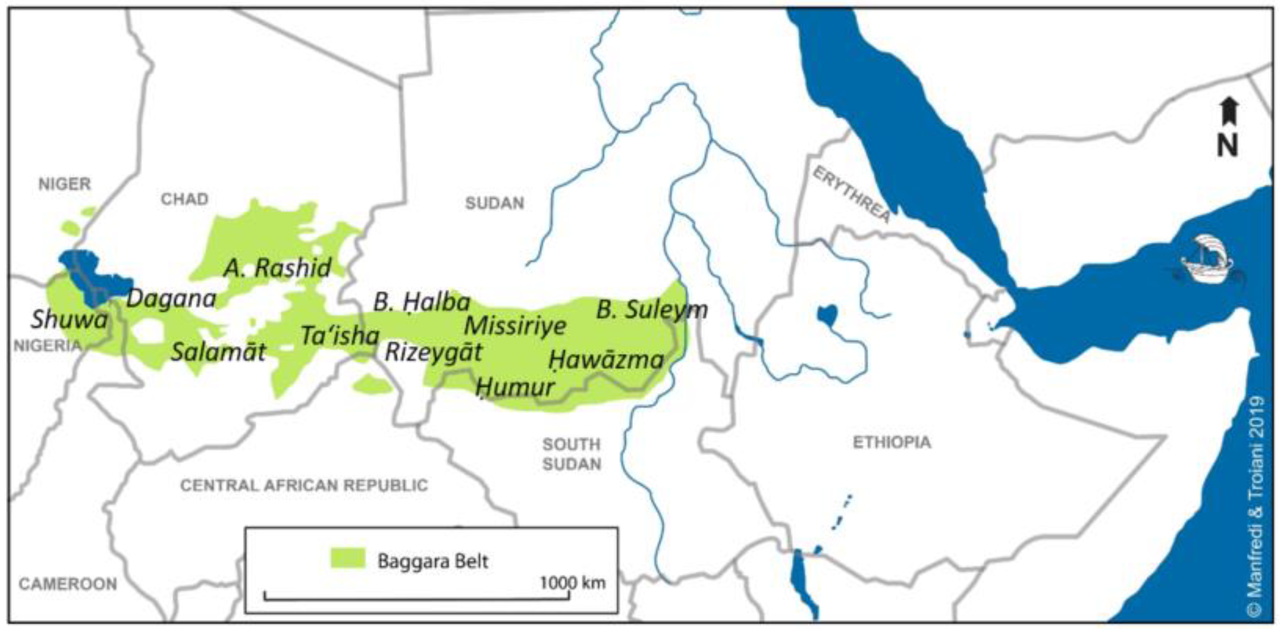

But a significant number of RSF fighters are from Sahelian Arab tribes of Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and the Central African Republic. These Arabs are known as Baggara Arabs, and their presence in the Sahel predates Islam. In order to understand the political dynamics of the war, we need to understand the history of these Arabs, who began to migrate to the Sahel in significant numbers as long ago as the 14th century.

Earliest Arab Migrations to the Sahel

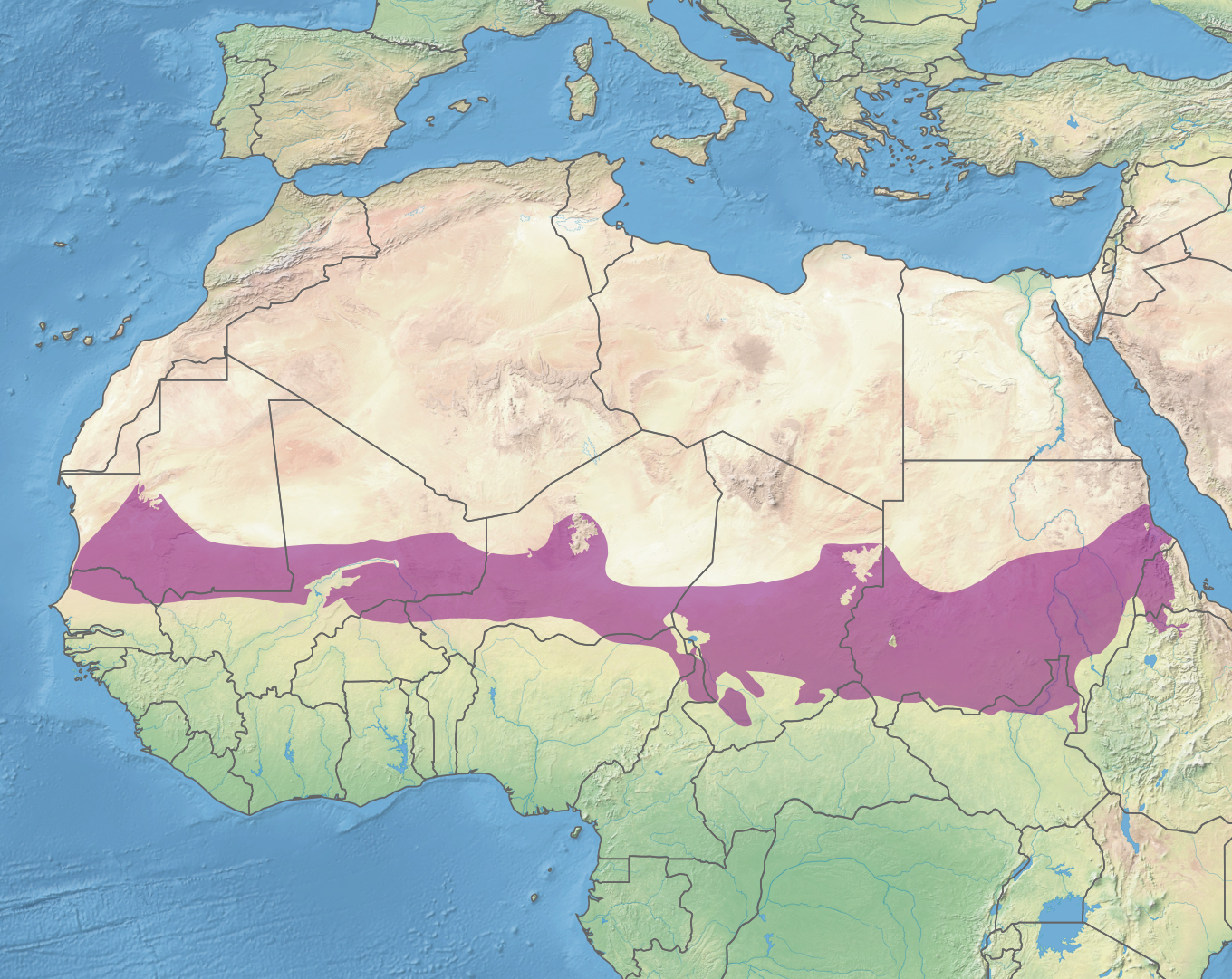

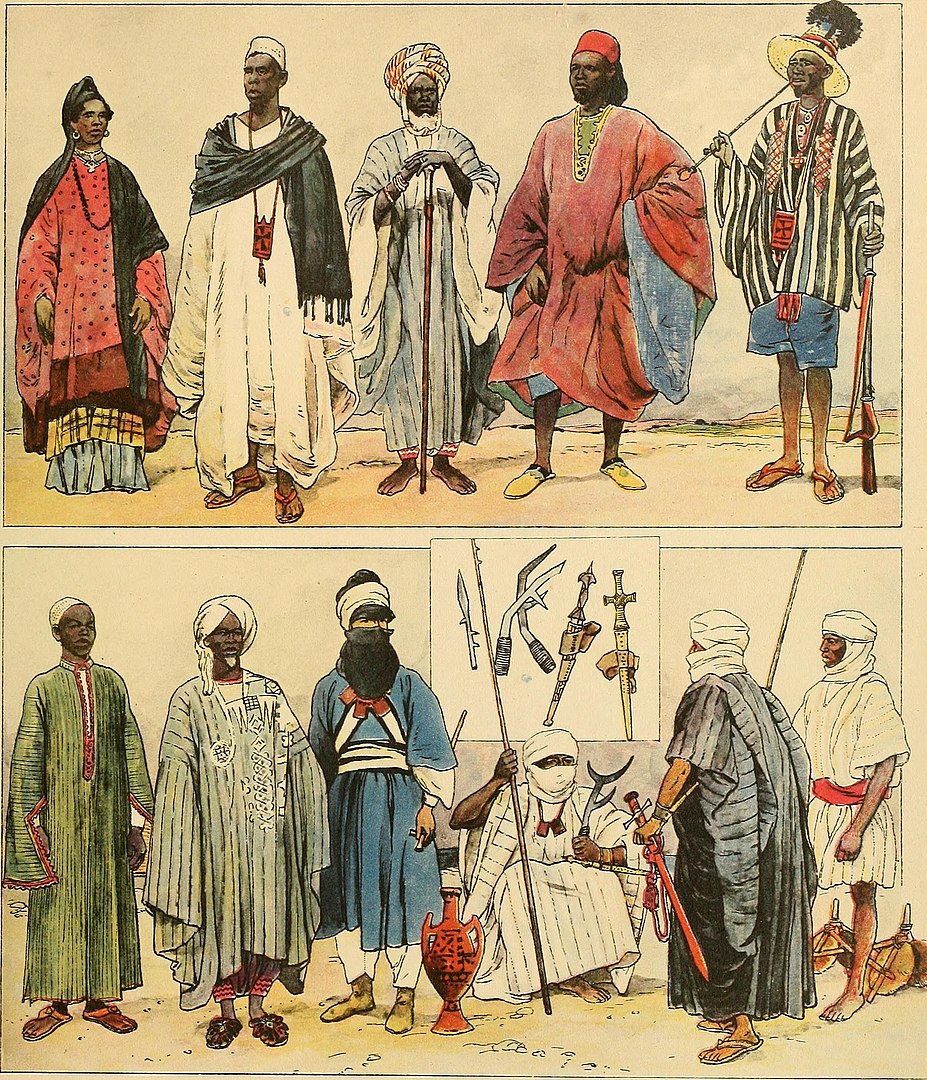

Baggara means cattle herders in Arabic, and this term refers to pastoral groups that primarily engage in cattle husbandry within the broad strip of sub-Saharan Africa known as the Sahel. The region includes parts of the six countries noted above.

The Sahel is the region of sub-Saharan Africa where the Sahara Desert in the north meets the savanna. The Sahel extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. The expanse of territory inhabited by the Baggara Arabs is known as the Baara (Baggara) belt.

The recruitment of Sahelian Arabs by the Rapid Security Forces has been influenced by economic pressures and historical migrations. The Baggara Arabs were originally camel nomads who had migrated to the Eastern Sudan from the Arabian Peninsula. Contact between the Sudan and Arabia predates Islam’s appearance in the 7th century CE.

Due to its paucity of resources, the Arabian Peninsula would at times become over-populated. This led to mass migrations across the Red Sea or into the Sinai. These migrations from Arabia followed two main routes. The first route ran from north Arabia across the Sinai desert into the Sudan; the second was either from south-western Arabia across the straits of Bab al-Mandab into Ethiopia and then north or directly across the Red Sea.

The largest number of migrations of Arab tribes occurred by way of the Sinai desert into Egypt and then into the Sudan.

A significant number of these tribes were nomadic, constantly on the move searching for pasture for their herds. Hence, by the 14th century it is almost certain that Arab tribes had penetrated as far as Lake Chad. These Arab tribes at the time were camel-nomads; subsequent arrivals traveled southward into present-day southern Kordofan and southern Darfur. Following a series of internal wars, they moved south of the Sahel from the middle of the 17th century onwards.

The ecological conditions of the savanna forced the migrants to change the base of their livelihood by either adopting agriculture or breeding cattle, or a combination of both. They became agro-pastoralists, engaging in semi-nomadic cattle breeding and the cultivation of crops, particularly millet and sorghum.

The Arab Arrival into the Chad Basin

Chad, although not classified as an Arab country, is home to some 800,000 Arabs, roughly a third of its total population. Except for a few merchant families who descend from Syrians and recent Libyan arrivals, the Arab population of Chad has largely preserved its tribal and nomadic way of life.

The ancestors of some of the Arab tribes that now reside in Chad arrived by way of the Sahara. In 1851, German travel writer Heinrich Barth described them as the most feared of all the tribes of that unsettled region. The great majority of the Arab population of Chad, however, belong to tribes that arrived there by way of the Nile and the Sudan.

After the fall of the Christian kingdom of Nubia in the 14th century, they migrated south to Dongola at the bend of the Nile, and then westward into Kordofan and Darfur. The account of this migration, based largely upon oral tradition and folklore, is told by British colonial administrator H.A. MacMichael, from whom we learn that the first Arabs to arrive from Egypt in any great numbers were those known as the Juhaina or the descendants of Abdallah al-Juhani.

Some of them settled on the sandy plains of northern Kordofan while more proceeded farther south into the savannah where they raised cattle and married native African women.

For the most part, Baggara did not remain long in Kordofan but chose to travel westward into Darfur and Waddai, where they established themselves by the middle of the 16th century. The pastoral Juhaina from west of the Nile comprised the vast majority of the Arab population. For the most part, they raided among themselves and were occupied with their herds and little else.

The Shuwa Arabs of Cameroon, Nigeria, and Western Chad.

The Shuwa Arabs of the Lake Chad region are cattle nomads who occupy a broad strip of savanna between the 10th and 13th parallels from the White Nile to the eastern Borno State of Nigeria and into northern Cameroon. Like their cousins, who settled in the eastern Sahel, the Shuwa’s ancestors were camel nomads who began arriving in the Sahel via the Nile valley in the late 14th century.

From the middle of the 17th century, they moved south of the Sahel until they struck an ecological borderline to areas beyond which the keeping of camels proved increasingly difficult. They adopted cattle herding mainly from the Fulbe, who had been migrating to the eastern Sudanic zone east of the Shari River from the 16th century on, and they became familiar with the cultivation of crops through intensive contact with the peasant populations of the area.

This transition from camel herding to cattle herding was essentially complete by 1800. The ancestors of the Shuwa migrated to the territories of Borno southwest of Lake Chad between c.1750 and 1810.

Since they originated in a semi-arid zone, they faced particularly harsh conditions in the Chad Basin because this region was one of the most humid habitats of the Sahel. Their unique strategies for coping with these environmental conditions involved special methods of keeping animals in temporarily inundated areas and a highly efficient use of grazing resources by cycles of transhumance.

The Arabic dialects of the Shuwa are homogenous and distinct from other Arabic regional dialects, such as North African, Gulf, and Levantine. The Arabic of Chad, Cameroon, and Nigeria are also homogenous, and the dialect of these regions is characterized by features that are either unique to the Baggara Arabic dialect or found only rarely outside of the region. There are some 500,000 native Arabic speakers in Nigeria and perhaps 100,000 in Cameroon. Arabic is also the lingua franca of Chad.

The Diffa Arabs of Niger

Livestock pastoralism has served as the catalyst for a centuries-long migratory pattern of these Arab groups across the Sahel. The southeastern part of Niger, specifically the Diffa region, is where many of these Arab groups settled in their treks across the central and eastern Sahel. These Arabs are comprised of Sudanese nomads primarily from the Mahamid clan of the Rizeigat of Sudan and Chad.

This Arab clan has traversed throughout the borders of Chad, Sudan, and eastern Niger for centuries following the seasons in search of suitable grazing grounds for their camel herds.

The Arab population of Niger was scant until the 1970s. A major drought in Chad in 1974 caused many of the nomadic Arab population to leave Chad and seek refuge in Niger. Another wave arrived in the 1980s, fleeing the war in Chad.

According to the World Atlas report, the Arabs in Niger now comprise 0.3 percent of the population and are the seventh largest ethnic group in Niger.

The Porous Borders of the Sahel

The countries of the Sahel are essentially colonial creations and their borders were established by either France, Britain, or the Ottoman Empire. Prior to the colonization of these regions, the borders were quite permeable and historically crossed by nomads, Arab and non-Arab alike.

The borders of the Sahel countries remained porous and unregulated well into the post-Independence period of African history. The various countries struggle to control their borders. In a region with porous borders, a political or security crisis in one country is often a serious threat to neighbors.

Before the Darfur war erupted in 2003, the region was home to seven million people mostly from three non-Arab groups: Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit. By 2007, 2.5 million were forced to abandon their homes and became internally displaced in Darfur or refugees in Chad. That same year the UN High Commissioner for Refugees reported that 30,000 Arabs from Niger and Chad had crossed the border into West Darfur.

The Arabs told an assessment team of the UNHCR they were fleeing attacks by Chadian non-Arab militias and the Chadian government. But the UNHCR was also concerned that many of these Arabs had been settling on land abandoned by internally displaced Darfurians and refugees.

Some Darfurians claimed that the government of the Sudan, then under the control of Omer al-Bashir, who was ousted from power in a popular uprising, had a goal of removing the non-Arab groups of DarFur (Darfur) and repopulating the region with Arabs from elsewhere.

James Smith, chief executive of the Aegis Trust, noted the Sudanese government was “cynically trying to change the demographics of the whole region.”

The Conflict in Darfur Never Truly Ended

The initial conflict in Darfur that began in 2003, according to the popular media, ended in 2020 with the signing of a peace agreement between the Sudanese transitional government and several rebel groups. However, the war in Darfur never ended; it merely transitioned from one phase to another, and the underlying factors remained the same.

The United Nations sent 26,000 peacekeepers to try and stop the violence in July 2007. By October of the same year, the UN Security Council called for the Janjaweed to be disarmed.

In July 2008, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court filed genocide charges against the Sudanese President, Omar Hasan Al-Bashir, and issued warrants for his arrest. The ICC found that there were reasonable grounds to believe that Omar Al Bashir acted with specific intent to destroy in part the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa ethnic groups.

The case remains in the pre-trial stage because al-Bashir has yet to be arrested by the ICC. He was, however, forcibly removed from power and arrested by the military in the wake of the Sudanese popular uprising of 2019.

The military and civilian leaders reached a power-sharing compromise that resulted in the formation of a transitional government, in an effort to move the country to democracy. On October 3, 2020, the transitional government ratified the Juba Peace Agreement, which formally ended the conflict in Darfur.

In spite of the peace agreement, the violence in the region continued. It may have lessened a bit, but according to Amnesty International, ongoing conflicts between Arab and non-Arab groups included unlawful killings, beatings, sexual violence, lootings, and the burning of villages.

For example, in 2022, less than two years after the Juba concord was signed, a wave of violence that besieged West Darfur left 200 civilians dead. The attackers, according to Radio Dabanga, were militiamen who looted valuables, burned homes, and destroyed infrastructure such as hospitals. The majority of the victims were members of the Masalit ethnic group. The Masalit are a non-Arab group whose traditional homeland is West Darfur.

According to the UN, the conflicts in Darfur intensified with the outbreak of hostilities between the RSF and the SAF in April of 2023. As of the writing of this article, the RSF is in control of the entire region except for al-Fashir, the capital of North Darfur.

Sahelian Arabs’ Role in the Current War

Lt. General Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemeti, is the commander of the RSF. He began as a junior member of the Janjaweed. Before the war in 2003, Hemeti was a camel trader. His family belonged to the Awlad Mansour, Mahariya clan of the northern Rizeigat tribal confederation.

This tribal confederation is comprised of numerous Arab nomadic clans who primarily travel across Darfur and Chad following the seasons. The northerners raise camels and the southern branch raise cattle. Even though their transhumance travels primarily involve roaming through Darfur and Chad, clans of the Rizeigat, such as the Mahamid, Mahariya, and Nuwaiba can be found in Cameroon, Nigeria, Niger, and the Central African Republic.

In 2013, Hemeti established the RSF with Sudanese government support and the militia eventually became al-Bashir’s praetorian guard. However, this praetorian guard was instrumental in removing its benefactor from power in 2019.

According to analysts at Al-Jazeera, Hemeti’s apparent ambitions are to rule all of Sudan.

Since the establishment of the Rapid Support Forces in 2013, Hemeti invited Arab fighters from the Sahel to participate in the war in Darfur, where some of them brought their families and settled in the region.

In 2015, the arrival of these fighters to Sudan increased after the RSF began to supply mercenaries to fight for Saudi Arabia and the UAE in their war in Yemen. According to security sources, the number of fighters in the RSF from Niger alone is estimated at more than 4,000 and the vast majority are from the Arab Mahamid clan, which, as noted above, is a sub-clan of Hemeti’s Rizeigat tribe.

The Sudanese writer al-Sadiq al Raziqui wrote on Al-Jazeera’s website that mercenaries returning from Yemen in 2019 were still in Sudan.

Following the initial clashes between the RSF and the Sudanese Armed Forces in Khartoum in 2023, some Arab fighters from Niger arrived in the capital city to rescue Hemeti’s forces to compensate for the losses the RSF experienced in these early battles.

In addition to Niger, countries including Chad, Mali, Niger, Central African Republic, and Libya have been identified as sources of mercenaries for the RSF in their war against the SAF.

The UN special envoy to Sudan, Volker Perthes, in an interview with Barron’s, noted there are quite a number of “armed fortune seekers,” who have traveled from Mali, Chad, and Niger to the Sudan. They are lured by pecuniary opportunities. Members of Hemeti’s family own lucrative gold mines in Darfur. Perthes added that numbers of these “fortune seekers” in Sudan “are not insignificant.”

There are estimates that the RSF have between 70,000 and 150,000 fighters with bases and deployments across the Sudan. The SAF have about 200,000 active personnel.

The commander of the SAF, General Abdel Fatah al-Burhan, informed senior figures of the Rizeigat tribe on June 13 that 70 percent of the Rapid Support Forces present in the al-Jili oil refinery 43 miles north of Khartoum, are foreign mercenaries.

This oil refinery is the largest in the Sudan and is under the control of the Rapid Support Forces. Yassar Abdelrahaman al-Atta, the deputy commander of the Sudan Armed Forces, delivered a speech on May 29, 2024, and characterized the RSF as essentially a foreign army.

Epilogue

The figures revealed by al-Burhan are unsubstantiated and the speech of al-Atta perpetuates a common trope employed by the army that portrays the RSF fighters as predominantly foreigners, essentially characterizing the war as a foreign invasion.

But this is specious claim. According to the Sudan War Monitor, there are foreign elements in the RSF from Arab tribes across the Sahel. Yet these are hardly “foreigners,” as these tribes have historically traveled throughout the region following the seasons.

The borders between the countries are permeable and unregulated, thus allowing these nomads to come and go as they please. However, due to climate change and violent conflicts in many Sahelian countries, some of these Arab groups have been enticed by the prospect of pecuniary advantages to take up arms and fight for the Rapid Support Forces in this latest Sudanese civil war.

Henrich Barth, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being A Journal of an Expedition Undertaken Under the Auspices of H.B.M.’s Government in the Years 1849-1855. Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts. London, 1858

Ulrich Braukamper, “Management of Conflicts over Pastures and Fields Among the Baggara Arabs of the Sudan Belt,” Nomadic Peoples, vol.4, no.1, (2000), pp.37-49.

Ian Cunnison, The Baggara Arabs: Power and the Lineage in a Sudanese Nomad Tribe. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1966.

Yusuf Fadl Hasan, The Arabs and the Sudan from the Seventh to the Early Sixteenth Century. Khartoum University Press, 1973.

H.A. MacMichael, A History of the Arabs in the Sudan and Some Account of the People who Preceded them and of the Tribes Inhabiting Darfur (Volumes 1 and 2). Martino Publishing, Mansfield Center, CT.2005.

Stefano Manfredi and Caroline Roset, “Towards a Dialect History of the Baggara Belt” Languages 6, no. 3 (2021): 146.

St. John Bayle, Travels of an Arab Merchant in Sudan: The Black Kingdoms of Central Africa, Darfur, Wadai. Kessinger Publishing, 2010.

Al-Jazeera, “Sudan’s Feared Paramilitary Leader Signals Ambition to Rule the Country,” January 2, 2024.

And regular reporting from: