Just how has American society mobilized for a sense of common purpose in the past? And why have we seemed to lose that sense of common purpose today in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and the struggles against racism and police violence?

At different points, particularly as the United States has gone to war, it has been vitally important to have a consensus holding the country together.

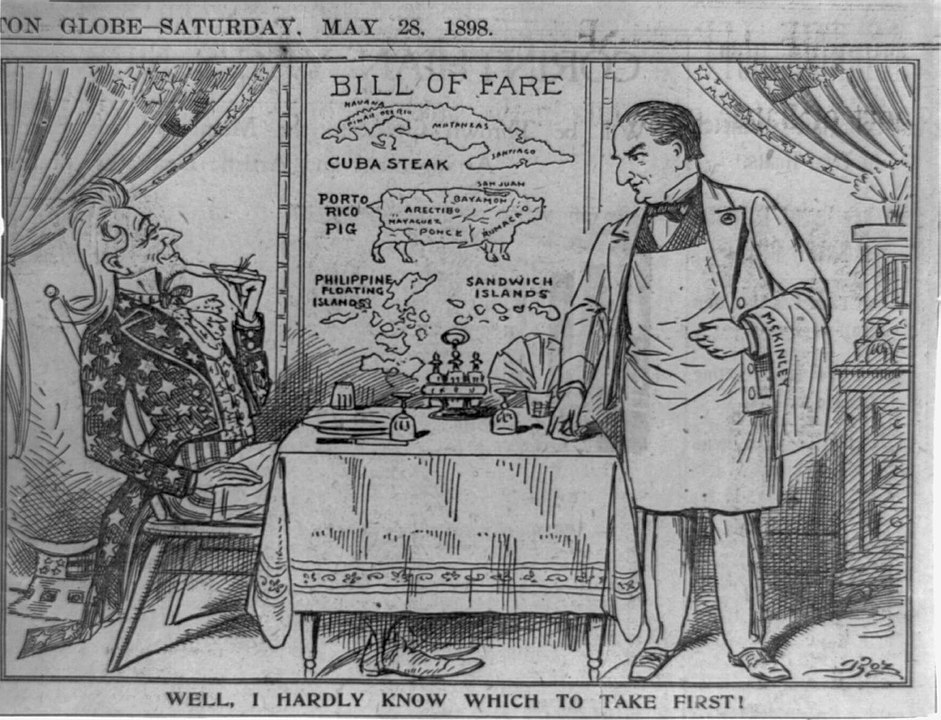

In the last years of the 19th century and first years of the 20th, the nation embarked on an imperialistic struggle against the crumbling Spanish empire. There was ferocious resistance to what became the Spanish-American War, and even more opposition to annexing the Philippines after the war was won.

But Theodore Roosevelt, though not yet President, and others helped create an awareness of American options, and persuaded the public to move ahead in that direction. TR, who became known for his embrace of the “bully pulpit,” was a master with his buoyant personality in persuading the nation to move ahead, just as he had cajoled the Rough Riders on San Juan Hill.

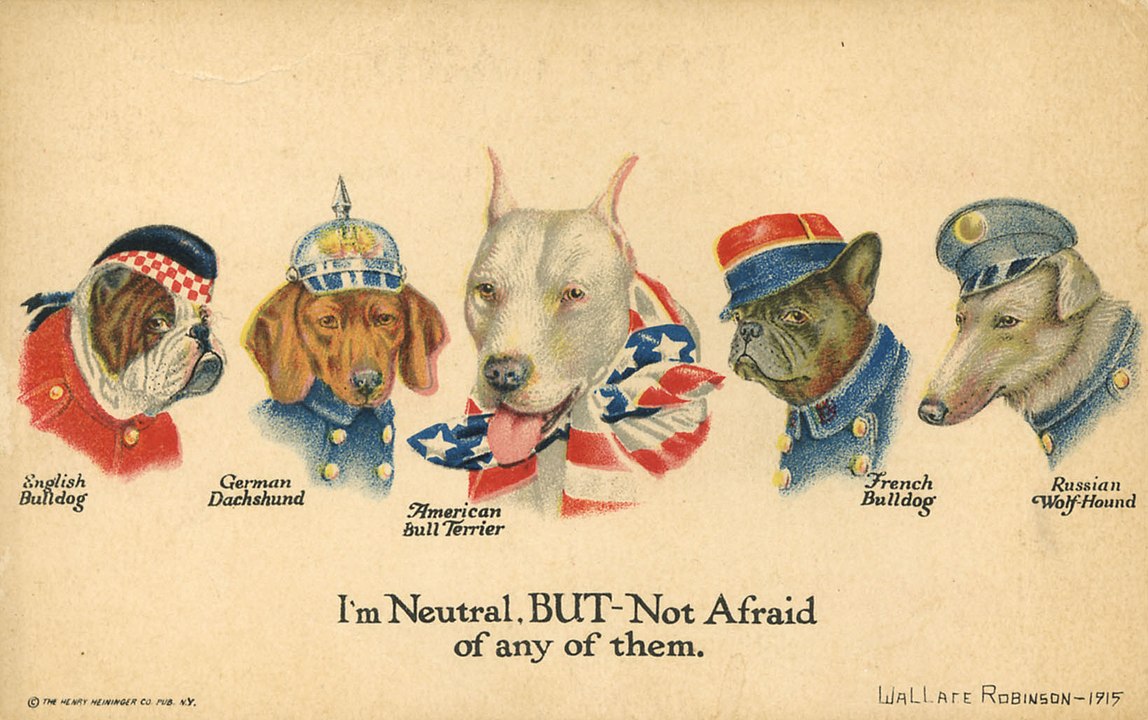

There was an even greater need for common purpose as the Great War, what we Americans came to call the First World War, beckoned in the 2nd decade of the 20th century.

German submarines were sinking American ships, or British ships (like the Lusitania) with Americans on board. But Americans did not want to become involved in the war. Indeed, the slogan shouted at the Democratic National Convention that nominated Woodrow Wilson for a second term in 1916 was “He kept us out of war.”

With his eloquent speaking ability, Wilson was able to persuade the nation that this could be a war to end all wars, and that the United States could make a crucial difference. And Americans embarked on this Wilsonian crusade with a sense of exuberance, no better reflected that in George M. Cohan’s famous song “Over There.”

Americans went willingly into battle. And people on the home front were ready to make sacrifices, such as not eating meat one day a week, so that food could be used to feed starving civilians in Europe.

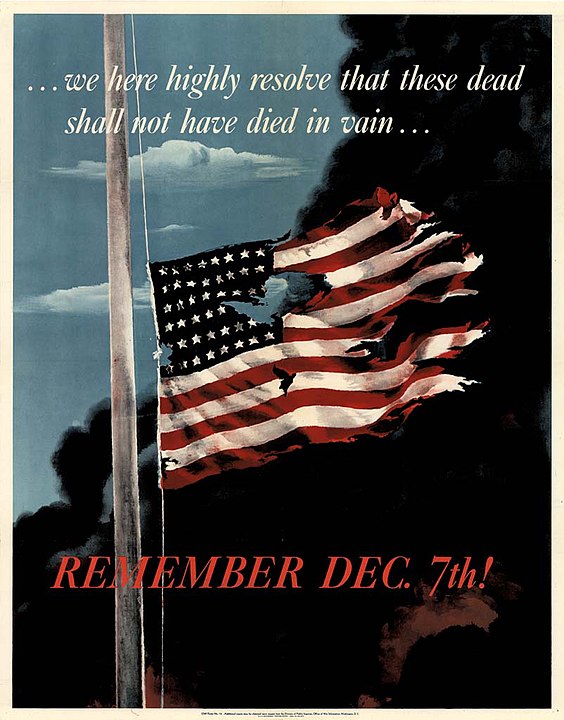

There was a powerful consensus created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt that lasted for the duration of the Second World War. FDR faced a powerful isolationist wing, both in Congress and in the country at large, in the late 1930s, but he moved slowly, taking one step at a time, and by the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he had the support for what was really extensive American involvement in the war.

Roosevelt could coin a phrase, as he did when he called on the nation to be the “arsenal of democracy,” and he also knew how to hire able people, who had the confidence of the country, to take the steps necessary to produce everything that was necessary for war, and to help Americans feel that they were involved in the struggle.

“Don’t you know there’s a war on?” was a common refrain, and Americans wanted to do their part.

Roosevelt was a masterful politician who knew how far to push. A Democrat, he was well aware he had to work with Republicans, and he persuaded them to support him on everything he did to support the war, even as he acquiesced to their demands on the home front.

So he allowed the WPA and other New Deal agencies that Republicans hated to fade away, all the easier because the demands of wartime production brought about an end to the Great Depression.

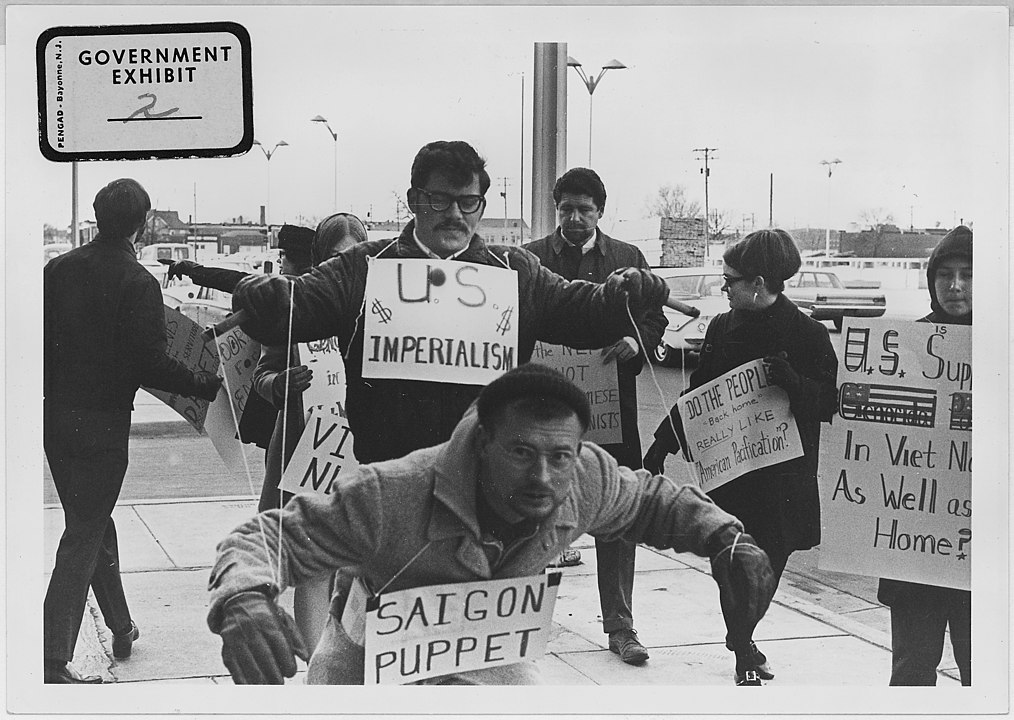

In the 1960s, President Lyndon B. Johnson discovered that it was impossible to do what he wanted to do in the Vietnam War without the support of Americans at home. And his aggressive, sometimes abusive, actions helped create the unrest and fragmentation that ultimately brought him down and led to American defeat in the war.

Vietnam War protesters in Wichita, Kansas, 1967.

Consensus and common purpose are therefore absolutely crucial in a time of crisis. So why then are we at such an impasse in our collective response to the COVID-19 crisis now?

Gone are the days when politicians were willing to compromise with one another in the interests of the common good.

When he was Senate Majority Leader, Lyndon Johnson could fight furiously with Everett Dirkson, his Republican counterpart, on the floor of the Senate, then adjourn together to his office to drink bourbon and branch water.

Since the time that Newt Gingrich led the House of Representatives, political opponents have come to be seen as enemies, in a process that has only grown more intense in recent years.

But presidential leadership, so important in crises past also makes a huge difference.

It is one thing to declare oneself a “Wartime President,” another entirely to create a sense of common purpose that people can accept. Everyone who has been successful in a crisis has worked to create that consensus, rather that castigating his enemies. And it helped account for American success in those wars.

Lyndon Johnson, a larger than life personality, not unlike Donald Trump, assumed he could do anything. He found, much to his dismay, that he was dismally wrong.

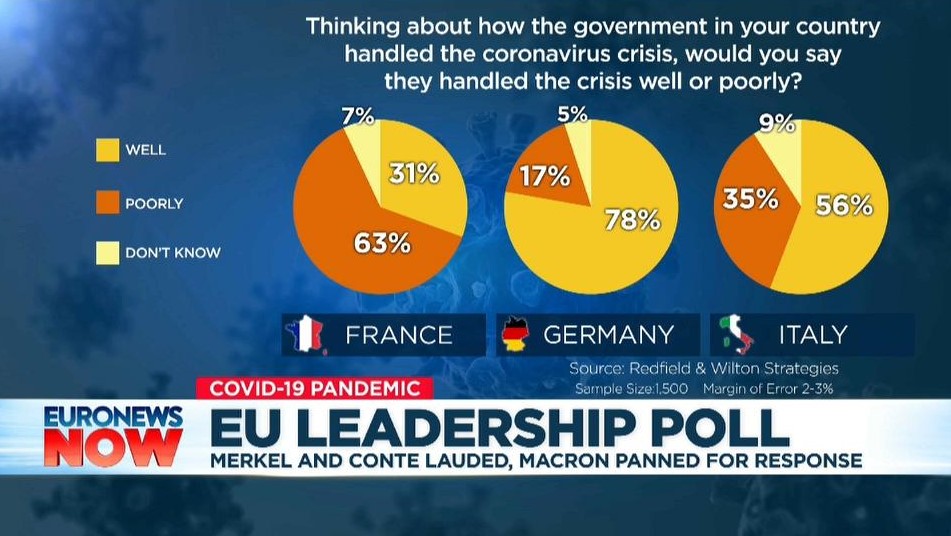

Consensus and a sense of common purpose are making a difference today. German Chancellor Angela Merkel brought Germans together for “collective action” in response to COVID-19 and the death rate there is dramatically lower than in the United States.

Meanwhile, there is little consensus about whether or how to open American schools and businesses, and Americans continue to fight over whether to wear protective masks. Real leadership could make a huge difference.