Among the first actions of the Trump administration was the suspension of funding for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID. Since its creation the Agency has had both supporters and critics. In this article, historian Amanda McVety explores the history of USAID to examine its role in fostering both international development and American foreign policy interests.

On Friday, March 28, 2025, the Trump administration released plans to reduce the staff of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to 15 people and move it fully under the control of the State Department.

The agency had employed over 10,000 people in the beginning of 2025, still working in the name of the commitment that President John F. Kennedy had made in 1961 “to establish a new and more effective program for assisting the economic, educational and social development of other countries and continents.”

We are going “to help them help themselves,” he had promised in his inaugural address, “for whatever period is required—not because the Communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right.”

As we are faced with the end of USAID, it seems an opportune moment to go back to its beginnings and consider the internationalist impulse that drove the U.S. commitment to fight misery and poverty in other places.

Decolonization, Cold War, and International Aid

Distributing foreign aid for development was not a new idea in 1961. The United States had been doing it for years, but Kennedy believed it had not been doing it well.

In preparation for his presidency, he organized a task force to investigate the foreign aid bureaucracy. The group grimly reported that the existing program was “not suited” for the moment. It was not big enough or bold enough; it had “been designed primarily as an instrument against Communism, rather than for constructive economic and social advancement,” and it was not developing much at all.

Meanwhile, the Soviets had gotten better at foreign aid over the course of the 1950s and more countries were turning to Moscow for the assistance they were not getting from Washington.

The situation was dire, Secretary of State Dean Rusk told Congress a few months later: the Cold War had turned “from a military problem in Western Europe to a genuine contest for the underdeveloped countries.” U.S. foreign aid needed a redesign to meet the moment. What was needed, a White House working paper explained, was “to replace our term insurance with an endowment policy.”

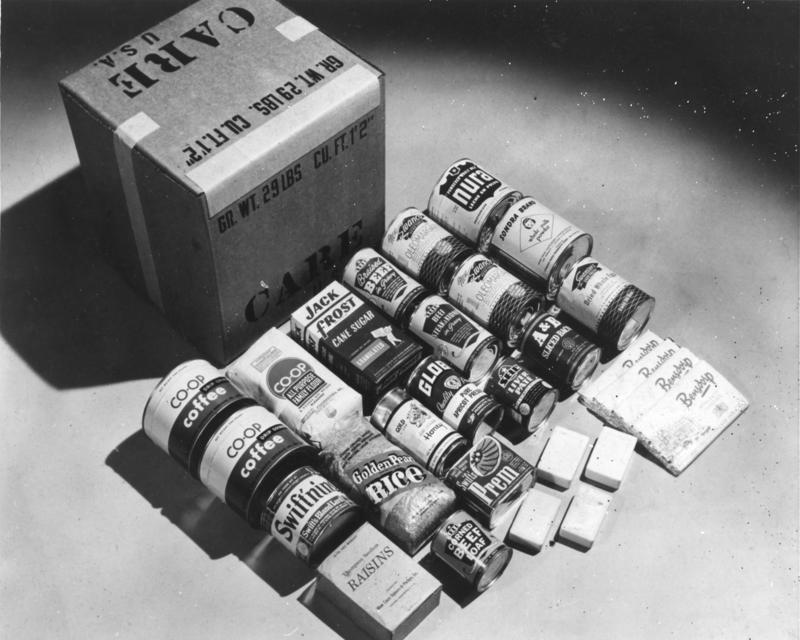

The “term insurance” then in place was administered via the efforts of several agencies, most notably the Food for Peace Program and the International Cooperation Administration (ICA). Eisenhower had created Food for Peace (commonly known as PL-480) in 1954. It set up a permanent program for the government and voluntary/religious organizations to ship domestic food surpluses to countries struggling with food insecurity.

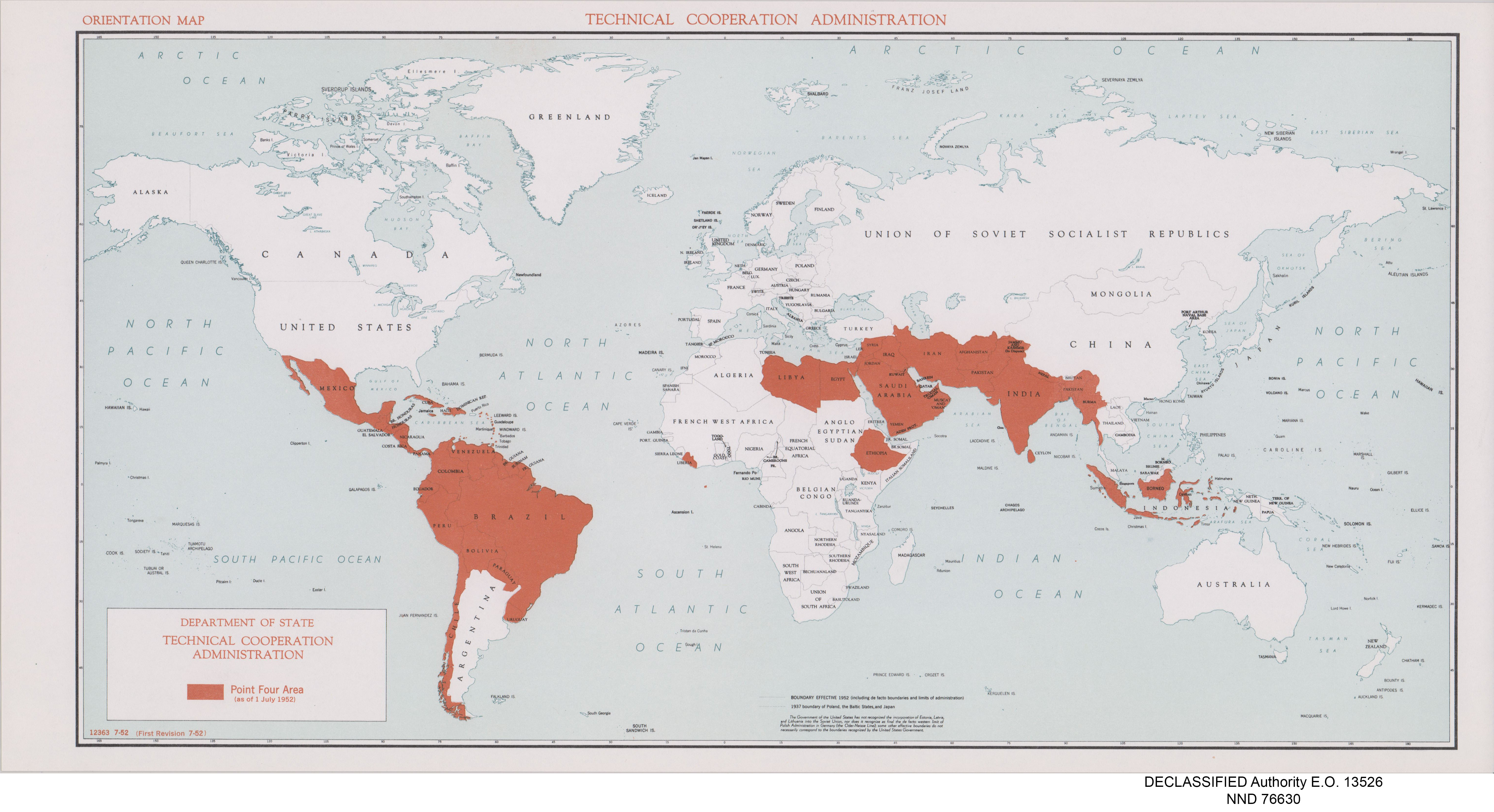

The ICA was a new name for agencies that went back to a Truman administration initiative popularly known as Point Four in reference to its origins in Truman’s 1949 inaugural address.

The U.S. effort to build “a world in which all nations and all peoples are free to govern themselves as they see fit, and to achieve a decent and satisfying life,” Truman had warned in the speech, was opposed by a regime “with contrary aims and a totally different concept of life.”

The United States will thwart Soviet ambitions, he continued, in part through “a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas.” These programs would be developed out of communism’s reach.

Belief in the transforming power of “development” was one of the defining characteristics of the 20th century. It had roots that stretched back to 18th-century ideas about progress but took its modern shape in the aftermath of World War I. The war inspired humanitarian action on a previously unimaginable scale. It also sparked a rapid increase in expectations of living conditions.

The League of Nations played a significant role in spreading faith in development throughout the 1920s and 1930s. It sponsored technical missions and sent experts in health, nutrition, education, labor, and more around the world to collect data on how people were living. They found wide disparities.

A growing number of economists joined the effort, compiling historic and contemporary data. They found even more disparities, but also hope, for it seemed to them that the data showed a clear path forward via economic growth. A poorer economy could be turned into a richer one via the right mix of foreign capital and expertise. An economy could be “developed.”

The pursuit of economic growth gained greater attention in the 1930s as governments scrambled for paths out of the Great Depression. Colonial officials had already begun adopting the language of development in the 1920s, but now they seized on the idea of fostering economic growth in the colonies via capital investment and technical assistance to enhance prosperity at home.

Such methods were particularly appealing to Britain and France with their expansive empires, but they were joined by an increasing number of other countries that viewed national economies as parts of a larger whole. The Depression had made the point. In 1939, the economist Eugene Staley announced “the era of a planetary economy” but that nationalism was threatening its disintegration.

World War II heightened the stakes while it turned development into a tool of foreign policy. American officials argued that New Deal modernization was universally applicable and offered a better path forward than the authoritarian modernization pursued by Germany, Italy, and the USSR.

They looked first to Latin America to prove it. The 1933 Good Neighbor Program called for development via capital investment and technical assistance to shut down the Axis encroachment into the hemisphere and to advance relations with Central and South American countries.

But why stop there?

When Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Winston Churchill in August 1941 to discuss the war, they announced hope of ultimately securing a peace that promised that “all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.”

The language drew directly on a speech FDR had given earlier in the year, when he had noted that Americans now demanded of their government “the enjoyment of the fruits of scientific progress in a wider and constantly rising standard of living,” and they were not alone.

Roosevelt, in particular, was convinced that Allied plans had to include strategies for getting liberated people “relief and rehabilitation.” Once the United States was officially in the war, it worked toward this goal. The Allies created the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency and, as the devastation of the war became clearer, they added “reconstruction” to their list of tasks.

Then, at the urging of leaders from around the world, they added “development.” Officials wrestled over the meanings and requirements of these words in publications and at conferences designed to build the bureaucratic machinery of the postwar world.

At Hot Springs, Bretton Woods, Dumbarton Oaks, and beyond, representatives constructed new permanent international agencies tasked with securing the anticipated peace via shared economic progress.

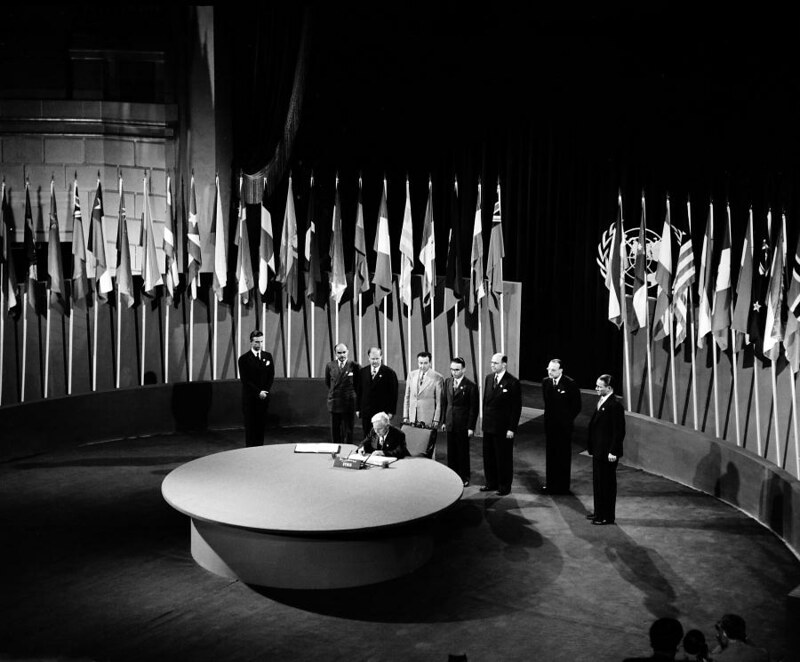

When they ratified the Charter of the new United Nations in 1945, the founding members promised “to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples.” Development became an official UN goal. War was declared on poverty and misery, at first to ward off the return of fascism.

As the divide between the United States and the Soviet Union grew, development was given a new purpose. Officials on both sides of the Iron Curtain turned to development as a means of proving that their vision of modernity was the correct one. Therein lay the origins of Truman’s “bold new program.”

By the end of 1952, Point Four aid was going to 35 countries. The budget was modest (only $148 million in FY 1952), but it was enough, Truman argued in his memoirs, to set those nations “on the path of rising living standards by their own efforts and by the work of their own nationals.”

The Eisenhower administration was less convinced. It tried to shake the “Point Four” label with name changes and increasingly favored military over economic assistance.

But faith in development did not disappear.

Shut out of power in Washington, a group of liberal intellectuals spent the 1950s writing books and building new academic departments dedicated to the study of development. In doing so, they pulled the field away from economists, bringing in anthropologists, sociologists, political scientists, and others to foster new conversations about the causes of and the solutions for poverty, both at home and abroad.

They discovered, one wrote in 1965, that development required more than foreign capital and technical assistance; it “required the modernization of entire social structures and ways of thoughts and life.”

When Kennedy won the White House in 1960, he brought these modernization theorists with him to Washington.

Kennedy and “The Development Decade”

Kennedy’s development vision was expansive to try to meet the requirements of the moment. Decolonization was proceeding apace, opening the door to Soviet incursions into the new nations struggling for freedom across Asia and Africa. They all wanted development, and Moscow promised that its economic and political model was the best path forward.

Kennedy warned that the United States needed to demonstrate the opposite, and the existing machinery of aid was not up the task.

In a report that February, John Kenneth Galbraith wrote that many nations “including some heavily aided ones,” have made no “appreciable advance” in the last 12 years, primarily because “economic aid does not deal with decisive barriers to development—these being illiteracy, lack of an educated elite, inimical social institutions, no system of public administration, a lack of any sense of purpose.”

Meanwhile, the Soviets were offering plans that promised to tackle all those issues. Kennedy asked Congress for a five-year commitment for a new “program of social and economic development” to launch “a decade of development on which will depend, substantially, the kind of world in which we and our children shall live.”

Congress passed the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 in September, and Kennedy created USAID.

As FDR had done before him, Kennedy turned first to Latin America, creating the Alliance for Progress, a ten-year, $20 billion USAID-directed program. Funding came with liberalization requirements designed to turn “traditional” societies into “modern” ones.

The top-down vision of transformation that modernization theory espoused, however, proved ripe for corruption. It put significant power into the hands of the leaders of recipient nations, who had their own visions of what modernization should look like in their countries.

The Kennedy administration increasingly found it easier to work with authoritarian and military regimes than against them and muffled calls for democratic reform in Latin America and beyond.

The Johnson administration largely did the same, and the results were not necessarily good. Projects became tangled in the violence those regimes perpetrated and less connected to conditions on the ground. It was a troubling turn.

In 1968, President Johnson charged USAID to produce a report on its accomplishments. Agency staff wrote that “despite many important development successes, we have experienced a steady decline in the political and public support of the foreign aid program.”

Congress had gradually decreased the budget—from $3.9 billion in 1962 to $2.2 billion in 1968—while increasing its demands for results. “No one was prepared to conceive of the effort as one of decades,” the report continued, but modernization took time.

USAID claimed successes in Korea, Greece, Iran, Israel, Brazil, India, Turkey, Pakistan, and Taiwan during the development decade, but the gap between the poorest of the poor and the West did not shrink.

Africa was the hardest hit region, but the largest USAID mission was in Vietnam.

The Johnson administration had been hopeful that development in South Vietnam would win popular support for the regime, but war and political corruption in Saigon had sown widespread suspicion. Hostility instead, and not just in Vietnam.

Voices of dissent shouted from all quarters, and the Development Decade ended in anger and demands for change.

Aid and International Inequalities

The nature of that change became clear in 1973. That year, Robert McNamara, who had been the U.S. Secretary of Defense and was now the president of the World Bank, argued for a focus on “the poorest of the poor.” The situation was dire, he reported, and the entire international development community needed to change its approach.

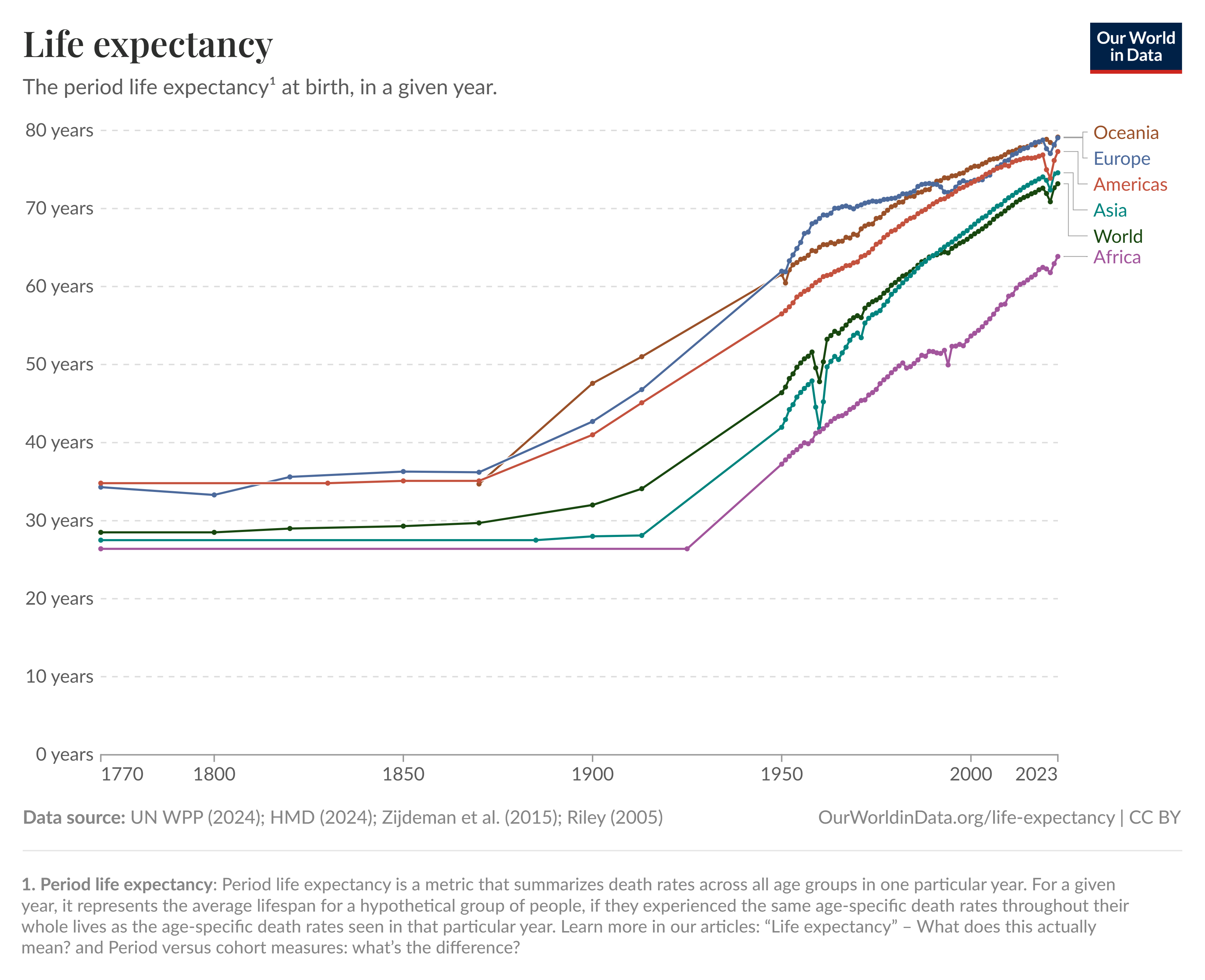

Over 40% of people in developing nations lived in “absolute poverty” with an average life expectancy 20 years shorter than those of people in affluent countries. Most of them lived in rural areas.

While poor regions suffered, affluent nations maintained protectionist trade restrictions on agricultural imports from poorer nations that cost them billions in potential revenue.

McNamara particularly targeted Americans in his rebuke, noting that although only 6 percent of the world’s population, they consumed about 35% of its total resources. Yet, the United States only ranked “fourteenth among the sixteen developed nations” in the percentage of its GNP going to foreign economic assistance.

The U.S. government made some of the changes McNamara urged in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1973, which said that funding should focus on the poorest of the poor via programs in food and nutrition, population control, health, education, and human resource development. The act also limited the use of funding for military purposes or police training and stressed the importance of integrating women into development programs.

The reforms of 1973 were an earnest attempt to move away from the top-down, authoritarian-supporting programs of the 1960s by focusing on the needs of the rural poor. The agency began to increase its reliance on other entities—including nongovernmental organizations, the World Bank, and others—for administration of the aid.

The international aid community grew larger and more diverse.

Dissent grew in turn as groups argued over why the gap between the wealthiest and poorest countries had continued to grow despite decades of development assistance.

Many argued that this proved that there had not been enough aid and/or that it had been distributed incorrectly; some argued this proved that aid itself was a problem; others argued that the agricultural subsidies affluent nations paid their famers negated the value of the aid that those same countries provided the Global South.

Whatever the reason, poverty proved harder to eradicate than the earliest proponents of foreign aid had imagined. The staff of USAID soldiered on, looking for ways to make a difference but frustrated by bureaucracy that slowed their ability to act.

The end of the Cold War inspired hope for a truly united global effort to improve people’s lives. Attention turned to the United Nations for leadership in the effort.

In 1990, the United Nations Development Programme established the Human Development Index, aiming to expand the understanding of progress beyond simply economic growth by looking at life expectancy, education, and Gross National Income per capita.

Development was now understood to mean giving people throughout a country more options and opportunities. Changing how development was measured helped change how it was pursued. In 2000, the UN adopted the Millennium Development Goals, which committed world leaders to combating poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation, and discrimination against women.

The UN reported in 2015 that the goals stimulated a renewed push for development; foreign aid for development increased from about $81 billion in 2000 to $134 billion in 2014, or 0.3 percent of the gross national income of developed countries. Beyond aid, there were also efforts to make trade fairer and to help countries reduce their debt burdens.

The progress inspired a renewed commitment to internationalism in 2015.

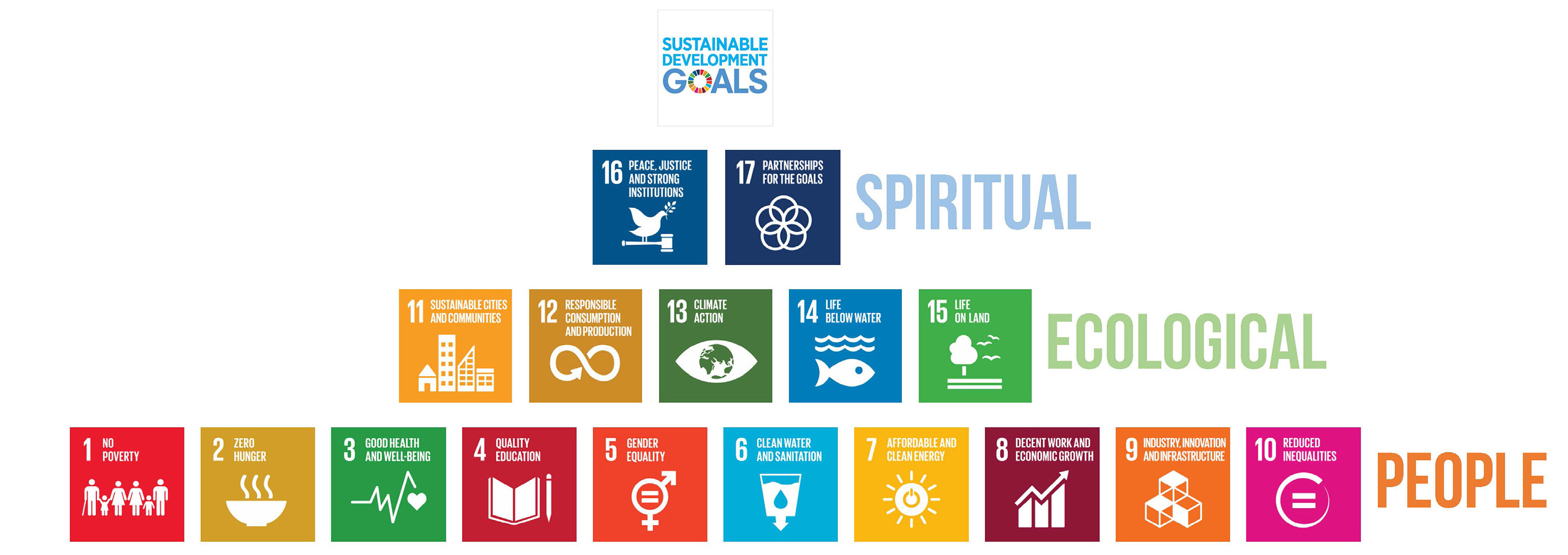

That year, the international community adopted agreements on climate change, disaster risk reduction, financing for development, and 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), asserting “that ending poverty and other depravations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth—all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.”

USAID participated in this effort, notably increasing funding for public health initiatives, education, and disaster relief.

The work mattered—particularly in Africa. In its 2019 report on the SDGs, the UN noted, “extreme poverty has declined considerably, the under-5 mortality rate fell by 49 per cent between 2000 and 2017, immunizations have saved millions of lives, and the vast majority of the world’s population now has access to electricity.” Lives improved in measurable ways and optimism increased.

Then came Covid-19.

The Human Development Index value fell for the first time ever in 2020. It did so again in 2021. The pandemic derailed development, and it has proven difficult to get things back on track. After 20 years of steady success in closing the gap between the world’s richest and poorest nations, the trend is now in reverse.

The Future of Aid and Development

There are many reasons to be skeptical about bilateral foreign aid. Far too often over the decades, efforts to promote development gave way to the geopolitical ambitions of both the donor and the recipient governments, often to the detriment of the people who were supposed to be helped. Pots of USAID money often supported the personal projects of ambassadors and politicians for their own political purposes.

Even when aid was designed to raise people’s standard of living, it didn’t always work. USAID’s bureaucratic structures were notoriously cumbersome and needed revision.

But considering everything the Trump administration is doing, it seems clear that killing the agency is not an act of reform, but part of a larger rejection of the internationalist impulse that drove Americans in the past to value a stronger, healthier global community.

The history of foreign aid provides many examples of failed projects and disappointed hopes, but it also provides multiple examples of notable successes, particularly in the fields of global health and disaster relief.

According to Our World in Data, global life expectancy rose from 46.4 in 1950 to 73.2 in 2023. Multiple factors played a role in that stunning accomplishment, including aid-supported health programs. They work. The estimated share of children around the world who die before age 5 has plummeted from 22.7% in 1950 to 3.6% in 2023. Improvement happened everywhere, even in the world’s poorest nations, and these programs must be sustained to keep working.

They do so at a comparatively low cost to American taxpayers. USAID dispersed $43.8 billion in the last fiscal year, which added up to only 0.7% of the federal budget. That total included 73% of all U.S. global health bilateral assistance.

That assistance helps Americans while helping people around the world, in part through contracts with U.S. companies, but also because health concerns stretch across borders (as the pandemic made abundantly clear). So, too, do instability and war.

It is still in our best interest today to build a healthier, more equitable world, just like it was in 1961.

Sheyda F.A. Jahanbani, The Poverty of the World: Rediscovering the Poor at Home and Abroad, 1941-1968 (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Julia F. Irwin, Catastrophic Diplomacy: US Foreign Disaster Assistance in the American Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2024).

Stephen J. Macekura and Erez Manela, Ed. The Development Century: A Global History (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Daniel Immerwahr, Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development (Harvard University Press, 2015).

Eric Helleiner, Forgotten Foundations of Bretton Woods: International Development and the Making of the Postwar Order (Cornell University Press, 2016).