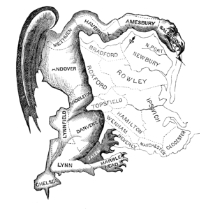

The political cartoon that led to the coining of the term Gerrymander. The district depicted here was created by the Massachusetts legislature to favor the incumbent Democratic-Republican party candidates of Governor Elbridge Gerry over the Federalists in 1812.

Alongside the Presidential nomination process, the most prominent American political news stories these days are about the heated, high-stakes struggles over redistricting. The modern era of reapportioning state and federal legislative districts began almost exactly a half century ago when the U.S. Supreme Court decided Baker v. Carr (1962). With the Supreme Court recently agreeing to hear a Congressional redistricting case from Texas, this month historian and legal scholar David Stebenne puts today's redistricting battles in historical perspective to understand better this decisive component of American politics.

Readers may also be interested in these recent Origins articles about current events in the United States: Unemployment, Energy Policy, Why We Aren't 'Alienated' Anymore, Populism and American Politics, Presidential Elections in Times of Crisis, Illegal Immigration, Detroit and America's Urban Woes, the Mortgage and Housing Crisis, and the 2nd Amendment Debate.

The news media today are full of stories about efforts across the United States to draw new state and federal legislative districts following the 2010 Census. Even the U.S. Supreme Court waded into that process very early, by agreeing to hear a legal challenge to a congressional redistricting scheme in Texas.

All of this news reflects the truly unprecedented levels of contention associated with the redistricting process this time. As soon as state legislative leaders propose new district maps, opposition swells, culminating in lawsuits and, at times, judicial rulings requiring legislatures to try again. The overall impression is of a process that has spun out of control, driven by narrow partisanship rather than public interest.

"Gerrymandering," the practice of drawing legislative district boundaries so as to maximize partisan advantage, is far from new. Elbridge Gerry, the Massachusetts governor whose name literally became synonymous with the practice, worked his magic to create a salamander-shaped district over two hundred years ago.

The modern era of legislative redistricting began more recently, however, when the U. S. Supreme Court decided a case known as Baker v. Carr in 1962.

The case involved a lawsuit brought by a man named Charles Baker, a Republican who lived in Shelby County, Tennessee, where Memphis is located. He sued the Tennessee Secretary of State, Joe Carr, because the Tennessee state legislature had not redistricted since the 1900 Census.

Thanks to population shifts over the preceding sixty years, Baker's district in Shelby County had roughly ten times as many residents as some of the rural districts with equal representation in the state legislature. The Supreme Court, by a vote of 6-2, found for Baker. In so doing, the Court announced that redistricting was an issue a court could resolve, thereby over-ruling earlier decisions that courts were not competent to decide such political questions.

Two years later, in a pair of decisions known as Wesberry v. Sanders (1964) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the Court found that the Constitution required all states to redistrict after each decennial census, and produce equal population districts for all state legislative and federal (i.e. congressional) seats except for those in the U.S. Senate.

These Supreme Court decisions produced a political revolution that dramatically changed the practice of American politics. We continue to grapple with the results today.

Legislative Districts before Baker

This redistricting revolution strove to tackle longstanding social and political issues in America, from the changing rural-urban relationship, racial discrimination, and the agricultural versus industrial foundations of the economy.

And it was a revolution not just in the mostly one-party, racially segregated South of that day. Many of the states of the North and West had also failed to redistrict regularly (often for decades), albeit for somewhat different reasons.

In fact, until the Court handed down its decision in Baker, the most important previous decision had been in an Illinois case known as Colegrove v. Green (1946), where the Court—reflecting its hands-off approach to the question of districting—declined to enter this "political thicket."

Like Tennessee, the Illinois state legislature had stopped redistricting after the census of 1900. Thus, by the time the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in the Colegrove case, almost half a century of legislative inaction had passed. By that point, a majority of all Illinoisans lived in Cook County (greater Chicago), but they had nothing like half of the seats in the general assembly or in the state's congressional delegation.

The origins of that peculiar state of affairs in the North and West had to do with three streams of migration to the cities there after 1870. The first consisted of the so-called "new immigration" from southern and eastern Europe. That mass movement of people greatly swelled the size of America's cities (almost all of them in the North and West) from the 1880s through 1915.

And then, just as that stream of immigration was cut off by World War I and postwar laws restricting immigration, a second stream of migration to America's urban centers began. This second mass movement of people was an internal one. It consisted primarily of southern blacks moving north and west to cities such as New York, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago and Los Angeles, in search of more economic opportunity and more legal and political equality.

These two streams of people and a third—the much more gradual movement from the 1870s through the 1940s of native-born whites from the countryside to towns and cities—made the USA a predominantly urban society by the 1940s.

Had state legislatures in the North and West faithfully redrawn legislative districts to keep up with those major shifts in population, no constitutional question would have arisen. In most cases, however, the state legislatures failed to act. Political boundaries were not usually redrawn after the turn of the twentieth century and districts were not divided into blocks of roughly equal population.

As a result, the voting power of those living in growing urban districts was numerically diluted while the voting power of their rural, largely native-born white counterparts was correspondingly enhanced. State legislatures, dominated by rural interests (because the country had once been almost entirely rural) refused to grant concessions needed to achieve more equal district sizes in terms of population.

Resistance to reapportioning seats in the U.S. House of Representatives also grew after 1911, when Congress fixed the total membership of that body at 435.

Up to that point the size of the House had grown as population did. Thereafter, reapportionment became much more of a zero-sum game in which states with growing populations gained seats and those with stable or shrinking populations lost seats. Drawing new lines for congressional districts in that latter context also fed opposition to reapportionment.

Such resistance eventually produced some very bad results. In Illinois, for example, by 1946 residents of Cook County paid 53% of the state's taxes. And the economic importance of Chicago to the state of Illinois greatly exceeded the fraction of the Illinois state legislature representing that city's residents.

Political corruption developed in consequence. The only way Chicagoans could exert influence in the legislature proportionate to the city's economic importance and population size was through the use of money. As one seasoned political journalist, John Gunther, concluded in 1946, "the only way Chicago can operate in the legislature at all is to try to buy it."

Despite these political deformities, the social, cultural and racial gaps were so wide between the minority living in rural areas (usually native born whites) and the rapidly growing majority of urban dwellers (often newcomers to the state, immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, and migrant blacks from the South) that rural residents and lawmakers feared surrendering their control over the legislature to Chicago.

That basic split only deepened during the 1930s and 1940s, when Chicago became one of the most strongly Democratic cities in the country in the context of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal policies. The rest of Illinois remained the Land of Lincoln, a state in which the rural areas were as strongly Republican as those of any northern or western state in the nation.

After the 1930s, therefore, redistricting meant not only transferring political power to the newcomers in the city; it also often meant transferring control of the legislature from the Republicans to the Democrats. In Illinois, as was true elsewhere in the North and West during the heyday of the New Deal, the last remaining bastion of GOP control was the state government, which Republicans tried very hard to hang onto.

Added to that source of resistance was the enduring importance of agriculture to the economic life of northern states like Illinois. The fraction of the population directly employed in farming fell steadily after the 1870s, but not the volume of crops or their dollar value. Instead, ever more agricultural commodities were produced by ever fewer people.

Thus, after the 1930s, redistricting also implied creating a situation in which agricultural interests would likely have been under-represented in the state's general assembly in terms of farming's economic importance to the state. Trading one form of economic under-representation (the cities') for another (farming areas') actively discouraged redistricting.

To make matters worse, the longer state legislatures waited to redistrict, the more drastic would be the resulting shift in political power, and the harder that change would be to bring about. Resistance to redistricting in the North and West hardened in the 1930s and 1940s.

And even though such a shift in theory was easier in the South, because few outsiders had moved into the region's handful of real cities from the 1870s through the 1940s, the one-party nature of Southern politics at that time fed resistance to change there, because the gradually growing Republican population in Dixie then was almost entirely metropolitan.

There was, of course, a racial dimension to this situation in the South. Rural areas there in 1900 tended to have more black residents than urban areas did, but as blacks migrated to Dixie's cities and larger towns over the following sixty years, that balance shifted somewhat.

If Southern blacks in the future were to gain greater access to the ballot, redistricting implied increasing their political power even more. In that respect, the northern and southern states were more alike than different.

Revolutionizing the Political Landscape: Baker and the 1960s

As the inability of the state legislatures to address the problem of urban underrepresentation grew, and efforts intensified to dismantle the racial segregation system in the South that kept most blacks there from voting, the U.S. Supreme Court was eventually prompted to act as it did in Baker and subsequent, related cases.

The justices were very conscious that they were doing some truly momentous. Chief Justice Earl Warren described the Baker decision in particular as the most important of his time on the Court (1954-1969).

In that case, Associate Justice William Brennan wrote the opinion for six justices. It found six criteria applied in deciding whether an issue constituted a political question that the Court could not resolve. All six involved separation of powers issues among the three branches of the federal government rather than federalism concerns (i.e., the federal government's relationship with the states).

The Court concluded that the Constitution did not commit the reapportionment issue exclusively to the other branches of the federal government (legislative and executive) and so courts could, at least in theory, decide such disputes.

That ruling cleared the way for later decisions in Gray v. Sanders (1963) where the Supreme Court applied a "one person, one vote" standard to statewide elections. It also made possible Wesberry v. Sanders (1964) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), which applied this standard to congressional districts and to both state legislative houses.

The one person, one vote standard seemed to be the only one a court could easily apply, as the dissenters in Baker had warned, and so its emergence was highly likely once the Baker decision was handed down. So, too, did the requirement that reapportionment take place promptly after each decennial census.

Changing social and political conditions in the country after Baker was decided in March 1962 also pushed the Court to apply those legal rules.

Even though there had been a nationally visible civil rights movement since the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56, that struggle had been contained through 1962. In May 1963, however, it became unmanageable in Birmingham, Alabama. Violent racial confrontation there and elsewhere in the South and the Border States grew sharply thereafter, and spread North and West to cities there with large black populations.

That turn of events put pressure on the Supreme Court to resolve the reapportionment issue swiftly and decisively. Finding that the Constitution required a one person, one vote standard and reapportionment after each census accomplished that result.

A New Politics: From Baker to Today

With the hindsight of half a century, one can now see clearly that the most important and durable change set in motion by those rulings was the requirement that all state and federal legislative districts must be redrawn after every census to produce districts of approximately equal population.

The constitutional standards for court review of that process differ somewhat between federal and state legislative bodies, but the basic rules (reapportion after every census and draw equal population districts) are the same for the U.S. House of Representatives and the state legislatures. Despite a lot of litigation in the redistricting area since the 1960s, the Court has not wavered on those key points of constitutional interpretation.

All of this historical background helps make sense of the current mess in redistricting. By firmly insisting that the Constitution requires equal population districts regardless of most other factors, such as the kinds of people who lived in cities versus the countryside or the different economic interests located there, the Supreme Court redirected parties' and organized interest groups' efforts.

Instead of trying simply to resist redistricting entirely, or to promote it, parties and interest groups (the two were often closely related) began looking hard for ways to enhance their political power within the constraints imposed by equal population districts.

By the 1970s, increasingly sophisticated computer technology and mapping tools enabled state legislatures to produce districts that were of equal population but still gave one party or interest group the maximum possible number of safe seats.

Leaders of this new science of political demography were the Burton brothers (Dan and Phil) of California, two Democratic politicians who used ever more powerful computer software to craft congressional districts that disproportionately favored the Democrats.

This was accomplished by increasingly divorcing congressional district boundaries from "natural" community ones. Computers capable of manipulating very large quantities of detailed information about voting behavior at the precinct level enabled the Burtons to vary district lines so as to move blocks of voters to districts where they were needed most to maximize the Democrats' electoral advantage in congressional contests.

In the 1980s, with the ascendancy of the Reagan Republicans in the Sunbelt, GOP strategists began to do the same thing very successfully, and to extend that approach to state legislative districts. When the Democrats revived under Bill Clinton in the 1990s, an era of intense, national, two-party competition opened.

Much more effort was poured by both sides almost everywhere into redistricting schemes that maximized partisan and interest-group advantage by creating the maximum number of uncompetitive (i.e., safe) seats for incumbents of both of the country's two major political parties.

Republicans have done better in that contest since the 1980s, largely because the fastest growing parts of the country have been in the Sunbelt, where the GOP is now strongest.

Perhaps most importantly, as legislative bodies have become ever more polarized their ability to construct reasonable compromises reflecting the broad middle of public opinion decreased dramatically.

At first, the U.S. Supreme Court tried to regulate via constitutional interpretation how far one could go in this regard, before essentially throwing up its hands in a 2004 ruling known as Veith v. Jubilirer.

There, a deeply divided Court indicated that absent a redistricting scheme that seriously under-represented African-American residents' voting power, the Court would not intervene.

Changes in the Court's overall membership since 2004 do not suggest it will deviate much from the Veith ruling anytime soon, especially in northern states with heavily white populations such as Pennsylvania, where the Veith case arose. The Supreme Court might be willing to intervene more in states such as Texas that have big black and/or Latino populations, but one cannot be certain yet that the Court will deviate much from the reasoning of Veith in resolving redistricting lawsuits even in heavily multi-racial states.

The Redistricting Battles Today

Which brings us to our current moment.

What's new this time around is the greater degree of partisanship and, related to that, the greater volume of litigation. Ohio, almost always a bellwether state for national politics, is an instructive example.

As in many other states, the Republicans did so well in the low-turnout, 2010 off-year elections in Ohio as to make compromise with the Democrats in the redistricting process seem unnecessary. Emboldened by the GOP's solid majorities in both houses of the state legislature and control of the key statewide offices, Ohio Republicans set to work in 2011 to redistrict in such a way as to maximize their party's advantage.

There are, of course, different ways to do that.

What the Republicans tried to do is to create the maximum number of safe Republican seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Ohio General Assembly, and a minimum number of truly competitive seats. Such a slicing of the districts increases polarization because there are so few truly swing districts in the state.

The best way to do that in Ohio and across the country generally is to break up major metropolitan areas (where the Democrats are usually strongest) and combine pieces of them with exurban, small town and rural areas (where the Republicans are strongest).

Such an approach protects GOP incumbents (who don't want to spend down their campaign war chests fighting competitive fall campaigns against Democrats), but is at odds with Ohio's moderate political culture, which is partly the result of a fairly equal division of the statewide electorate between Democrats and Republicans, especially during high-turnout years. The GOP approach was, to be sure, simply an intensification of efforts that had gone on earlier, after the 2000 census.

The congressional districts that GOP leaders proposed last September were so partisan in their objectives and so completely divorced in most cases from natural community boundaries as to provoke staunch resistance from Ohio Democrats and a good many Independents. Without the numbers to resist in the legislature, opponents turned both to the courts and to an effort to place the GOP redistricting plan before the voters in the form of a referendum in November 2012.

The result for the following few months was a complete muddle. Republicans in the General Assembly back-pedaled, hoping to strike a deal with black Democrats from the big cities, thereby splitting the Democrats and protecting the bulk of the GOP redistricting scheme.

That approach did not bear fruit, and so the possibility of having to hold two different sets of primaries in 2012 loomed over the legislature. The first set of primaries would be held in March to choose presidential nominees for the two major parties and a second set in June to choose candidates for the U.S. House, because a revised plan for congressional seats seemed unlikely to be in time for the earlier primary.

That scenario was so expensive and unpopular that it moved the Republicans to compromise a little. At the same time, the Democrats found that the effort to gather signatures to force a referendum was proving to be a lot harder and more expensive than they had earlier thought it would be, which prompted them to back off.

On December 14, 2011 the two sides announced a compromise consisting of slightly revised congressional district maps. The new proposed districts were a bit less unnatural in terms of existing community boundaries than the earlier ones had been.

Even so, hard-headed observers predicted that twelve of Ohio's sixteen congressional districts would be safe Republican seats, and that most of the rest would be safe Democratic seats, which will contribute substantially to polarization in the state's congressional delegation. The only effort to address such a schism was an agreement between the Republicans and the Democrats in the Ohio General Assembly to create a new bipartisan task force to study how to improve the process next time.

Resolving disputes over new maps for the Ohio General Assembly has moved at a slower pace, but the overall pattern is the same as it was for the congressional districts. The proposed general assembly district maps tend to maximize the number of safe seats for the Republicans by fragmenting major metropolitan areas where the Democrats are strongest.

Opponents filed suit in the Ohio Supreme Court on January 4, 2012 claiming that the proposed districts violate the Ohio Constitution's requirement that seats in the state legislature respect existing community boundaries. While the Court may well take the case, finding in favor of the Democrats appears highly unlikely.

Only two months remain until Ohio's 2012 primaries will be held in the newly proposed districts. A Court ruling that those lines are unconstitutional would therefore disrupt the 2012 electoral process. Thus, the net result for the next decade will likely be congressional and General Assembly districts that further enhance the power of small towns and rural areas, and of the Ohio Republican party.

Complicating matters even more is the fact that redistricting schemes intended to enhance the power of small towns and rural areas can meet other objectives. For example, enhancing the political power of rural areas arguably makes sense in states where agriculture is important to the state's economy but employs relatively few people. That is certainly the case in Ohio, where in recent years agriculture has been the single biggest part of the state's economy.

Enhancing the power of small towns and rural areas can also serve other objectives favored by many voters, in the realm of social legislation for example. Those places tend to be the most morally traditional. Enhancing their political power can help states and Congress pass and enforce certain kinds of laws protective of small children, such as restrictions on drinking, gambling, pornography, and prostitution.

Of course, not everything about small towns' and rural areas' political culture tends to produce child-friendly results. For example, support for easy gun ownership is strongest there, and that can be profoundly child- and family-unfriendly in a major metropolitan context. One can argue, however, that enhancing the voting power of the most morally traditional areas of the state and country on balance is more protective of small children, and many of the most moderate people in both of the two major political parties quietly agree that is the case.

The Supreme Court's willingness in recent years to allow major metropolitan areas to enact strict gun control legislation, as long as it does not constitute a flat ban on gun ownership, has also contributed to that sense. So, too, has the Court's continued support for reproductive rights, given that the most morally traditional areas of the country are often outside the mainstream of American public opinion on reproductive rights issues.

And then there is the complication in the North and West caused by where most members of racial minority groups live, the only demographic category the Vieth decision declared protected in the redistricting process. Unlike the South, where blacks live in large numbers in rural areas and small towns as well as cities, the minority presence in the northern and western states is mostly within major metropolitan areas.

Thus, redistricting schemes there that aim to enhance the power of small towns and rural areas, even for arguably legitimate reasons, may well have the effect of diluting the voting power of racial minority groups, something that is constitutionally highly suspect.

This, by the way, helps explain why Ohio Republicans were interested in striking a deal with black Democrats with respect to redistricting. If the resulting districts maximized GOP and black Democratic advantage, they seemed likely to survive court challenges and, on balance, to strengthen the Republicans as such.

The Way Forward

What, if anything, can be done about the mess in redistricting, which is ever less acceptable to the increasingly active middle of the electorate in Ohio and nationally?

The U.S. Supreme Court's message lately has been to fix this through the electoral process, on the theory that swing voters will punish parties that brazenly pursue partisan advantage through redistricting. That view has a certain merit, but it is hobbled by the pattern of voting nationally that emerged in the 1990s.

Since 1992, voting in presidential years has been fairly high by modern historical standards, but in off-year elections, turnout has usually been quite low. The reasons for that situation are many, but among the most important is the inability of Democrats to mobilize their voters in large numbers during less exciting, off-year contests.

The decline of private-sector unions since the mid-1960s across the North has contributed significantly to that situation, because the Democrats since the 1930s have relied heavily on unions to turn out their voters. And so when state legislatures that will redistrict after the census are elected in off-years, as was the case in 2010, the electoral results are disproportionately Republican when compared with the outcome a high-turnout, presidential year would have produced.

Given that situation, reformers have split on the best way to address the underlying problem. Some argue for a bigger role for the courts, in effect seeking to overturn Vieth v. Jubilirer. Others argue that what's needed is to strengthen the Democratic Party and unions so that they can compete more effectively in off-year elections.

Yet another group of reformers favors more use of the statewide referendum process—in states that have such a thing—to defeat brazenly partisan redistricting schemes. A fourth focuses on trying to create a less partisan body to propose new maps. The most likely result is a combination of all four approaches to reform.

Still unclear, however, is the relative contributions to be made by them. Will the emphasis mostly be on courts? On strengthening the Democratic Party and unions? On the referendum process? On creating a less partisan body to draw maps? Will some combination of these factors do most of the heavy lifting here, and if so, which one? Or will all of these contribute more or less equally?

For the moment, we will continue to fight over the geography of our democracy.

[The author would like to extend special thanks to Paul Beck and Ned Foley.]

Stephen Ansolabehere and James M. Snyder, Jr. The End of Inequality: One Person, One Vote and the Transformation of American Politics (Norton, 2008).

Robert A. Dahl, How Democratic is the United States Constitution? (Yale, 2003).

James A. Stimson, Tides of Consent: How Public Opinion Shapes American Politics (Cambridge, 2004).

Gary Cox and Jonathan Katz, Elbridge Gerry's Salamander (Cambridge, 2002).

Robert Erikson, Gerald Wright, and John P. MacIver, Statehouse Democracy (Cambridge, 1993).

Kenneth Shepsle and Mark Bonchek, Analyzing Politics (Norton, 1996).

Bernard Grofman, ed., Is There a Better Way to Redistrict? (Agathon, 1996).

Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman, eds., Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965-1990 (Princeton, 1994).

David Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (Yale, 2004).

Morris Fiorina, Congress: Keystone of the Washington Establishment, 2nd ed. (Yale, 1989).