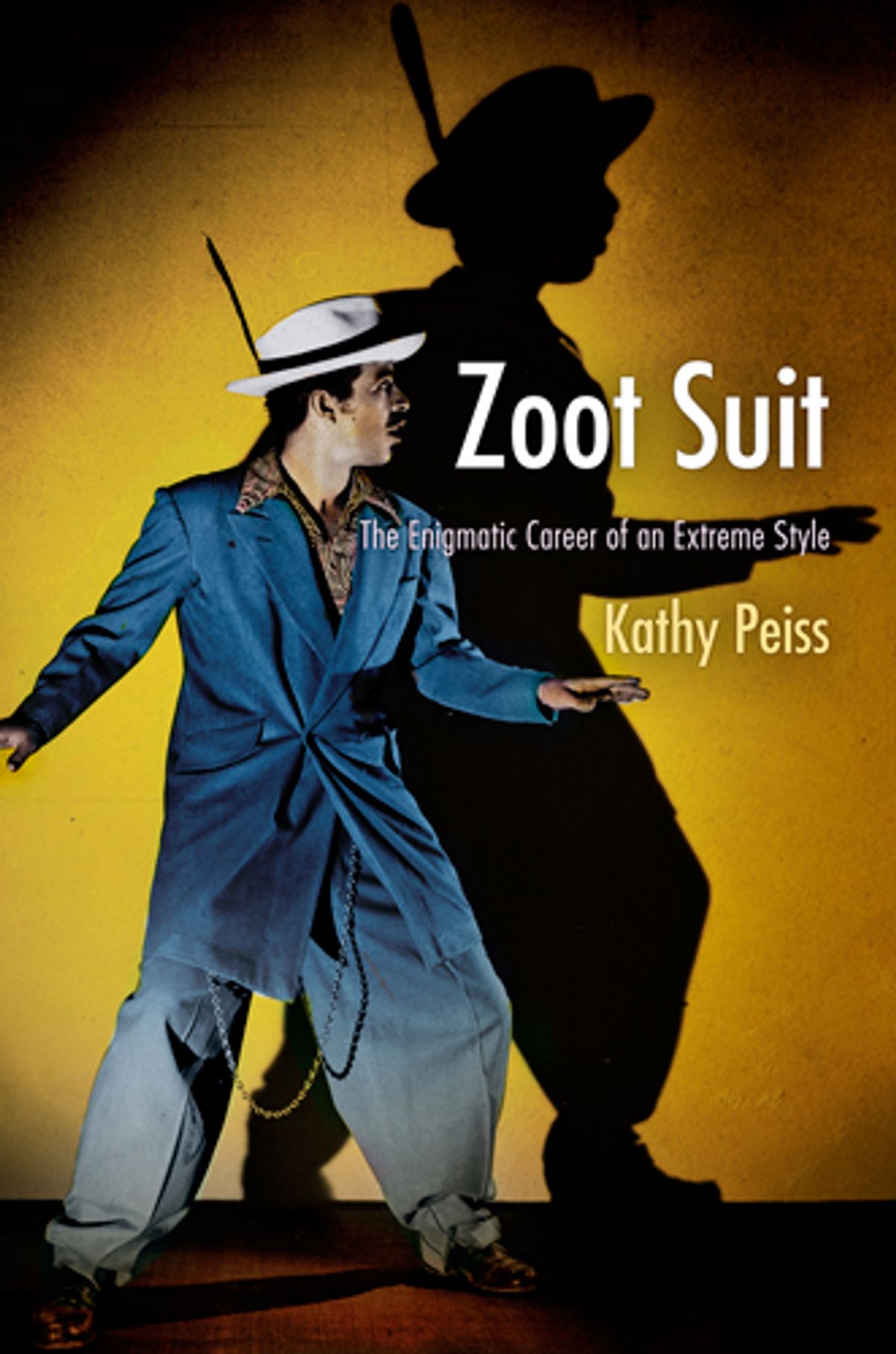

During World War II, in the midst of racial conflict during a period of already heightened fears, the United States experienced a wave of wartime tensions and explosions of violence from New York City to Detroit to Los Angeles. But only in Los Angeles were such displays of violence attributed to something seemingly harmless: —the zoot suit. The fierce demonstrations of unrest in Los Angeles during June 1943 were not labeled as race riots or as vigilante violence, but rather came to be known as "zoot suit riots." Kathy Peiss examines the cultural implications and symbolic power that the zoot suit had in American history in her new book Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style.

The goal of Peiss' research is to explore how such an iconic piece of clothing captured the attention and imagination of people across the country and throughout the world. The suit managed to generate a variety of meanings. Some interpreted it as a political statement, while others saw the suit merely as a fashion choice.

Peiss asks several key questions in order to understand how youth from many different cultural and social backgrounds altered the political landscape of wartime America. In particular she wants to examine the extent to which the zoot suit was a symbol of political resistance, a claim made by previous scholars who have written about this piece of fashion.

In this sense, the book is a critique of those scholars who often "understand clothing as primarily having a political meaning so that aesthetics are subsumed under the political." Although this time period did see a shift in growing political awareness among Mexican-Americans and increasing civil rights activism, she says, Peiss argues that the clothing worn by marginalized groups does not necessarily translate to political resistance. Clothing, much like any other item of cultural significance, has multiple meanings and the important question to consider is who is applying the meaning.

After its popular emergence in the 1940s, the zoot suit took two trajectories according to Peiss. One came out of the specific experiences of the war years—"in the changing configurations of ethnic and racial minorities, the new opportunities for work and leisure, a government clamp-down on textiles and clothing styles, and a press and popular culture attuned to these changes." This trajectory concentrated on the wearers of the suit and of the cultural processes that transformed a piece of clothing into a sinister symbol.

The other path focused on the interpreters of the suit—journalists, ministers, reformers, public officials, and academics who made fashion the subject of political interpretation and linked it to social behaviors. Peiss argues that such designations may tell the historian much more about those producing the interpretations of the suit than about the personal views and reflections of the zoot-suited men.

The book is organized into six chronological chapters chronicling the rise and transformations of the zoot suit. In chapter one, Peiss examines the making of the zoot suit; not so much the physical construction (although she does allude to the conflicting origins stories), but how the United States asserted a regulatory role in manufacturing and retailing to eliminate wasteful use of textiles. Such regulations affected the manufacturing, retailing and marketing whose impact could not be expected. Chapter two attempts to explore how the zoot-suiters understood themselves. Despite limited evidence, the author argues that in order to truly understand the suit, the historian must move past the quintessential African and Mexican American wearers to examine the youths of varying ethnic, regional and socio-economic class backgrounds. While the suit may have meant many things in its early stages, "political valence of the style was not foremost in the minds of those who wore it." Following the wearers' self-identification, Peiss delves into how others viewed and gave meaning to the suit in chapter three. Here she discusses how those who observed the suit, but often did not wear it, such as journalists, songwriters and animators utilized the suit to make commentary on American life during a time of war.

Chapter four examines the zoot suit riots themselves, starting with Los Angeles on June 3, 1943. Fifty sailors armed with improvised weapons targeted young Mexican Americans wearing zoot suits. While a singular event, the riot was the climax of years of growing discontent between Los Angeles whites and the rising number of racial and ethnic minorities entering the city in search of jobs. Similar assaults quickly spread to other cities that month including Philadelphia, Detroit, Richmond and Harlem. Understanding how a style which had once communicated a variety of meanings became tied to racial youth and criminality is crucial, according to the author, in assessing how the zoot suit came to be viewed as an expression of political resistance. Delving further into the riddle the suit created, in chapter five Peiss examines the different meanings that anthropologists, sociologists and historians developed regarding the suit as the social and behavioral sciences provided the language for the debate. This language influenced how the zoot suit came to be perceived around the world, which is the premise of chapter six. From Mexico to Canada, Africa and the Caribbean, the zoot suit quickly appeared outside of America as young men adopted the fashion for any number of reasons. By looking at how the suit spread along different relays of transmission, including personal encounters, American mass media, and even American government and private relief programs, Peiss argues that "wherever zoot suiters appeared, controversy followed…the aesthetic of an extreme style that incorporated elements of Western clothing conveyed a range of meanings," however conscious or subtle those meanings may have been.

Peiss pays close attention to the available evidence and critiques the conventional assumptions about the zoot suit, writing in a clear and engaging style in order to construct an important argument. She also provides the reader with an entertaining book which explores much more than merely fashion, but race, ethnicity and social understanding during a critical moment of American history.