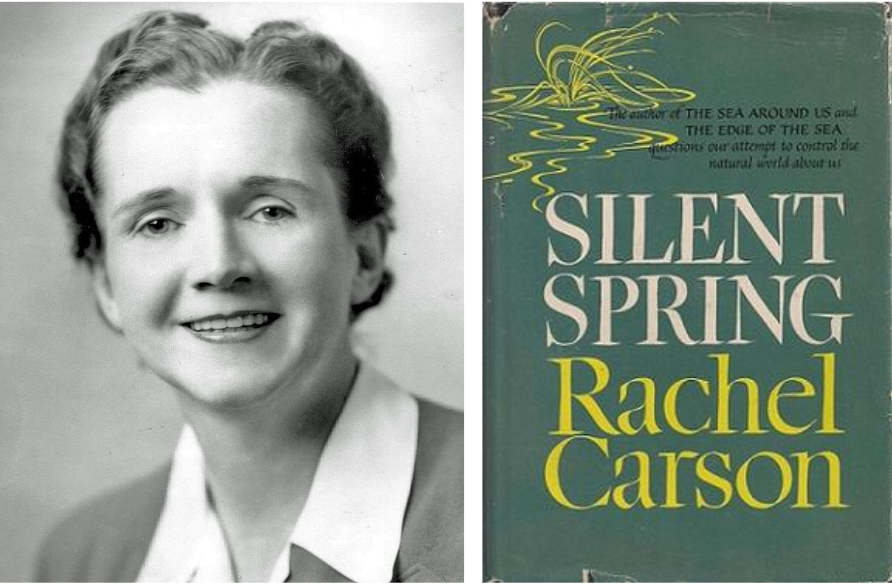

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring shocked the American public when it was published in the summer of 1962. Carson hooked readers by describing a fictional town where spring no longer marked the singing of birds, the buzzing of bees, or the laughter of children.

Instead, Carson’s “Fable for Tomorrow”—extrapolated from four years of research—warned how excessive pesticide use ravaged birds, annihilated bees, and sickened the town’s inhabitants. Carson revealed to readers how pesticides, including suspected carcinogens, indiscriminately killed insects and plants, while also accumulating in water, soil, and the bodies of fish, birds, and people.

Rachel Carson devoted her life to the study of the natural world after falling in love with the landscapes surrounding her childhood home of Springdale, Pennsylvania. She studied marine biology and graduated with an MA in Zoology from John Hopkins University in 1932.

A trailblazing female scientist, Carson became editor-in-chief for all U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service publications in 1939 and wrote popular books on ocean life. These works illustrated the connections between organisms and their environment. The theme of interconnectedness influenced her later work on pesticides.

Silent Spring adeptly critiqued the American chemical industry and federal regulation of toxic chemicals at a time when many people’s faith in them was nearly unshakeable. She did so by placing humans within the web of ecology, rather than outside it.

This move challenged long-held notions that science allowed humans to control—and thereby live apart from—nature. Carson asked readers, “whether any civilization can wage relentless war on life without destroying itself,” because humans were inherently reliant on other organisms for their own survival.

The chemicals that Carson questioned—DDT, 2,4-D, Heptachlor, among others—gained widespread acceptance during and immediately after World War II. During the war, DDT—first used for pest control in 1939—was seen as a miraculous chemical that killed mosquitos and lice, saving American GIs from malaria and typhus.

This endeared pesticides to the American public who saw them as tools that could save lives and feed hungry mouths. It would not take long, however, before some began to sound the alarm on chemical over-use.

While the public, USDA, chemical companies, and farmers embraced pesticides with a fervor one historian has compared to a love story, a growing number of scientific studies in the 1940s and 1950s demonstrated the insidious harm stemming from excessive pesticide use.

In 1944, Hugh E. Morrison, an entomologist at Oregon State University, observed DDT residue persisted on washed fruits and vegetables and noted “the safety factor of DDT to man has not been clearly established.” Additionally, scientists in Michigan noted that DDT used to combat Dutch Elm Disease in the 1950s wiped out native robin populations who fed on worms suffused with the chemical.

Carson’s magic as a writer was to connect these scientific studies and transform them into a compelling narrative that captured public attention.

Silent Spring became one of the twentieth century’s most significant works of nonfiction. Carson’s gripping prose and spirited defense of her research in the face of vicious personal attacks by the powerful chemical industry are credited with inspiring a surge of American environmental activism, the creation of the EPA in 1970, and the banning of DDT in 1972. Tragically, Carson, who died of breast cancer in 1964, did not live to see these developments.

Despite some gains in protecting environments and human health from toxic substances, the United States failed to learn Silent Spring’s lesson of applying the precautionary principle to toxic chemicals.

Pesticide use in the U.S. has continued to grow since Silent Spring. In 1960, the U.S. used 196 million pounds of pesticides, 631 million pounds in 1981, and an estimated 1 billion pounds in 2017.

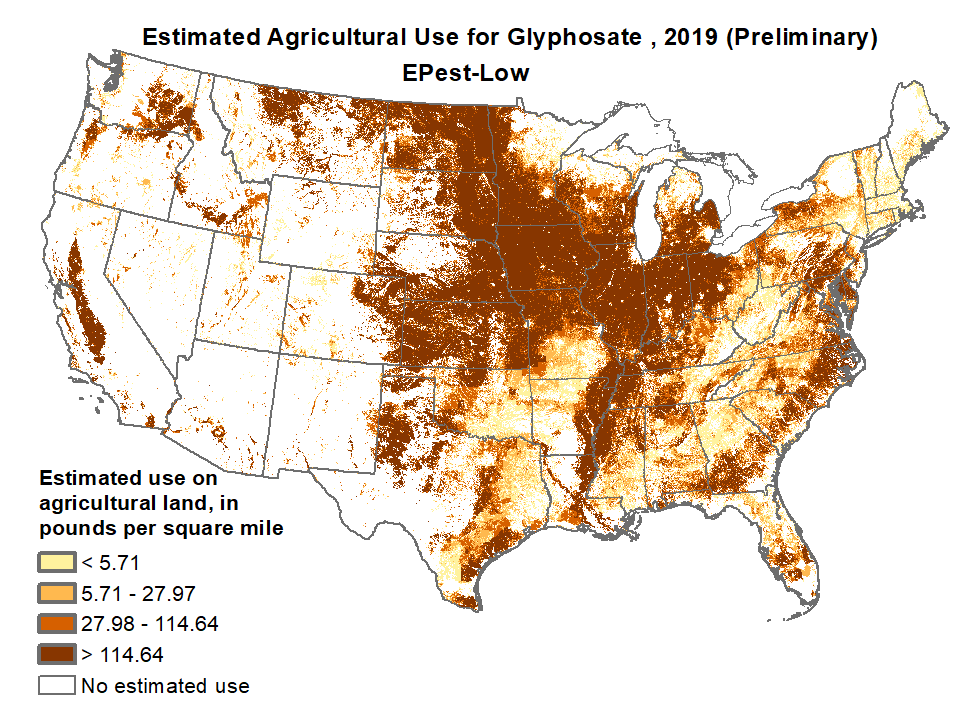

After Silent Spring, the debate over pesticides shifted from discussing their safety in general to deliberating the safety of specific chemicals. For example, regulators determined DDT harmed humans and animals, but approved other pesticides like glyphosate, which they considered safe. This shift in perspective encouraged the continued use of pesticides in unprecedented quantities. Yet many of the supposed “safe” pesticides are proving to be anything but.

Monsanto, a leading American chemical manufacturer, released its blockbuster herbicide Roundup (active ingredient glyphosate) in 1974. Regulators considered glyphosate safe for humans and it proved highly effective when paired with Roundup ready corn and soybeans in the 2000s. As a result, so much glyphosate is used each year that traces of it can be found in a cornucopia of food products ranging from Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream to beer and wine.

Yet, studies link glyphosate exposure to cancer and recent court cases have revealed Monsanto’s role in influencing federal regulators’ decisions on glyphosate. The German chemical giant Bayer purchased Monsanto in 2018 and set aside over $4.5 billion to settle Roundup cancer claims. Some estimate the fallout over Roundup could cost the firm $16 billion.

Furthermore, over-use of pesticides fosters resistance in plants and animals, resulting in a demand for an ever more diverse array of chemicals, many more potent than glyphosate. As of 2021, over 48 species of weeds have developed “Roundup resistance.”

Carson warned us about these issues— contaminated food, aggressive cancers, and super weeds—in Silent Spring.

While the situation sounds depressing, there are reasons to remain optimistic. Organic farming, for example, has exploded in the United States. Between 2011 and 2016 the number of organic farms and the sale of organic foods in the U.S. doubled and nearly 5 million acres of farmland are certified organic. This only accounts for one percent of U.S. farm acreage, but the rapid growth is a step in the right direction. Additionally, new research in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strives to develop biological methods of pest control in conjunction with chemicals.

People are also working to hold powerful companies like Bayer to account using the legal system. In June 2022, the Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Bayer, forcing the company to pay Edwin Hardeman—a Californian who claimed Roundup gave him cancer—$25 million in damages.

And community organizations, like Californians for Pesticide Reform, are pushing for stricter regulation and more thorough study of pesticides used in the United States. These are all steps toward creating safer environments for humans, plants, and animals, but there is more work to be done.

We have yet to heed Rachel Carson’s warnings. Even decades later, Silent Spring still has much to teach us about living in a world drenched with pesticides. ![]()

Learn more:

Baek, Yousoon et al. “Evolution of Glyphosate-Resistant Weeds.” Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology vol. 255 (2021): 93-128.

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. 50th anniversary edition. Boston: Mariner Books, 2012.

Daniel, Pete. Toxic Drift: Pesticides and Health in the Post-World War II South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Davis, Frederick Rowe. Banned: A History of Pesticides and the Science of Toxicology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Elmore, Bartow J. Seed Money: Monsanto’s Past and Our Food Future. New York: W.W. Norton, 2021.

Lear, Linda. Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. Boston: Mariner Books, 2009.

Mart, Michelle. Pesticides, A Love Story: America’s Enduring Embrace of Dangerous Chemicals. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015.

Nash, Linda. Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge. Berkley: University of California Press, 2006.

Russel, Edmund. War and Nature: Fighting Human and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Worster, Donald. Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas. 2nd Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.