For more than two decades, the Catholic Church has been reeling from sexual abuse scandals. Stories of predatory priests have emerged around the world. While some have attributed the abuses to problems in contemporary society, this month historian Wietse de Boer takes a much deeper look. He argues that the way the Church has responded to these outrages has its roots 500 years ago when the Catholic Church faced its first major crisis of sexual abuse.

The institution of the Catholic Church finds itself in a period of extraordinary crisis.

An August 2018 grand jury report on clerical sex abuse in six Pennsylvania dioceses gave a detailed, often graphic account of decades of criminal offenses against minors by Catholic priests. Other states have since launched their own investigations. Evidence that church superiors—bishops, archbishops, and even popes—failed to address abuses effectively has only amplified the outrage.

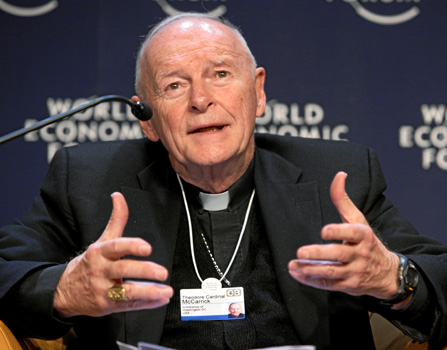

Some church leaders were found to have engaged in such acts themselves. A leading figure of the Roman Catholic hierarchy, the former cardinal and archbishop of Washington, Theodore E. McCarrick, had a long and widely rumored history of misconduct against priests, seminarians, and several minors. Pope Francis ordered McCarrick to observe “a life of prayer and penance in seclusion” before accepting his resignation in July 2018. In an extraordinary measure, he was removed from the priesthood in February 2019.

All of these tragedies are tinged with a sense of déjà vu. Similar patterns of abuse have been front-page news in the United States since an explosive 2002 investigation by the Boston Globe (subject of the 2015 Academy Award-winning film Spotlight), but the problem was known decades earlier.

In the United States, the first reports appeared in the mid-1980s. In Ireland and Austria, there were notorious cases in the mid-1990s. The case of disgraced priest Brendan Smyth even contributed to the fall of the Irish government in 1994.

The poster for the 2015 film Spotlight (left). The logo for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (right).

A so-called zero tolerance policy adopted by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2002 has done little to halt the controversy. It may have reduced the prevalence of abuse, but it has not stemmed the tide of accusations. Outside the United States, too, investigations have roiled Church and society in numerous other countries, from Australia to Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Germany, and the Netherlands.

In February 2019, Pope Francis spoke out against what he described as the “sexual slavery” that nuns all-too-frequently suffered at the hands of Catholic priests.

These are extraordinary times, to be sure, but the Catholic Church has been roiled by sexual scandals in the past.

Proceedings of the Second Vatican Council in 1963.

The intractability and pervasiveness of the problem suggest that it is deeply rooted in the Church’s own history. In fact, several explanations proffered in heated debates about the current crisis—especially among Catholics—are wrapped in historical judgments, particularly about the development of the Roman Catholic Church since the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).

Some Church critics point to an ossified church structure and antiquated norms of sex and gender, including clerical celibacy and a male priesthood. Others denounce the subversion of the clergy by an assumed gay subculture or, more broadly, changing sexual mores since the 1960s.

Occasionally, commentators have referred to an insular institutional culture going back to the 19th century—the time when Pope Pius IX repositioned the Church against modernity in the aftermath of the liberal revolutions of 1848 in Europe.

Pope Pius IX with the clergy members of his Papal Court around 1878.

Whatever the merits of these arguments, an examination of a more distant past may provide another, under-appreciated perspective on the phenomenon we are witnessing now and offer clues to its tenacity. In a general sense, the sexuality of priests has been a thorny issue for much of the history of Christianity.

Yet today’s crisis of the Catholic Church, which commentators have called the gravest since the Reformation, may have its most significant precedent precisely in that era. In fact, the 16th-century Church was rocked by a sexual abuse scandal of its own. Its responses then may still be helpful for understanding the crisis of today.

Confessing Sins or Committing Them?

Writing in the early 16th century, the Dutch scholar Erasmus already lamented that the faithful “often fall into the hands of priests who, under the pretense of confession, commit acts which are not fit to be mentioned.”

He was not alone. The suspicion that all too often priests abused or seduced their flock—usually young women—was common in the late Middle Ages. When the Reformation erupted, it became fodder for Protestant critics of the Catholic Church.

Their preferred target was the sacrament of confession. The idea was not far-fetched. In Renaissance cities and towns confession was among the few accepted occasions for respectable women to meet unsupervised with men outside their families, whether their parish priests or the vast army of monks (Franciscans, Augustinians, Dominicans, and others) who served as preachers and confessors.

As Erasmus realized, such confidential encounters made fertile ground for improper relations.

These concerns were exacerbated, some historians have argued, by a contemporary shift in confession. In earlier centuries, most lay people partook in this sacrament mainly during the annual cycle of Lenten reconciliations in preparation for Easter. In this context, confession meant above all to own up to “social” sins like avarice, anger, and pride, and to address their deleterious consequences for the Christian community.

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, a different mode of confession gained ground among the devout, particularly among women. For them, the practice turned into a regular exchange with a priest, who took on the role of confidant and spiritual adviser. Such exchanges often turned to questions of the heart, especially those of a sexual nature.

A fresco in the Church of the Incoronata in Naples, Italy painted between 1352 and 1354, entitled "Confession and Penance with Devil" (left). An open air confessional from the Netherlands in 1740 (right).

Official guidelines sought to curtail the risk that these conversations might cross boundaries of propriety. Rules stipulated that confessors and female penitents should meet in church in daylight and avoid eye contact. They were also to use a concise, technical vocabulary to discuss sexual matters. Have you committed adultery? Have you engaged in an unnatural act? Did intercourse involve the wrong vessel? Have you corrupted your eyes, ears, smell, or touch in lascivious ways?

We have little reliable information about the incidence of sexual abuse that arose during confessions, but such cases were certainly not uncommon. As the Reformation unfolded, the issue provoked major concern among leaders of the Roman Church.

While some dismissed the accusations and suspicions as gossip and slander, even they acknowledged the resulting damage to the image of the Church. Nor was this concern limited to churchmen: families and governments cared as much or more about the honor of wives and daughters.

Confessional in the parish church of Abbadia Lariana in Lombardy, Italy.

One outcome was the development of the confessional. This idiosyncratic piece of church furniture was deliberately designed to forestall improper contacts between priest and confessant, especially when female.

Wooden panels between the two people prevented physical contact. A grill was installed to block the lures of eyesight while allowing speech. And rather than promoting privacy (as is sometimes thought), the confessional was originally designed to be open on all sides and installed in a public place to facilitate social control by watchful eyes.

Developed in Italy during the middle decades of the 16th century, it became standard equipment prescribed in dioceses across the Catholic world until the twentieth century. It is still used in parts of the world today.

A confessional in India (left). Temporary confessional booths set up in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil during Pope Francis’s visit in 2013 (right).

Bringing in the Inquisition

Another approach to contain the sexual crisis was legal. The Counter-Reformation Church began to sue priests who exploited confession to make sexual advances.

By the early 17th century (and possibly earlier), ecclesiastical legalese was enriched with a new euphemism to designate the offense: “solicitation of unseemly things” (sollicitatio ad turpia). As a form of sacrilege against the sacrament of penance and potentially a sign of heresy, prosecution for solicitation was assigned to the Inquisition.

The Archbishop of Granada, Pedro Guerrero, around 1616 (left). Pope Paul IV, Bishop of Rome from 1555 to 1559 (right).

This legal, institutional response was a long time in the making. Its direct origin lies in Spain in 1558, when a female penitent of Granada disclosed to a Jesuit that her confessor was harassing her.

What to do with this information? It was a delicate question. For a woman to denounce the offending priest carried serious risks for her honor and even her life.

Consulted on the issue, the Jesuit superiors and Pedro Guerrero, archbishop of Granada, decided that another confessor could report the case on the woman’s behalf. That position was strongly contested by members of other religious orders, who objected to the inevitable breach of the secrecy of confession.

Within months, however, Pope Paul IV endorsed the original plan by granting the inquisitor of Granada the power to prosecute suspects of solicitation in the confessional. This new inquisitorial role was extended by papal bull to all of Spain in 1561, subsequently to Portugal, and in 1622 to the entire Church.

The 1622 bull illustrates the alarm with which the crisis was being perceived. Pope Gregory XV denounced solicitation as an “impious and heinous crime” and a “plague” infecting those whose job it was to heal others. Confessors who fell victim to the “most pernicious traps of the devil” were transformed from “heavenly doctor[s]” into “infernal sorcerer[s].”

The effectiveness of the new policies remains unclear, yet surviving Inquisition archives across the Catholic world still contain records of thousands of solicitation cases against priests.

A depiction of the Sacrament of Penance from around 1800.

They range from Catholic Europe—in areas where the Inquisition was active—to its overseas foundations in the Americas, India, and elsewhere. They span the late 16th to the late 18th or early 19th centuries, when the major Inquisition offices were closed. (The central Holy Office of the Roman Inquisition continued to function into the 20th century, when it was reformed and renamed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which is still in operation.)

What emerges from these records is certainly the kind of unequal power relationships that define modern instances of sexual harassment. The “power of the keys”—the power to absolve from sin—invested confessors with tremendous religious and judicial authority.

This placed women subjected to unwanted attentions in an agonizing situation. Many saw little choice but to indulge such advances, at least for some time, or even to establish long-term relations. The dangers of exposure frequently led them to conceal their experiences even from their family. In other cases, it was precisely the outrage of relatives—particularly among social elites—that led to Inquisition trials.

An 1854 depiction of a woman confessing to a priest.

More often, however, the women themselves developed strategies to resist or evade their pursuers. Sometimes they appealed to their honor to get the confessor to back down; at other times, they reduced the frequency of their confessions. When they could, they sought another priest to conduct the sacrament. If word got out through the grapevine, a priest could gain the reputation of a predator and be avoided. In some convents, nuns organized to report their confessors to the authorities.

While numerous cases are known, many questions remain. What proportion of sexual offenses by the clergy led to denunciations? How much is captured by the surviving documentation? How common was solicitation outside the confessional? How frequent were the offenses against boys or men? Last but not least, what happened to priests found guilty?

The Confession, a 1750 painting by Venetian painter Pietro Longhi (left). An 1838 painting by Giuseppe Molteni of a woman kneeling at a confessional (right).

In a general sense, the Inquisition process was “penitential” in nature. Its goal was to get suspects to acknowledge, confess, and abjure their wrongdoing, and have them undertake forms of penance to induce a spiritual transformation. Specific penalties could also include removal from the office of confessor, exile, monastic confinement, and very exceptionally, being turned over to civil authorities.

But the effective enforcement and outcomes of such punishments remain unclear. How often, for instance, did convicted priests return to pastoral care?

We don’t have full answers to such questions.

“Scandal” and “Shame”

We can, however, discuss the Church’s response to the early-modern abuse crisis in more general terms that remain relevant today.

First, prosecutions for solicitation remained largely internal. Misconduct of this kind fell under canon law—a code coexisting with (and in many cases bypassing) the secular legal systems governing early-modern cities, states, and empires. This ecclesiastical law had a remarkably broad scope, including offenses involving the clergy, but was structured differently from secular justice.

It had two areas of jurisdiction. The so-called internal forum was the sphere of the conscience, overseen by confessors and spiritual directors.

At its center was the confession of sins, protected by the obligation of confidentiality—the seal of confession. That fundamental trait created the conditions in which solicitation could occur and which made it hard to address. This was compounded, of course, by the offending priest’s power to absolve his victim of any qualms she (or he) might have about the situation.

The external forum was the legal sphere that handled offenses under the jurisdiction of church courts, including papal and episcopal courts and the Inquisition.

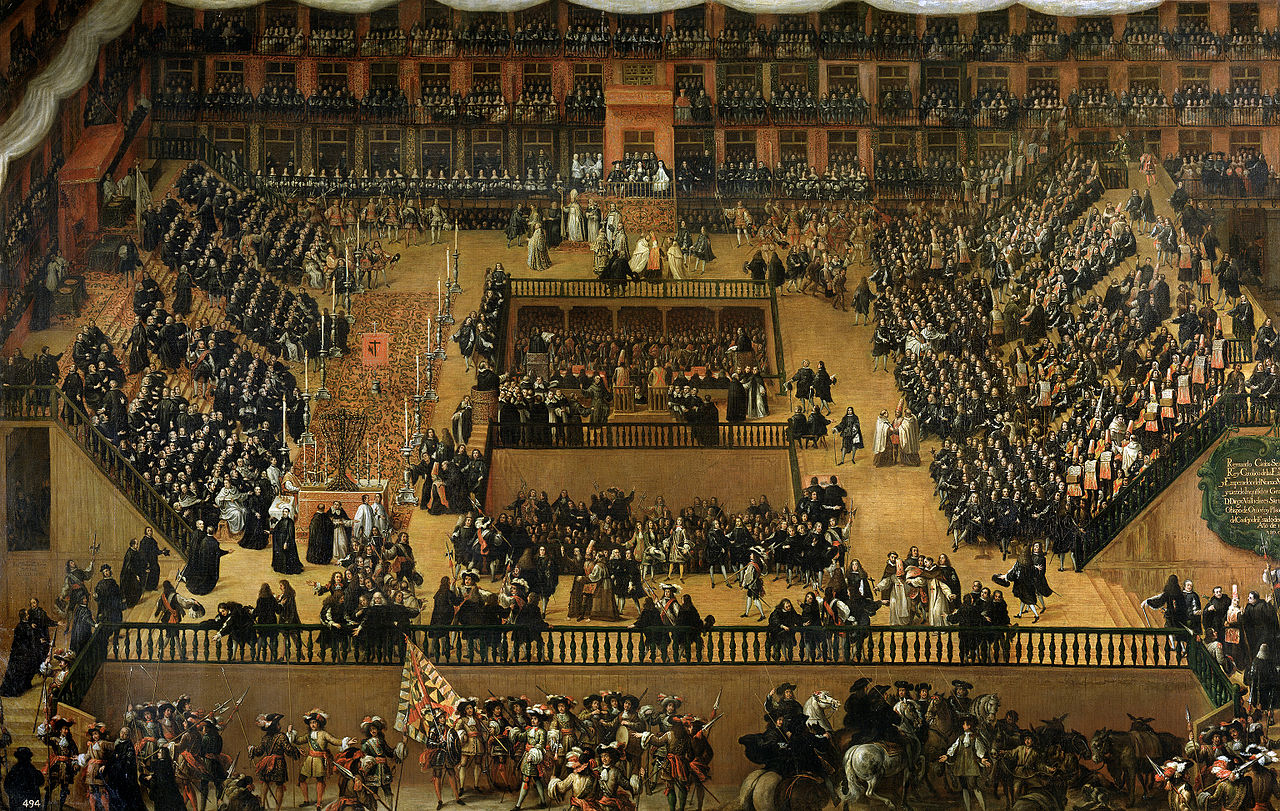

A 1683 Francisco Rizi painting of an Auto de Fe in Plaza Mayor, Madrid in 1680.

Here, too, secrecy was generally the norm. Under the Spanish Inquisition, trial proceedings were confidential, but convicted heretics were publicly named and shamed in a ceremony called Auto de Fe. Solicitation cases formed an exception: convicted confessors were exposed, at most, only to a select group of fellow priests.

Thus secrecy was considered vital when clerical misconduct might stain the reputation of the Church—a deep concern amidst the fierce religious battles of the post-Reformation era. The Council of Trent (1545-63)—the major reform gathering convened by the Church to address the Protestant threat—had discussed the issue only behind closed doors and never adopted a solution.

A depiction of the Council of Trent (1545-1563).

To be sure, the church fathers expressed concern about priests who dared “tempt the chastity of women even during confession.” But the subject required a cautious approach, “in order not to reveal our shame.” A draft proposal from the Council—though never approved—required that all confessions of women take place in open, visible places. Its stated aim was only “to put an end to the scandals of the petty and the insinuations of the vicious.”

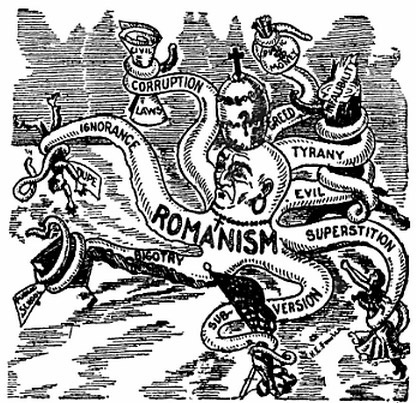

In an age that ended the Church’s de facto monopoly in much of Europe, scandal thus provoked a deep-seated fear, which has become part of its institutional DNA. The word “scandal” itself was a technical term, and a subject in the growing field of moral theology. According to one contemporary theologian, scandal redoubled a sin by making it public, thus exposing others to its powers of contamination.

During the Enlightenment era, allegations of sexual abuse grew to new levels of intensity. Some priests became critics themselves. The Spaniard Antonio Gavin fled to England around 1713 and went on to publish an incendiary account of confession in The Master Key of Popery. Later in the century, José Blanco White and Juan Antonio Llorente—other ex-priests turned publicists—joined the attack on solicitation, fuelling broader polemics against the Inquisition and the Catholic Church as a whole.

The Past as Prologue?

All this may seem ancient history now. And it is obvious that the current crisis displays major differences from what we know about its distant predecessor. Specifically, the current crisis centers around the abuse of minors, frequently boys; and the exposed practices go well beyond confession.

The broader circumstances have changed more dramatically. The role of Catholic canon law and the voice of the Church generally have been much weakened in modern pluralistic states. Moreover, the revelations of the last decades, and the global repercussions in and outside the Church, would have been unthinkable outside democratic societies with a free press and, now, the internet.

Yet the echoes from the pre-modern era are significant, sometimes uncannily so.

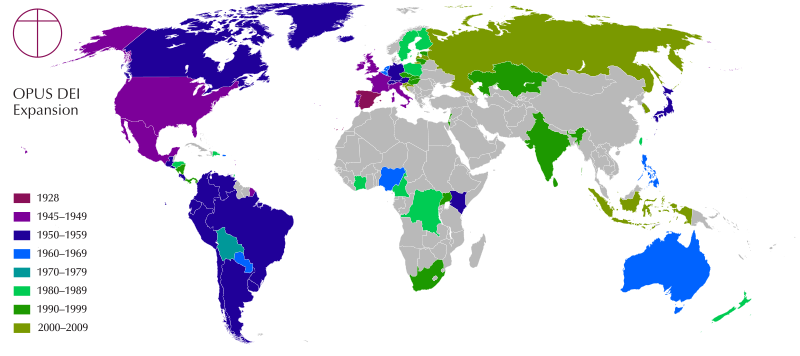

A map showing the expansion of Opus Dei.

In 2005, C. John McCloskey, a prominent member of the conservative Catholic organization Opus Dei, was found responsible for sexual misconduct against women who confessed with him. As part of a financial settlement, The Washington Post has reported, he was ordered “to only give spiritual direction of women in the traditional confessional—meaning separated physically from them.” It was an old solution to an old problem.

A more general form of continuity is found in the Church’s long-standing preference to handle abuse allegations internally, within the parameters of its moral and legal systems, rather than turning them over to civil authorities. Priests found guilty were typically condemned to moral censure, a life of prayer and penance, psychological treatment, or reassignment rather than criminal prosecution.

The framing of the problem in terms of sin and redemption is evident in Pope John Paul II’s earliest responses to the American child abuse scandal that erupted in 2002. Addressing the Catholic priesthood, he referred to the “sins of some of our brothers who have betrayed the grace of Ordination in succumbing even to the most grievous forms of the mysterium iniquitatis [the mystery of evil] at work in the world.”

In a subsequent speech to U.S. cardinals, he placed his hope in “the power of Christian conversion” of perpetrators instead of prioritizing the protection of victims.

The pope’s words also evinced a clerical mistrust of the “world,” further expressed in the ancient concern about scandal that runs through his and other church officials’ statements. “Grave scandal is caused,” John Paul noted in 2002, “with the result that a dark shadow of suspicion is cast over all the other fine priests.”

Recently, confronted with a new investigation by the Attorney General of Illinois, Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield sought to justify this attitude, but also acknowledged its harmful consequences: “A virtuous intent to protect the faithful from scandal unfortunately prevented the transparency and awareness that has helped us confront this problem more directly over the past fifteen years.”

This admission, even as it confirms old habits, may also be read as a sign that cracks have appeared in an entrenched institutional culture.

Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò with President Barack Obama in 2013.

More strikingly, the sense of rupture leaps off the pages of a notorious open letter of August 22, 2018 by Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, a former apostolic nuncio (ambassador) to the United States. His “testimony” blames a Who’s Who of church officials, including prominent Curia members and the current pope, for the Church’s inaction and complicity in the abuse crisis.

The attack centers on the transgressions of Cardinal McCarrick, questions a church organization that did not prevent his ascent to its highest ranks, and culminates in an unprecedented call on Pope Francis to step down.

The letter has further drawn attention for its position in today’s Catholic culture wars. In a no-holds-barred invective, Viganò exposes presumed networks of gay clergy and church leaders whom he holds largely responsible for causing the abuse, facilitating it, and covering it up.

Yet the document is equally interesting as a gauge of the deeper history we have discussed. Here the verdict is complex. On the one hand, the text is replete with the dark moralism of Counter-Reformation rhetoric. “[T]he face of the Bride of Christ ... is disfigured by so many abominable crimes.” We must “free the Church from the fetid swamp into which she has fallen.”

Likewise, the ancient “penitential” spirit of church discipline still reverberates in Viganò’s text: “A time of conversion and penance must be proclaimed. The virtue of chastity must be recovered.” This is the language of the confessional and the pulpit, much less the (secular) courtroom. It is the language of an institution that calls for contrition and moral turnaround, but also offers mercy.

In the case of abusive priests, this kind of mercy appears to have been dispensed too liberally. Viganò is clearly exasperated by this spirit of forgiveness—a frustration that itself has a long history within the Church.

On the other hand, his “testimony” breaks new ground by openly confronting the culture of secrecy embedded in the traditions of church administration. Viganò does not hesitate to speak of omertà—a code of silence surrounding criminal activity—and remind his readers of the term’s origin in mafia culture.

He blames a gay subculture among the clergy for the corruption of the Church, noting: “These homosexual networks ... act under the concealment of secrecy and lies with the power of octopus tentacles, and strangle innocent victims and priestly vocations, and are strangling the entire Church.”

This Vatican insider thus feels compelled to break a longstanding taboo. Whereas, by his own account, he had warned his superiors in 2006 to intervene in the McCarrick case, “before the scandal had broken out in the press,” he now proclaims publicly that “[t]he faithful ... have every right to know who knew, and who covered up his grave misdeeds.”

Viganò’s attack has provoked, along with expressions of support, a host of condemnations, including a stern and unusually public rebuke from Cardinal Marc Ouellet, prefect of the Vatican Congregation for Bishops.

In an open letter, Ouellet denounced the ex-nuncio’s “open and scandalous rebellion” and called on him to “repent” and return to obedience to the papacy. Viganò retorted with further “testimony.”

These bitter recriminations, while still couched in traditional rhetoric, signal better than anything else how the sexual abuse crisis has brought about a marked departure from ingrained institutional habits in the church hierarchy. Under the glare of public attention and amidst an internal culture war, it has become accountable to the world.

Read more on Christianity from Origins: The Changing Face of Global Christianity; Protestant Preaching after the Age of Graham; Baptized in the Jordan; Martin Luther and the Reformation; and the Catholic Church and Copernicus

Listen to History Talk: The People's Pope and the Changing Face of Catholicism; Secrecy and Celibacy: The Catholic Church and Sexual Abuse

Juan Antonio Alejandre, El veneno de Dios. La Inquisición de Sevilla ante el delito de solicitación en confesión (Madrid, 1994).

Wietse de Boer, The Conquest of the Soul: Confession, Discipline, and Public Order in Counter-Reformation Milan (Leiden-Boston, 2001).

Stephen Haliczer, Sexuality in the Confessional: A Sacrament Profaned(New York, 1996).

Henry Charles Lea, A History of Auricular Confession and Indulgences in the Latin Church, 3 vols. (Philadelphia, 1896).

Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, 4 vols.(New York, 1906-1907), esp. vol. IV, chapter 6.

Patrick O’Banion, The Sacrament of Penance and Religious Life in Golden Age Spain (University Park, PA, 2012).

Adriano Prosperi, Tribunali della coscienza. Inquisitori, confessori, missionari (Turin, 1996).

Adelina Sarrión Mora, Sexualidad y confesión: la solicitación ante el Tribunal del Santo Oficio (siglos XVI-XIX)(Madrid, 1994).