On November 8, 1942, American and British forces invaded beaches and ports across French North Africa. Officially opening a long-awaited second front against the Axis, operation Torch constituted the biggest and most complex amphibious landing to that point in world history.

The path to Northwest Africa, however, was never a foregone conclusion. America’s commitment to the Allied war effort after Pearl Harbor brought relief to many British military leaders, but with it came the lingering questions of when, where, and how their combined forces would engage German forces in the west?

Months of prolonged—often acrimonious—debate followed. Thrashing out the particulars in a six-week “transatlantic essay contest,” by July 1942, Anglo-American leaders agreed to invade Vichy French North Africa by year’s end.

Hoping to give French soldiers an opportunity to cooperate with the Allies and relieve pressure on British armies fighting in Egypt, American domestic pressure, British strategic interests in the Mediterranean, and Soviet pleas to open a second front also played a major role in the decision.

The affair was steeped in uncertainty from the start. Participating troops were inexperienced and did not speak the local languages. Hundreds of miles of treacherous terrain separated the invasion’s three proposed landing sites in Morocco and Algeria. Stormy winter forecasts portended difficult if not dangerous seaborne operations. Shipping limitations and the ongoing U-Boat menace vexed Allied planners. Above all, nobody knew how Vichy French troops would respond.

On July 26, 1942, American Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Allied Commander over the operation. As the head of an Allied force, Eisenhower strove to inculcate ideals of Anglo-American harmony in his team. Disagreements nevertheless abounded.

After assembling a small integrated staff of British and American officers at Norfolk House in London, planning began in earnest. They had 74 days to plan and 30 days from the issuance of orders to execute the operation.

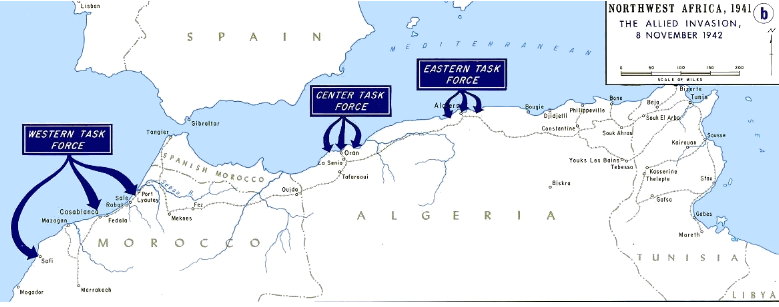

The undertaking required a herculean logistical effort. Three independent armadas—two dispatched from England, one from the United States—would secretly traverse thousands of miles of contested Atlantic waters and simultaneously land their troops at three disparate landing sites near Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers.

Following the landings, Eisenhower’s forces would strike east in a bid to occupy Tunisia before it could be reinforced by German and Italian forces. More than 500 miles from Algiers, the drive to Tunis necessitated its own complex support effort contingent on the success of the amphibious landings.

Allied planners tried to engineer favorable local conditions for the assault forces. Painstakingly assembled over the preceding years, a diverse underground network of Franco-American civilian and military personnel led by American diplomat Robert Murphy gathered intelligence, identified local collaborators, and made plans to sabotage defenses ashore.

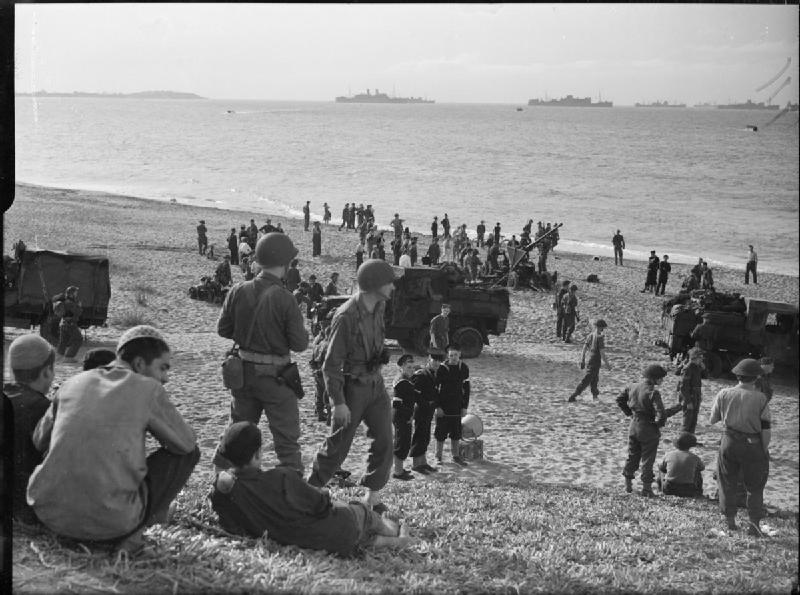

Around midnight on November 8, all three task forces reached their jump-off points and prepared to send their forces ashore. Privately, Allied leaders marveled at their luck; to have transported history’s largest amphibious armada–some 670 vessels and 107,000 soldiers in total–across the Atlantic almost wholly undetected seemed impossible given Torch’s complexity and scale.

“The entire operation,” according to journalist Wes Gallagher, “was carried out with the delicate synchronization of an expensive watch.”

Still, not everything went to plan. Having flown 1,500-miles from England in the first–and furthest–airborne operation in American history, just six of 39 C-47 troop carrier planes managed to drop their paratroopers; the rest became disoriented by thick clouds and unfamiliar terrain. At sea, heavy waters and strong currents plunged carefully planned timetables into chaos.

The Allies persevered.

Landing on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, American ground, naval, and air forces met stiff resistance. Covered by intact shore batteries, French naval forces sortied and initiated “the largest surface, air, and subsurface naval action fought in the Atlantic Ocean during World War II.” After three days of fighting, General George S. Patton’s 39,000 American forces enveloped Casablanca and forced the garrison to surrender.

Further east, the Allies met weaker resistance. Though French defenders repulsed a British attempt to force entry into Oran’s heavily-defended harbor and the airborne operation was mostly inconsequential, Oran’s defenses quickly capitulated.

The Algiers landings exhibited the closest cooperation between Anglo-American forces. Assaulting beaches east and west of the capital while a third force staged a frontal assault on the harbor, the Allies benefitted from chaos sewn by the French underground, overcoming early delays and confusion as they secured a local cease-fire by the end of the first day.

The invasion succeeded in bringing French North African forces back into the Allied fold. After signing an armistice on November 11, 1942, the Allies secured Morocco and Algeria at a cost of just over 2,000 casualties. From then on, French soldiers would fight arm-in-arm with British and American forces through the remainder of the war.

Torch coincided with stunning victories at El Alamein and Stalingrad. Sensing improving Allied fortunes after years of setback and tragedy, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill summarized the operation’s significance at a speech in London two days after the landings: “Now this is not the end,” he said. “It is not even the beginning to the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

Like most operations in the Mediterranean, Torch has faded from popular memory. Overshadowed by Normandy and the subsequent campaign through Northwestern Europe, it is often characterized as the beginning of a long, grinding journey through the Mediterranean–a costly sideshow of limited strategic value.

It was, nevertheless, a watershed moment and precedent setter. As the debut of American forces in the west and the war’s first combined and joint enterprise featuring troops from multiple nations landing by sea and air, Torch illustrated the vitality of the Anglo-American partnership, the strength of Allied industry, and the coalition’s latent ability to turn enemies into allies.

Many wondered then–and since–whether the Allied odyssey through Northwest Africa was necessary. While a premature invasion of Northwest Europe would have been impractical and risky, Torch offered an acceptable middle ground for allies with conflicting strategic agendas–a “springboard to Berlin” that enabled newly-minted allies to gain vital experience they would sorely need when they reentered the European continent just nine months later.