What exactly is the “deep state”? Those words, used in such different ways, have given them power and allure. This month, historian Paul Croce gives us a history of the phrase, examining how fears of hidden powers, both real and imagined, have stirred liberals and conservatives, for national security claims and for seeking political advantage, with a recent surge in concern for the power of money impacting both parties.

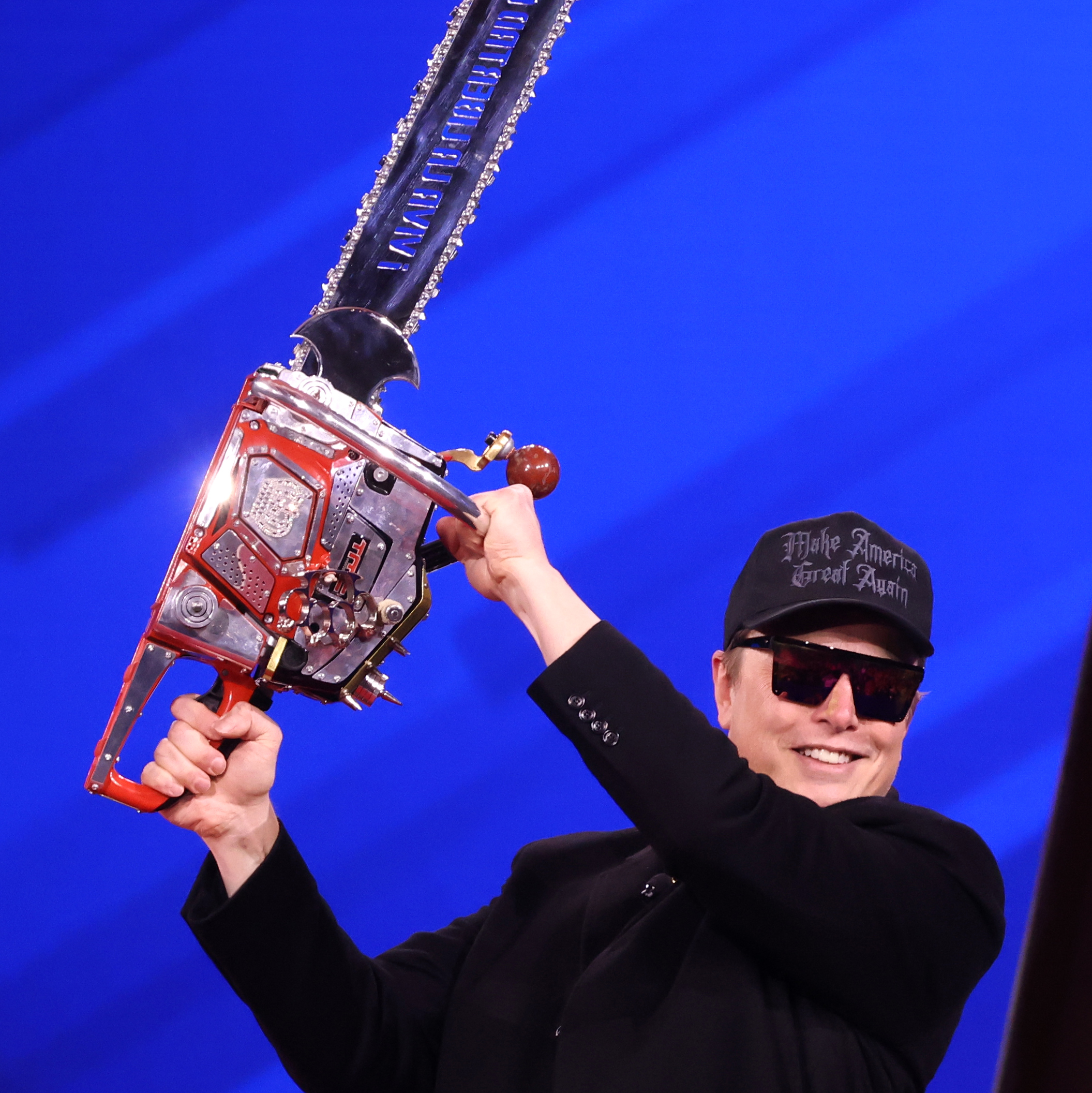

During his first hundred days in office, President Donald J. Trump issued over 140 Executive Orders. His Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), originally run by business executive Elon Musk, has been reshaping and reducing the government.

A colleague in Germany wrote to me with puzzlement felt by many in America: “What the hell is going on in the USA?” Yet these disruptions may be just what Republicans intended with 2024 campaign promises to “make liberals cry again.”

While critics raise alarms over the president’s bold moves and supporters think the critics are trying to hem in needed reforms of government, all parties would benefit from understanding the motivations for changes so drastic.

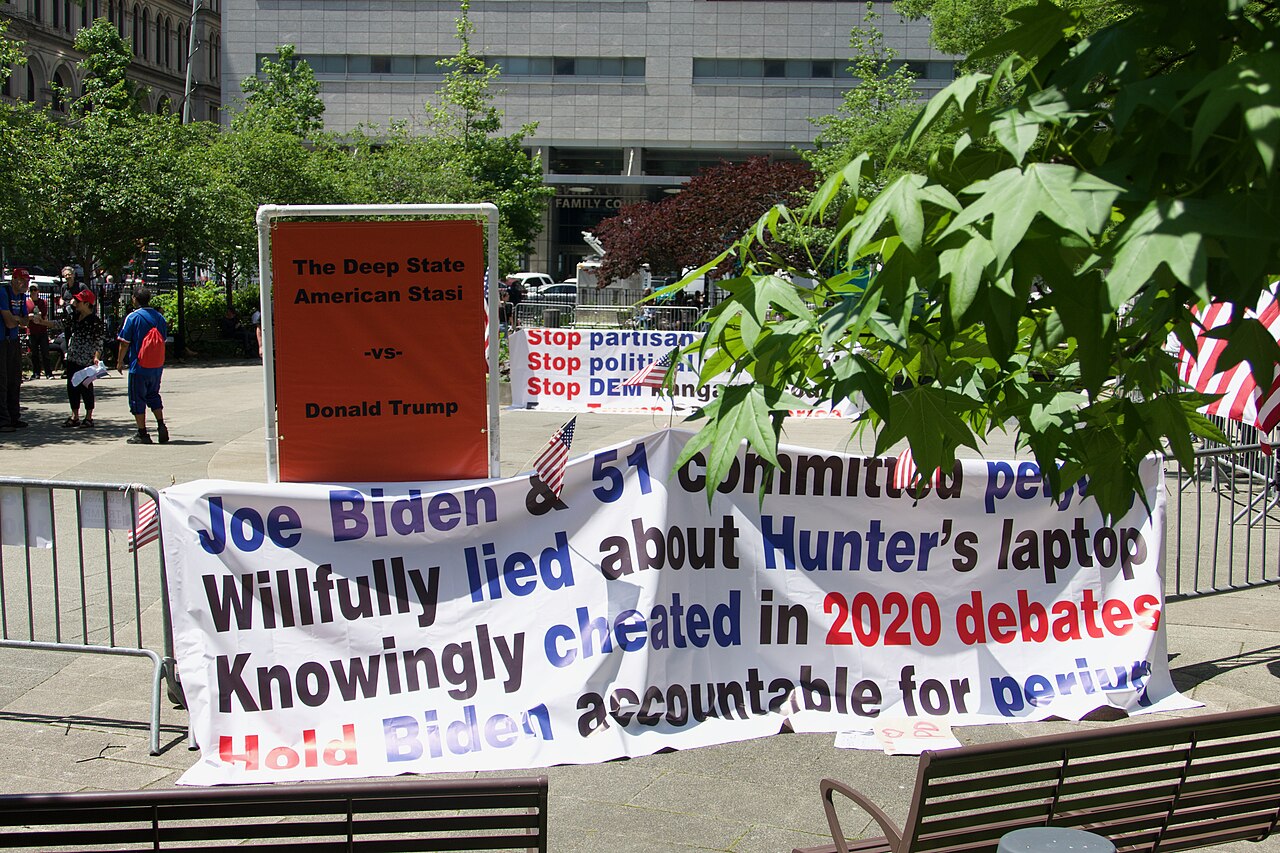

The theory that government has been operating as a “deep state” gone “rogue,” in the words of recent legislation seeking to limit judicial checks on the executive branch, has been motivating Republicans for years.

In 2001, activist Grover Norquist spoke for many conservatives in wanting to “drag … government … into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.”

Half a year into Trump’s second term, his own supporters have become suspicious that even his Justice Department has joined the conspiracy to distract public attention from the “deep state” charge that Jeffrey Epstein organized a ring of elite pedophiles.

Beyond Democratic ridicule of “deep state” conspiracies and Republican satisfaction with their claims to be diagnosing government’s problems, how did these ideas emerge? And what can history of the “deep state” reveal for citizens of either party seeking reform toward a more perfect union?

Fear or Money: Will the Real Deep State Please Stand Up?

Either as a literal subversive plot or as a general irritation with liberals and bureaucrats, recent worry about the “deep state” has strayed from the original meaning of the phrase. The idea of powerful, subversive operatives hidden from public view has included bold charges and shadowy associations, expressed in many variations.

The “deep state” first gained American public popularity in a 2013 novel about “non-government insiders” conspiring to use big money to fund a big arms shipment to big-time terrorists. John Le Carré uses his story-telling skills in his political thriller, A Delicate Truth, to tap fears that just maybe democracy is a sideshow while secretive moneyed interests direct our politics.

The fictional emergence of the phrase followed its use in policy circles to describe the military force used in 1990s Turkey to protect the state from external and internal threats. Similar phrases had circulated in the postwar United States. Understood broadly, these dark words apply to many intelligence operations, criminal organizations, and righteous politicians who skirt public and legal channels to gain power and influence.

In 1955, Hans Morgenthau and George Kennan referred to the American “dual state,” with the growing national security state using modern technology to monitor the public and elected officials. This was managed by what David Wise and Thomas Ross called in 1964 “the secret elite,” which Peter Dale Scott in 2007 showed to be in steady growth without democratic oversight, “outside and above … the public state.”

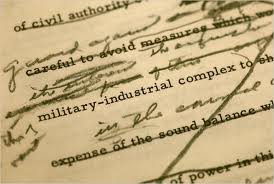

President Dwight Eisenhower added another similar phrase in 1961, the “military-industrial complex,” showing less concern about secrecy than about widespread acceptance of the large and growing “industrial and military machinery” despite its potential for “unwarranted influence” to overwhelm democratic goals for “compos[ing] difference, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose.” Eisenhower focused on the danger of acquiescence with popular acceptance of power outside of elected officials.

These extra-political forces have been enlisted during wars and other emergencies, with suppression of civil liberties—that includes the present with Trump describing immigration as an emergency. This use of force has been justified by claims that brief suspension of freedom would secure the survival of democracy.

But these forces erode democracy with “covert top-down rule,” in the words of Aaron Good. He observes that these militant measures first emerged when fear of Communism justified what he calls “exceptionism” with repeated exceptions to the rule of law.

All these variations on the “deep state” involved intrusions on democracy.

While working as a Congressional staffer, Mike Lofgren witnessed firsthand versions of what these phrases referred to, especially ways that well-funded interests so readily swayed lawmaking.

In 2016, he named his book The Deep State to describe the power of money to shape decisions by members of both political parties. Building on Eisenhower’s warning about normalizing democratic erosions, Lofgren noticed that “the state within a state” was not “a secret, conspiratorial cabal,” but teams of professional lobbyists, “hiding mostly in plain sight.”

Especially with electoral campaigns increasingly dependent on expensive advertising, the loop inside the Washington Beltway had come to include, he observed, candidates spending more and more of their time courting the donations of the wealthy, donors seeking returns on their dollars, and politicians using campaign cash to divert attention from subservience to donors.

Lofgren wrote: “The Deep State [is]…a corporate and private influence network with almost unlimited cash to enforce its will…. Fundamental policy continuity exists regardless of which party controls the levers of government.”

With “Beltwayland” flow of money into politics largely accepted by the public, and resistance marginalized, Lofgren wondered, “Do elections matter?”

The book received limited attention. But in recent years, one side of the Republican Party used the phrase “deep state” as a way to target Democrats, despite Lofgren’s having taken aim at both parties.

Building on generations of Republican antagonism to government, President Trump has sharpened this partisan hostility. He even recently called Democrats “forces of evil.”

He has been presenting the “deep state” not as a threat to the government but as the government itself, embodied in administrators, supported by the Democratic Party, motivated by liberal ideology, and with “radical … Marxist” intentions, showing a lumping of all leftists with the most extreme. Previous critics of government had called the system bad; with “deep state” thinking, government workers themselves are the enemy, along with his political opponents.

Previous critics of government had called the system bad; but with “deep state” thinking, government workers themselves are the enemy, along with political opponents.

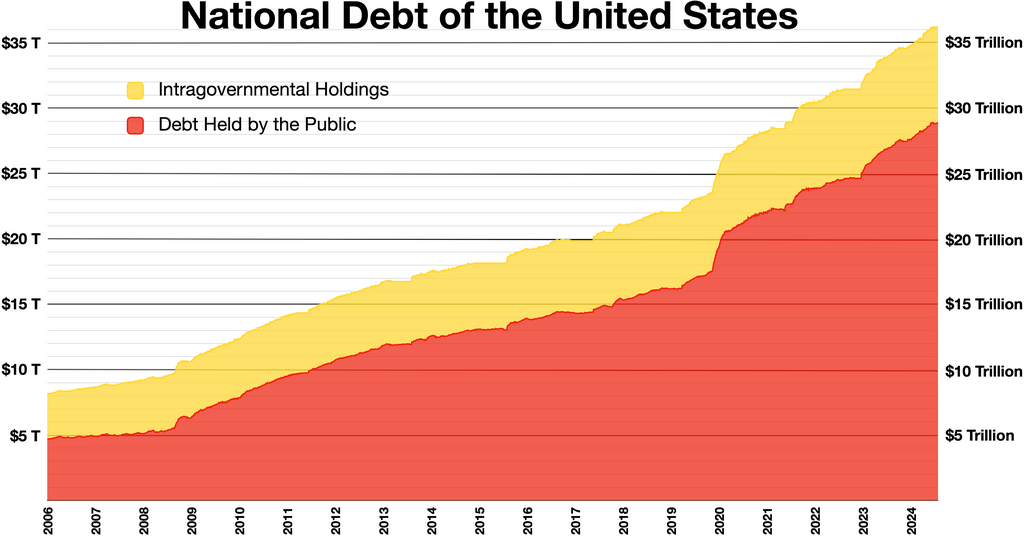

Beneath the public worries about rogue bureaucrats tampering with cultural norms and the ideological hopes for shrinking government, the deep policy problem motivating “deep state” thinking is the national debt, now over $34 trillion, more than a fifth higher than the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), with payments on the debt the fastest growing line item in the federal budget and those costs exceeding money spent on national defense, Medicare, or Medicaid. As a result, Moody’s credit rating agency downgraded the United States’s credit rating.

By contrast, supporters of government workers devote less attention to the debt while praising the good work of civil servants responding to social complexities with nonpartisan public problem solving.

While Republicans worry more about the debt, they rarely consider savings from government spending on the military. Neither party supports cutting Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid, which make up half the budget, although the 2025 Republican budget bill includes significant cuts to Medicare spending.

Lofgren himself maintains that “societies create bureaucratic structure to solve problems.” He critiques both Republican “deep state” thinking and Democrats opposing it without attention to spending soaring into large debt. Of course, in recent times these roles have changed, and the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the recent Republican “big, beautiful bill” will add $3.3 trillion to the national debt.

Both following and fighting the current use of the phrase have amplified polarized distraction from Lofgren’s concern about monied interests shaping public thinking and political policies.

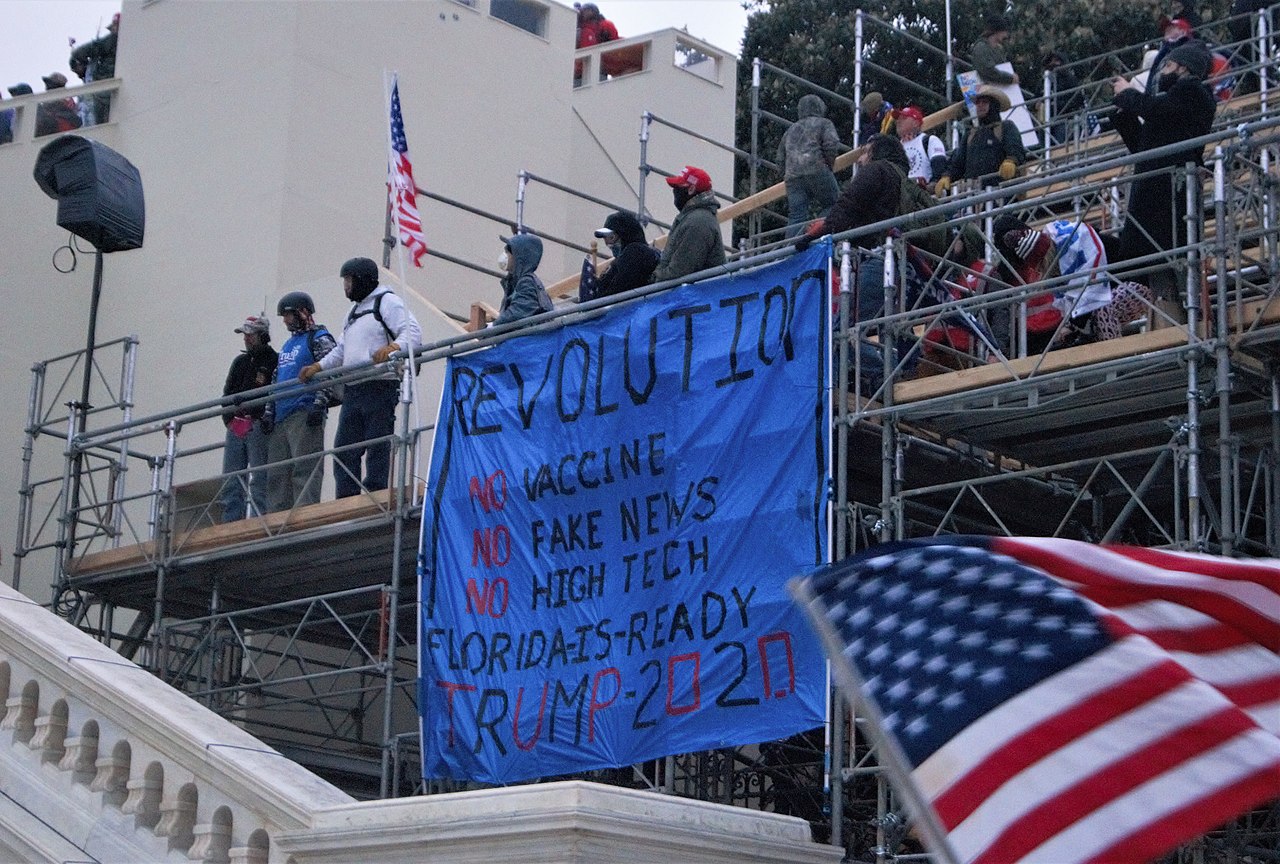

During his first term, Trump portrayed the threats to be society-wide in declaring that “unelected deep-state operatives” have allies in the “Fake News Media,” his dismissive phrase for mainstream news sources.

Campaigning in 2024, he amplified his critique into a blunt promise: “We will demolish the deep state.” And in his first address to Congress on March 6, 2025, Trump declared, “The days of rule by unelected bureaucrats are over.”

“Deep state” thinking is a primary motivation for the enormous cuts in government programs embodied in Musk’s chainsaw. The speed and intensity of the changes has left Democrats scrambling to protect programs in the face of public impatience with government and institutions in general, sentiments also motivated by “deep state” thinking.

Cultural Resentments: Seeds of Vengeance

In his second administration, the president has adopted wartime footing with attempted legal justifications based on emergencies for his executive orders. As a candidate, he had already telegraphed his punches, as boxers say. He attacked the press as the “enemy of the people” and called Democrats an educated elite while paying little attention to the power of the nation’s financial elite.

This message rings true with many voters, and its populist appeal targets (some of) the upper class as culprits for explaining how the rich have gotten richer in the past few generations. In a reversal of decades of party identification, higher percentages of the wealthy and well educated now vote for Democrats while larger numbers of the working class with limited education now vote for Republicans.

And sure enough, since the 1970s, the well-off and the educated command a larger share of citizen net worth. For many in the working class, the prosperity of educated professionals is a larger irritant than the still-more-prosperous owners of businesses, even the richest among them.

The public little critiques billionaires who mostly gain their wealth in business, even as their holdings increased by 14% last year, according to Forbes, up to $16.1 trillion. Four of them are members of the Trump administration—in addition to the president himself. But businesspeople provide jobs (or can take them away) for average citizens, while professionals engage in analysis without tangible production.

With power concentrated in the private sector, leading businesspeople have been dramatically impacting working-class lives with jobs lost to automation or with factories relocated overseas. As a result, many workers have been “rendered economically useless,” as Gene Ludwig observes in his research on low-income Americans, or their skills require upgrades with more professional training.

Those on the losing end of fewer opportunities are particularly irked by the “prevailing economic analysis” displaying that “the economy is humming” according to aggregate data about high national gross domestic product (GDP) and low unemployment statistics.

Yet as Ludwig found, this information reflects the successes of the well off but only “a sliver” of the experiences of those struggling. The unemployment figures do not capture the hurts and humiliations of those moving to lower-paying jobs or working part-time.

Ludwig suggests that “continued dependence on aggregate U.S. economic data is clouding our understanding of what’s happening on the ground.”

Political theorist Jason Blakely warns that this gap between analysis of markets and lived experience contributes to “runaway inequality” that threatens democracy.

He suggests that confidence in data stems from treating modern economics as “social physics.” Economic conclusions are given unquestioned social authority, with confidence, as Nobel-Prize winning economist Gary Becker insists, that the analysis provides a “framework for understanding all human behavior.”

The public faces of these scientific certainties are educated professionals, including many in government offices, generally working in a spirit of public service with a democratic ethos.

As Blakely points out, “we need the information generated by social scientists,” even as their work can be used with little attention to their own ideological assumptions or to the limits of their powers. He calls this “the problem of scientism,” involving an “unwarranted confidence in the power of science to explain all of human life.”

The resulting gap between the data of professional inquiries and the experiences of workers breeds resentment, especially when administrative policies support progressive causes that challenge traditional values. And professionals’ high level of education and use of intellectual discourse can seem patronizing to workers. This has contributed to anger and shame among the less educated, as Arlie Russell Hochschild observes.

While paying little attention to business complicity in reduced job opportunities, Republicans talking about the “deep state” speak to resentments directed at the educated elites as objects of suspicion.

With social opportunities shrinking for many in the working class and many educated professionals not experiencing those problems, Trump argues, with limited evidence, that elitist Democrats have been using the tools of government to promote liberal goals and the tools of law enforcement as “lawfare” for “political prosecutions” of Republicans.

With the fictional and bipartisan origins of the “deep state” now largely forgotten by both parties, Republicans focus on what they call the government overreach of Democratic policies with little recognition of ways they have actually helped the working class.

Meanwhile, many Trump supporters show little worry about his own membership in the financial elite. His promise of angry retribution against his supporters’ enemies grants him a position for many voters as “our elite” among the powerful to serve as avenging tribune for their anger.

Meanwhile, few Republicans or Democrats acknowledge their own roles in the shadow government allowing big money to shape policies.

Deep State or Public Purposes: End, Defend, or Mend Government Programs?

The Trump administration’s plan to target Democratic agents of the “deep state” may find some examples of partisan corruption. That civic purpose does not need the flamboyant promise of the new Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Kash Patel, to “shut down the FBI Hoover Building … and reopen it … as a museum of the deep state.”

And the administration shows no impulse to direct its righteous goals in bipartisan ways, despite the original meaning of the “deep state” phrase. Even Democratic efforts to combat “deep state” conspiracies distract attention from the power of money overriding people power, just as Le Carré and Lofgren warned.

Trump administration policies, including moves to concentrate power, stem from absolute judgments against government programs, a wholesale hostility in keeping with their “deep state” thinking. And their speed and drama have prompted similar either-or responses from Democrats rushing to defend programs.

The Supreme Court has stepped beyond the political contest with focus on the very purpose of government programs. They asked the president to “clarify what obligations the government must fulfill.”

But in public, there is little discussion of government’s purposes, much less about the challenge of addressing those purposes within existing revenue streams—that is, how to square them with growing debt. The nation would benefit from some crucial questions for Republicans, now holding so much power:

Dear Republicans, are you against government methods for addressing the goals of its programs, and if so, how would you achieve those purposes through other means? Do you have alternative approaches in mind to achieve those goals?

Or are you against those public goals themselves, ranging from the oversight work of inspectors general to funding of foreign aid, and many more? With your hostility to government workers, are you also against those government purposes?

The nation would also benefit from a few key questions for Democrats:

Dear Democrats, your defense of particular government programs has been impressive, but then how would you deal with the expenses of government in total, especially with the large annual deficit spending of the last few years and projected to continue?

Would you consider reducing funds for programs in domestic life or for America’s global role; or would you consider raising more funds to pay for them? Or do you consider the national debt to be an insignificant or manageable problem?

Each polarized party shies away from these questions for fear of revealing weakness in their paths to power. Yet any versions of these questions circulating among citizens would prod the parties to serve as resources rather than only as citadels for fighting in polarized opposition.

Recent polarization through speed has left little room for consideration of potential ways to reduce the debt without loss of purpose or for scrutiny of potential problems in programs that could be improved.

Instead, the pace of change has produced a politics of Team Vanquish Deep State! lined up against Team Defend Government as It Has Been!

That amplified polarization draws citizens into joining one side, with dire visions of the other side (sometimes justified), but with little attention to the potentially valid questions that may circulate (even just in part) beneath the antagonisms.

With fights over big government, neither party is paying attention to problems with big money, the central warning behind earlier uses of the phrase, the “deep state.”

Could the dramatic if not chaotic actions of Republicans serve as a wakeup call for reform? Candidate Trump effectively diagnosed an impatience with government. Bill Clinton was adept at feeling the pain of voters; Trump is adept at feeling their anger.

But much of that anger comes from frustration with polarization, which has been keeping both parties in what Lee Drutman calls the “doom loop” of gridlock, preventing the tackling of many major problems.

President Trump has been implementing prescriptions with unprecedented harshness and destruction of many public purposes, and polls show that most Americans do not approve, even among his own constituents.

Long postponement of ways to break through polarized standoffs has effectively invited his extreme path. Perhaps these dire current conditions can prod both sides to own up to the role of money in politics and to mend government programs rather than ending them.

The backlash against the severity of DOGE indicates a groundswell of public outrage that could grow into support for action—by members of either party—both to gain support for vital government programs and to reduce the national debt.

A voice from one of the slashed programs, the Agency for International Development (USAID), points to possibilities in this direction.

For years at the agency, Sean Brooks dispensed aid and good will in Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan, but also recognized “agency missteps.” Rather than simply issuing its “death blow,” he welcomes addressing those problems to improve “America’s role as a global humanitarian leader… serving America’s interest abroad.”

The current talk around the “deep state” has been dramatizing political fights but reducing abilities to achieve national goals and address problems effectively.

Ironically the fights over cuts have turned the whole political arena into Scenes of Divisions Over Polarized Inefficiencies (with an acronym to match, So DOPI). Michigan Democratic Senator Elissa Slotkin, responding to Trump’s speech in Congress, acknowledged his themes in saying, “America wants change,” and “we need more efficient government,” even adding, “I’ll help you do it.”

Can a critical mass of Republicans take up versions of her proposition that “change doesn’t need to be chaotic or make us less safe.” Democrats or Republicans can take first steps in this direction by connecting “deep state” worries to its earlier meaning.

Hey, Elected Representatives, Get to Work on the People’s Business

The temptation to use the democratic processes to justify limits on freedom lurks now, as it has in every era, whenever people feel afraid, with their security threatened. However, reclaiming the original meaning of the “deep state” can still appeal to the deep-seated American taste for freedom—in this case, freedom from money’s manipulations, with freedom for citizens to vote their consciences rather than as echoes of powerful interests.

The founder of American psychology, William James, would say that this can emerge if freedom can gain more attention than security. The key will be for the song of freedom to ring louder than the siren calls of fear.

To borrow from Ray Parker, Jr.’s Ghostbuster song, most American voters in 2024 decided that “there’s something [wrong in their national] neighborhood… something weird and it don’t look good.” A slim plurality voted for the party that most fully diagnosed that feeling.

The history of “deep state” thinking sheds light on how we’ve gotten to current enormous changes and can light our way about choices for next steps. The immediate future belongs to the Republicans in power and presenting a conspiracy version of the “deep state.”

The long-term future belongs to politicians who can address problems deeper than “deep state” stories without squelching freedom. There will be power in speaking out both for the eroding status of the working class and for the rights of those facing discrimination.

Freedom can best ring with reduction in reasons to be afraid and with increased reasons for citizens to believe that their votes are not being hijacked by big money.

Better than banishing “deep state” thinking and more powerful than ridicule of its literal tenets would be drying up reasons for people to feel the fears that make its worries plausible. Members of both parties could stand up to Beltway benefits for the wealthy that have been hemming in all those out of power.

Substantial support for American freedom is the best prescription to offset slides into short-term security. Then in place of worrying about the conspiratorial “deep state,” Americans can rally for support of deep reductions in the role of money in politics—and that applies to both parties.

Blakely, Jason. We Built Reality: How Social Science Infiltrated Culture, Politics, and Power. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Department of State v. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition. Supreme Court of the United States. 24A831, 2024, https://www.scotusblog.com/cases/case-files/department-of-state-v-aids-vaccine-advocacy-coalition/.

Drutman, Lee. Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. “Farewell Address.” January 17, 1961. National Archives. Updated July 15, 2024, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/president-dwight-d-eisenhowers-farewell-address.

Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, eds. “Executive Orders.” The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara, CA, 1999-2025, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/323876.

Goldberg, Zach. “The Rise of College-Educated Democrats.” Manhattan Institute. February 2, 2023, https://manhattan.institute/article/the-rise-of-college-educated-democrats.

Good, Aaron and Peter Phillips. American Exception: Empire and the Deep State. Skyhorse, 2022.

Hiramoto, KJ. “Bill Aimed to Restrict ‘Activist Judges’ Awaits Senate Vote; Critics Call HR 1526 a Threat to Constitution.” Fox 11 Los Angeles. April 15, 2025, https://www.foxla.com/news/hr-1526-trump-bill-restrict-court-judge.

Hochschild, Arlie Russel. Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right. The New Press, 2024.

James, William. The Principles of Psychology, vol 1. Henry Holt and Company, 1918.

Joseph, Jamie. “‘Political Prosecutions’: Republican AGs Demand End to ‘Lawfare’ Prosecutions of President-Elect Trump. Fox News. November 15, 2024, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/political-prosecutions-republican-ags-demand-end-lawfare-prosecutions-president-elect-trump.

Le Carré, John. A Delicate Truth. Penguin Books, 2013.

Licon Gomez, Adriana. “Musk Waves a Chainsaw and Charms Conservatives Talking Up Trump’s Cost-Cutting Efforts.” AP. February 21, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/musk-chainsaw-trump-doge-6568e9e0cfc42ad6cdcfd58a409eb312.

Lofgren, Mike. The Deep State: The Fall of the Constitution and the Rise of a Shadow Government. Viking, 2016.

Ludwig, Gene, ed. The Vanishing American Dream: A Frank Look at the Economic Realities Facing Middle- and Lower-Income Americans. Disruption Books, 2020.

Marsden, Emma. “What Kash Patel Has Said About the FBI.” Newsweek. December 1, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/what-kash-patel-has-said-about-fbi-1993764.

Morgenthau, Hans J. and George F. Kennan. “The Impact of the Loyalty-Security Measures on the State Department.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 11 no. 4 (April 1955): 134-140, https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1955BuAtS..11d.134M/abstract.

Nelson, William E. “The Shutdown: Drowning Government in the Bathtub.” The Conversation. February 12, 2019, https://theconversation.com/the-shutdown-drowning-government-in-the-bathtub-111333.

Orlando, Joyce. “What is Trump’s Approval Rating Now? Polls Show a Decline as He Approaches 100-Day Mark.” USA Today. April 28, 2025, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2025/04/28/donald-trump-approval-rating-latest-polls-decline-100-days/83326990007/.

Ortega, Bob and Kyung Lah, Allison Gordon, and Nelli Black. “What Trump’s War on the ‘Deep State’ Could Mean: ‘An Army of Suck-Ups.’” CNN. April 27, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/04/27/politics/trump-federal-workers-2nd-term-invs.

Peterson-Withorn, Chase. “Forbes’ 39th Annual World’s Billionaires List: More Than 3,000 Worth $16 Trillion.” Forbes. April 1, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/chasewithorn/2025/04/01/forbes-39th-annual-worlds-billionaires-list-more-than-3000-worth-16-trillion/.

“President Trump: Unelected Deep-State Operatives Threat to Democracy Itself.” CBS News Texas. September 7, 2018, https://www.cbsnews.com/texas/news/deep-state-operatives-threat-to-democracy/.

“Read the Full Transcript of Slotkin’s Democratic Response to Trump Speech to Congress.” CBS. March 5, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/transcript-slotkin-democratic-response-trump-2025/.

Samuels, Brett. “Trump Ramps Up Rhetoric on Media, Calls Press ‘the Enemy of the People.’” The Hill. April 5, 2019, https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/437610-trump-calls-press-the-enemy-of-the-people/.

Scott, Peter Dale. The Road to 9/11: Wealth, Empire, and the Future of America. University of California Press, 2007.

Schaeffer, Katherine. “6 facts About Economic Inequality in the U.S.” Pew Research Center. February 7, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/02/07/6-facts-about-economic-inequality-in-the-u-s/.

Tankersley, Jim. The Riches of This Land: The Untold, True Story of America’s Middle Class. Public Affairs, 2021.

Tierney, Abigail. “National Debt of the U.S.: Statistics and Facts.” Statista. July 29, 2024, https://www.statista.com/topics/836/national-debt-of-the-us/#topicOverview.

Wise, David and Thomas B. Ross. The Invisible Government. Random House, 1964.

Zanona, Melanie, Jonathan Allen, and Matt Dixon. “House Republicans Hit the Brakes on Town Halls After Blowback Over Trump’s Cuts.” NBC. February 25, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/house-republicans-town-halls-blowback-trump-cuts-rcna193766.