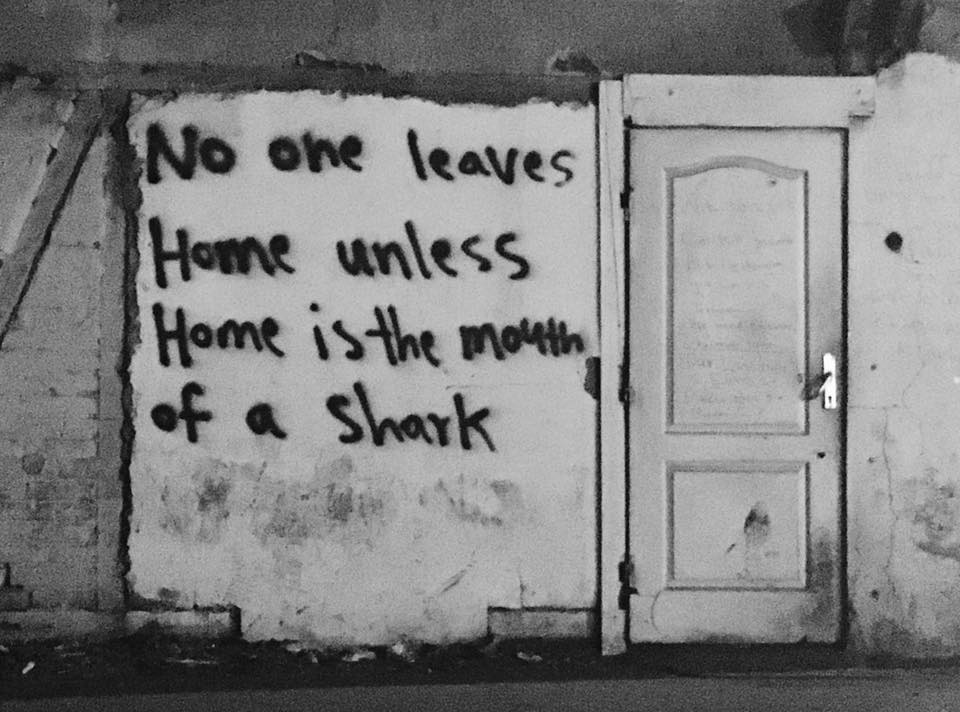

Graffiti outside of the Belgrade barracks.

I met Jamil in Subotica, Serbia, 15 miles from the Hungarian border. He had a sunken face and dark circles under his eyes. “If you saw my picture on Facebook, you would not recognize me,” he wearily told me. For three months he had been stuck in Serbia, and after nine failed attempts to enter Hungary, he was growing increasingly hopeless.

Jamil is from Swat, Pakistan, where he was pursuing a graduate degree in computer engineering. He left seven months ago because he was not religious enough for the Taliban, who had occupied his village. Fearing for his life, he left everything behind and departed for the European Union. All that stands in his way is the border fence spanning 109 miles along the Hungarian – Serbian border, restricting entry for Jamil and thousands of other refugees who remain trapped in Serbia.

Hungary completed its first razor-wire border fence in September 2015 as a response to the hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees who irregularly entered the country that summer. The fortified border is not the only obstacle restricting irregular entry into the country. Hungary has also recruited over a thousand new border hunters deployed solely to remove anyone who enters Hungary illegally.

As he waited for another opportunity to test his luck, Jamil was living in Ciglana, an abandoned brick factory, with 60 other Afghan and Pakistani men. The empty building has housed refugees and migrants en route to Western Europe for years, but what used to be a short-term campsite has become a semi-permanent residence for many who have repeatedly failed to cross the border.

For Jamil and the other refugees in Serbia, trying to cross the border is a game; hiding out at night along the fence, waiting for the guards to pass, using cheap tools to cut through the barbed wire and stealthily attempting to travel five miles into Hungary, where they will be safe from police who otherwise have the jurisdiction to facilitate push-backs into Serbia.

Jamil claimed that the Hungarian border guards caught and beat them. Once they even forced him and his friends to strip naked and stand in knee-deep snow for hours, resulting in hypothermia and the death of one of them. Reports of Hungarian police beating irregular entrants are widespread.

Refugees eating lunch outside the barracks.

There are currently 8,000-10,000 refugees stuck in limbo in Serbia; the majority are Afghan and Pakistani young, single men. Hungary only processes 10 asylum applications each day, prioritizing families, single women, children and elderly people. For these men the wait-time to have their asylum application processed could take up to three years.

The Hungarian government recently approved the construction of a second fence, which will be finished by May 2017. The new ‘smart fence’ is designed to be impenetrable; it is equipped with thermal cameras and alarms that will notify guards when people are approaching. One fence severely restricted entry; two fences will make it nearly impossible.

The Barracks

Although Subotica is the closest Serbian city to the Horgos border crossing, most refugees can be found 125 miles south in Belgrade. In February 2017, there were over 600 new arrivals in Belgrade. Eighty percent of refugees are officially registered and staying in open reception centers, but these centers are outside of the city and many prefer to live closer to the city. It is estimated that up to 1,100 Afghan men choose to live rough in abandoned barracks next to the central bus station.

Refugees in a barracks camp in Belgrade, Serbia stand in a lunch line.

Life in the barracks is dirty and deplorable; there is no electricity, clean water or toilets. There are piles of garbage everywhere and rats run rampant. The men living there have created makeshift campsites that vary in composition. Some include wood-burning stoves, tents and rugs, but many just contain a mattress and blankets.

The corridor between two rooms in the barracks.

Inside the barracks.

Inside the barracks, men burn small fires to keep warm and boil water for tea. The air is thick with toxic smoke, which is caused from burning railway wood that is coated in chemicals. At any time of the day, the ground is full of sleeping people, hidden under layers of blankets.

Three friends in the barracks. The man on the right had just returned to Belgrade from an unsuccessful attempt to cross into Hungary.

On a Sunday afternoon as I walked through the barracks, I met Jawed. He is a 16 year old from a rural Afghan village who is traveling with his cousin and four friends. Despite their lack of provisions, Jawed invited me for tea. As we waited for the water to boil, we played cards and they told me about Afghanistan. Jawed claimed it was such a bad country because it is so dangerous. Both Da’esh (ISIS) and the Taliban occupy the area where he is from. As uneducated, poor boys, Jawed and his friends were perfect targets for Taliban recruitment.

From their perspective, staying in Afghanistan meant living a life of fear and an early death; therefore it was worth the risk to head west and to reach a better life in Europe. Jawed’s story of Taliban persecution is common among all the unaccompanied minors I met. They also seemed to have a skewed perception of easy life would be for them in Europe.

Unaccompanied minors from Afghanistan in the Belgrade barracks.

Smugglers

Life in the barracks is difficult and uncomfortable, but it allows the men to be close to “Afghan Park,” where the smugglers are found.

With the closure of borders along the so-called Balkan route and the limited opportunity to apply for asylum, refugees place their trust in smugglers.

Several refugees reported they are paying up to $10,000 to travel from Pakistan and Afghanistan to Western Europe. They pay in increments; after each successful border crossing they compensate the smuggler or network of smugglers who helped.

The methods of payment vary; some pay the smuggler directly, while others rely on family members back home to pay an agency after a successful border crossing. By the time they reached Serbia, they have paid 80-90% of the total cost of the journey.

In Afghan Park, the smugglers are conspicuous. Wearing expensive clothes and surrounded by groups of refugees, they are easy to distinguish. Full of promises of successful border crossings, they inflate the hopes of refugees.

Horgos border crossing with the Hungarian border fence in the distance.

Their means of transporting the refugees have varied over time depending on the situation at the Hungarian border. When the fence was first built, smugglers knew which border guards would accept bribes. However, with hundreds of new border hunters who have undergone vigorous training, bribing a border guard is no longer a viable option.

Now the most common form of assistance offered by the smugglers is to cut the fence and send the refugees through. Once safe inside Hungary, another smuggler is appointed to drive them to the Austrian border. With the construction of the second border fence in Hungary, the route is changing again. Now smugglers are transporting refugees to Sid, Serbia and promising them access to Croatia by riding a cargo train. Although this option is dangerous, some take the risk, believing it is their only chance to move west.

Aid Agencies

At the height of the crisis, in the summer of 2015, Serbia was simply a transit country, where over 600,000 refugees and migrants quickly passed through before reaching the Hungarian border and continuing on to Western Europe. But today, with the Balkan route effectively closed, aid organizations have had to quickly build capacity to serve the new population of refugees.

Refugee Aid Miksaliste is one grassroots organization that provides services for refugees. Save the Children, UNHCR, Praxis, Oxfam and the International Rescue Committee all operate out of their building to provide legal services, psycho-social support and to distribute supplies. Hundreds of men come to use these services and warm up, use the Wi-Fi and charge their phones.

Refugees in Miksaliste warming up, charging their phones, and using Wi-Fi.

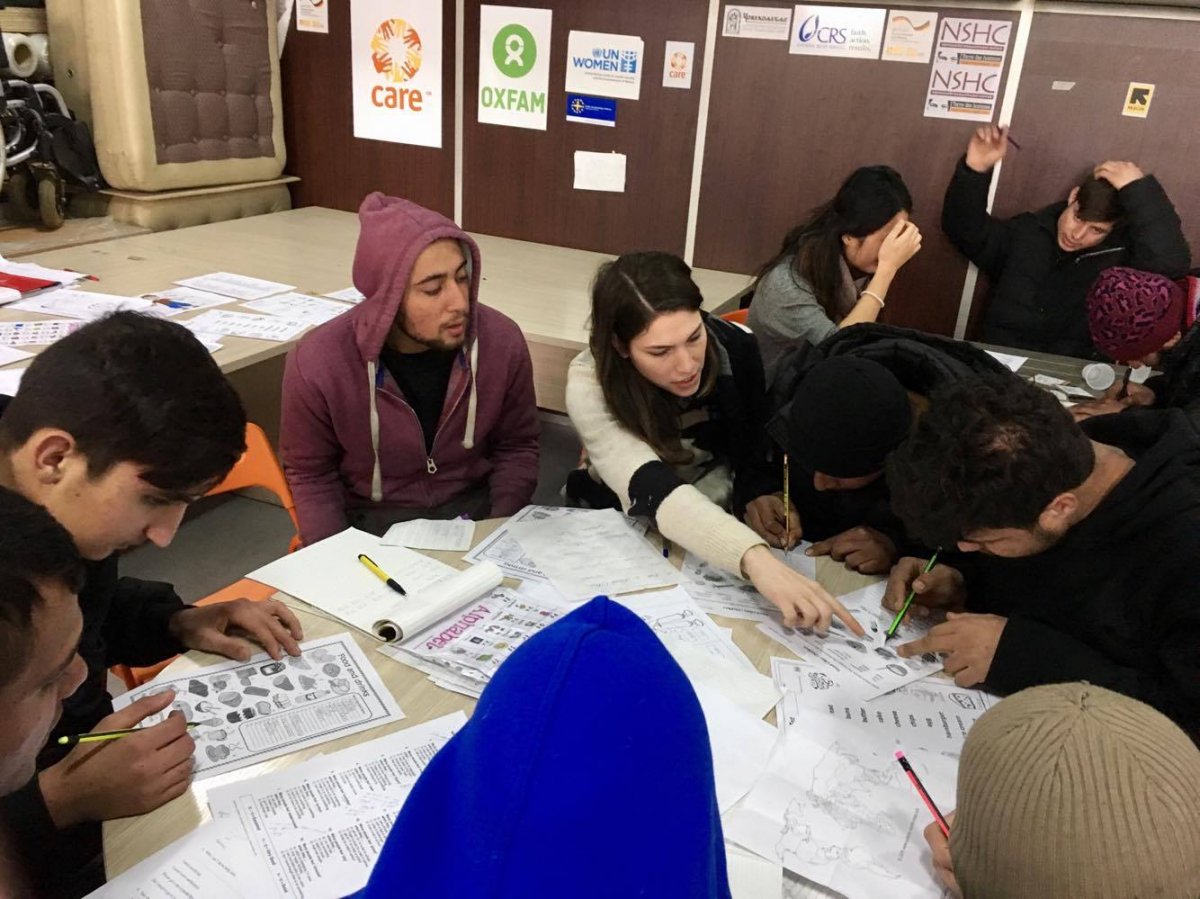

They also offer improvised English lessons and activities for the refugees in order to stimulate their minds. English lessons happen three times a day, six days a week, with volunteers coming on an ad hoc basis, teaching anything from the ABCs to distributing Chekhov texts with comprehension questions.

A photo of the author teaching an English lesson in Miksaliste.

Info Park is another local NGO that provides similar services. A representative from the organization explained that there is a critical need for psycho-social services for many of the refugees, as they have experienced trauma in their countries of origin and along the migration route. They experience further hardship and increased hopelessness after repeated failed attempts to cross the border. These individuals return to Belgrade desperate and depressed and in need of counseling.

Local NGOs and their cooperating partners provide essential services to maintain a decent standard of living for the refugee population. However, they are small organizations and have been stretched thin to cope with all the people in need. With the warm weather approaching and the construction of Hungary’s new fence, more refugees are likely accumulate in Serbia. Only time will tell what their future will hold, but for those waiting in limbo time moves slowly and hope dies fast.

[All photos by author]