According to official accounts from the Chinese Communist Party, “The ‘cultural revolution,’ which lasted from May 1966 to October 1976, was responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the state and the people since the founding of the People's Republic.”

While the Cultural Revolution's objectives were difficult to discern at the time, the movement grew out of Mao Zedong’s quest to regain the political power he lost following the failure of the Great Leap Forward (1958—1962) and his fear that enemies in the Chinese Communist Party planned to place China back on the capitalist road. Yet, Mao's call to a new generation of revolutionaries resulted in ten years of bloody factional fighting that paralyzed China's halls of power and left no corner of the country untouched.

Despite the wide-reaching impact of the Cultural Revolution, historians have cast the movement as predominantly urban and responsive to the imposition of military order. Dong Guoqiang and Andrew G. Walder's A Decade of Upheaval: The Cultural Revolution in Rural China widens the scope of the revolution by presenting the first sustained historical analysis of the movement in a rural Chinese county. By venturing into the countryside, Dong and Walder extract lessons that challenge many of the fundamental assumptions about the Cultural Revolution—beginning with where it took place.

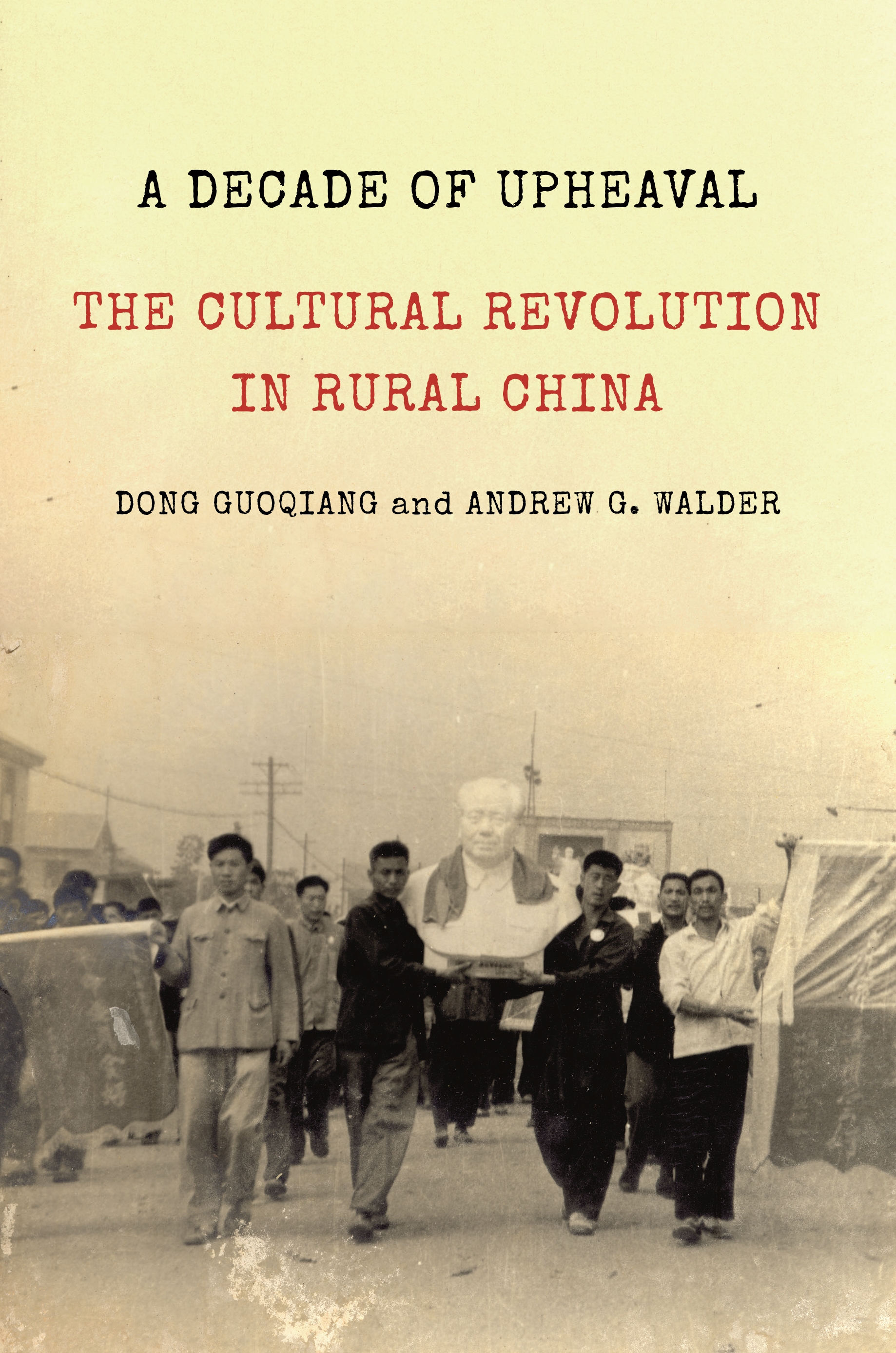

Tianjin Yan'an Middle School celebrates the Cultural Revolution, 1968.

The first two chapters introduce Jiangsu Province's Feng County, where this study is set, and the warring factions that would make the area largely ungovernable from 1966 to 1976. By the start of the Cultural Revolution, Feng County was one of China's poorest. With less than three percent of the county's population living in towns, the region was decidedly agrarian—even for China in the 1960s. What Dong and Walder demonstrate in A Decade of Upheaval is that even remote Chinese counties were not immune to the violent excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

Throughout much of the book, the authors carefully trace the ever-shifting balance of power between Feng County's two leading revolutionary organizations: Paolian (Bombard the County Party Committee United Headquarters) and Liansi (The Feng County Proletarian Revolutionary United Headquarters).

Thanks to an impressive array of sources, including oral histories and six well-preserved notebooks and diaries, A Decade of Upheaval covers the episodes in the conflict between Paolian and Liansi in stunning detail. Following the May 16th Circular, the central party document that launched the Cultural Revolution, local students began kidnapping and attacking county officials.

The authors make the case that Feng County's initial unified revolutionary group splintered following the return of the county’s now more radical college students and intense debates over how best to punish local officials. Paolian was the first faction to develop; its emergence, in turn, spurred the creation of Liansi. In subsequent chapters, Dong and Walder demonstrate how Feng County's factions waged a decade-long battle, not for power but survival.

A rally on cow demons and snake spirits during the Cultural Revolution.

Chapters three and four cover the military intervention in Feng County. Most Western histories argue that the Cultural Revolution plunged China into “chaos and anarchy until the military intervened to restore order.”A Decade of Upheaval makes arguably its most significant departure from other histories of the Cultural Revolution by demonstrating how military intervention exacerbated and perpetuated factional conflicts in Feng County.

Military authority in the county was divided between the People's Armed Districts (PAD) and the People's Liberation Army's 68th Army Corps. Over the course of the Cultural Revolution, the PAD would become closely associated with Liansi while the PLA grew sympathetic to Paolian. Through the book's middle chapters, Dong and Walder demonstrate how each time control changed from one military authority to another, the balance of power between Paolian and Liansi shifted with deadly consequences.

A Decade of Upheaval's final chapters cover the central government's largely abortive efforts to forge order out of the chaos of Feng County. Given the failures of military leadership in the region, the central authorities forced the factional leaders into study classes in Beijing designed to bring an end to the violence. But as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, the leaders of Paolian and Liansi mistook the meetings as opportunities to voice their grievances. In reality, political leaders in Beijing proved less interested in the stories of each side’s excesses than they were in bringing the county’s violent saga to an end.

Dong and Walder demonstrate that the final obstacle to ending Feng County's factional clashes was Beijing itself. Despite Feng County's remote location, it was China's unpredictable national politics that shaped the conflict in Feng County. For example, when the first study classes in Beijing ended in May 1970, the leading PLA officers left Feng County. Unrestrained, Liansi and their allies in the PAD gained the upper hand and immediately targeted Paolian and its supporters. The subsequent campaign resulted in the torture, murder, and suicide of numerous Paolian supporters.

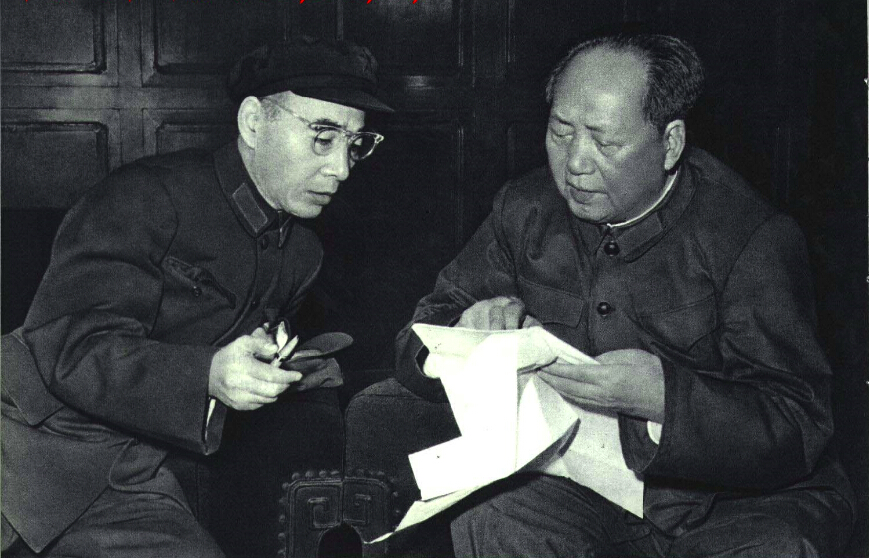

A picture of Mao Zedong (right) with Marshal Lin Biao (left) in 1966.

From this point, Dong and Walder convincingly show that Paolian would not again challenge Liansi's dominance of the region until after the downfall and mysterious death of Lin Biao, Mao’s successor, in 1971.

Lin had long been one of the most radical proponents of the Cultural Revolution, but in the years following his death, the political backlash against Lin and his policies created opportunities to seek retribution for those who had suffered under earlier phases of the Cultural Revolution. Thus, despite the deeply personal and local character of the conflict, the authors make a strong case that national politics set the tone and tenor for the Cultural Revolution in Feng County.

A Decade of Upheaval is a short book, but it makes a sizable contribution to studies of the Cultural Revolution. Paradoxically, however, the book's greatest strengths also present its most significant weaknesses. Although the authors collected sixteen oral histories and six diaries, one individual, Zhang Liansheng, becomes the book's chief informant. While Zhang and his faction Paolian are covered in stunning detail, it is clear that the authors could not gain the same degree of access to sources from Liansi. This imbalance raises issues for a book about a factional conflict, but the authors navigate these challenges well.

There is also the question of Feng County's representativeness. The book masterfully shows that even the most remote counties could be drawn into the Cultural Revolution’s national maelstrom, but the question remains of just how representative Feng County is. Are the lessons extracted from the Feng County experience during the Cultural Revolution applicable to other places in China?

A Decade of Upheaval leaves the answer unclear. But one thing is certain, while the fighting between competing factions seems to have been in pursuit of political power, the consequences of defeat—torture, death, and the loss of jobs—meant it was individual and collective quests for survival that ultimately fueled China's “decade of upheaval.”