There’s something special about learning how to ride a bike. Call it a rite of passage or just a childhood memory, that first ride without training wheels or without the assistance of a parent is unforgettable. When I was six years old, I distinctly remember falling off my bicycle when I was trying to do tricks and breaking my hand.

But our experiences are far from those of the earliest American cyclists - though they did tricks too. In his first book, Evan Friss argues that “there was an exceptional moment at the end of the nineteenth century in which bicycles shaped American cities and the lives of those who lived there.” (9) Drawing from sources across the nation – from New York to Chicago to San Francisco - The Cycling City presents a history of cyclists and how they shaped a place for themselves and their bikes in cities across the nation at the end of one of America’s most innovative centuries. The first half of the book focuses on the rise of cycling, who the cyclists were, and how they changed roads and cities. The second half elaborates further why certain groups of cyclists rode in the 1890s before cycling’s decline at the turn of the twentieth-century.

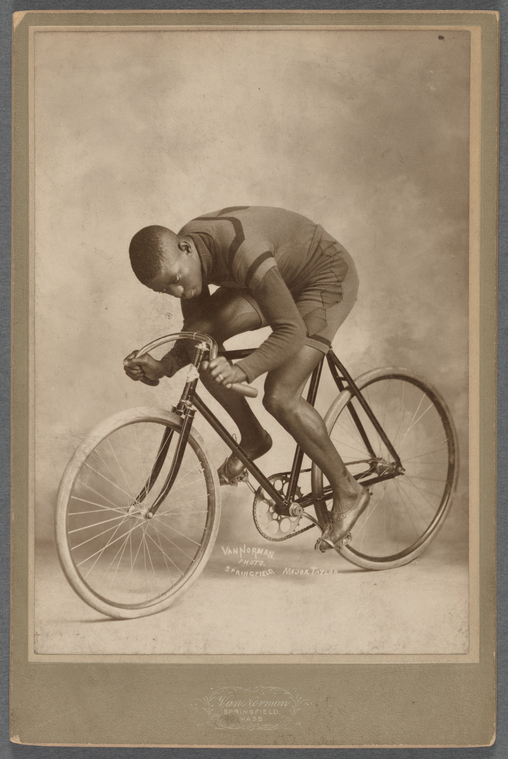

Rather than learning as children, helped along by parents on bicycles made for children, cyclists in the 1890s were taught in classrooms and were the people you might least expect to see on a bicycle today: middle-class, white, young men. There were other cyclists too, such as African Americans, Chinese, Polish, elite classes, and women, just to name a few, and each rode for any number of reasons. Newspapers and advertisers at the time offer a multitude of reasons why individuals would ride, but Friss relies heavily on private papers to delve into personal motivations, which ranged from independence to equality, from recreation to utility.

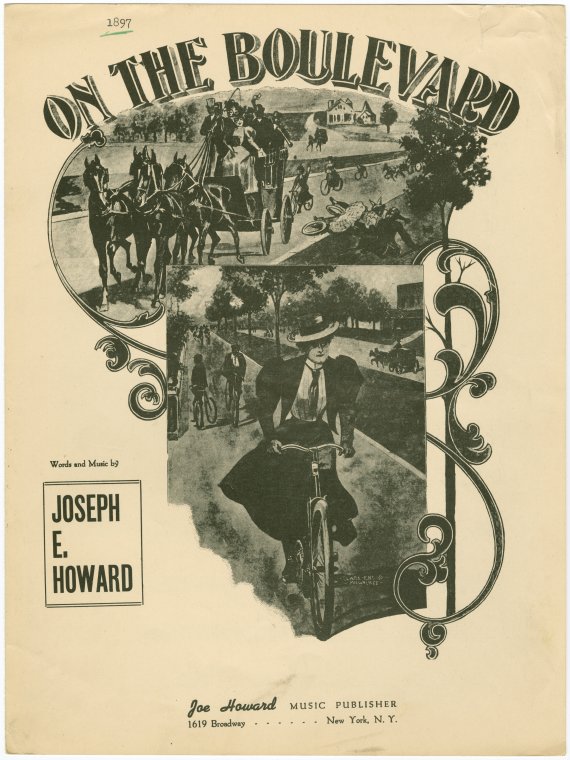

Middle-class businessmen and clerics rode to work, rode out of the city, and rode for recreation in the evenings. Cycles gave them freedom and some level of equality. With their newfound ability to leave the city during their free time or to ride leisurely at night, given that parks and paths were lit with electricity, the middle-class found themselves on more equal footing socially with the upper-class in the cities. Rather than being isolated to where they could trek to on foot or only where the streetcars and public transportation could carry them, bicycles allowed their riders freedom and independence, whether they rode out of necessity or utility was a question of personal preference.

On the other hand, wealthier cyclists thought of the bicycle as a tool for recreation and health. The earliest cyclists were elite, athletic, young men who had both the time and money to invest in cycling. But as they felt threatened by the widespread popularity of cycling, the elite created private cycling clubs that limited access to only the “right” type of cyclist through dues and entrance qualifications. Donning uniforms and organizing parties, cycling clubs were one type of group where cyclists could come together, but they were not merely for elites only.

|

|

The most interesting riders were the wheelwomen, whom Friss allots a whole chapter to discussing in detail. While joining men in their fight for position of cycles in the city, wheelwomen also used the bicycle for reform. Women of all classes and reasons found something attractive about the bicycle: sometimes as representative of emancipation and power, or independence and equality, or as what had gone wrong with young city women. Regardless of opinion, the public nature of women cycling (and even the clothes they wore while doing it) provided women with greater visibility. According to Friss, there is “no doubt” that the bicycle appeared to provide women with a revolutionary tool. (185)

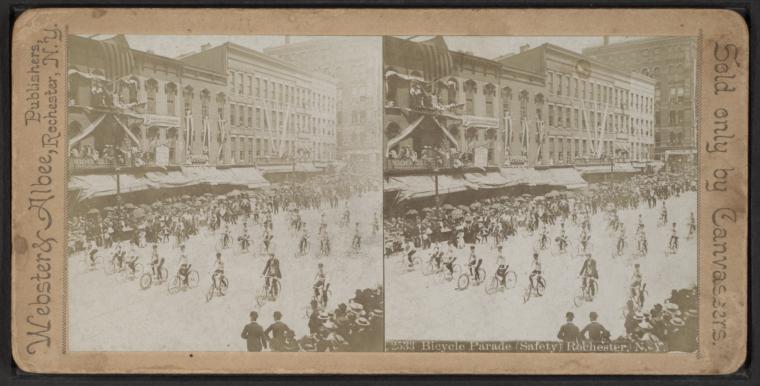

For every type of cyclist, there was a group that accommodated them and, though they disagreed over who should ride and why, they banded together to help define a place for the cycle in the city, cycling in parades for the ability to ride on the road, to not be banned from parks and paths, to be equal in status to other vehicles.

However, even as these disparate groups came together in celebrations of of cycling, the status of the cycle was challenged. Cyclists were not the only ones using the roads; streetcars, pedestrians, horses, and carriages all shared the road with this new, and quick, form of transportation. There were complaints of the recklessness of cyclists - fondly known as “scorchers” (think Premium Rush starring Joseph Gordon Levitt) - who were able to weave in and out of traffic, scaring horses and running over pedestrians, but cyclists had complaints as well. Streetcar tracks were difficult for bicycles to cross and road conditions in cities were poor. Cyclists were among the earliest advocates of improving road conditions in American cities.

|

| Groups of cyclists rode together advocating for their vehicles, for better road conditions, and for reform. In this image from Rochester, NY, cyclists joined together for bicycle safety. |

One of the great national debates on the status of cycles and their place in the city was in New York City’s Central Park, where in 1880 the Commissioners of Central Park outlawed cyclists from enjoying its rolling hills and shaded paths because the cycles scared the horses. Over the next few years, attempts were made by the cycling community to open Central Park to everyone. After efforts at the local and city level failed, the “bicycle vote” eyed the state government that, in 1887, passed the “Liberty Bill,” which garnered bicycles the legal status to use the road, but this was only the beginning. (70) It would not be long before the increase in cyclists, the traffic they created, and the competition for road space between cyclists, pedestrians, and streetcars prompted broader and longer lasting reforms.

Friss’s strongest and most persuasive arguments come when he discusses New York City and the East Coast. Many of the reforms and movements appeared to begin there and ripple out across the country, just the like bicycle itself did. While the inclusion of examples throughout the United States was useful in demonstrating how the “cycling city” was a national phenomenon, the addition of examples from other cities, particularly the small cities in Middle America like Kansas and Oklahoma, felt forced and repetitive.

Cycles were revolutionary, if only for a brief period of time. The rapid rise and just as rapid fall of cycles was unexpected but life changing to both those who rode them and those who didn’t in America’s cities. Though there were differences, the general trends were the same across the United States - the cycle came and changed the way Americans thought about roads, about transportation, and about what a city should be, or even would a city had the potential to be. Cycling utopias that were a thing of the past are now becoming ever more present in our current situation with pollution and traffic and global warming. Might cycling be the answer that we are looking for, just like in the 1890s? Although Friss concludes that, no, these cycling utopias are likely unobtainable, it should not keep us from looking to the past to “help us understand what might have been and what might come next.” (206) As bicycles now return to American cities, from Brooklyn to the Bay Area, Friss's book is a nice reminder that we've been here before.