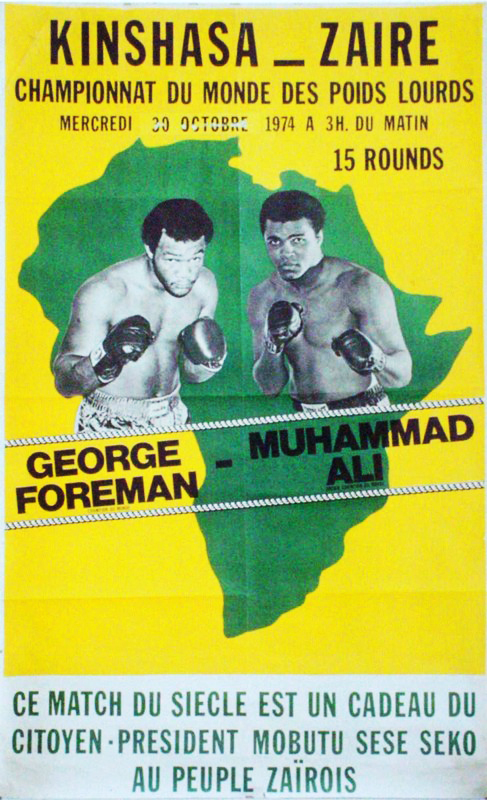

October 30, 2019, is the 45th anniversary of the so-called “Rumble in the Jungle,” George Foreman’s 1974 heavyweight title defense against Muhammad Ali in Kinshasa, Zaire.

The fight was a major turning point in the careers of both men, particularly Ali. It was the moment he regained the heavyweight championship he’d forfeited in 1967 as a result of refusing induction into the U.S. Army. It was also the moment, perhaps ironically, at which his public image began to turn decisively away from “divisive black nationalist” and toward “broadly popular American celebrity.”

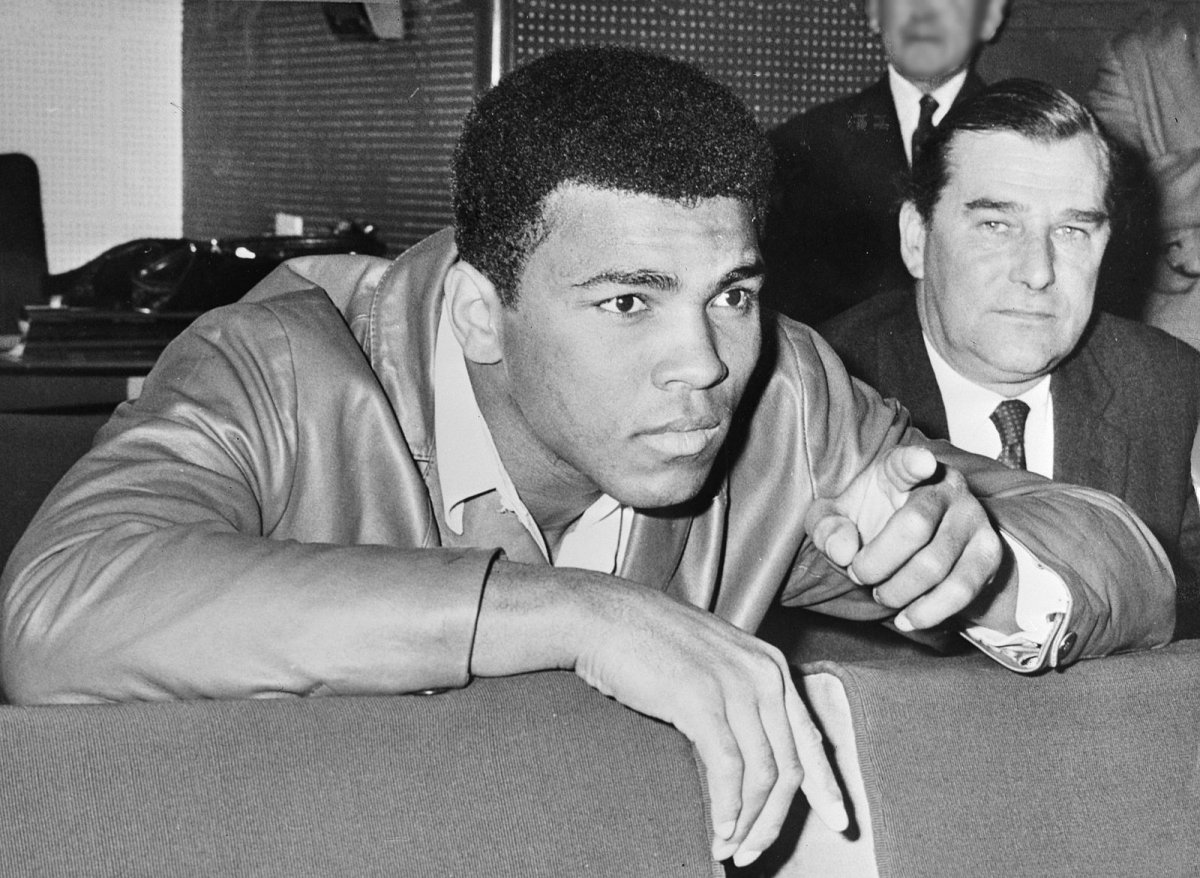

Born Cassius Clay, Ali won a gold medal at the Rome Olympics in 1960 and then rose quickly up the ranks of heavyweight title contenders. His initial public persona was bright, charming, and telegenic, and he immediately placed himself among the very small number of fighters in history who were as entertaining to listen to or read about as they were to watch in the ring.

Upon winning the heavyweight title in 1964, he announced himself a member of the Nation of Islam and instantly became the country’s most famous black nationalist; upon being classified 1-A for the draft, he stated his intention to refuse induction and sought to be re-classified a conscientious objector on the basis of his status in the NOI.

Ali had been able to resume fighting in 1970 while he appealed his conviction for draft evasion. His first effort to regain the heavyweight title, however, failed at the hands of Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden on March 8, 1971. Billed as the “Fight of the Century,” it was Ali’s first professional defeat.

Frazier continued to hold the title until 1973, when he lost it in a brutal two-round, six-knockdown bout to Foreman, famous for its “Down goes Frazier!!” call by Howard Cosell.

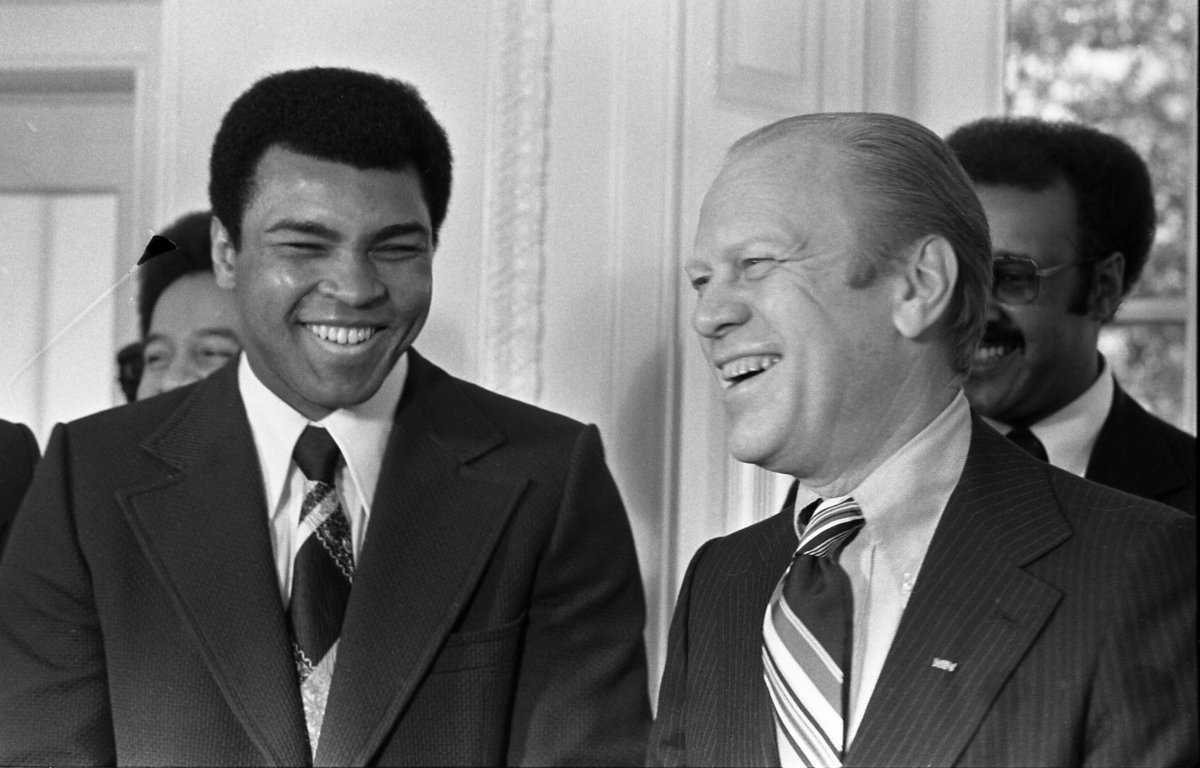

Muhammad Ali in 1966, the year he refused induction into the United States draft.

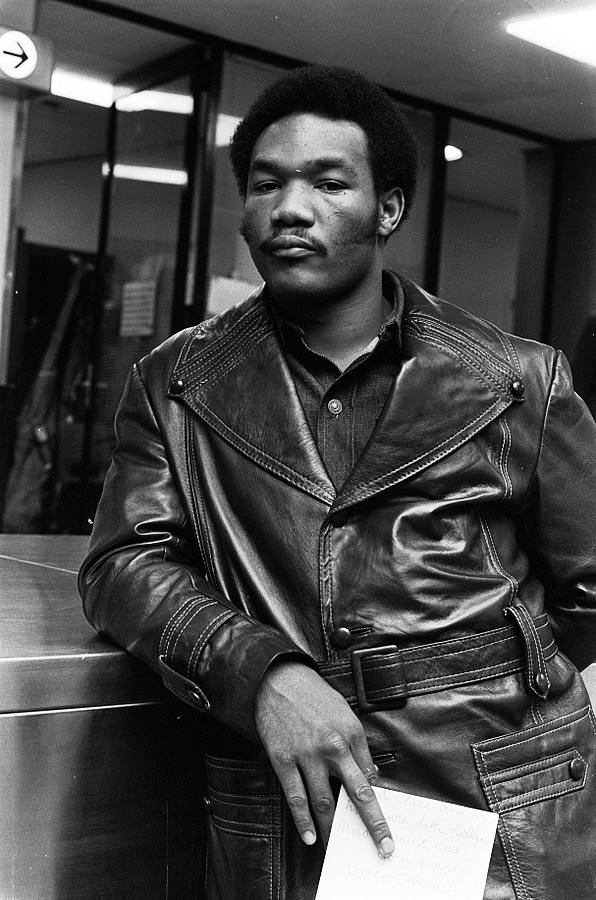

Foreman was a very different cultural figure from Ali.

His first national fame came from a very conventional act of Cold War patriotism. After winning the heavyweight gold medal at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City over Soviet boxer Jonas Cepulis, he celebrated in the ring with a tiny American flag. In the minds of many fans, this stood in sharp contrast to the Black Power protest staged by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at those same Olympics, and to Ali’s black nationalism.

Foreman was also a very different personality from Ali, quiet and taciturn rather than bombastic and loquacious, and his fighting style differed significantly as well. Ali at his best relied on quickness, footwork, and finesse, while Foreman won most of his fights the way he’d won against Frazier: with devastating power in the early rounds.

The fight was put together by an as-yet unknown promoter from Cleveland named Don King, a former numbers banker whose only previous fight promotion experience was a charity exhibition featuring Ali on behalf of a Cleveland hospital.

King was charming and charismatic enough to convince each fighter to sign a fight guarantee for $5 million apiece. King obtained these signatures without having yet obtained $10 million. He eventually got it from Mobutu Sese Seko on the condition that the fight be held in Zaire.

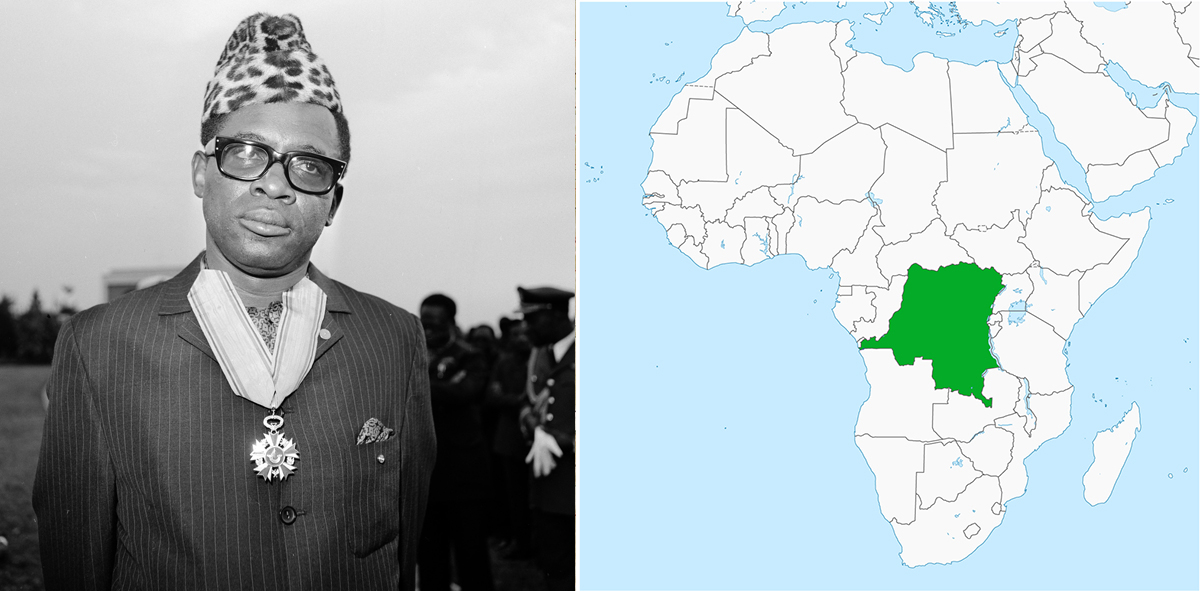

President Mobutu Sese-Seko of Zaire, 12 August 1973 (left); the location of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) within Africa (right).

But wait: Zaire?

Formerly the Belgian Congo (and presently the Democratic Republic of the Congo), it had been one of the most brutally exploited European colonial possessions in Africa. As with many former European colonies, its efforts after WWII to achieve independence and self-determination were drawn into the global polarity of the Cold War. The result was authoritarianism rather than pluralistic democracy.

Its first democratically-elected, post-independence leader, Patrice Lumumba, was regarded as pro-Soviet by the U.S. and Belgium; he was deposed and executed, and, after a series of coups, power passed to Joseph-Desire Mobutu. Mobutu built an authoritarian dictatorship which lasted well into the 1990s. He also took steps to de-Westernize his own and his nation’s identity, adopting the name Mobutu Sese Seko, encouraging African clothing and cultural styles, and eliminating European place names.

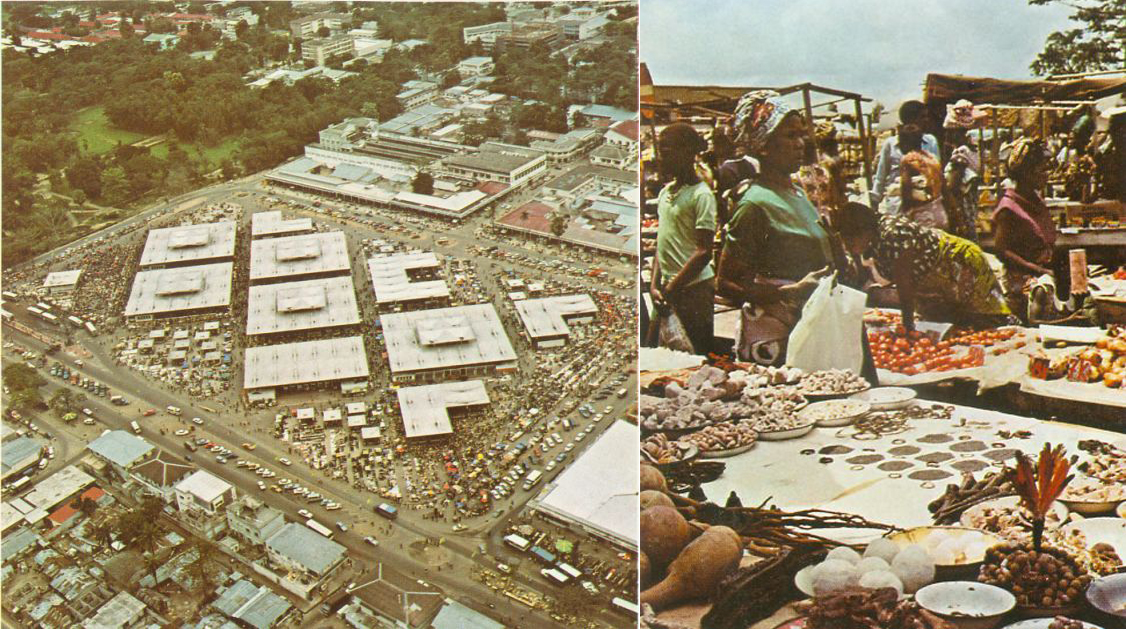

The central market of Kinshasa, Congo in 1974 (left); a woman shopping in Kinshasa's central market, 1974 (right).

The event was therefore packaged and promoted by King as a major back-to-Africa cultural event, including an associated three-day music festival featuring African-American artists James Brown, The Spinners, and B.B. King alongside African performers such as Miriam Makeba, TPOK Jazz, and Tabu Ley Rochereau.

An American film crew led by Leon Gast tagged along to film a documentary. Ali fell naturally into this style of patter and promotion. The phrase “Rumble in the Jungle,” in fact, was not a King promotional idea, but something Ali ad-libbed in front of the cameras while training for the fight.

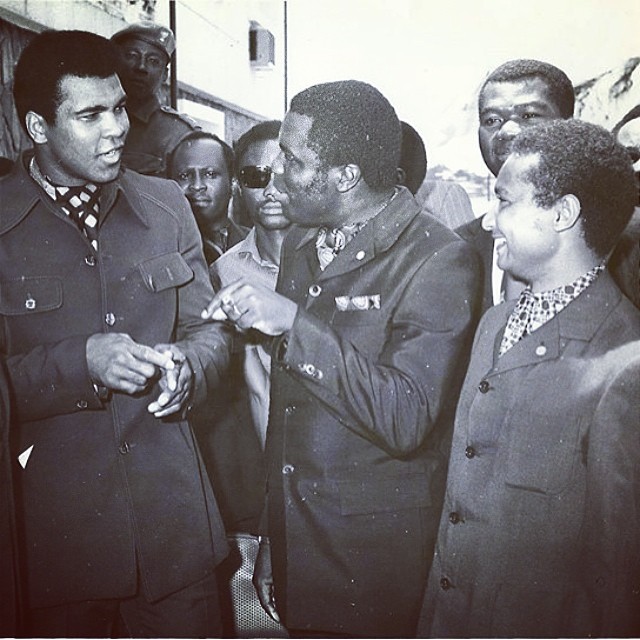

Ali, left, walking through the streets of Kinshasa in 1974.

As a live event in Zaire, the fight was a disaster.

Originally scheduled for September 25, the fight was pushed back over a month after Foreman was cut above the eye during a sparring session. This severed the fight from the music festival and forced the fighters, their entourages, and the media to remain in Zaire for the duration of the delay.

King anticipated thousands of well-heeled Western fight fans willing to pay top dollar to travel to Zaire to see the fight live; fewer than 50 turned up. On fight night, the crowd of 40,000 or so consisted overwhelmingly of locals who paid $10 apiece for obstructed-view seats far from the action.

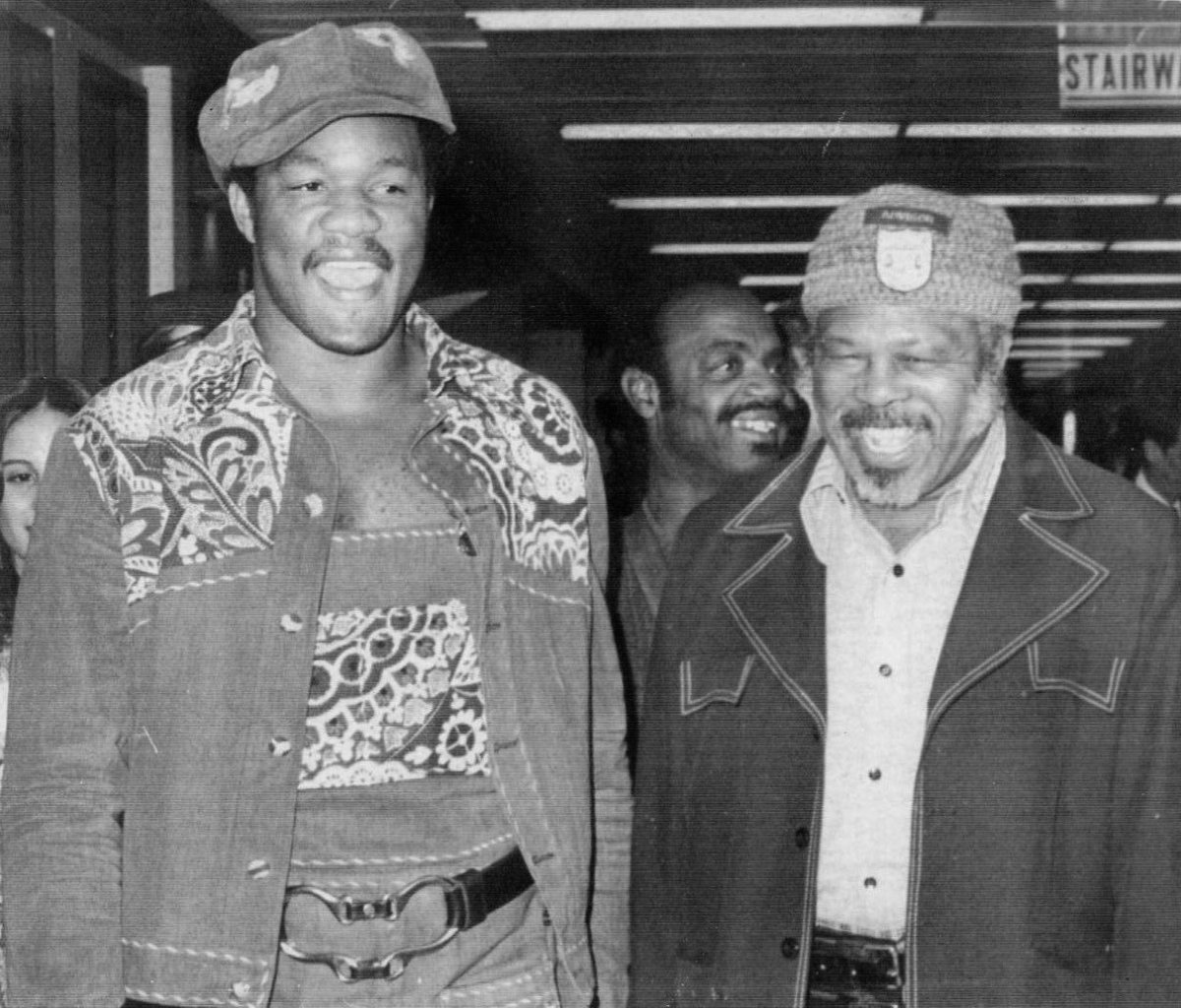

Foreman and his trainer, former champion Archie Moore, on their way to Kinshasa, 10 September 1974.

But by 1974, the “live event” part of a major championship fight was not the most important thing, either as a fan experience or as a payday for the promoters. It functioned as spectacle to promote the real business, which lay in the closed-circuit television and rebroadcast rights.

Live closed-circuit viewing of the fight was available in over 400 venues around the U.S., at prices ranging between $20 and $80, grossing an estimated $60 million. Including international markets, perhaps $100 million total came in from live closed-circuit and broadcast television.

The fight went off at 4 am local time so as to be shown on closed-circuit TV at 10 pm EST. When free TV and rebroadcasts around the world are factored in, perhaps half a billion people eventually saw the fight.

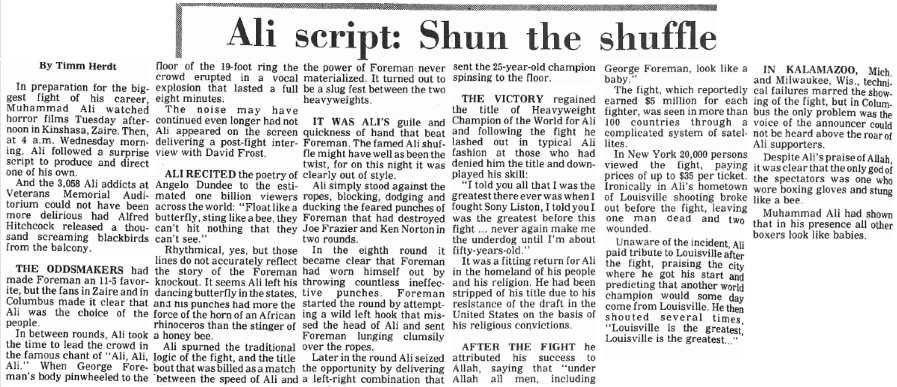

An article from The Lantern, the student newspaper of Ohio State University, reporting on spectators in Columbus watching the televised Ali-Foreman fight, 31 October 1974.

The fight itself was dramatic and entertaining. Foreman was favored. Everyone expected Ali to “dance,” to emphasize movement and footwork, mostly because he’d told everybody so all throughout training camp. Much of the boxing press, especially those rooting explicitly or implicitly for Ali, feared that he might be humiliated or seriously hurt if he took any other approach.

Instead, Ali came out aggressively in the first round, taking the fight to Foreman with a series of dramatic right-hand leads. For the next several rounds, Ali executed the so-called “rope-a-dope” maneuver — going to the ropes early in the round, inviting Foreman to tire himself by throwing body punches, attacking late in the round. Ali absorbed enormous punishment in the process.

His strategy was nevertheless eventually effective, and in the eighth round Ali knocked out an exhausted Foreman with a series of powerful combination punches.

George Foreman vs Muhammad Ali, October 30, 1974

Ali was only the second man ever to regain the heavyweight title, and the first, Floyd Patterson, had done so in an immediate rematch. This achievement was central to Ali’s subsequent place in the public imagination. Having lost the title as a result of his personal politics rather than in the ring, he regained it in dramatic fashion in front of the entire world.

In 1975, he defeated Joe Frazier a second time in the King-promoted “Thrilla in Manilla,” solidifying his claim as the greatest heavyweight of his era.

Ali’s reputation as a radical also began to soften, which further rehabilitated his image in the public imagination. American troops left Vietnam in 1973, and opposition to the war gradually diminished as a marker of controversy.

In February of 1975, Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, passed away. In the wake of his death, his movement split into two branches. One, led by his son Wallace Muhammad, transitioned away from black nationalism and toward more conventional Sunni Islam; the other, led by Louis Farrakhan, retained the old radicalism. Ali sided with Muhammad.

Gast’s documentary of the fight, When We Were Kings, wasn’t completed until 1996, by which time both Ali and Foreman were uncontroversial and beloved celebrities. Foreman, too, eventually regained a share of the heavyweight title — in 1994, at age 45.

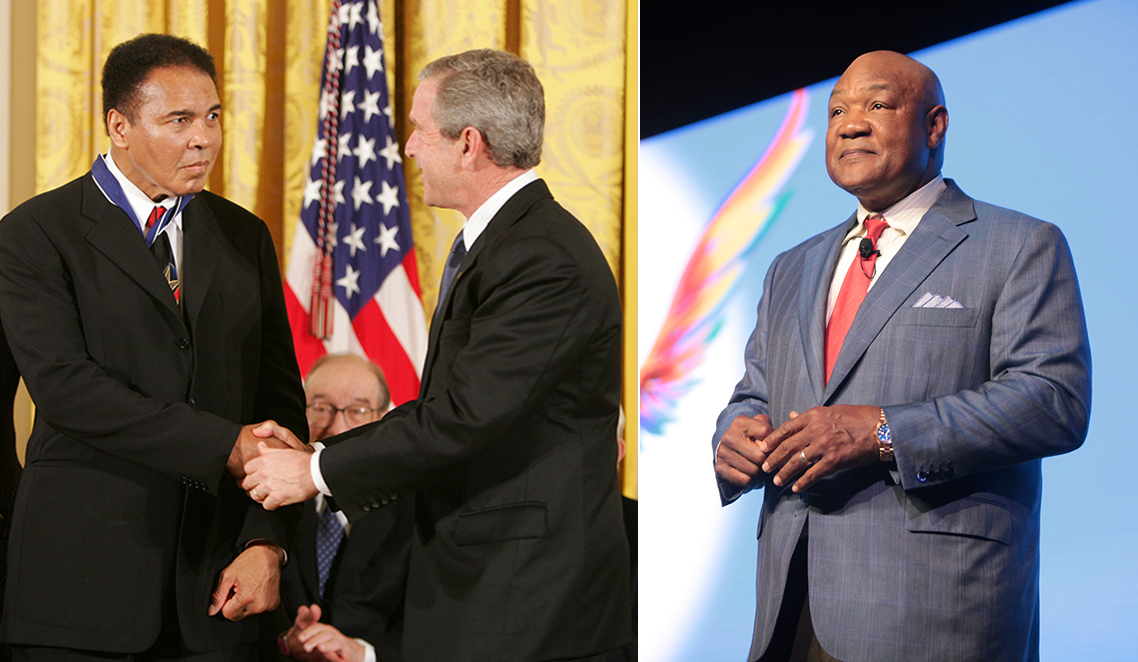

Ali and Foreman in later life: Muhammad Ali receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush, 9 November 2005 (left); George Foreman speaking at the 2016 FreedomFest, 15 July 2016 (right).

In 1996, Ali lit the Olympic Cauldron in Atlanta, Georgia. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, Ali appeared alongside Will Smith on America: A Tribute to Heroes as an explicit example of the compatibility of Islam with American culture.