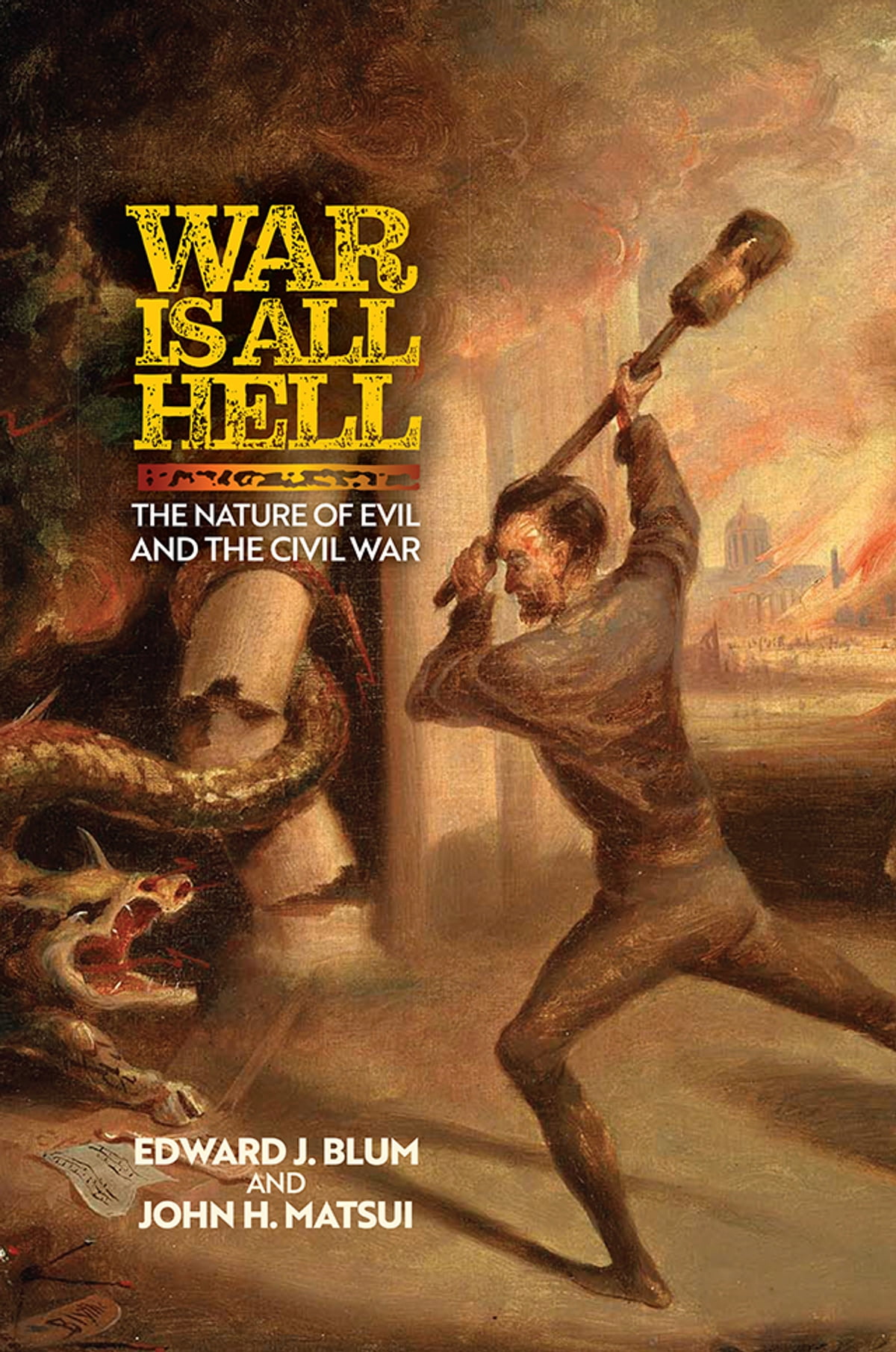

In War Is All Hell Edward J. Blum and John H. Matsui argue that Americans living through the Civil War era and its immediate aftermath made sense of the conflict using Christian ideas of evil. This work is partly a response to scholarship that the authors believe has overemphasized the role of “the forces of good,” usually represented by God and Jesus, in interpretations of American and Civil War history.

Blum and Matsui outline three goals for the book: first, “to place the devil and forces of evil on equal footing with God and the forces of good in American religious history;” second, to emphasize the importance of “extrabiblical sources” in understanding how Americans connected Christianity to their everyday lives; and third, to demonstrate that religion is critical to understanding the Civil War. By “diving into the demonic” the authors find that some religious concepts were “central, even pivotal, to how Americans understood, experienced, and created the war.” Their goals are well met, and their argument is convincing.

The book is organized into six chapters. The first addresses how the biblical story of Satan’s fall was grafted onto the issues of slavery and southern secession. Preachers like G.W. Henry used contemporary American politics to “reconceptualize” Christian history: Satan was the “first secessionist” who, enraged by the angel Michael and his “abolitionist friends” and their love of freedom, attempted to make “poor slaves” of humanity. According to Henry, the “secessionist, Lucifer” bore a striking resemblance to his “southern children.”

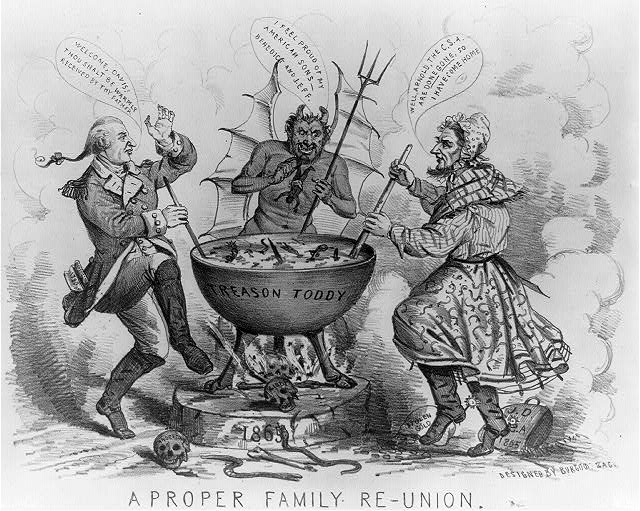

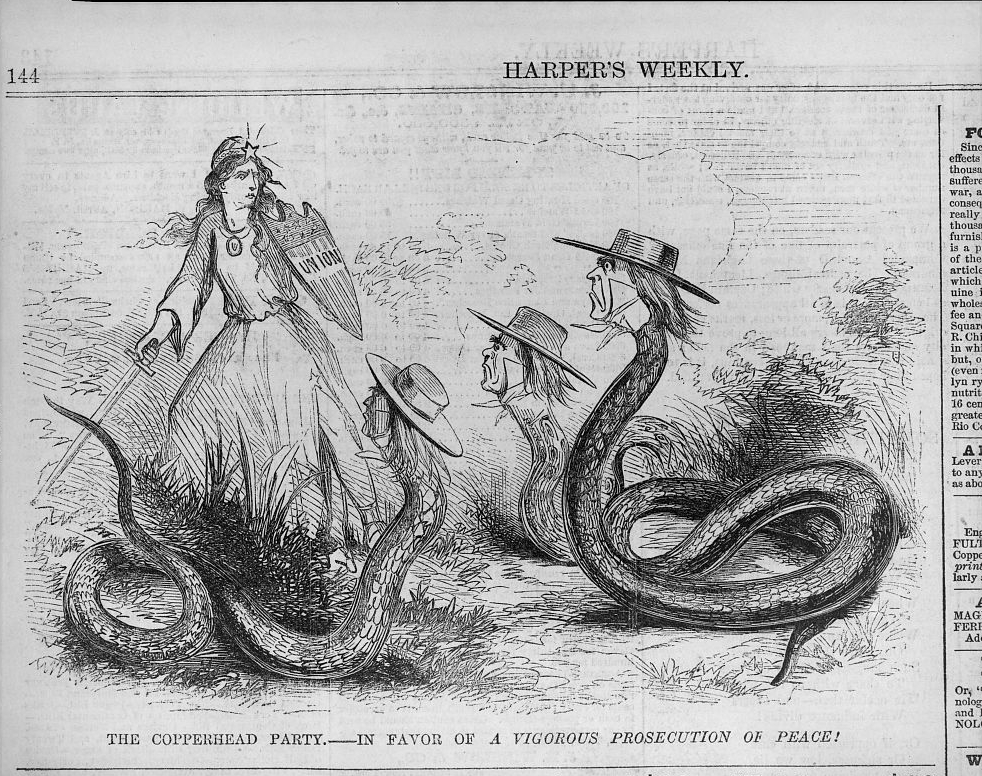

Other Unionists followed in a similar vein portraying the Confederates and their cause as one of “disunion,” influenced and directed by the devil, while African Americans likened enslavement to hell. By using this language, opponents of slavery and secession rendered the two as beyond politics; the embrace of both led to a life of eternal damnation.

The second chapter deals with the wartime experiences of individual combatants. When confronted with the visceral nature of warfare soldiers often articulated their experiences using religious language, specifically engaging with the notion of evil.

It is here that the authors expand on idea of war as being “all hell” by detailing the process by which soldiers on both sides demonized each other and how men used the language of “radical evil” to describe the conditions they suffered under. Likewise, those battling illness in military hospitals found life to be “a desolation” and captured soldiers described prison camps as “hellish” and “infernal.”

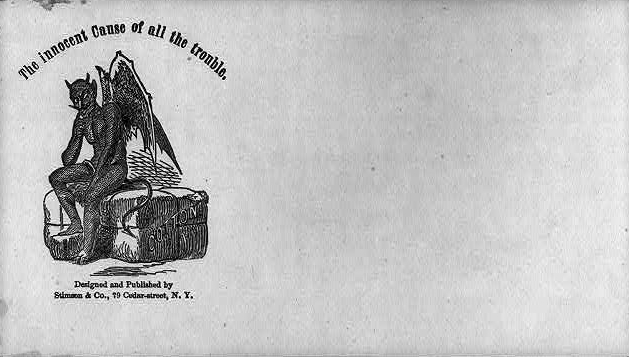

The third chapter examines Emancipation to see how Americans comprehended slavery’s end. Blum and Matsui find that Americans’ use of graphic imagery to create and capture the war brought its hell into the mainstream by moving Satan and evil from the sphere of common folklore to that of commercial consumption.

In the last three chapters, the authors examine what they see as a shift in the attitude of Americans after emancipation from condemning the devil’s works to embracing them and positively transforming the environment of the war into hell.

The fourth chapter picks up from the second and looks at how “fighting like demons” became a positive affirmation of military prowess. Soldiers engaged in increasingly “demonic” behavior during the later stages of conflict as exemplified through atrocities such as the massacre at Fort Pillow.

This dynamic presented a particular motivation for Black soldiers to “fight devilry with devilry” as they recognized that if they lost in battle their lives would be forfeited. Chapter five deals with how Americans used concepts of evil and illegality to address the actions of the guerillas during the war while chapter six looks at the actions of the Ku Klux Klan and how its members “personified and performed the demonic” as they engaged in terrorism to challenge Reconstruction.

The examination of “extrabiblical sources” is critical to the authors’ argument, and they consult a wide range of them throughout the book. They find that Americans tended to draw on historical resources from European popular culture to shape their ideas about the conflict. John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Dante Alighieri’s The Inferno, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and Shakespeare’s plays are constantly used as reference points in pamphlets, letters, and speeches. Blum and Matsui also use official documents and histories and examine the period’s print culture.

The biggest strength of the work is its examination of visual art. Through vivid descriptions of statues, pamphlets, photographs, and the images found on paper and envelopes the authors show just how much the war brought images and ideas of evil into the forefront of American culture and demonstrate the explicitly religious nature of these ideas. This analysis gives the reader a real sense of how Civil War era Americans interpreted and interacted with these objects.

One of the most interesting examples of this is the snake. From an animal that represented unity, resistance, and liberty, over the course of the war Americans came to see the snake as a symbol of the presence of evil and disunity in political and military affairs.

The biggest disappointment of the book is its distracting lack of images. This is particularly true for the third chapter, which focuses almost entirely on examining the visual culture of the period, including how the conflict offered “new spaces of meaning” for photography. This a frustrating omission in what is otherwise a fascinating work.