In July 1995, in the final days of the Bosnian War, over 8,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) men and boys were killed in the Srebrenica massacre. As the largest case of mass violence in Europe since World War II, Srebrenica serves as a poignant reminder of the dynamics and consequences of extreme nationalism, the long legacies that acts of violence leave on individuals and communities, and the importance of remembering and preserving their testimonies.

The Bosnian War was one in a series of conflicts that marked the breakup of the multiethnic nation of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Formed after the end World War II as a federation of six republics, Yugoslavia was composed of a diverse mix of religious and ethnic groups. However, after the death of longtime President Tito in 1980, political and economic instability intensified and tensions between the republics increased.

Amid growing frustrations with the consolidation of power around the Serbian republic and divisive rhetoric of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, Slovenia and Croatia seceded in 1991. The following year Bosnia-Herzegovina—the most diverse of the Yugoslav republics, composed of 43% Bosniaks, 31% Serbs, and 17% Croats—followed suit.

Ethnic map of the former Yugoslavia based on 1991 census data.

Bosnia’s secession triggered a sharp intensification of nationalist rhetoric among the republic’s political leadership. The Bosnian Serb leadership, headed by Radovan Karadžić and supported by Milošević, called for the Serbian population in Bosnia to separate and unite with those in the neighboring Republic of Serbia.

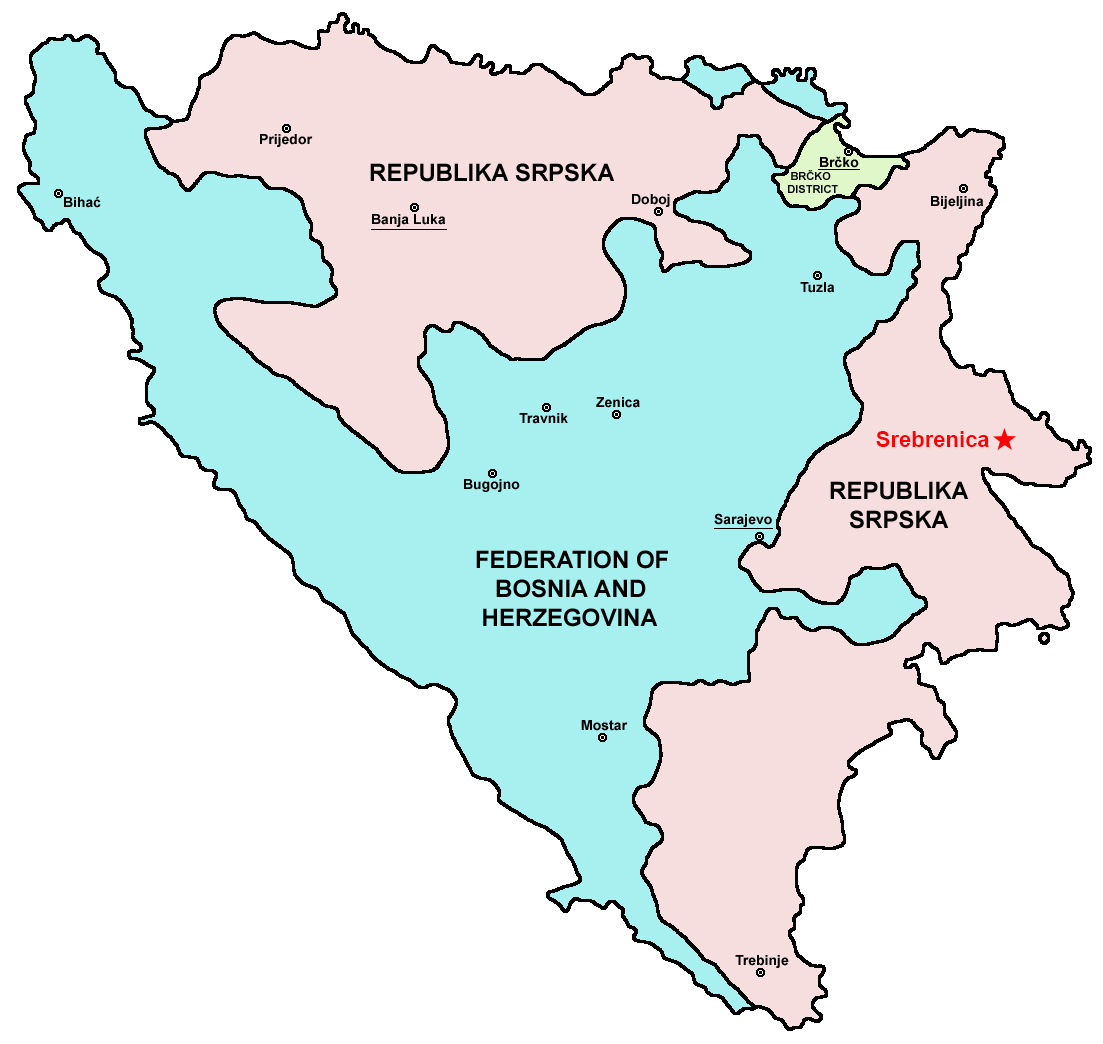

Shortly after the European Community formally recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina’s independence on April 7, the Bosnian Serb leadership declared its own autonomy from the newly-formed Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and initiated a military campaign to carve out territory in eastern Bosnia for what came to be called Republika Srpska.

From the war’s beginning, reports circulated that small groups of Bosnian Serb paramilitary forces were committing acts of “ethnic cleansing” of non-Serb populations in territories adjacent to the republic of Serbia and rump Yugoslavia. As the conflict spread, divisive nationalist rhetoric and acts of mass violence escalated across the region, intensifying fears and fracturing communities that had lived peacefully alongside one another for decades.

Located just ten miles from the eastern border and inhabited by a diverse population that included roughly 64% Bosniaks and 28.5% Serbs, the town of Srebrenica fell to Serbian nationalist paramilitaries in 1992. It was then recaptured and held by Federation forces, and became a haven for non-Serbs fleeing conflict in the surrounding area.

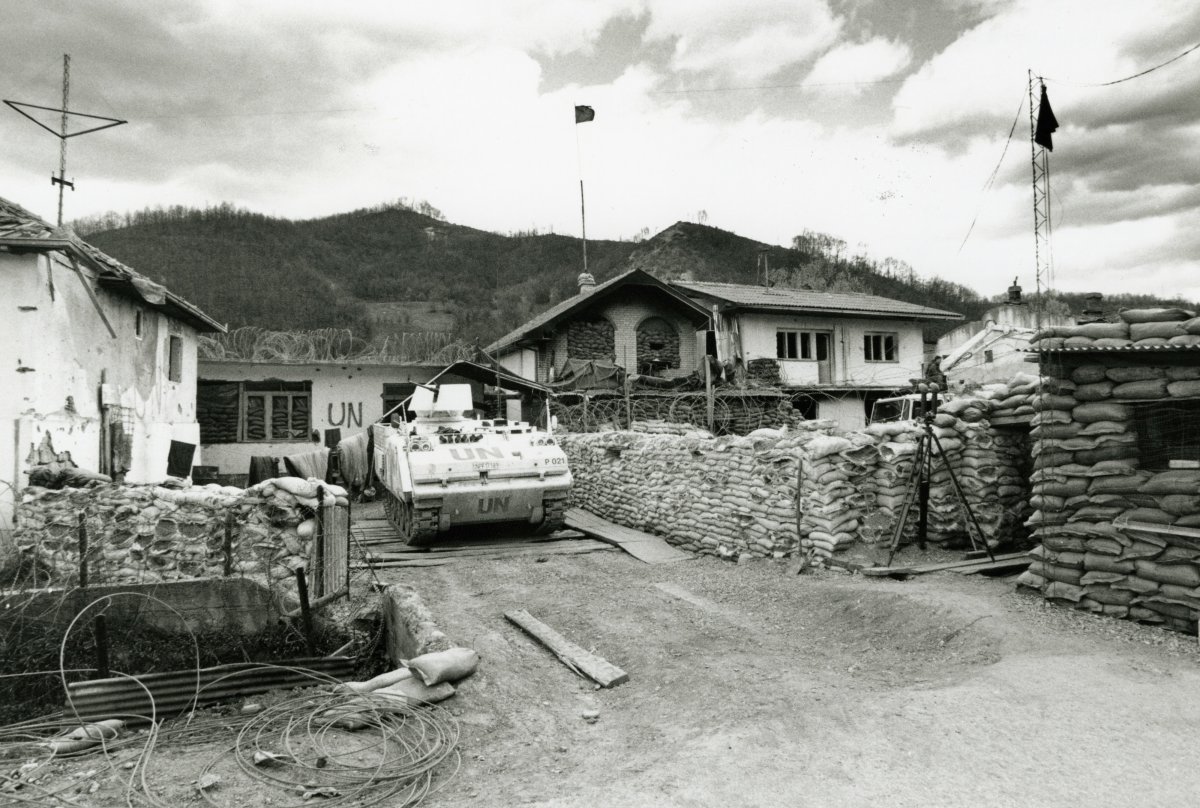

In April 1993, the UN Security Council declared Srebrenica the world’s first “safe area” under the protection of UN Peacekeeping Forces. However, the small battalion of lightly-armed Dutch peacekeepers were ill equipped to enforce agreements or defend the town, which swelled to as many as 60,000 people. By 1995, only 370 peacekeepers were stationed in Srebrenica, and conditions had deteriorated as few supply convoys carrying food, medicine and fuel were able to reach the enclave.

On July 6, 1995, under orders from Karadžić, the Bosnian Serb army began advancing towards Srebrenica. As Dutch UNPROFOR (United Nations Protection Force) units began taking fire, they abandoned their observation posts or surrendered as NATO forces failed to provide meaningful backup.

This Dutch UNPROFOR observation post in Srebrenica took heavy fire from Bosnian Serb troops in 1995.

On July 11, Bosnian Serb forces under the command of General Ratko Mladić entered the Srebrenica safe zone. As the town fell, roughly 20,000 people sought refuge just north of Srebrenica at the UN peacekeeping compound in Potočari.

That night, around 15,000 Bosniak men also left Srebrenica in an effort to reach safety, most heading about 60 miles north to Federation territory near Tuzla. Bosnian Serb forces pursued the men. Artillery and ambushes fractured the column and officers used promises of safety to induce thousands to surrender.

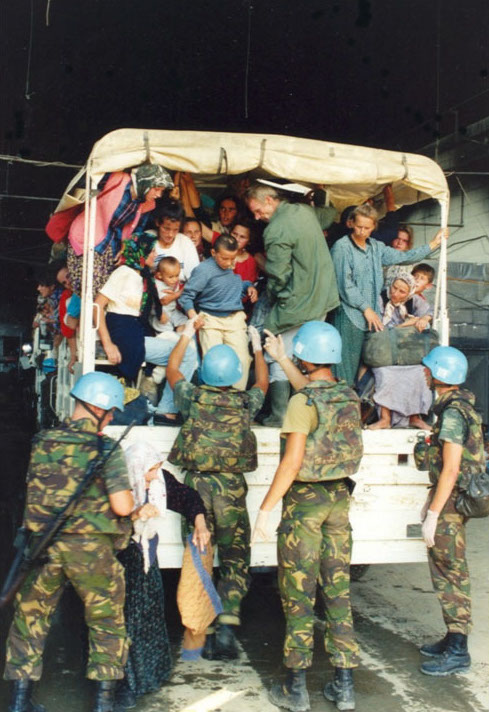

The following day, Bosnian Serb forces entered the UN compound in Potočari. With UN peacekeepers looking on, Bosnian Serb officers began the forced transfer of women, children, and the elderly by bus to Federation territory, while “military age” men and boys were separated under the premise that they would be interrogated.

Reports of atrocities including summary executions, rape, and torture circulated almost immediately. While women, children, and the elderly were deported, over the course of the following week the men from Potočari, as well as those captured from fleeing columns were transported to detention sites in schools and warehouses in towns and villages nearby and forced to turn over their belongings.

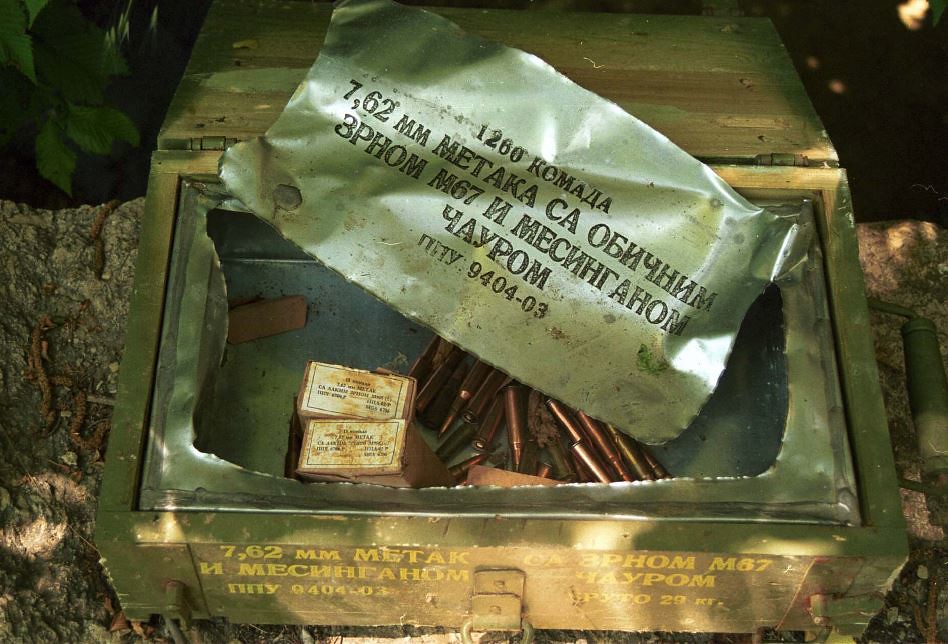

Some were killed individually, but most were then systematically transported to execution sites, shot, and buried in mass graves. In the months that followed the killings, Bosnian Serb forces attempted to hide their crimes by reburying the bodies in secondary graves scattered across the region.

In the wake of the Srebrenica killings, attacks on other “safe areas,” and continued violence, NATO intensified its first-ever use of force operations. Operation Deliberate Force conducted sustained air strikes against targets in Serb-held Bosnia from late August into September.

Though earlier rounds of negotiations had largely failed, a peace deal was finally reached in November in Dayton, Ohio, which recognized the integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but divided it into two territories along ethnic lines: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska. By its end, the war had resulted in over 100,000 casualties, and over two million displaced persons.

In the years that followed, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (established in 1993) prosecuted a range of war crimes committed by individual Serb, Croat, and Bosniak combatant parties.

In 2001 the court ruled that the atrocities at Srebrenica met the legal definition of genocide. To date, international and Bosnian state courts have sentenced 40 individuals for acts related to Srebrenica, including Karadžić and Mladić, who were both found, among other crimes, guilty of genocide in Srebrenica and sentenced to life imprisonment.

The war’s legacies continue.

Some displaced by the conflict still live in refugee areas established during the war, and the identification and return of victims’ remains through DNA analysis has been a long and painful process—not only in Srebrenica, but at other mass graves around Bosnia.

Each year on July 11, commemorations at the Srebrenica Memorial (established in 2001) have centered on the burial of newly identified loved ones, attended by family and friends who still live in Bosnia, as well as those displaced internationally by the war.

Preserving the testimonies and memories of those affected by these events and providing global access to their stories have also been at the forefront of commemorations. Among other activities, Remembering Srebrenica has created an online exhibit, while the Srebrenica Memorial Center has released video tours of the site in Potočari and worked collaboratively with the War Childhood Museum to document the experiences of those who were children during Srebrenica.

Bosniak women participate in a reinterment and memorial ceremony at the Srebrenica Memorial in 2007 (left); identified Bosniak victims are buried in 2007 (right).

However, even as efforts to preserve, remember, and educate persist, observers have also worried that paralleling currents of revisionism and denial have expanded, too. Today Bosnia remains a politically and structurally divided country, and while many Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks in the region have sharply criticized nationalist politics, Srebrenica itself has become increasingly politicized.

Despite meticulous documentation of evidence, convictions, and numerous international and national resolutions, this year, the memorial center issued a 56-page report that highlighted increasingly mainstream tendencies in Republika Srpska and Serbia to dispute the number of deaths, glorify war criminals, and undermine the legitimacy of convictions by claiming they were conducted under an anti-Serb bias.

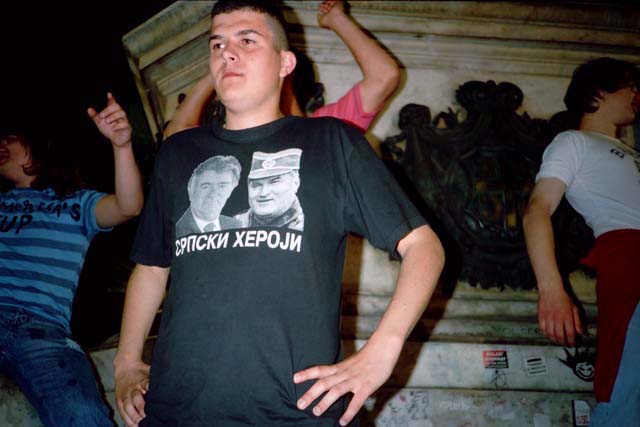

A Serbian youth wears a t-shirt that calls Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić "Serbian heroes."

In 2018, Bosnian Serb politicians in Republika Srpska retracted a 2004 report acknowledging the genocide, and instead established a new panel to review the events and the number of victims.

Beyond the region itself, observers also warn of the normalization of denial in international intellectual circles. In 2019, hundreds of protesters and observers criticized the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Peter Handke for his support of Slobodan Milošević and minimization of war crimes.

The Bosnian War has also increasingly become a touchstone among global nationalist and Islamophobic currents, and at its most extreme, served as a point of reference for Norwegian mass shooter Anders Breivik, who killed 77 people in 2011, and the New Zealand Christchurch mosque shooter in 2019.

Although observers have often resorted to fatalistic accounts of “ancient ethnic hatreds” to explain the Bosnian War’s outbreak, few anticipated the scale of the violence that ensued, even as Yugoslavia began to break apart.

To many ears, the places, names, and events of the war may sound complex and remote. But we would do well to remember that Srebrenica’s legacies continue and its lessons remain as salient as ever. In today’s context of resurgent nationalisms and polarization, the Bosnian War warns us to be mindful of the dangers of extreme nationalism and the rapid descent into violence to which it can lead.