A common response to the COVID-19 epidemic worldwide has been rigorous testing regimes that identify sick and asymptomatic carriers of the virus. China’s “health code apps” are already an everyday tool to track and regulate movement.

Employees operating a testing center at the Walmart Supercenter in Elizabethville, PA, August, 2020.

Although experts have cautioned there is much we still do not know about immunity conferred by sickness, countries such as Germany are testing the feasibility of personal safety certifications based on measurable novel coronavirus antibodies.

It seems clear that verifying personal COVID-19 status is becoming part of our near-term future. And a key part of this will be identifying and managing not only those infected but those who do not pose a disease danger.

Professional sports leagues have created elaborate “bubbles.” School districts and universities have moved to implement induction procedures, involving sequential quarantine stages and periodic lab tests to maintain virus-free cohorts.

The certification and tracking of health—as opposed to persons with sickness or infection—is another expression of the urge in the midst this pandemic to “return to normal.” Showing an updated health passport may soon be required at international airports, workplaces, nursing homes, and other places.

But, as with most seemingly novel practices, this one has a long and complicated history. Health passes will aid in constructing a “new normal” that nonetheless retains echoes of the past.

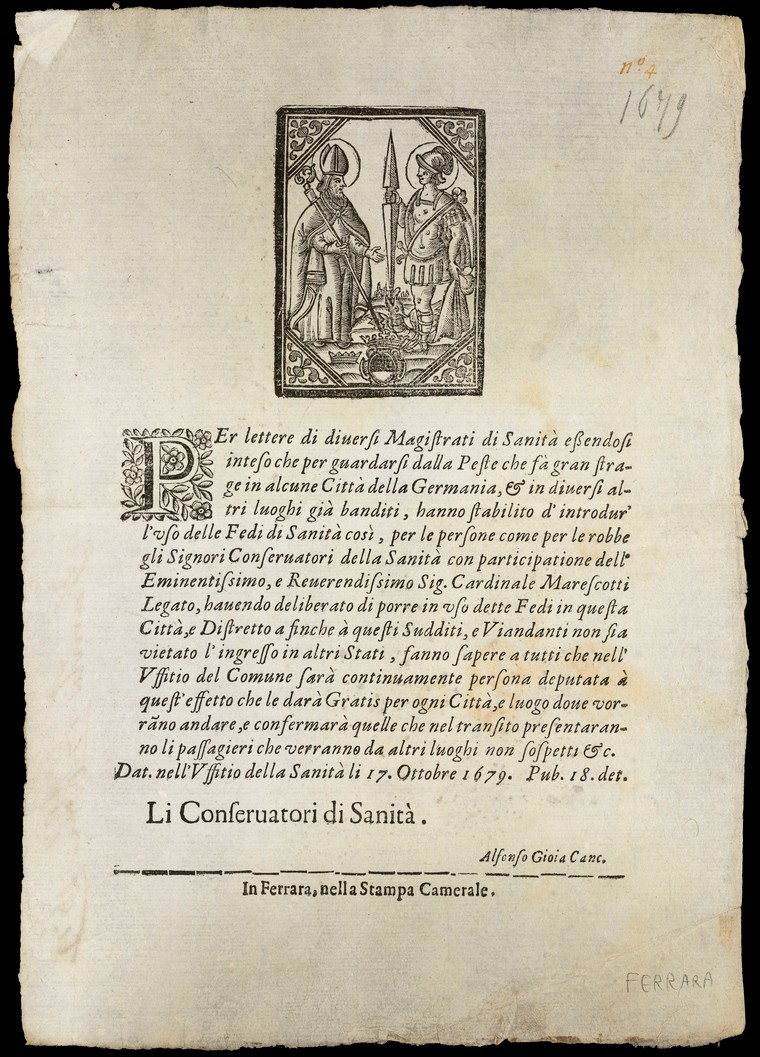

In the decades following the Black Death in the mid-1300s, city-states such as Milan and Venice put in place systems to diagnose and isolate plague victims as well as monitor contacts. Physicians later issued “health passes” attesting that a patient did not exhibit plague symptoms.

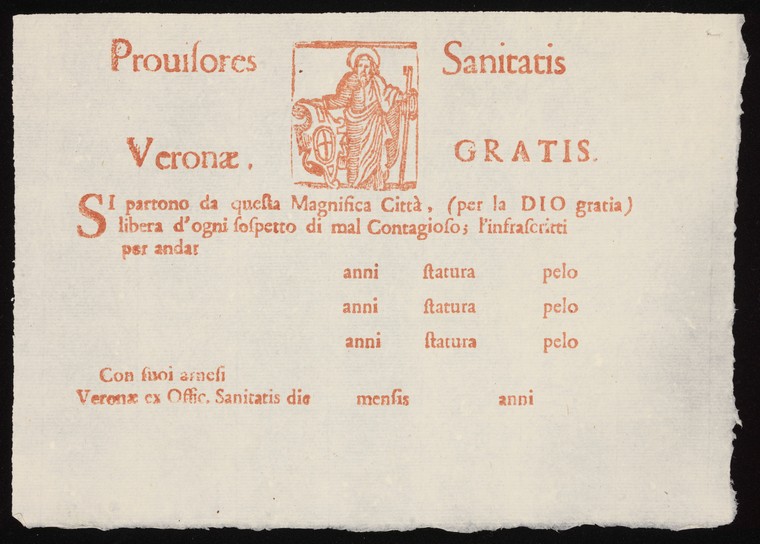

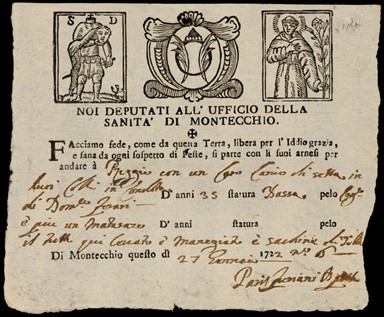

Cities and towns periodically imposed travel restrictions during disease outbreaks but also regularly issued exemptions on printed forms. These usually featured a royal crest or other insignia testifying that the person named in the document either was not visibly sick or was arriving from a town not then experiencing an outbreak.

Health passes became common in the 1500s, particularly in Italy.

In order to bolster their authenticity and counter allegations that they were used as instruments of extortion, Italian officials typically had it printed at the top that the form was issued free of charge—underscoring that the entire system of issuing and accepting health passes was based as much on trust and royal authority as on medical certainty.

During the great plague of London in 1665 the Lord Mayor himself handed out certificates of health to well-connected persons wishing to flee the city.

These early modern epidemic passports often had little to do with pledging the healthiness of the bearer. Rather, they simply marked persons exempt from government controls and cleared a path for movement.

Documents that attested to a person’s relative health risk were nonetheless central to the quarantine process that served as a regular feature of Mediterranean trade networks for centuries. The first Venetian port quarantine in 1377 imposed a 40-day waiting period for arriving ships, during which time the crew and passengers would be watched carefully for signs of plague.

Over time, similar rules were imposed and refined at practically all major trading nodes. Many cities eventually just required captains to show a “bill of health” signed by the health officer of the previous port of call stating that plague was not currently present.

A “clean” bill meant the ship could perform short quarantine or skip it altogether, while a “foul” bill would require the full, onerous procedure—perhaps including the complete disembarking of people and goods at the port lazaretto, where they would be aired out and observed for 28 days.

This type of quarantine procedure introduced new problems of verification and authenticity. In fact, the health pass parallels the development of the modern “passport”—a document to fix and confirm the identity of a person travelling in foreign lands, perhaps first issued for that purpose by the English crown in the early 1400s.

This quintessential artifact of the bureaucratic state arose from the desire for health surveillance as much as political surveillance, with one realm often overlapping with the other.

Passports appeared alongside the emergence of national borders. While today we tend to think of it as a device that opens doors, the passport has always more closely been linked to the process of policing entryways and blocking passage. New concepts of sovereignty required control over bodily mobility, which was perfectly analogous (in theory at least) to the control over disease mobility.

In this way, the health passes and political passports of the early modern period linked the problem of movement with the problem of identity.

Seeking to govern things previously ungoverned, they gave rise to a wide range of licenses and permits that have the aim of affixing the identity of the bearer, sustaining certain individual qualities, and authorizing certain activities and movements.

Documents were susceptible to forgery and counterfeit, however, and so attestation of health assurance was not thought to reside in passes themselves. Presenting one was more like “giving notice,” and not intended to be a guarantee of non-infectiousness.

Persons holding health passes were not made exempt from further scrutiny. Just the opposite: they actually shouldered additional burdens of demonstrating their health and enmeshed themselves in new layers of reconnaissance.

We should probably keep this history in mind when considering coronavirus passports today, and be especially be cautious of claims they could “help restore freedom of movement.”

This may be true in only a very particular sense. Extending confirmation of health status to foreign travel, commercial spaces, and work environments would also undeniably magnify the regulation of movement—all the more so when built on 21st-century identification technologies that increasingly merge body and certificate.

The next step may be one where fingerprint, facial or retinal recognition is used to unlock and verify health certificate details, as may be piloted in Britain.

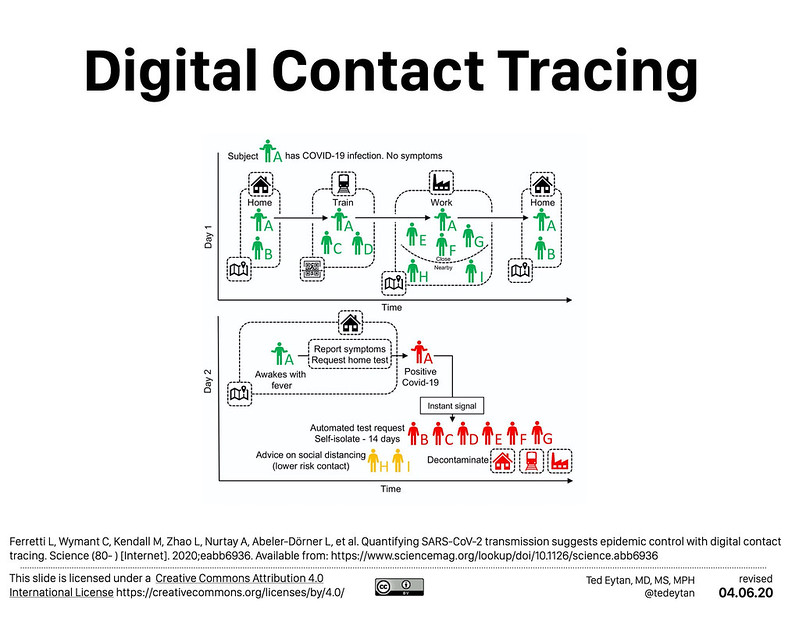

Digital health documents would presumably be integrated with the contact-tracing technology being rolled out whose developers have struggled to balance anonymity with their goals of predictive algorithmic analysis.

Pass holders might find themselves in a similar surveillance position as those asked to wear virus-tracking wristbands (soon to be tested in Singapore). They would need to stay under constant reconnaissance to see if the tools were having their intended effect.

In China, the QR codes used to monitor individuals’ COVID status and to grant personalized access are expected eventually to be fully integrated with the country’s “social credit system,” meaning one’s health score will be largely indistinguishable from political scoring.

In principle, health passports would help restore movement. But it would be movement encompassed within steadily proliferating checkpoints, confirmations, and valuations.

Given the appalling social disparities in the United States, any ostensibly impartial system of health passports would almost invariably result in additional inequities. 58% of Americans do not possess an international passport; 15% lack a driver’s license.

The uptake rate for health certifications may be similarly low, especially if individuals are expected to cover costs for multiple tests to keep the passport current and if insurance coverage for testing remains contingent and uncertain.

One uncomfortable probability is that COVID health passes, not unlike their historical predecessors, will buttress already-very-lopsided systems of power and privilege. Large employers may find it worthwhile to pay for workforce screenings—not for the public good but for private gain.

The NBA for instance instituted sophisticated “bubbles” for elite players and staff at Disney World at the same time that hard-pressed health agencies struggle to provide enough public testing.

Meanwhile, low-wage “essential workers” everywhere have been provided with no protections whatsoever, with many of their employers seeking and receiving statutory immunity to liability. Furthermore, there have been persistent racial disparities in access to COVID tests.

A view into a pizza shop during the coronavirus pandemic in NYC, April, 2020.

Given the patchwork nature of the US health system and pandemic response, a high-stakes Covid certification regime would almost certainly magnify these sorts of resource inequities.

Furthermore, and reflective of the systemic impact of implicit bias, the policing of social distance rules has had a harsher negative impact on Black communities in America. It is not difficult to conceive that those communities already informally subject to a higher standard of documentation and surveillance will be disproportionately harassed by requirements for “health papers.”

Early-modern health passes reflected that society’s social distinctions and privileges. Could COVID passports today end up mirroring the unresolved impacts of racist “stop and frisk” policies and the xenophobic rhetoric of “extreme vetting?”

Some people might be permitted to return to “normal,” while many others would find their lives more precarious.

There are major differences between health passports for traveling internationally and ones for maintaining a foothold in the labor market. However, a requirement for either could become an essential ticket to comfort and success attainable only by the fortunate few—a type of pandemic privilege that has occurred many times in history.