“The man who doesn’t ask his country for even a handful of earth for his grave deserves to be heard, and not only to be heard, but to be believed.”

—Augusto C. Sandino, “The Sandino Manifesto”

On July 1, 1927, the Nicaraguan revolutionary leader Augusto Nicolás Calderón de Sandino, a.k.a. Augusto “César” Sandino, proclaimed his manifesto extolling continued Nicaraguan resistance against U.S. intervention in his country.

The manifesto, supposedly written from the San Albino Mine in the mountainous Segovia region that borders Honduras, was a stirring nationalist document. In it, he rejected the loss of Nicaragua’s right to self-determination and called for the unification of Nicaraguans, Central Americans, and the “Indo-Hispanic race” in a collective struggle against “Yankee” imperialism.

Sandino’s plan was also firmly internationalist in its scope and effect, for his actions in defense of Latin American self-determination would go on to influence a host of regional and global revolutionary movements over the course of the 20th century.

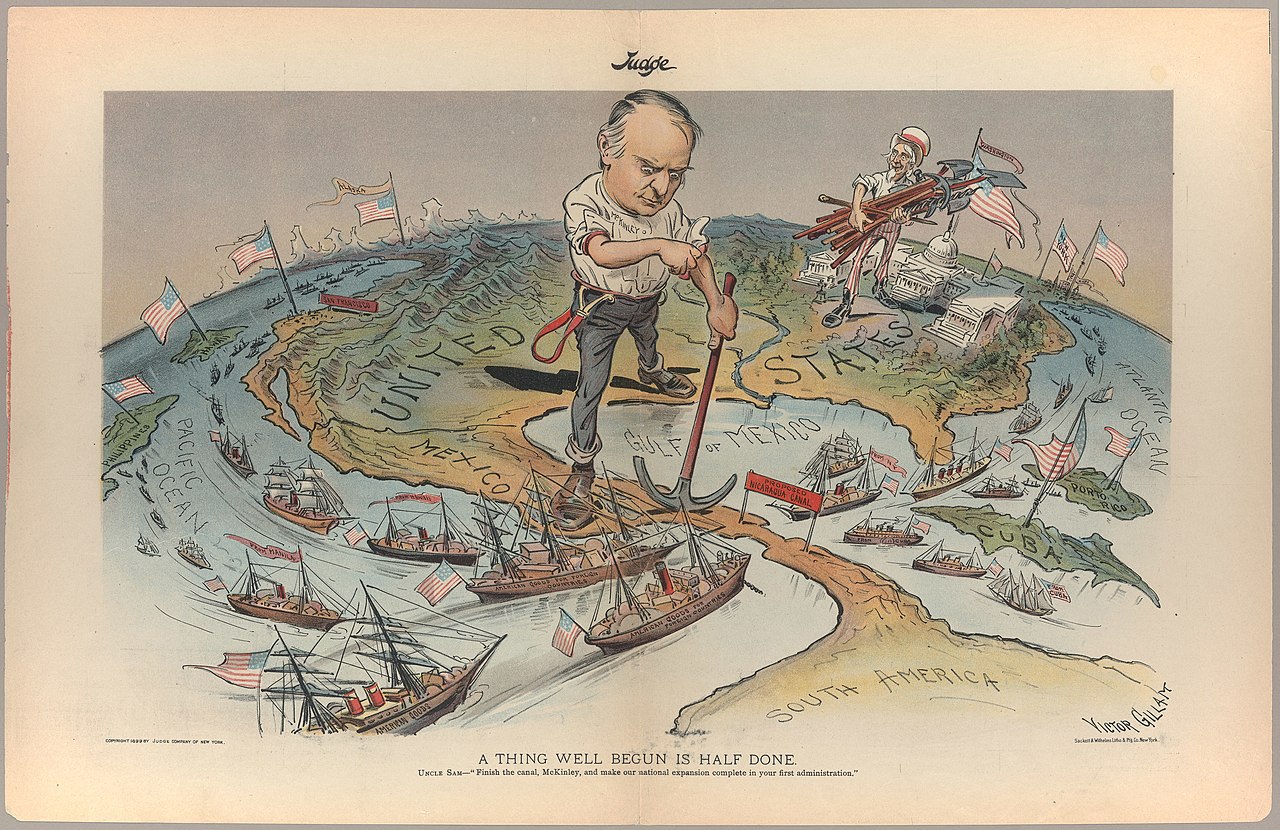

He articulated his revolutionary vision at a crucial point in Nicaragua’s history. Since the late 19th century, Central American and Caribbean countries had experienced increasing U.S. military, economic, and political intervention in their internal affairs.

This period of “neocolonialism,” stretching from 1880 to the early 1930s, was defined by “banana republics” and “gunboat diplomacy.” Essentially, U.S.-based corporations, most infamously the United Fruit Company, used bribery and other methods to gain the support of local governments.

If political leaders did not acquiesce to U.S. economic interests, their shores and harbors would be visited by U.S. warships carrying legions of hated Marines who would then work to install governments more amicable to U.S. business interests.

In 1898, for instance, with the advent of the Spanish-American War, U.S. military forces occupied Cuba, whose internal politics, economics, and foreign relations they would largely dictate for the next half-century.

When the pattern continued in Panama’s war for independence (1903), it had particularly disastrous consequences for Nicaragua. As naval warships prepared the way for Panamanian autonomy from Colombia and the construction of the U.S.-operated Panama Canal, hopes quickly faded for the planned Nicaragua Canal and all the revenue and investment such a commercial hub would have generated.

Then, in 1909, following Liberal president José Santos Zelaya’s attempts to both revive the failed canal and limit U.S. domination of Nicaragua’s economy, the U.S. sent its navy to the country and worked alongside Conservative leaders Emiliano Chamorro and Adolfo Díaz to install a U.S.-friendly government. It was this coalition of Conservative rulers who would go on to support the U.S. military occupation that lasted from 1912-1933 and to rule the country on and off until 1928.

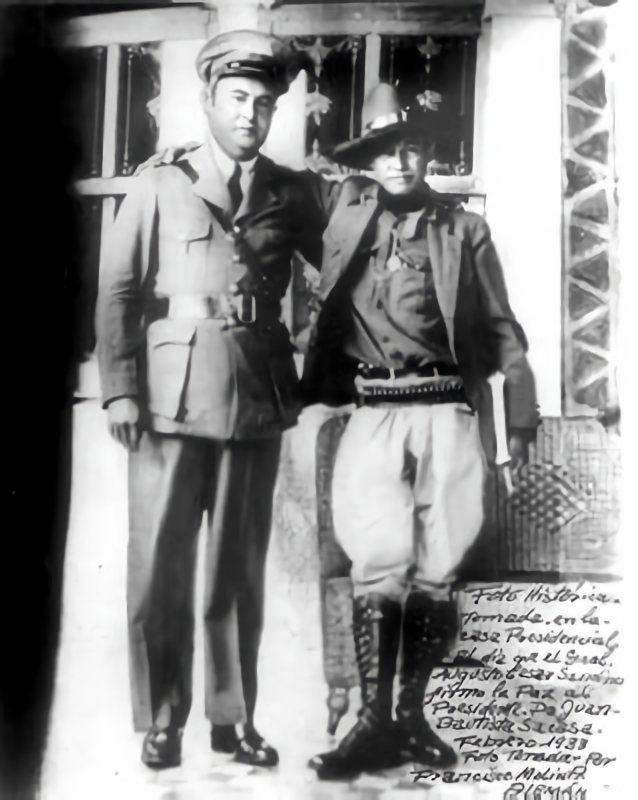

Liberal resistance to the U.S. occupation and the loss of Nicaragua’s democratic conventions boiled over into a civil war that lasted from 1921 to 1927. The movement involved both Liberal leaders—including future presidents José María Moncada and Juan Bautista Sacasa, as well as Augusto César Sandino himself—and Conservative factions who wished to end American hegemony over the Nicaraguan economy.

This broad coalition also included dispossessed members of the lower-class (rural campesinos, migrant workers, miners, and seasonal laborers) and those members of the middle and upper classes (like ranchers, merchants, urban professionals, and politicians) who believed in their country’s right to self-rule, free from foreign influence.

By 1927, after years of grinding conflict, Sandino remained the only revolutionary still opposed to U.S. occupation. Over the next six years, his forces engaged in a military campaign that mobilized Segovia’s peasantry into a classic example of rural-based guerrilla warfare.

While Sandino’s rebels would ultimately fail in their goal of achieving nationally-recognized autonomous rule within Segovia, their continued resistance succeeded in forcing the removal of the U.S. Marines from Nicaragua in 1933, (temporarily) signaling the prospect of a Nicaragua free from foreign domination.

These hopes were dashed a year later when the Nicaraguan National Guard assassinated Sandino on February 21, 1934. The Guard, a national military force trained by U.S. Marines, played a crucial role in bringing Anastasio Somoza García to power in 1936 and maintaining the Somoza family dynasty’s rule over the following four-and-a-half decades.

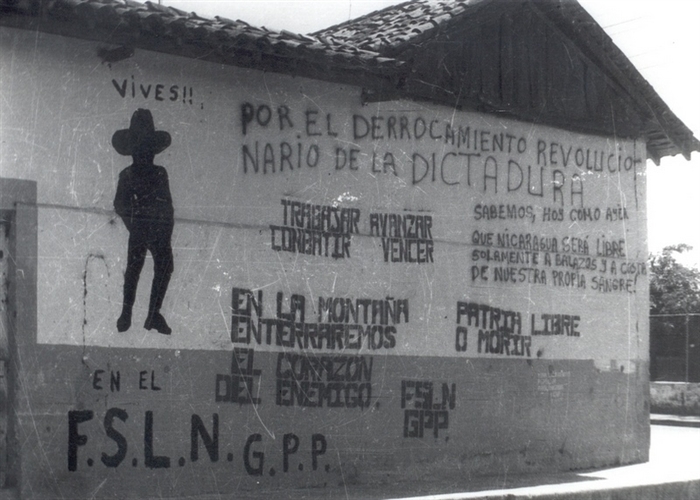

Nevertheless, despite the dashed short-term hopes of a truly democratic and independent Nicaragua, Sandino’s defense of national self-determination and development of guerrilla warfare tactics would go on to inspire revolutionary movements across the globe in the coming decades, especially the Cuban Revolution and Nicaragua’s own Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN).

The FSLN grew from a small-scale rebellion involving only a few dozen members in the early 1960s to an internationally-supported movement by the late 1970s. They took up Sandino’s legacy of paramilitary warfare and grassroots appeal to the rural poor disaffected by Nicaragua’s oligarchy and then injected their own elements of mass-based urban insurgency and a leftist Christian ideology inspired by liberation theology.

The FSLN succeeded in overthrowing the government of Anastasio Somoza Debayle in 1979, and its leadership, most notably President Daniel Ortega and Vice President Sergio Ramírez, led the country over the next decade.

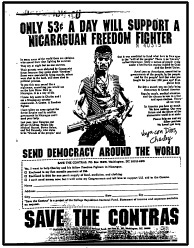

They furthered Sandino’s legacy through reforms directed towards improving national literacy rates, supporting peasant and urban proletariat collectives, and enhancing international bonds, as seen with the U.S.-Nicaraguan Solidarity Movement that emerged in response to the military and financial support the Reagan administration extended towards the anti-Sandinista “Contras.”

The decade-long conflict between the FSLN-dominated national government and the counterrevolutionary Contras sapped much of the early potential for socio-economic change. This failure to address the nation’s pressing issues of wealth and resource inequality, along with the implementation of IMF-supported austerity measures in 1987, ultimately led to the election of opposition candidate Violeta Chamorro and the ousting of the FSLN-led government in 1990.

Ortega and the FSLN party returned to power in 2006, but Sandino’s ideals did not. Ortega, alongside his vice-president wife Rosario Murillo, have worked aggressively to restrict citizens’ rights. Beginning in 2018, government forces and paramilitary thugs have violently cracked down on demonstrators, leading to the hospitalizations of thousands and deaths estimated in the hundreds.

Sandino’s vision for a more democratic Nicaraguan society remains unfinished. The current Sandinista party, dominated by an Ortega bent on creating a single-person or potentially single-family dictatorship, exhibits eerie similarities to the Somoza dictatorship that the FSLN and the revolutionary movement of the 1970s worked so hard to overthrow.

Nevertheless, Sandino’s popular legacy as a Nicaraguan and international symbol of anti-imperial resistance and national self-determination lives on.

![]()

Learn More:

Babb, Florence E. “After the Revolution: Neoliberal Policy and Gender in Nicaragua.” Latin American Perspectives 23, no. 1, Winter, 1996. Pp. 27-48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2633936.

Bendaña, Alejandro. “The Rise and Fall of the FSLN.” NACLA Report on the Americas 37,

Dospital, Michelle. Siempre más allá…: El movimiento sandinista 1927-1934. Mexico: Centro de estudios mexicanos y centroamericanos, 1996

Fagen, Richard R. The Nicaraguan Revolution: A Personal Report. Washington, D.C.: The Institute for Policy Studies, 1981.

Finzer, Erin S. “Modern Women Intellectuals and the Sandino Rebellion: Carmen Sobalvarro and Aura Rostand.” Latin American Research Review 56, no. 2, 2021. Pp. 457–471. https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.878.

Perla, Héctor Jr. “Heirs of Sandino: The Nicaraguan Revolution and the U.S.-Nicaragua Solidarity Movement.” Latin American Perspectives 36, no. 6, November 2009. Pp. 88-100. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20684687.

Ramírez, Sergio. El pensamiento vivo de Sandino. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Universitaria Centroamericana, 1974.

Sierakowski, Robert J. Sandinistas: A Moral History. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2020.

Walker, Thomas W., ed. Revolution & Counterrevolution in Nicaragua. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1991.

Walters, Jonah. “Remembering Sandino.” Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2017/03/augusto-sandino-nicaragua-somoza-us-imperialism-sandinista.