Smallpox is a deadly, viral disease that can be traced back at least to the time of the pharaohs. It played a historic role as the disease for which the first vaccine was developed (in 1796); and it was a disease that was responsible for as many as 300 million deaths in the 20th century alone.

On May 8, 1980, smallpox played another momentous role in the history of public health, when the World Health Organization officially declared the disease eradicated. This was the first and only time in human history that a deadly human disease was eradicated (rinderpest, a cattle disease was eradicated in 2011; polio is teetering on the edge).

The eradication of smallpox broke what World Health Organization physician Donald Henderson (the architect behind the smallpox eradication program) has described as at least a 3,500-year chain of infections. This immense public health success was the result, among other factors, of the incredible power of vaccination.

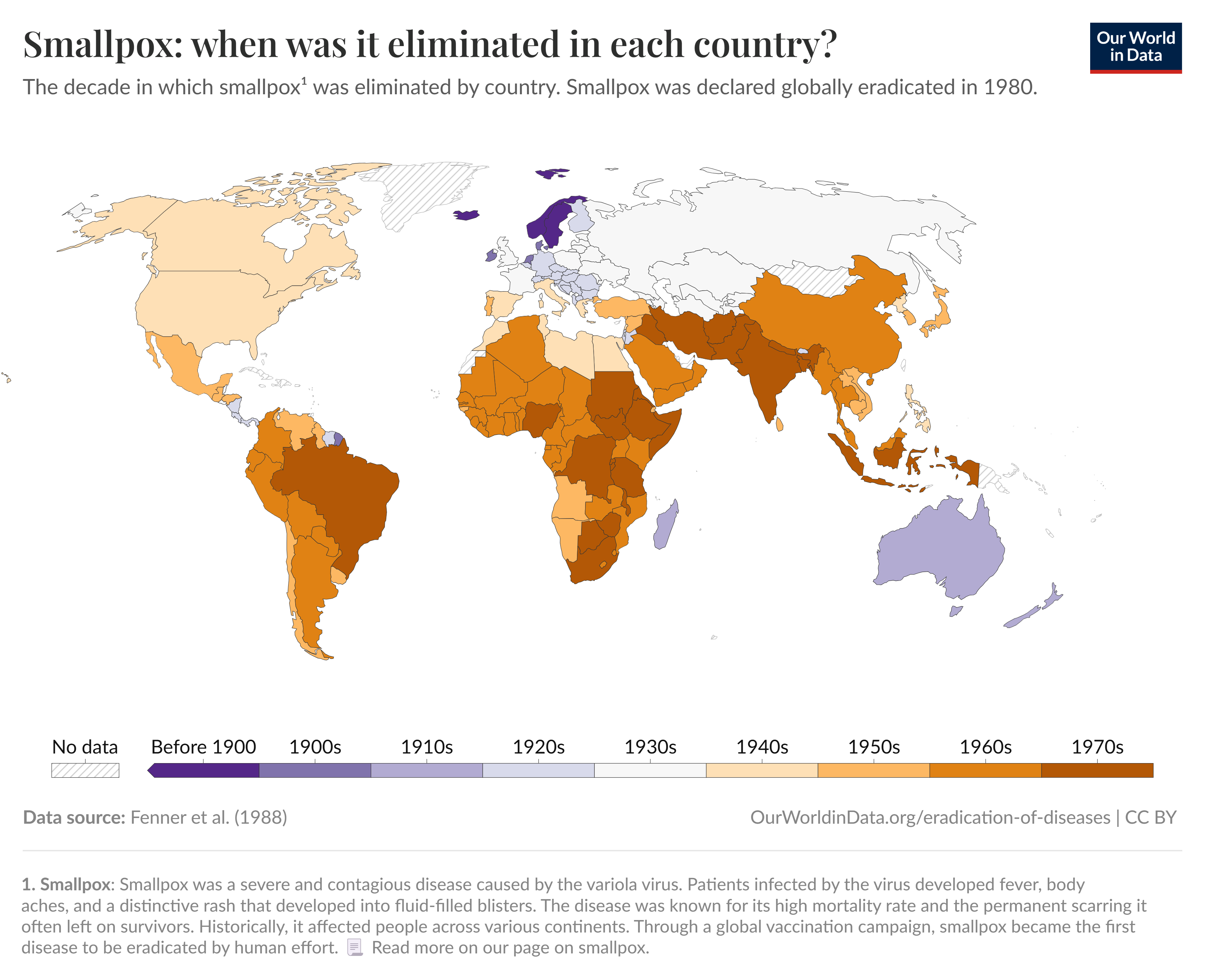

But breaking this 3,500-year chain of disease did not happen suddenly in 1980, nor solely because of vaccines. Smallpox eradication was the result of a decades-long global program involving complex geopolitical cooperation, human ingenuity, and technological innovation beginning in the 1950s.

Through widespread vaccination campaigns, smallpox was in decline throughout much of the Global North by the end of the Second World War. The last outbreak in North America occurred in 1947, when a traveling merchant from Mexico brought the disease back to New York City.

But a disease that existed anywhere could exist everywhere, inspiring Dr. Brock Chisholm, the Canadian Director-General of the World Health Organization, to offer a bold proposal in 1953: to undertake a worldwide program for smallpox eradication. His colleagues demurred. The proposal was tabled twice before being dropped entirely in 1955 in favor of an effort to target malaria.

In 1959, however, Deputy Minister of the Soviet Union, Viktor Zhdanov, renewed the proposal. Zhdanov proposed a five-year program to “practically” eradicate smallpox. His plan called upon the WHO to establish the program and provide the funding for national biologics firms to develop sufficient vaccine stocks, and to train local vaccinators around the world in regions where smallpox was still endemic.

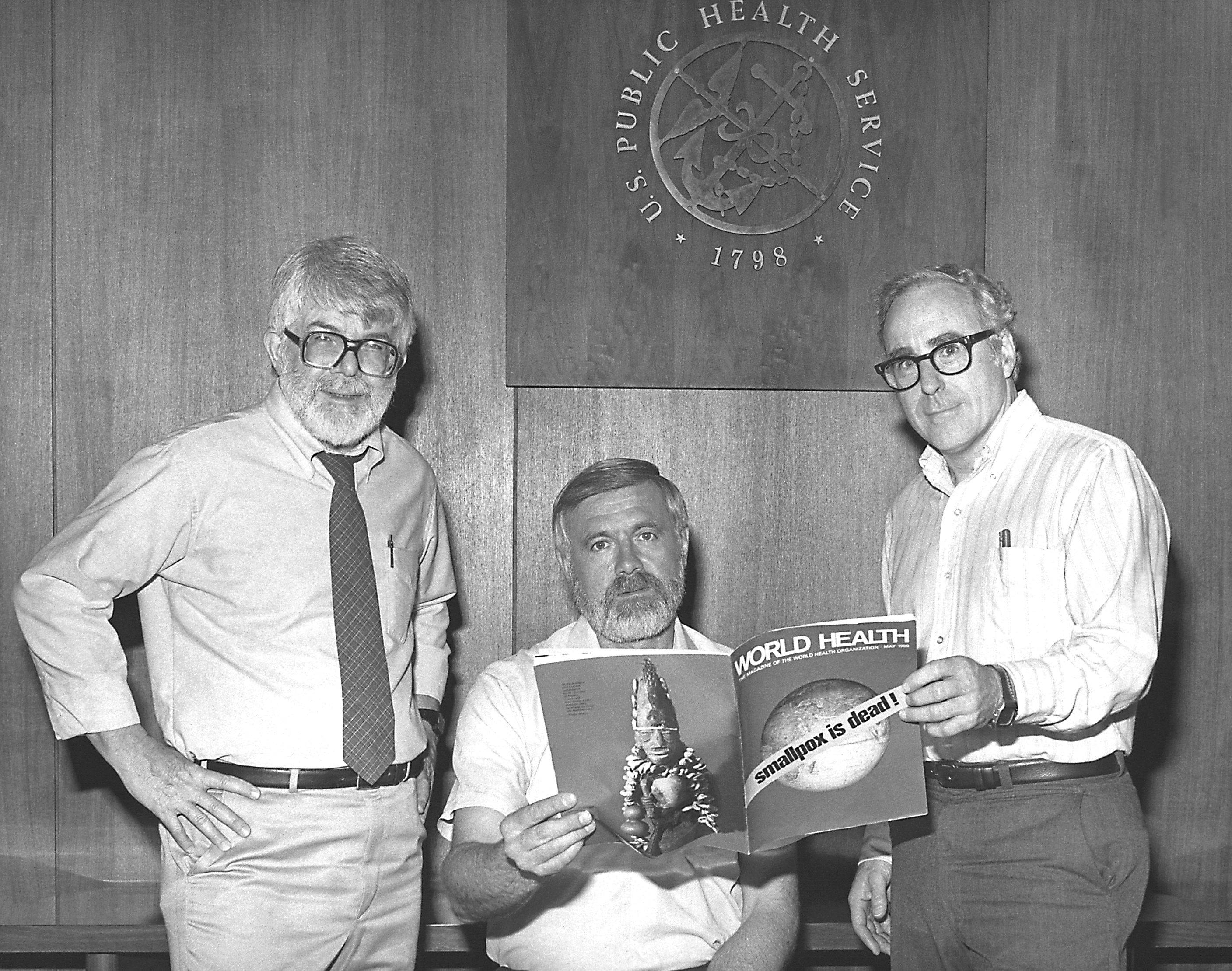

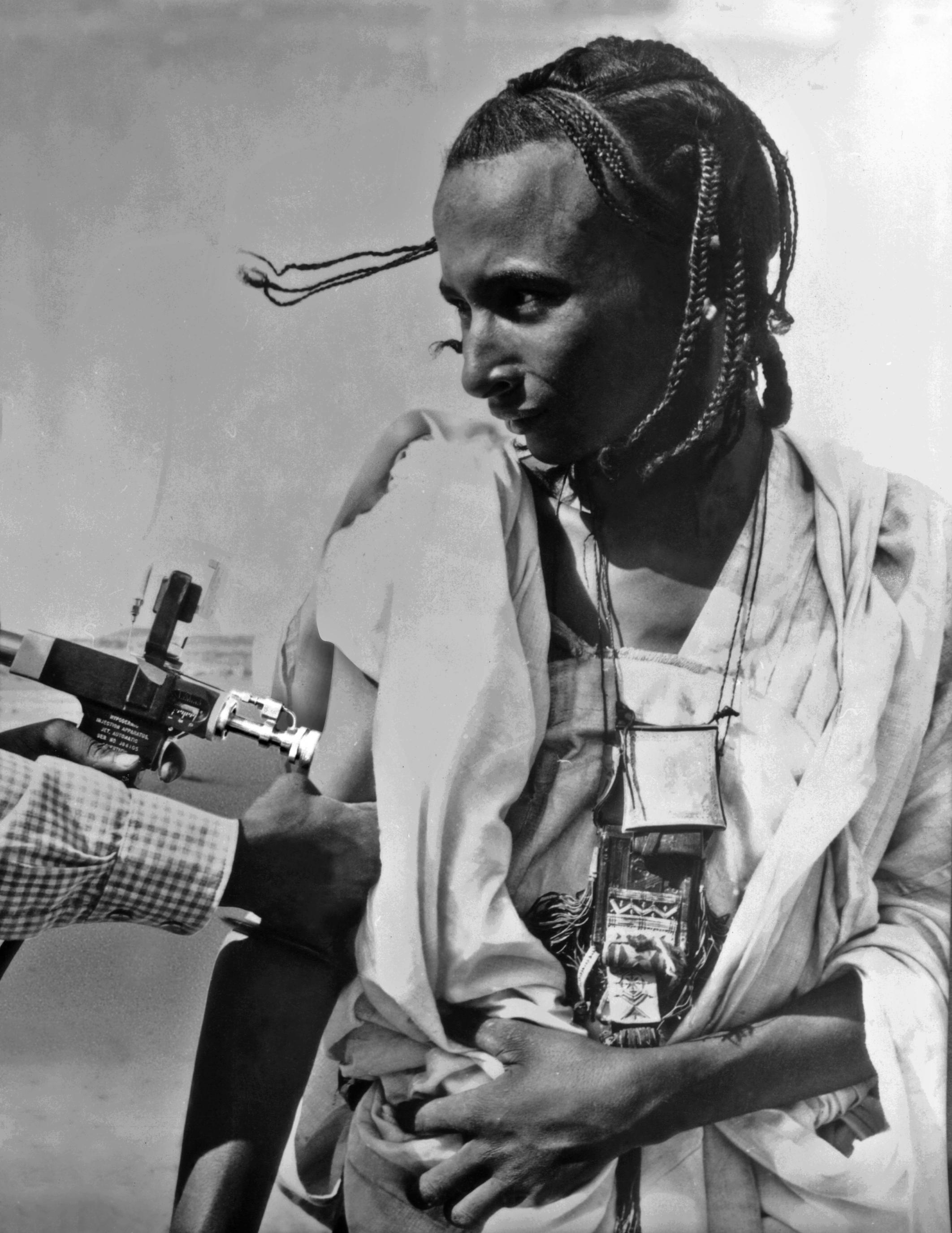

Zhdanov’s program was a partial success. New technologies like the bifurcated needle and jet injectors stretched vaccine supplies. In 1965, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson expanded America’s support for the technical and financial aspects of the program in western and central Africa. He also appointed Henderson, then head of the Surveillance Section of the CDC, to head the program. But the WHO budget for the program remained limited to around $100,000 per year.

Between 1959 and 1966, the percentage of the global population living in smallpox-endemic regions was nearly cut in half from 59 percent to 31 percent. But this was far from Zhdanov’s promise of eradication in five years.

The World Health Organization went back to the drawing board, reconceptualizing how to expand eradication. Fighting to increase limited budgets, and even against opposition from the new WHO Director-General, the intensified smallpox eradication program passed by only two votes.

Henderson described the new plan as “a universal effort unlike any that had ever been undertaken” before. More than 50 nations contributed. Despite the divisions of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union worked together towards a common purpose: combating smallpox in 43 countries with a combined population of over 1 billion people.

The new program sought to reach >80% vaccination rates in smallpox-endemic countries to reach a community-immunity threshold, followed by a fast-acting system of surveillance-containment developed by American epidemiologist William Foege.

Following organized mass vaccination efforts, local teams would be sent out to small-endemic regions to check for lingering cases and then vaccinate those patients and those immediately in contact with them to create a “ring” of vaccination around the virus to stop its spread. Of course, this system also had to be adaptable to diverse national political and cultural realities.

As these rings of vaccination around the virus tightened, more and more countries became smallpox-free. But in some, especially rural regions, smallpox lingered well into the 1970s.

In India and Bangladesh, for example, with a combined population of over 700 million people, many of whom lived in rural regions or were frequent commuters, surveillance-containment proved especially difficult. Refugees from civil war, famine, and floods were hard to reach.

Among these refugees, Rahima Banu, a three-year-old girl living on Bhola Island, in the Barisal district of Bangladesh, became officially the last person to become naturally infected with the more deadly strain of smallpox (variola major).

Henderson and his team heard reports of her illness on October 16, 1975. They traced her contacts and poured vaccines and vaccinators into the region to block any spread.

Meanwhile, the WHO was still working to eradicate the milder strain of the disease, variola minor, in parts of the Horn of Africa. Last among these was Ali Maalin, the final person to naturally contract smallpox in the world. Maalin was a hospital cook in Merca, in southern Somalia, who was also a part-time vaccinator, though he personally was not vaccinated.

Roughly a decade after the launch of the intensified eradication program, on October 12, 1977, Maalin guided a group of children infected with smallpox to an isolation camp for vaccination and treatment, but the WHO investigators failed to include him when contact-tracing the children.

Ten days later, on October 22, Maalin fell ill with a fever and a headache. He was treated for malaria. Four days after that, his rash appeared, but because he was presumed vaccinated, he was diagnosed with chickenpox and was discharged from the hospital.

Only later in the month did his colleagues realize Maalin had variola minor, the milder strain of smallpox. He was eventually put in isolation and fully recovered by the end of November. Meanwhile, the WHO administered 55,000 vaccinations, beginning among a network of 90 contacts.

The region was monitored for smallpox for months. There were no cases. This was the end.

Henderson has described Maalin’s experience as an example of “omissions and mistakes in program operations.” Luckily, despite avoiding isolation, Maalin did not further spread the virus. His was the final natural case of this ancient, deadly disease in the world.

Tragically, however, the last fatality from smallpox followed in their wake: Janet Parker, a medical photographer at the University of Birmingham (UK) Medical School.

Despite being vaccinated in 1966, a laboratory leak in the floor below her workspace resulted in Parker’s exposure to smallpox in a most unnatural way. She was taken to the East Birmingham Hospital, where she was diagnosed with variola major on August 20; she died on September 11 and became smallpox’s final victim.

In the years that followed the isolation of Banu and Maalin and the death of Janet Parker, the WHO continued to monitor for any remaining cases of smallpox in even the most remote parts of the world. The organization had to be sure there were no lingering cases. It found none.

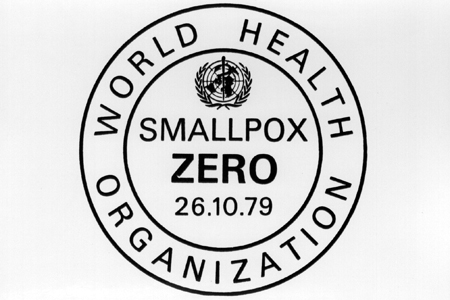

On October 26, 1979, two years to the day after Maalin’s rash first appeared, the World Health Organization finally offered a recommendation that smallpox was officially eradicated.

It would take some time for the recommendation to work its way through the World Health Assembly. But, on May 8, 1980, it formally accepted the WHO’s recommendation that smallpox was eradicated.

Officially and for the first time ever, the World Health Organization declared the world completely free of one of the deadliest infectious diseases in human history.

![]()

Learn more:

Ian Glynn and Jenifer Glynn, The Life and Death of Smallpox (Penguin, 2005)

Donald Henderson, Smallpox: The Death of a Disease: The Inside Story of Eradicating a Worldwide Killer (Prometheus, 2009)