In 2017, Canadians marked the 150th anniversary of their nation. But the Canada that was created in 1867 excluded the people who already lived there. This month historian Susan Neylan charts the ways Aboriginal Peoples have been treated by the Canadian government and examines how the ideals expressed in Canada’s motto “Peace, Order and Good Government” have not applied to Indigenous people.

On July 1, 2017, as a crowd gathered to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday on Parliament Hill in the nation’s capital of Ottawa, a group of Indigenous activists, the Bawating Water Protectors, erected a teepee. In defiance of the uncritical vision of Canada’s past held by many Canadians, this act functioned as an Indigenous ceremony and as a declaration of Indigenous presence on this land that long predates the country’s emergence as a Dominion in 1867.

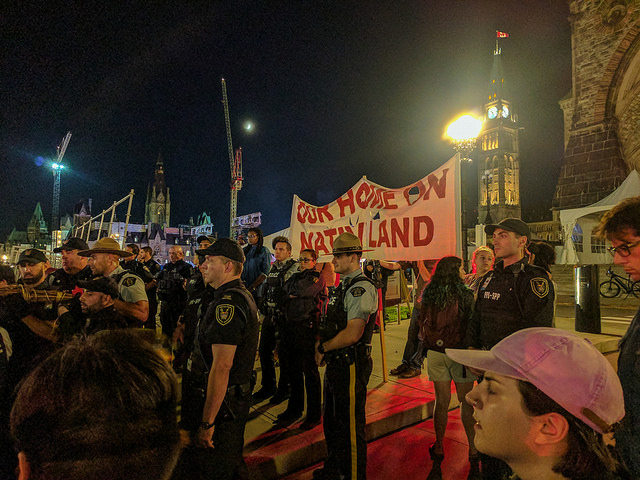

Protesters on Parliament Hill during Canada’s 150th birthday celebrations in 2017 [photo credit: TML Weekly Information Project].

Canada’s Houses of Parliament (its House of Commons and the Senate chambers) sit on the unceded traditional territory of Omàmiwininiwak (Algonquins), which also made this action a reoccupation of a traditional homeland. When the tepee went up the police had attempted to remove the protestors. But security authorities soon had a change of heart and allowed them to move to a more central location in the shadow of the Peace Tower next to the main stage.

The Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, personally met with the Indigenous activists in the tepee to listen to their concerns even as the official national celebrations commemorating that history—which had so failed Indigenous peoples in Canada—were heating up.

The occasion of Canada’s sesquicentenary has generated much discussion about Indigenous peoples and their history of colonialism under the Canadian nation state.

On one hand, public awareness of the problematic nature of the relations between the Indigenous peoples and settlers from other continents is likely greater than it has ever been.

Over the past half century there has been a rise in Indigenous organization, constitutional recognition of Aboriginal peoples and rights, new treaties and respect for Indigenous oversight of economic development within their homelands, and important legal decisions in the country’s highest courts.

An estimated 3,000 supporters of the Idle No More movement occupied Parliament Hill in 2013 (left). A protest in 2013 by members of the Nipissing First Nation and non-Aboriginal supporters in Ottawa over weakened environmental laws (right).

A series of high-profile resistance movements and events—the grassroots Idle No More movement (2012-present), the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2008-2015), and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2016- present), to name but a few—have awakened the country to the urgency of Indigenous issues. Some Canadians look to history to make sense of the legacies that inform native people’s struggles today.

On the other hand, uncomplicated and idealized visions of Canada’s past abound at the popular, public level.

Many assume that the Canadian motto “Peace, Order, and Good Government” informed the practice of Canadian “Indian” policy. Instead, violence, disorder and mismanagement, and a colonizing government have characterized Indigenous peoples’ experiences with the state.

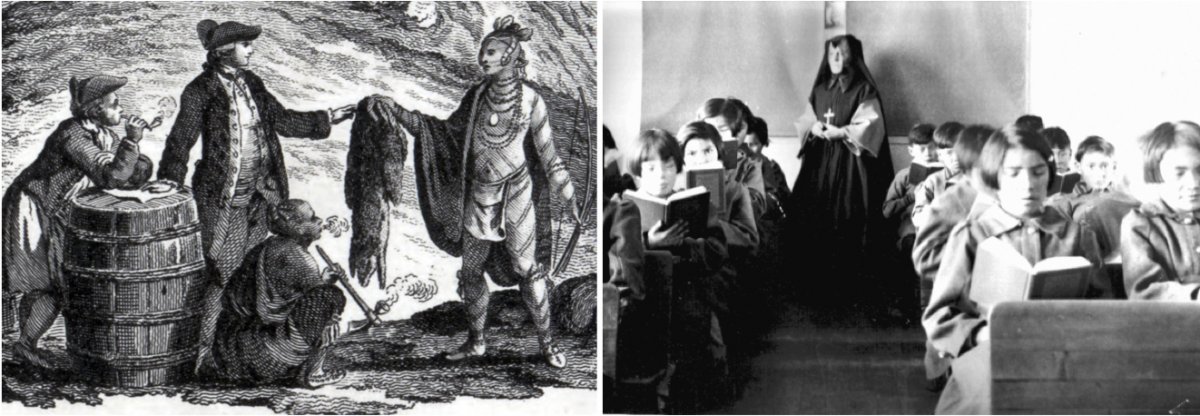

A 1777 depiction of French and Indian fur traders (left). Students of St. Anne’s Indian Residential School in Fort Albany, Ontario around 1945 (right).

Birthdays and National Origin Stories

"It has been very trying for Indigenous populations to have their existence annulled—that’s what the last 150 years have been. The 150th anniversary has to be marked by the fact that things have to change. We must confront our colonial thinking and attitudes and redefine what Canadian-ness means. We must move beyond the false notion that Canada was founded by the French and the English, recognizing that we started off with the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, and have become a society that thrives on diversity and knows how to share resources fairly among everyone." – Karla Jessen Williamson (Inuk), June 2017.

A century and a half ago, three colonies in British North America united to form the new Dominion of Canada. Popular understanding of this moment often refers to the “birth” of an independent country. On July 1, 1867, the four new provinces (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec) constituted a tiny fraction geographically of what has become Canada today.

Canada in 1867 was hardly an independent nation. It had no power to negotiate agreements with external foreign nations, no standing army, no national flag or anthem, and no power to amend its own constitution.

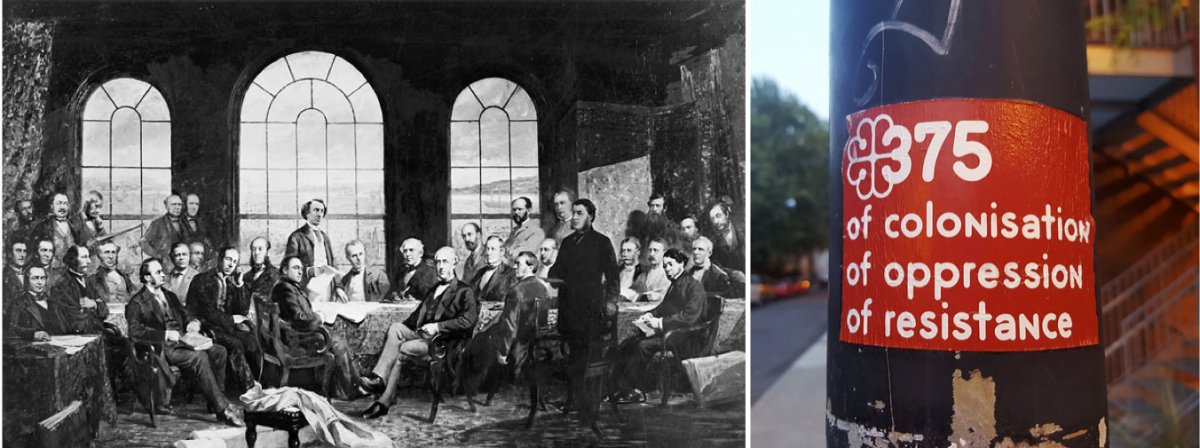

An 1884 painting depicting the Conference at Quebec in 1864, which settled the basics of confederation for the British colonies of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick (left). A 2017 sign in Montreal emphasizing 375 years of colonization, oppression, and resistance since European arrival (right).

Subsequently borders to the provinces were expanded and the country grew as other colonies and British-claimed territories joined or were added (Manitoba and the Northwest Territories in 1870; British Columbia in 1871; Prince Edward Island in 1873; Yukon Territory in 1898; Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905; Newfoundland and Labrador in 1949; and Nunavut, created in 1999).

However, Confederation as a process was not a democratic creation—there were no plebiscites (except in the cases of Newfoundland and Nunavut) and until the most recent additions, several groups were excluded from direct participation, Indigenous peoples among them. When Indigenous peoples did have input—for example, when Manitoba entered the Confederation in 1870—it was quickly disregarded.

A time-lapse map showing the changes to Canada's borders from 1867 to 2000.

Given they formed the majority population in all of the western and northern provinces when each joined Canada, lack of consultation followed by subjugation are more historically accurate descriptors of what Confederation meant for the Indigenous peoples.

Canada was created on top of Indigenous territories. Indigenous peoples’ place in the national narrative of the “birth” of Canada has been minimized and viewed as peripheral to the dominant culture’s stories.

The history Canadians don’t like to tell is that Canada’s nation-building has come at the expense of its Indigenous peoples.

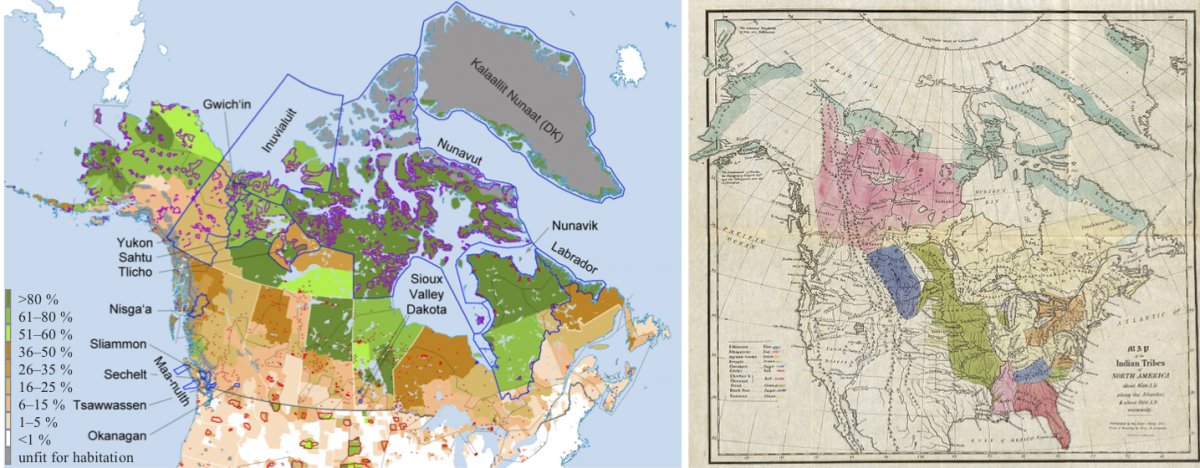

A map of the population density of indigenous people at the start of the 21st century (left). An 1836 map depicting the estimated areas of First Nation tribes in the 1600s (right).

“What is it about us you don’t like?” The Erasure of Indigenous Peoples

Canada identifies three different Indigenous peoples (constitutionally referred to as Aboriginal peoples) within its borders: First Nations are “Indians” and the federal government recognizes both collectivities (First Nations) and individuals, defining persons as either having legal “Indian status” or as being a “non-status Indian” according to colonially imposed criteria (which include residency, previous identification, and blood quantum).

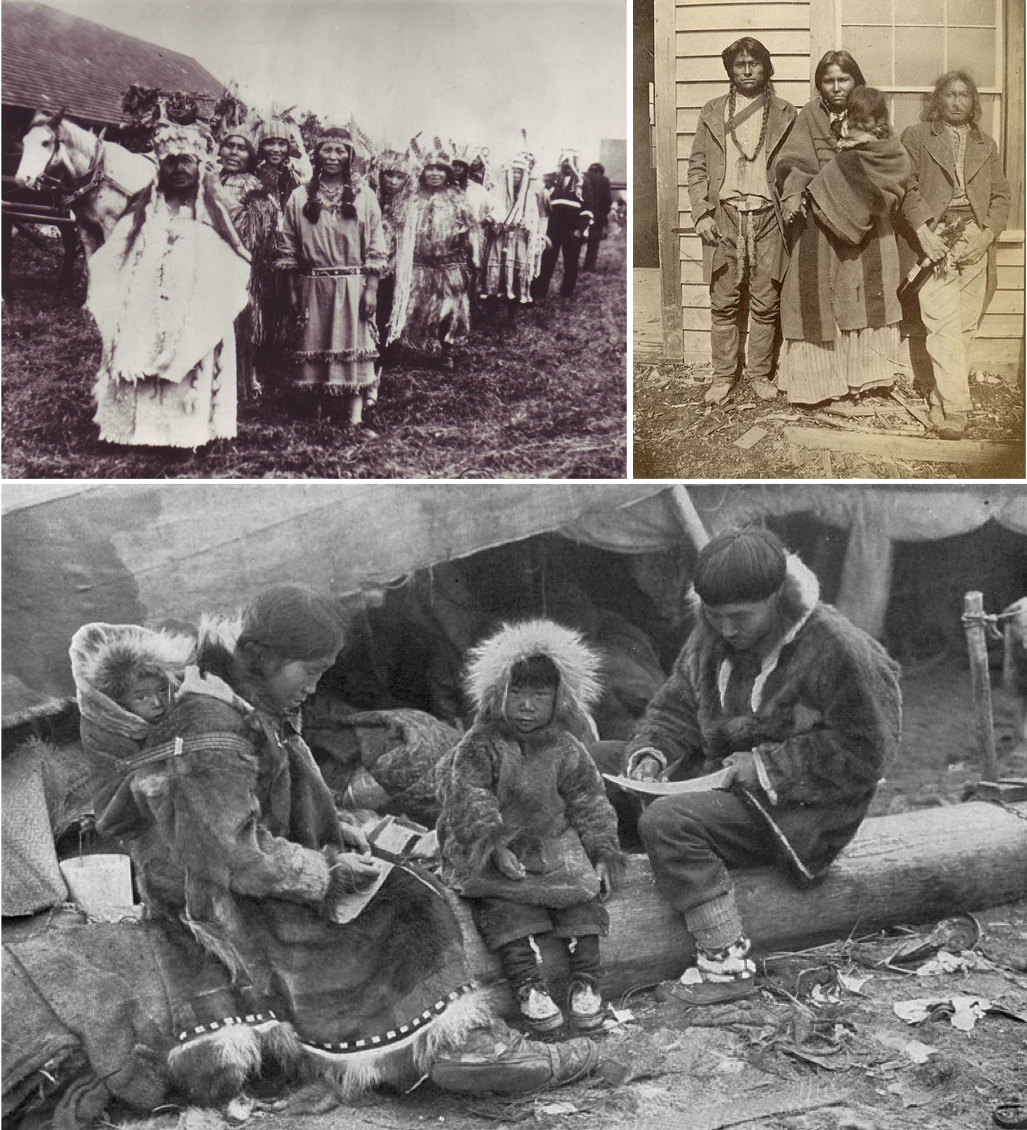

A group of Chehalis First Nations around 1910 (left). Métis at Fort Dufferin in Manitoba who were hired as scouts for a border survey in 1872 (right). An Inuit family in 1917 (bottom).

The second group is the Inuit (singular: Inuk), formerly labeled Eskimos, who are the original people of North America’s arctic. The third group are the Métis, people of Indigenous and European ancestry who emerged from distinct communities and historic circumstances, such as the fur trade, to embrace an Indigenous identity and culture distinct from either their Indigenous or European roots.

Collectively, the Aboriginal Peoples make up 4.9% of Canada’s current population.

The Canadian Minister of the Interior explaining the terms of Treaty #8, an agreement between Queen Victoria and various First Nations of the Lesser Slave Lake area over land and entitlements, in 1899 (left). Prince Arthur at the Mohawk Chapel in Brantford, Ontario with the Chiefs of the Six Nations in 1869 (middle). Nakoda chieftains meeting with King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II in Calgary in 1939 (right).

In a practical sense, the formal creation of the Dominion of Canada did not constitute a dramatic departure from earlier Indigenous-settler relations. “Indians” fell under federal jurisdiction and relations with Indigenous peoples were expected to follow existing policies and practices established by the British and their colonies. Hence the legal standing of existing treaties and reserves established prior to 1867 was recognized and adopted by Canada.

So too were general principles, such as those laid out in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (working out the details of the peace at the end of the Seven Years War/French-Indian War) and ratified by many Indigenous nations at the Treaty of Niagara in 1764, which stipulated that only the Crown could negotiate with Indigenous nations and there would be no land surrenders without Indigenous consent.

This proclamation is significant because it meant that Canada tacitly recognized some degree of Indigenous sovereignty and ownership over the territories it inhabited, even as it frequently contradicted this fact through actions.

Indigenous-settler relations were by no means unproblematic prior to Confederation. But what Indigenous people believed were nation-to-nation agreements of peace, the Canadian government viewed as real estate deals intended to extinguish Indigenous claims to land ownership and designed to remove or restrict rights of access to resources.

A map of the approximate borders of treaties between First Nations and Canada.

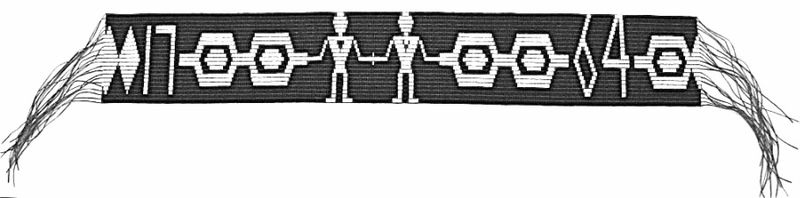

When the first prime minister of Canada, Sir John A. Macdonald, developed what he termed his “National Policy” in the late 1870s, one of its three central facets was the resettlement of Indigenous lands in the West by immigrant newcomers. Homesteading policies (such as the 1872 Dominion Lands Act) were created even before treaties were signed, suggesting that expediency and opportunity trumped genuine regard for Indigenous land rights.

Indian reserves (rather than reservations, as they are called in the United States) were Crown lands allegedly held in trust by the state for First Nations (and the majority remain so to this day). Yet in practice Canada has found all sorts of ways to cut off pieces of them, or to lease them out to logging or mining companies. Reserve residents have not received full market value for these land appropriations at any point.

An 1883 advertisement for land in western Canada.

The Indian Act in 1876 consolidated all existing legislation relating to First Nations into one place under the jurisdiction of the newly created Canadian federal government. It and subsequent amendments and revisions gave First Nations themselves no choice and little input. Although the new country was actively negotiating treaties with individual First Nations in the 1870s, the Indian Act unilaterally made many First Nations people wards of the state.

The Department of Indian Affairs was created in 1880 to administer the act and it remains in force today, though under the name “Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.” The Indian Act and its bureaucracy ensured them a negative and inequitable experience. By 1939, it also included Inuit in its mandate.

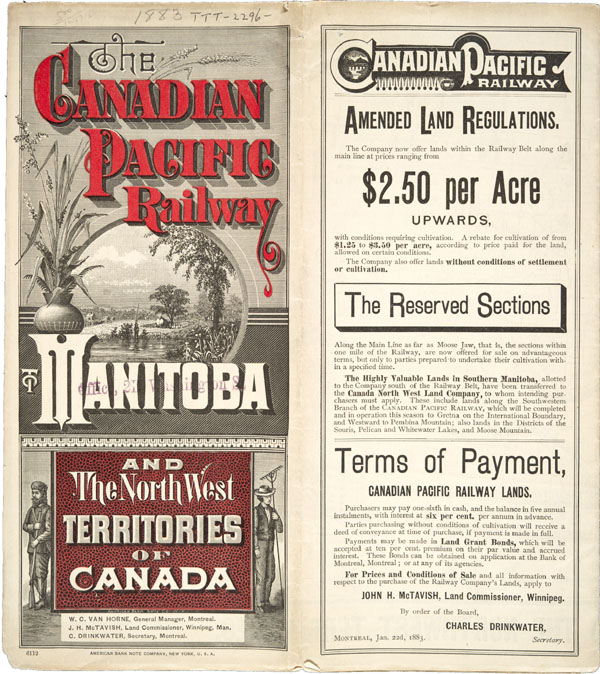

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development signs in the Canadian Museum of History (left, right).

The Indian Act implemented a myriad of regulations, controls, and limits on Indigenous peoples designed to crush their way of life and it created Indian agents who administered the rules and constantly monitored reserve communities.

It restricted Indigenous cultural practices, such as the potlatch, and banned the wearing of Indigenous regalia in public. Plains people needed Indian agent permission to sell their livestock or crops, and even to come and go on their reserves. Indigenous hunting and fishing were restricted, and many traditional economic activities, such as fishing weirs, were forbidden by law.

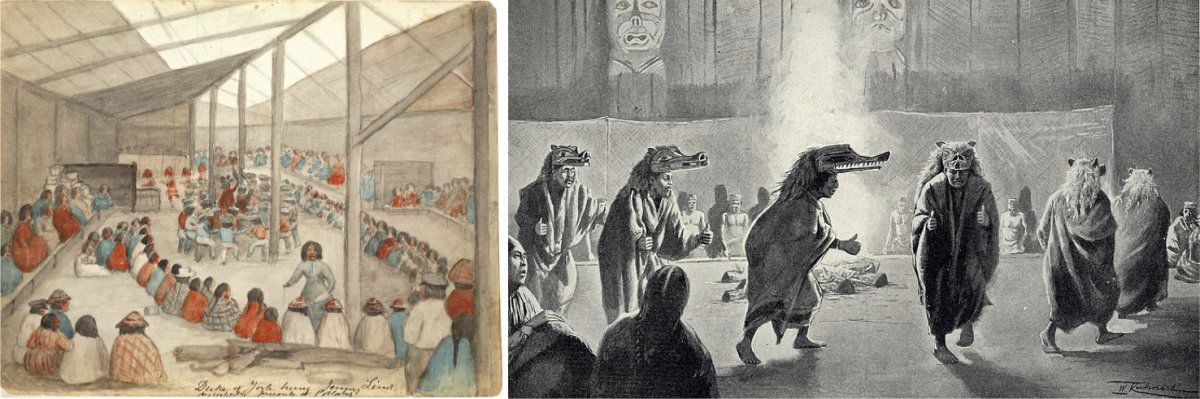

An 1859 painting of the Klallam people of Port Townsend, WA during a potlatch (left). An 1894 painting of a potlatch ceremony held by the Kwakwaka’wala-speaking people of British Columbia (right).

The Indian Act also assaulted traditional systems of governance, hereditary or otherwise, by imposing new political systems and elected band councils that mirrored Western models but subordinated them to the Canadian state. In short, it impeded the ability of Indigenous peoples to function as independent, self-governing peoples.

The Indian Act defines “Indianness.” It created a legal category—“status Indian”—and by extension, non-status Indians. In the United States, membership criteria are determined by the Indigenous nation. However, in Canada both the First Nation or Indian band and the status of the particular person have been largely determined by the Canadian state. Whereas Native Americans gained U.S. citizenship in 1924, in Canada, status Indians were not legally Canadians, nor could they vote in national elections until 1960.

Having status (which includes a mixture of blood quantum and previous identification as an “Indian”) affected whether someone could live on a reserve, hold membership in a First Nation band, receive treaty rights, access government programs, and claim “Aboriginal rights” under Canadian law. Those without status were denied access to these benefits.

The Indian Act could remove status, voluntarily or involuntarily, through a series of enfranchisement acts that set certain criteria based on perceived levels of acculturation or education. It also “de-Indianized” significant numbers of First Nations’ peoples through a gender-biased administrative sleight of hand. Until only a few decades ago in Canada when a status Indian woman married a non-status man, she ceased to be an Indian, as did her children.

In fact, the assumption that “Indianness” was patrilineal was a feature of the Indian Act and Canada’s definition of status Indians until legislation in 1985, which also turned over the right to determine membership to First Nations. Over 100,000 Indigenous individuals since then have applied to regain their status and status for their children.

The calculation of “Indianness” however remains truly flawed in the eyes of many Indigenous peoples. One must “reapply” to regain lost status; the government will not automatically reinstate status and requires rigorous, sometimes unobtainable, evidence to prove ancestry.

Describing this legislative erasure that could result in the total disappearance of “status Indians” within a few decades, Indigenous writer Thomas King sarcastically posed the question during his nationally acclaimed Massey Lecture for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), “What is it about us that you [Canadians] don’t like?”

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem” and the Question of Genocide

"This year, the federal government plans to spend half a billion dollars on events marking Canada's 150th anniversary. Meanwhile, essential social services for First Nations people to alleviate crisis-level socio-economic conditions go chronically underfunded. Not only is Canada refusing to share the bounty of its own piracy; it's using that same bounty to celebrate its good fortune. Arguably, every firework, hot dog and piece of birthday cake in Canada's 150th celebration will be paid for by the genocide of Indigenous peoples and cultures." – Pamela Palmater (Mi’kmaq), March 2017.

Canada’s intention to eliminate any separate Indigenous identity was official Canadian Indian policy for a long time.

Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Canada (1913-1932), put it bluntly in the speech he gave in 1920: “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. … Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”

Scott’s tenure was marked by particularly coercive policies and damaging legislative constraints for Canada’s Indigenous peoples, especially in terms of cultural repression and educational subjugation.

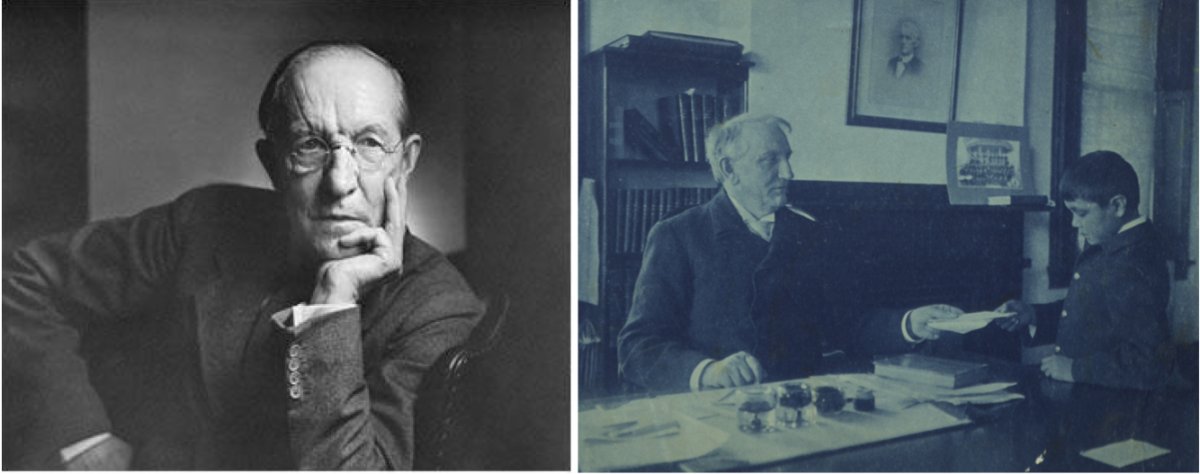

Canadian Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, in 1933 (left). Richard Henry Pratt with a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the 1880s (right).

Scott’s words eerily echo that other well-known quotation by a U.S. administrator, Captain Richard H. Pratt, in 1892: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one … In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

If you kill the “Indian in him” or her, if you completely rid yourself of not merely, in Scott’s words, “the Indian problem,” but of any communal or individual identification of Indigeneity, but you don’t actually physically kill people, is it genocide? When we call it something else—assimilation, imperialism, acculturation—do we fail to capture the gravity of willfully eliminating a people as a people, culture, or society? Do we miss the process of cultural genocide?

Conversely, when we use the genocide label for other kinds of killing (e.g. death through neglect, or bureaucratic elimination) do we diminish the weight of the word genocide? Many non-Indigenous Canadians bristle at the notion that a label like genocide applies to Canada, and rarely see ongoing Indigenous issues as the direct legacy of European colonial settlement in North America.

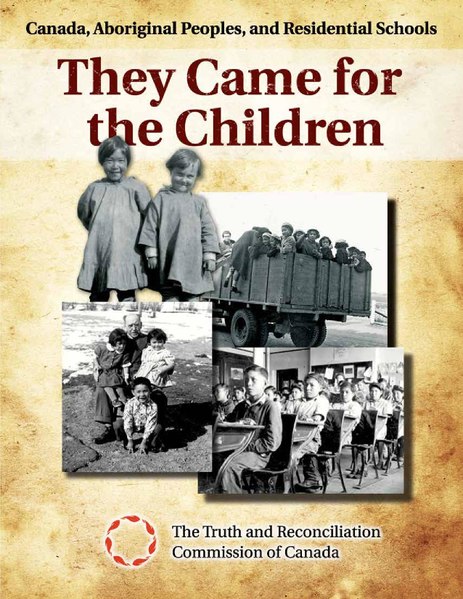

Reconciling Residential Schools

The shadow that most haunts the Canadian psyche is the history of removing Indigenous children from their home communities and compelling them to attend “Indian” residential schools, which led to the destruction of Indigenous individuals, communities, and cultures.

Although education programs began much earlier (for instance day schools located in Indigenous communities), the idea of residential institutions for Indigenous children, often located far from their homes, accelerated in the second decade after Confederation. As many as 150,000 children attended some 132 schools before the system was closed in the last quarter of the 20th century.

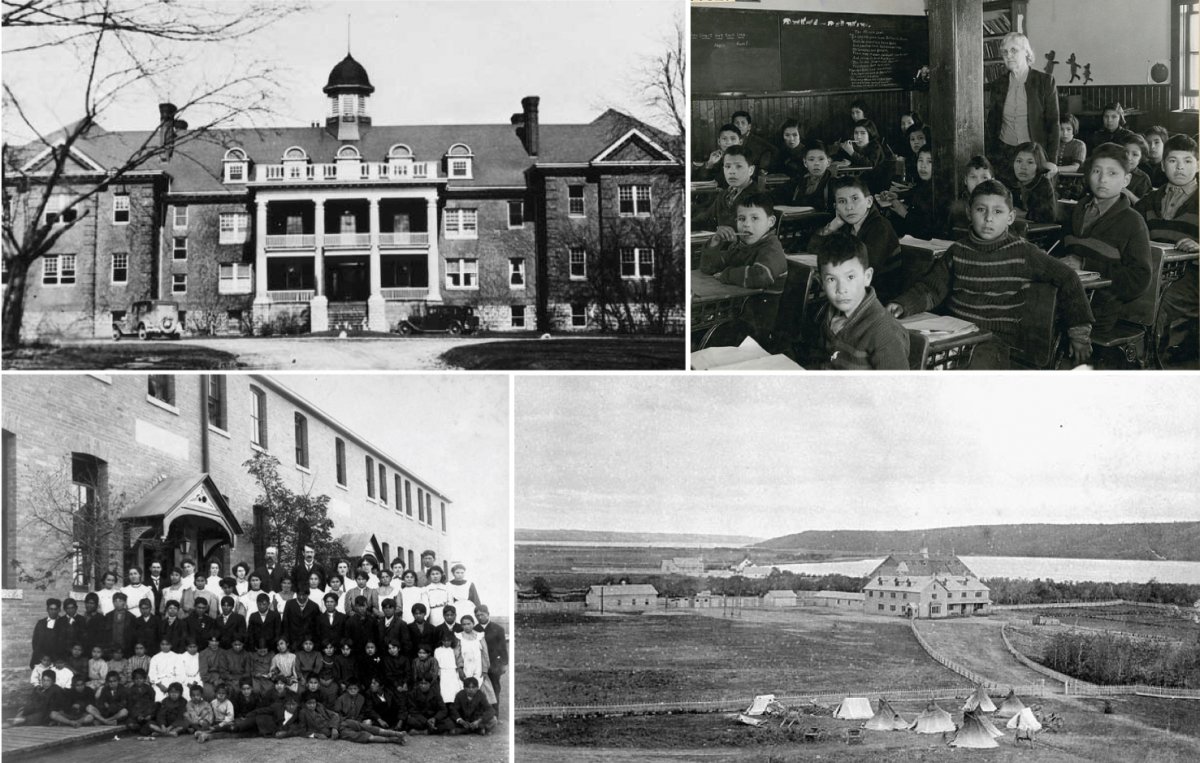

The Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School in Ontario in 1932 (top left). Students and a teacher at the All Saints Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan in 1945 (top right). Students and staff at an Indian School in Saskatchewan in 1908 (bottom left). The Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School in Saskatchewan around 1885 (bottom right).

Run in partnership with Catholic and Protestant churches in Canada, “Indian Residential Schools” followed an industrial school model whereby the academic curriculum was limited to elementary and intermediate levels and most students worked for at least half the day—chopping wood, farming, sewing, or doing laundry.

This system was similar to ones developed for Indigenous peoples in other former English settler colonies such as Australia and New Zealand, although in these countries church-run mission schools targeted Indigenous students of mixed heritage rather than the primarily “status Indians” enveloped by the Canadian system.

In 1886, an amendment to the Indian Act made school attendance mandatory for status Indian children, although it wasn’t until Scott’s tenure as deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs that the law was comprehensively enforced by government agents and Canada’s federal police force.

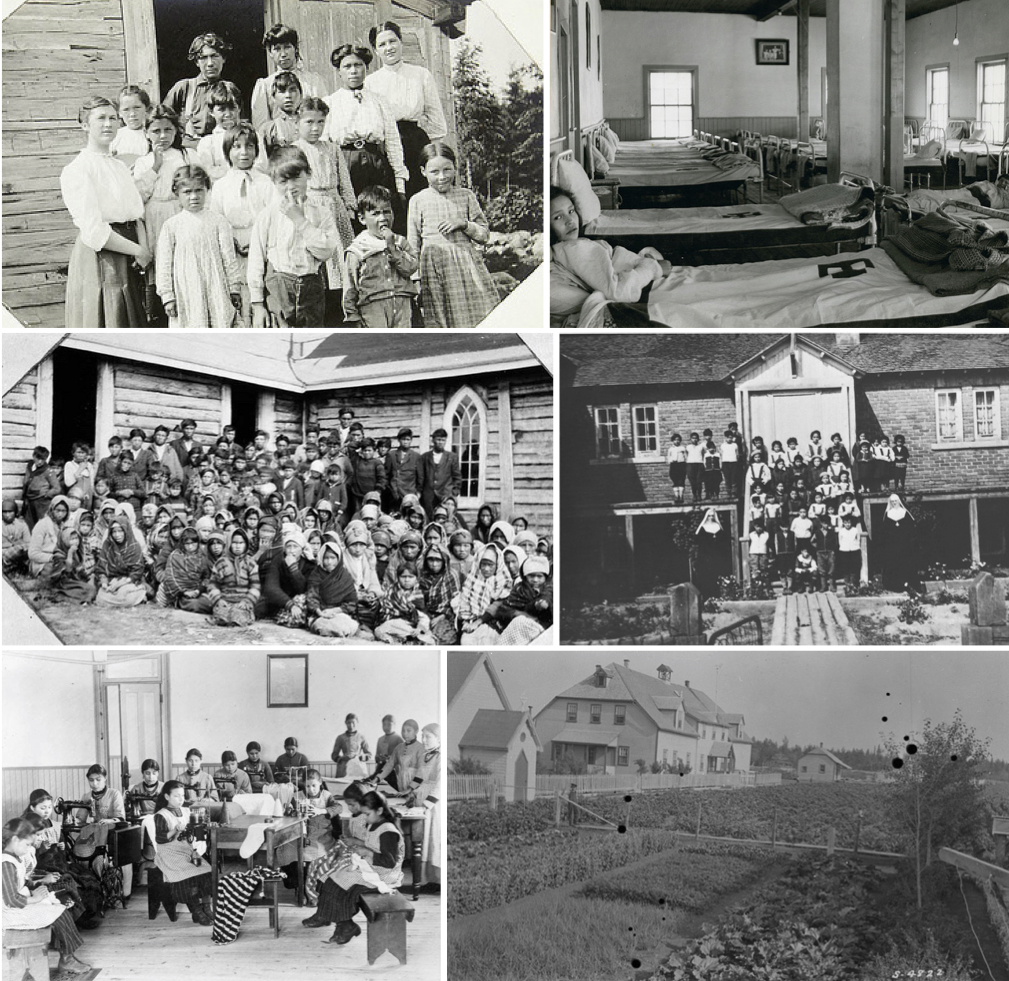

An Indian Day School at Bear Island, Ontario in 1906 (top left). The dormitory of the All Saints Indian Residential School in 1945 (top right). Students and staff of an Indian Day School in Ontario (middle left). Children and nuns around 1950 at an Indian Residential School in Quebec (middle right). Female students sewing at an Indian Residential School in the Northwest Territories (bottom left). The farm at St. Luke's English Church Mission School in the Northwest Territories around 1922 (bottom right).

The schools isolated children from their parents, communities, languages, and traditions. These institutions were devised to assimilate, Christianize, and acculturate. They failed miserably in terms of delivering education beyond minimal levels for all but the most exceptional students, and hence never facilitated the widespread assimilation into mainstream Canadian society as adults.

Chronically underfunded, overcrowded, and unhealthy, they were dangerous to the students who endured them. Indian Residential Schools led to rampant abuse, rape, neglect, and the death of at least 3,200 children.

Canada as a nation is now confronted with the history and legacy of what is increasingly accepted and officially spoken about as cultural genocide—which the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada defined as “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow a group to continue as a group” and cause them to “cease to exist as legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities.”

The term that Indigenous peoples have embraced to identify their experience is not ex-pupil or residential school alumnus, but “residential school survivor.” The effects of the schools went beyond the 80,000 living former students who directly experienced them because when they came back to their home communities they carried with them a plethora of social problems, dysfunction, and estrangement from their own Indigenous cultures and identities.

The intergenerational effect is called “residential school syndrome,” a combination of historical trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. It is a reality of Canadian society today and understanding the history of residential schools is fundamental to any process of reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

The last federally run residential school closed in 1996, and it was really only in the 1990s that the full scope of residential school abuses and trauma upon generations of Indigenous peoples hit the public consciousness.

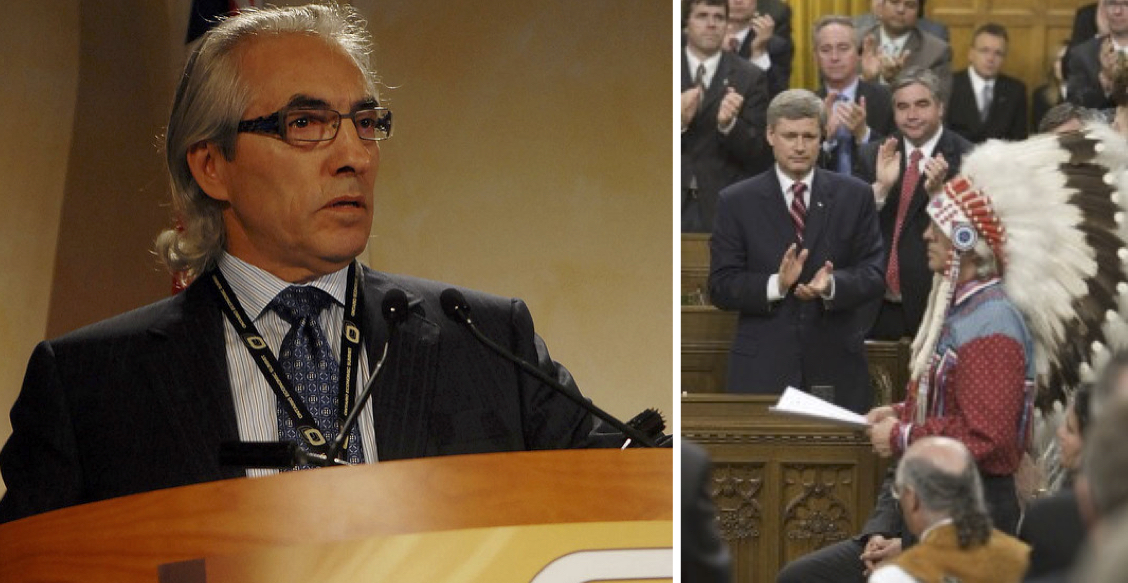

Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine in 2008 (left). Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Fontaine during Harper’s apology in 2008 (right).

These revelations of Canada’s dark past appeared when Indigenous leaders, such as Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine, first spoke openly about their own horrible experiences in the schools including sexual and physical abuses; when the churches started to issue formal apologies; when lawsuits representing over 10,000 school survivors were filed; and when a $350 million healing fund intended to support community-based projects was created. Prime Minister Stephen Harper gave an official apology only in 2008.

That year, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) embarked on an inquiry to document the history of the Indian Residential Schools by collecting testimonies from survivors, former school staff, and others, and by conducting historical research. These testimonies along with documentation and other historical materials are to be archived at a permanent National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

The logo for the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (left) and the logo for the Assembly of First Nations (right).

When the TRC presented its 94 recommendations—its Calls to Action—in June 2015, Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild told the gathered audience, “Above all, we must remember that this is a Canadian story, not an Indigenous one.”

This same message permeated the findings in the Final Report released in late December 2015. History education about residential schools, Indigenous-settler relations, and the history and legacy of Canadian “Indian” policy was especially prominent in these recommendations. The need to really know this country’s history including all the exclusions, erasures, and disturbing aspects was identified as both a problem to be addressed and the key element of meaningful reconciliation.

Rethinking Canada’s 150th Birthday

"This intended celebration can be an opportunity for Canadians to take stock of the past, celebrating the country’s accomplishments without shirking responsibility for its failures. Fostering more inclusive public discourse about the past through a reconciliation lens would open up new and exciting possibilities for a future in which Aboriginal peoples take their rightful place in Canada’s history as founding nations who have strong and unique contributions to make to this country.” –Executive Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, (2015).

In its final report, the TRC recommended that recognizing the place of Indigenous peoples in Canada’s past and present should be the ultimate message behind Canada’s 150 commemorations. Yet birthday parties rarely dwell on the kind of negative message the country would be forced to face.

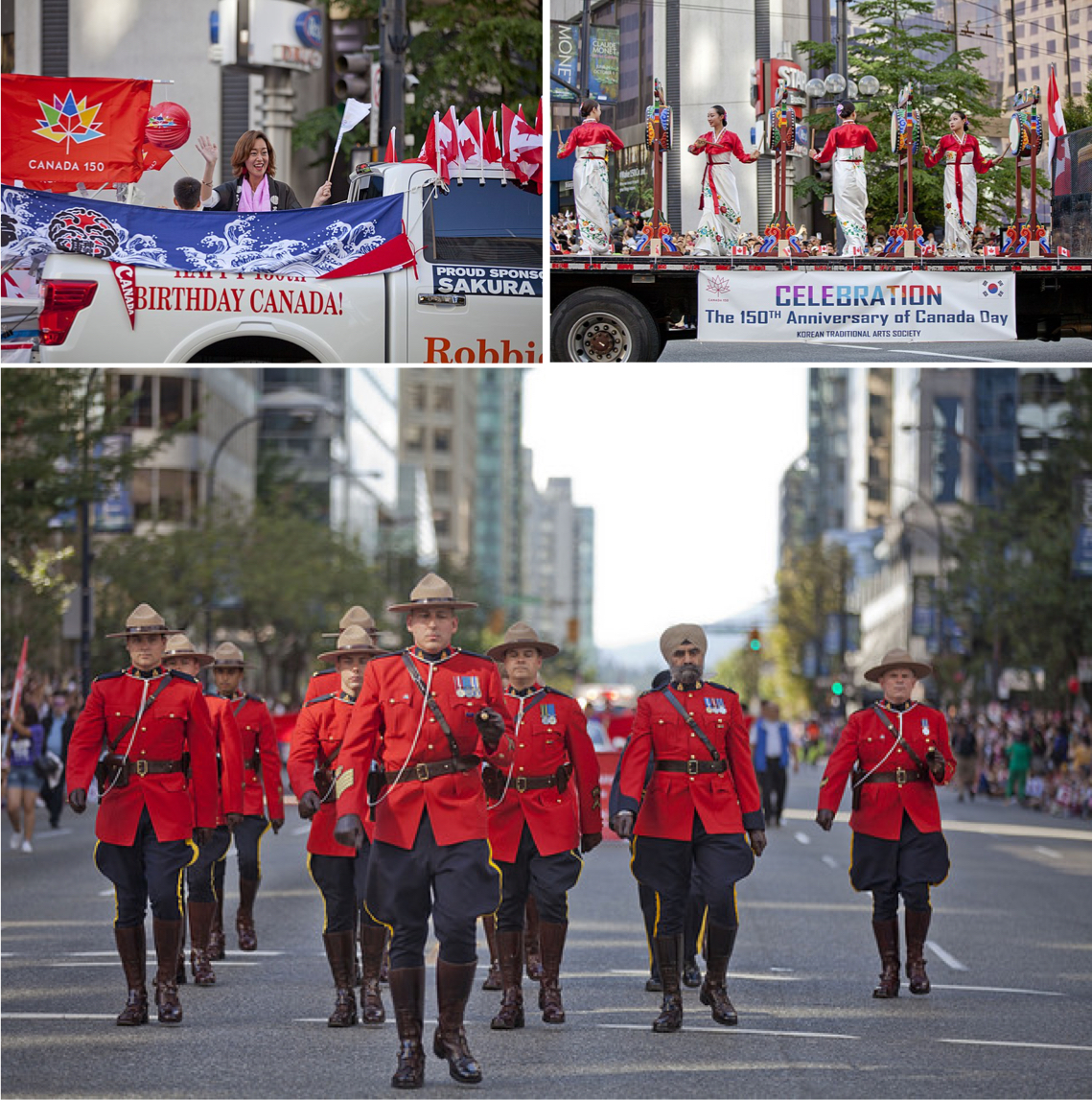

In the narrative Canadians tell themselves about their past and present, they see their country as tolerant and inclusive. It is not perfect, but when looking at gains made in the second half of the 20th century and onward, on many levels Canada has been a tolerant and inclusive country.

2017 Canada Day Celebrations in Vancouver (left, right, bottom).

It has embraced multiculturalism as a central identity, has a fairly welcoming immigration and refugee policy, has managed French and English nationalisms without separation of one from the other, and created a Charter of Rights and Freedoms to guarantee equity and equality for all.

This is why confronting the Indigenous experience that contradicts this image is so very difficult for non-Indigenous Canadians. Canadians rarely acknowledge the administrative control, appropriation of lands and resources, restriction of nearly every facet of Indigenous existence, including the right to define oneself, as a form of violence.

The reserve system, the Indian Act, and outright subjugation caused violent, severe, and lasting mental, physical, and cultural damage to Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Hiring a lawyer or actively pursuing Indigenous land claims was banned by law between 1927 and 1951. Forced sterilization programs in the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta, beginning in the 1930s, and continuing until the early 1970s, were disproportionately applied to certain segments of the Canadian population, including those of Indigenous descent.

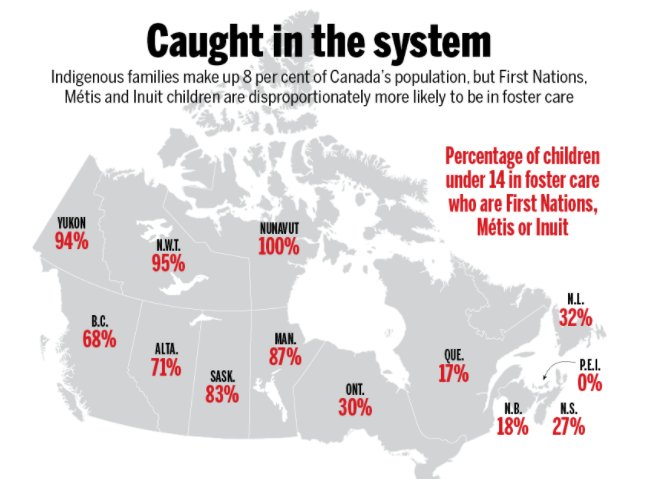

By the 1960s, although only 4% of the population, Indigenous children made up between 30 and 40% of legal wards of the state, and thousands of Indigenous children were removed from their parents and adopted by non-Indigenous families. In the half-century since, these numbers seem to have only increased. According to Statistics Canada’s data, in 2016, half of all the children under the age of four in foster care in Canada are Indigenous, more than ever attended the residential schools.

Willful neglect by the Canadian government also accounts for present-day negligence in terms of water quality on reserves, overcrowded housing, or substandard health care. Indigenous peoples continue to be overrepresented in Canada’s criminal justice system.

Health outcomes are no better. Today’s tuberculosis rates among status Indians are 31 times those for non-Indigenous Canadians, and among the Inuit, the risk of contracting TB is a staggering 186 times that of other Canadian-born non-Indigenous people.

When he was asked about the July 1 demonstrations last year, Trudeau said, “We recognize that over the past decades, generations, and indeed centuries, Canada has failed Indigenous peoples. We have not built the kind of present, the kind of future for first peoples, for First Nations, for Inuit, for Métis people across this country. We need to be doing a much better job of hearing their stories and building a partnership for the future.”

Demonstrators in Ottawa during 150th anniversary celebrations.

Rather than a celebration of Canada’s sesquicentenary, has this acknowledgement of Canada’s failure or the TRC’s call to action been a message received by the broader public?

Through a vast array of venues, numerous Indigenous voices challenge all Canadians to question their assumptions about the history of this country, ranging from a call to “unsettle” the story of Canada through “hashtagged” discussions like #resistance150, #unsettling150, and #decolonize150, to inverting national narratives through travelling art exhibitions.

If Canadians are willing to rethink how their nation-building unfolded and the enduring influence it has had on the Indigenous-settler relationship then and now, can this move us closer to acknowledging Indigenous peoples as founding peoples, whose inclusion in Canada means confronting a troubled past of colonialism as a history that matters?

Symbolic gestures of such inclusion abound.

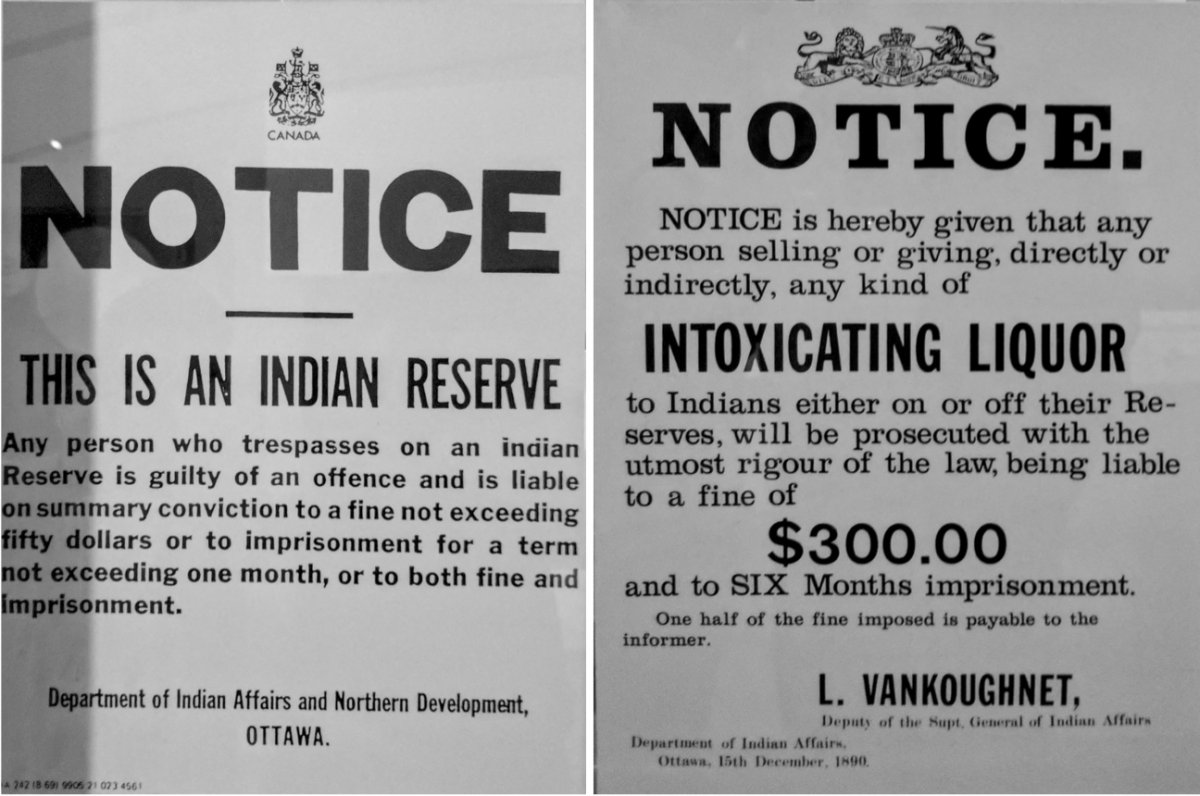

A special “Canada 150” ten dollar bank note features the image of Canada’s first Indigenous (Kainai First Nation) senator, James Gladstone (Akay-na-muka), as a “history-maker.” It also includes the pattern of the Métis sash (an important cultural identifier) and the stone-cut and stencil print of an owl by Inuit artist Kenojuak Ashevak.

One of the legacies of Canada’s centenary celebrations in 1967 was the creation of the Centennial Flame, a twelve-sided (to represent Canada’s then ten provinces and two territories) water fountain with a natural-gas lit flame at its center, located prominently along the walkway leading up to the Peace Tower and Centre Block on Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

A sesquicentenary project added a thirteenth side in recognition of Nunavut, a primarily Indigenous-inhabited territory in Canada’s eastern arctic that joined the country in 1999 as part of a larger Inuit land claims settlement.

Symbolic gestures are important but have more resonance when they lead to real change. And there is a worrying lack of momentum on many fronts.

Lately plagued by staff resignations, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls has been harshly criticized and has had to request a two-year extension to its mandate in order to complete its work.

Furthermore, this year Canadian racial tensions have been highlighted by court cases that saw all “white” juries acquit or dismiss charges in murder trials for slain Indigenous youth Colten Boushie and Tina Fontaine.

A proposal that the oath new Canadian citizens make at their swearing-in ceremony include an acknowledgement of the relevancy of treaties with Indigenous peoples as being part of the laws of Canada, still has not been enacted, although it was planned for 2018.

Indeed, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s website “Beyond 94” that tracks which of the recommendations made by the TRC, says to date 44 of the 94 Calls to Action have not even been started, while only 10 have been completed.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaking in front of Parliament in 2016 about missing and murdered indigenous women (left). A 2016 art installation depicting the backlog of unsolved cases with a sign proclaiming “Indigenous women cold cases. Because we do nothing” (right). A community-based art installation at Algoma University in 2016 to commemorate murdered or missing women from indigenous communities (bottom).

Certainly the moments of inclusion symbolized in the reconstructed fountain and plans for the citizenship oath mark a departure from the previous erasure of Indigenous peoples from the Canadian identity and history. There may be costs—emotional, financial, ethical—to understanding the dark side of Canada’s past—or, as many Indigenous peoples and their allies would remind us, to recognizing inequities, lack of justice, and oppression that continue to this day.

But what are the costs of not remembering and not seeing them?

A 2018 rally in Saskatchewan calling for justice for Colten Boushie.

Dr. Susan Neylan is an Associate Professor of History, at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. She acknowledges that she lives and works on the traditional territories of the Attawandaron (Neutral), Anishnawbe, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Facilitated by the Between the Lakes Purchase from the Mississauga of the New Credit First Nation, she also recognizes that she is on the Haldimand Tract, land promised to Six Nations, which includes six miles on each side of the Grand River.

Read Origins and listen to History Talk for more on Native American history: Canada 150; Native Sovereignty and the Dakota Access Pipeline; Treaties and Sovereign Performances at Standing Rock; Firearms and Native Americans; Native American Assimilation Policy; and the Creek Civil War.

Daschuk, James. Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013.

King, Thomas. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2012.

Manuel, Arthur. Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call. Toronto: Between the Lines Press, 2016.

Miller, J.R. Residential Schools and Reconciliation: Canada Confronts Its History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

Miller, J.R. Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada. 4thEdition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Regan, Paulette. Unsettling the Settler Within: Indian Residential Schools, Truth Telling, and Reconciliation in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011.

Saul, John Ralston. A Fair Country: Telling Truths about Canada. Toronto: Penguin Books, 2008.

Simpson, Leanne. Dancing on our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence, and New Emergence. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2011.

Vowell, Chelsea. Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada. Winnipeg: Highwater Press, 2016.