There is no greater insult today in American politics than to call someone an "elite." No one has hurled that insult more than Donald Trump. Americans have long been suspicious of “elites” but, as historian Steven Conn describes this month, just who they are has changed a lot over the last 200 years.

Let’s start with a poll: Which person described below would you call an “elite”?

A) The multimillionaire real estate tycoon who inherited his business from his multimillionaire father.

B) The mixed-race public-interest lawyer raised by a single mother.

The answer you chose may say a great deal about your political point of view and the cultural assumptions that undergird them.

President Barack Obama in 2012.

Choice A describes President Donald Trump, who built his campaign on angry denunciations of “elites.” Choice B, of course, is a thumbnail sketch of one of the primary targets of Trump’s rage: President Barack Obama.

2016 might well be called the Year of the Populists around the world. From the Philippines to Poland, from Brexit to Trumpismo, politics across the globe were upended by voters angry at … well, any number of things. Lumping them together, the commentariat called all these angry voters “populists” and it has expended a good deal of energy defining the species.

President Rodrigo R. Duterte of the Philippines posing with a military division in 2016 (top left). A 2015 demonstration in Gdansk, Poland against the populist ruling Law and Justice Party (top right). A sign supporting Britain leaving the European Union (bottom left). A 2016 London rally in favor of remaining in the European Union (bottom right).

Whatever else they may or may not have in common ideologically, these populists share an antipathy toward “elites.” But we haven’t spent nearly as much time defining just who those people are, what they’ve done to deserve the wrath of voters, and what the implications might be when voters turn on them.

Americans have a funny relationship with elites.

We worship our “elite athletes.” We swoon patriotically over our “elite military units” like the Green Berets and SEAL teams. We seek out “elite” doctors when things go wrong with our health.

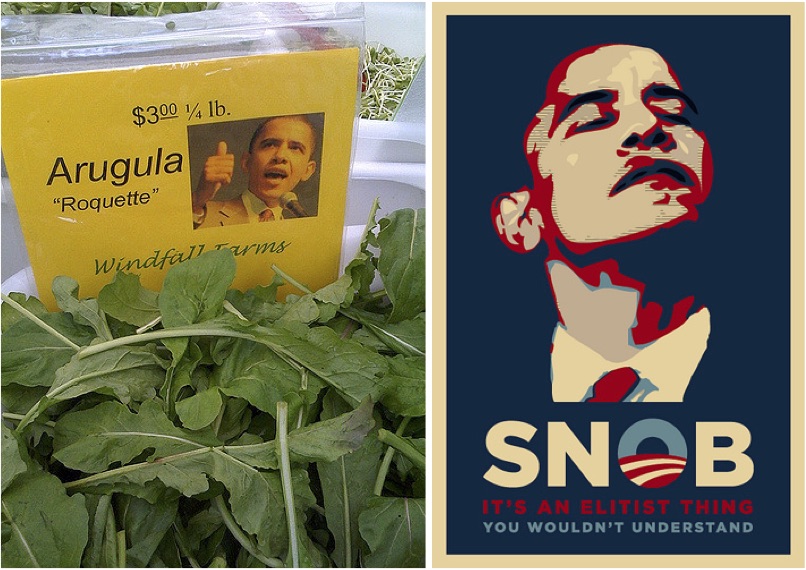

Obama’s preference for arugula lettuce became a means for opponents to paint him as an elitist (left). A variation on Obama’s “Hope” campaign poster, this parody presents the president as a snob and elitist (right).

But “elite” has become an epithet lately in our political discourse. The elites are, ipso facto, the enemy of the “people.” They are responsible for what has gone wrong, what is going wrong, and what threatens to go wrong in the future.

But who are “they,” more precisely, this cabal of elites who run the show, game the system, and subvert our democracy in the process? Part whipping-boy, part straw-man, the elite serve a rhetorical purpose for sure, but tracing just who has been on the receiving end of the epithet tells us interesting things about how American politics have changed over the decades.

When Elites Were Revolutionary

The declaration made in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776 formally announced what would become not only the American Revolution but the Age of Revolution. In France in 1789; in Haiti in the 1790s; across Europe in 1848; culminating perhaps in Russia in 1917.

Among the features setting the American Revolution apart from those that followed, however, is that it was in many ways a revolt of the “better classes,” or the elite. While the loyalties of ordinary colonists were deeply divided, those who led the movement to divorce from Great Britain were among the wealthiest, best educated, and, especially in Virginia, landed, slave-owning men in the colonies.

A depiction of the drafting committee presenting its work to the Continental Congress in 1776 (left). President George Washington leading troops against a populist uprising known as the Whiskey Rebellion in 1795 (right).

Many of them, in fact, were deeply suspicious of “the people”—whom they referred to derisively as “the mob.” When these elite met in Philadelphia to draft the Constitution, they baked that suspicion into our political system.

Unwilling to have the people elect the chief executive, they created the truly bizarre Electoral College. Uncomfortable that the legislature should correspond to the population, they invented the Senate to counter-balance the House of Representatives in giving states—really just a set of arbitrary lines on the map—equal power.

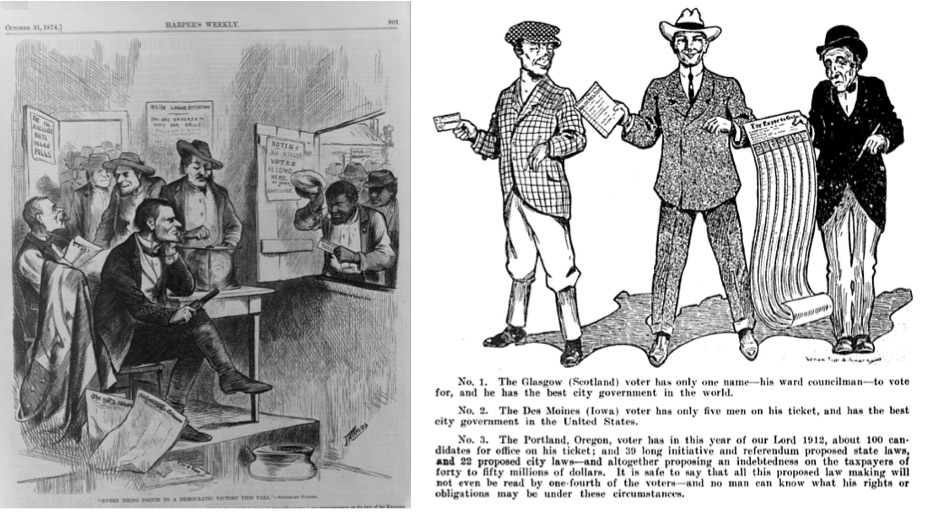

And states themselves echoed these suspicions of “the mob” by restricting the right to vote in all sorts of ways. Most infamously, Southern states made it effectively impossible for African Americans to vote between the 1870s and the 1960s. In the last several years, states controlled by Republicans, like Indiana and Wisconsin, have enacted voter restriction laws that have curtailed access to the polls dramatically.

A Harper’s Weekly cartoon depicting African Americans being denied the right to vote in 1874 by the White League (left). A 1912 cartoon mocking Oregon’s election system in which voters weighed in on a variety of proposed state and local laws (right).

In short, the United States was created and shaped by people who were not comfortable with democracy.

In a letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, George Washington wrote: “It is one of the evils of democratic governments, that the people, not always seeing and frequently misled, must often feel before they can act.”

And he was not alone in his disdain for “the people.” Alexander Hamilton would have been pleased about the sky-high ticket prices now serving to keep the riff-raff out of his namesake Broadway hit.

At the same time, plenty of observers in the early years of the republic noted that distinct lack of deference ordinary Americans showed their betters. Alexis de Tocqueville noted that American men all greeted each other with handshakes and thus ostensibly as equals. No one bowed before their betters in the United States, and if a rich man walking through town should meet “his cobbler on the way, they stop and converse; the two citizens discuss the affairs of the state and shake hands before they part.”

Across the first decades of the nation’s history, citizenship rights—particularly the right to vote—caught up with this cultural sense of equality. By the election of 1860, almost all white men could vote. Four million enslaved Africans certainly could not; nor could women of any color. (Americans would remain scared of “mob rule” by women, of course, until 1920.)

Men looking at the window display of the National Anti-Suffrage Association in Washington, D.C. in 1911 (left). A sign outside a New Hampshire polling place in 2013 warning of the photo ID requirements to vote (right). Since 2006, 33 U.S. states have enacted voter identification requirements.

And in 1860, those white American men elected as president a man whose personal story aligned with the nation’s egalitarian, anti-elite aspirations: Abraham Lincoln. Or at least that’s what we want to believe in retrospect. Lincoln took office having received less than 40% of the popular vote—the other three major candidates that year split the remaining 60%.

Lincoln embodied what Americans wanted to believe about their political system. Wise without a formal education, from humble beginnings without having been in any squalid sense poor, Lincoln represented the promise of what an ordinary American could be. He remains the most biographized American figure, supplanting that other figure who had much the same cultural resonance, Benjamin Franklin. Lincoln, much like Franklin, demonstrated that one could rise to the top without being an “elite.”

Robber Barons, Fat Cats, and the New Moneyed Elite

The Civil War, among many other consequences, accelerated the growth of large-scale industrial capitalism, especially in the burgeoning cities of the North and the Midwest. The size and scale of the fortunes generated by the unfettered, unregulated, and untaxed industrial economy simply boggled the minds of observers and seemed to put the lie to the notion that Americans lived in a nation of equals.

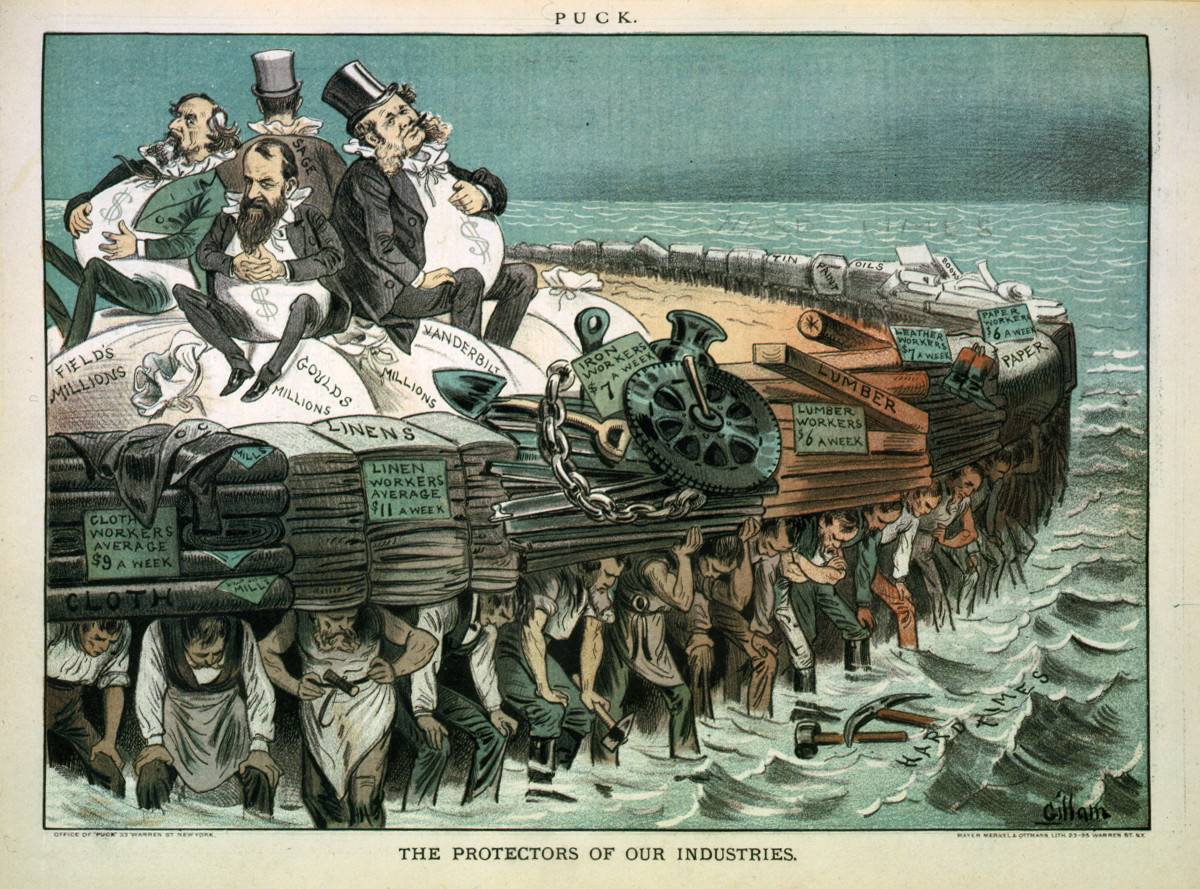

For every robber baron who emerged in the late 19th century, a thousand “wage slaves” were created. Here was America’s new elite. They remain familiar to us—Rockefeller, Carnegie, Morgan, Mellon, Field, and the rest—their names literally carved in the stone of the buildings dedicated to them.

In the 1830s, de Tocqueville noted that the rich wanted to "conceal" their wealth from public view. "His dress is plain," the Frenchman commented, "his demeanor unassuming."

By the end of the century, America’s rich had changed their attitude. No more unassuming demeanors, but ostentatious flaunting instead. In 1899, the sociologist Thorstein Veblen developed a theory of this new leisure class who participated in a whole set of behaviors he labeled “conspicuous consumption.”

Many Americans objected to the rise of this new moneyed elite for a number of reasons, but none more than the influence these plutocrats had over the political system.

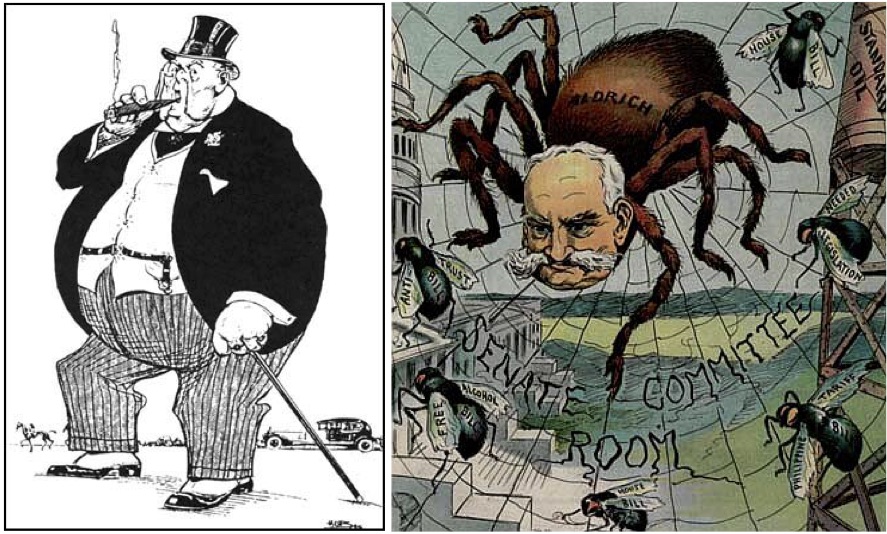

A 1925 cartoon of a “fat cat” (left). A 1906 cartoon depicting Senator Nelson Aldrich as a spider devouring proposed legislation, such as anti-trust regulations (right).

The term “fat cat” itself dates to the 1920s and did not simply mean wealthy person. The term, as coined by Frank Kent in the pages of H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury, described a very rich person who wanted to buy political influence, a robber baron who, “finding no further thrill . . . of satisfaction in the mere piling up of more millions, develops a yearning for some sort of public honor and is willing to pay for it.”

In fact, the new moneyed class had been corrupting politics for at least a generation. In 1906 journalist David Graham Phillips published a series of articles investigating the way money sloshed around in the U.S. Senate. He gathered them together as a book with the title The Treason of the Senate.

But for their part, many of the rich elite seemed to revel in the influence their money could buy. In 1895, millionaire businessman Mark Hanna quipped, “There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money and I can’t remember what the second one is.” The following year he financed William McKinley’s successful bid for the White House and won a Senate seat in Ohio to boot.

Enter Economic Populists

The election of 1896 was the culmination of the first wave of populist unrest in the United States and the first political reaction against the new moneyed elite.

The original populist movement grew out of the increasingly dry and unprofitable soil of America’s grain belt. Farmers through the 1870s and 1880s in the nation’s rapidly expanding midsection found themselves squeezed economically by a number of forces including railroad shipping rates, access to bank credit, falling farm prices on national and international markets, and drought in the semi-arid regions of the Great Plains.

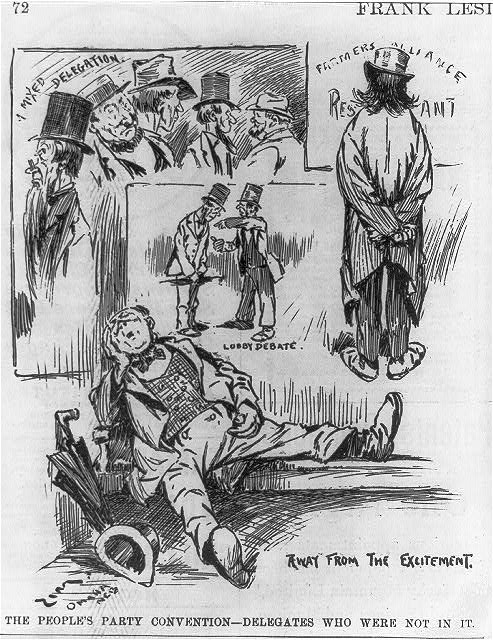

They decided that the root of their problems lay with wealthy merchants, bankers, and industrialists and that the solution to those problems was electoral politics. In 1892, they gathered in Omaha, Nebraska and formed the People’s Party.

In the “Omaha Platform” they issued on July 4, the populists minced no words in describing their political anger.

They denounced land ownership “concentrating in the hands of capitalists.” And they decried that, “The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of those, in turn, despise the republic and endanger liberty. From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes—tramps and millionaires.”

Later in the document the populists declared: “Wealth belongs to him who creates it, and every dollar taken from industry without an equivalent is robbery.”

If these middle Western farmers in 1892 sound to you a bit like, well, European Marxists, you can be forgiven. Their proposals were quite radical—nationalizing the railroads, for example. But they actually looked backward and wanted to give the country back to “the plain people” from whom it had been taken by the capitalists, and in 1892 that message did quite well at the polls.

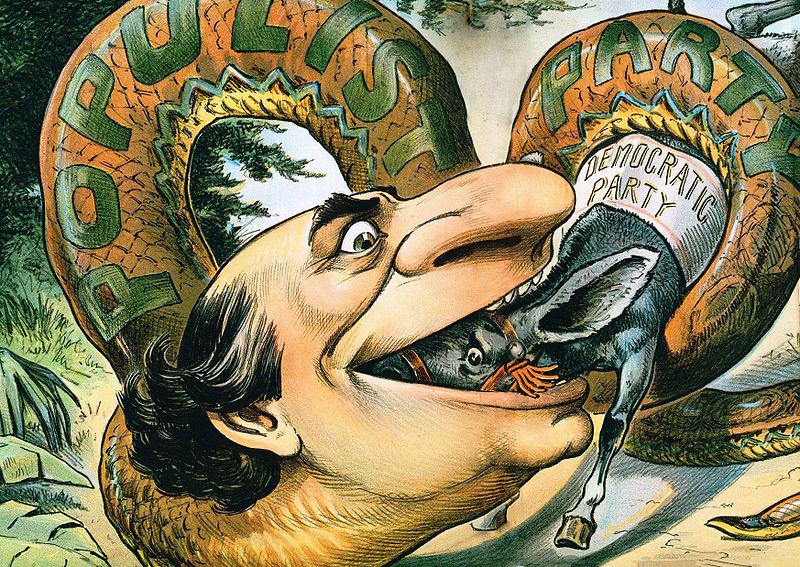

While the movement flamed out after the election of 1896, it left its mark on the language of American politics. The elites, who perverted the political system to their own advantage, were the rich.

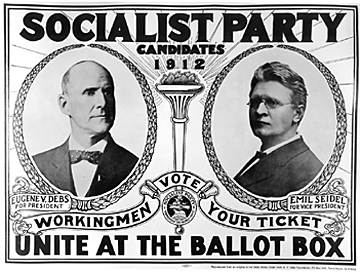

That refrain in American political discourse continued through the early decades of the 20th century. Socialism, with its analysis of class conflict, was a respectable political position, at least before the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs won a million votes in his run for president in 1912; he got nearly that many in 1920 when he ran while sitting in prison for speaking out against American involvement in World War I.

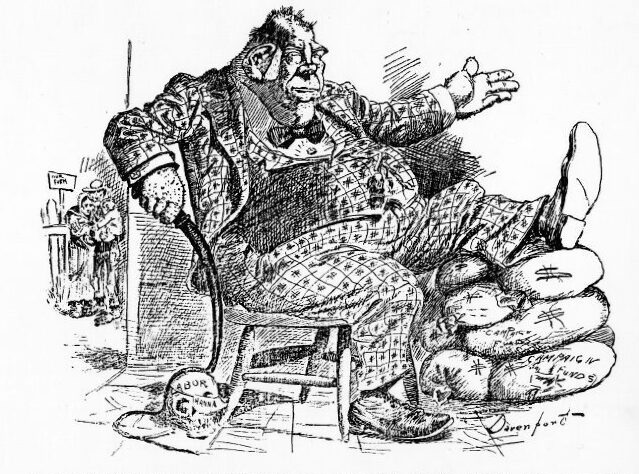

The language of class conflict—that there were two kinds of Americans, “tramps and millionaires,” and that the latter was exploiting the former—reached a crescendo in the 1930s during the Great Depression.

The Depression seemed to prove all the predictions of socialists right: the capitalist economy had collapsed on itself, leaving ordinary Americans in desperate straits. The Depression was the fault of the elites who ran the economy and had betrayed the people who worked for them.

Franklin Roosevelt did not need to take advantage of those feelings in his 1932 campaign; simply running against the flailing Herbert Hoover was enough to ensure his victory. But in 1936 he did. In accepting the Democratic nomination to run for a second term, Roosevelt delivered a blistering attack on the moneyed elite. He called them “economic royalists,” harkening back to the nation’s founding struggle against monarchy, and he sneered at the “privileged princes of these new economic dynasties.”

With its stark juxtaposition, this 1937 photo of African Americans in a relief line in front of a billboard presenting an idealized America became instantly iconic (left). Despite President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wealth and elite upbringing, many thought of him as a man of the people (right).

At the end of that campaign, Roosevelt denounced those princes again. Railing against “business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking,” he told the crowd in Madison Square Garden, “We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as government by organized mob.”

Then FDR went on: “Never before in all our history have all these forces been united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.” The crowd roared

Never before—and never since—has a presidential candidate appealed so directly to voters by pitting ordinary Americans against the moneyed elite. And when he won 60.8% of the popular vote in 1936, and all but two states, never before had a candidate won so sweepingly.

Enter the Experts

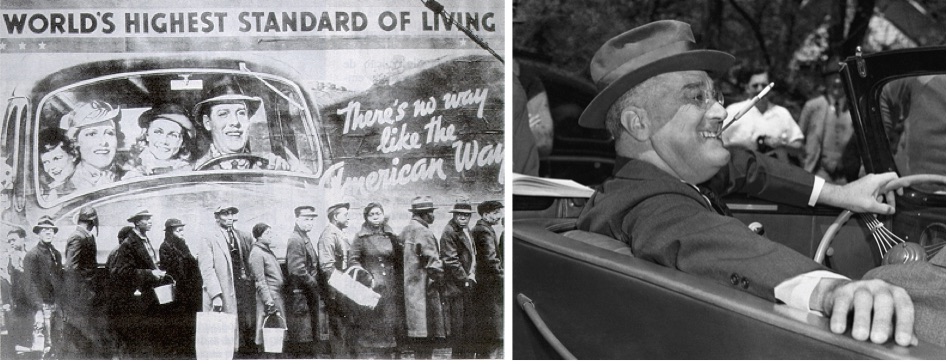

Even as Roosevelt was campaigning against the economic elites and rallying supporters with the rhetoric of class conflict, he was introducing a new kind of elite into national government: the highly specialized, often academically connected expert. Roosevelt’s New Deal was both shaped and run by these people—economists, lawyers, agronomists, scientists, and the like. Together they became known as FDR’s “Brains Trust.”

This wasn’t the first time experts participated in government. At the turn of the 20th century, many of the reforms associated with the Progressive Era were the products of intellectual expertise. They filled a need that seemed both obvious and urgent.

As American life became altogether more complex, complicated, and beyond the control of 19th century political and social structures, growing numbers of people came to believe that only scientific rationality could tame the forces of industrial capitalism and the problems it caused.

That view of American society was given its fullest expression in 1914 by journalist Walter Lippmann in his book Drift and Mastery. “We are all of us immigrants in the industrial world,” Lippmann wrote, “and we have no authority to lean upon.” Science and expertise promised “mastery” of this brave new world; without it, America was doomed to drift.

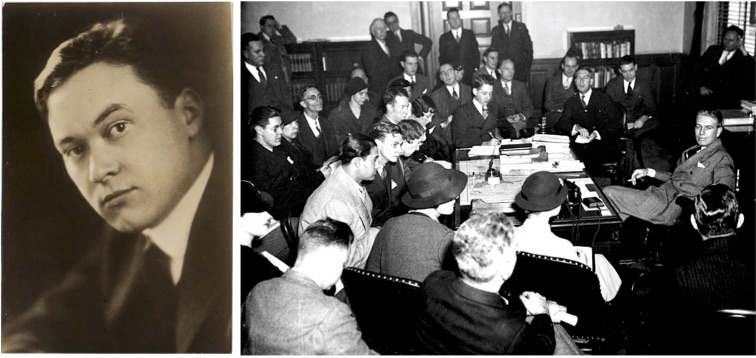

The journalist Walter Lippmann in 1914, the year he published Drift and Mastery in which he heralded the benefits of expertise (left). A member of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “brain trust,” Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Rexford Tugwell had been an economic professor at Columbia University. In this photo from the early 1930s, he was holding a press conference about a new act regulating food and drugs (right).

Progressive experts found themselves on the margins of political life during the 1920s, but after the economic collapse of the Great Depression, Roosevelt brought expertise back to Washington with a vengeance. As Depression turned to war and World War II slid into Cold War, experts and the new class of intellectual elites became a central part of the governing apparatus of the nation.

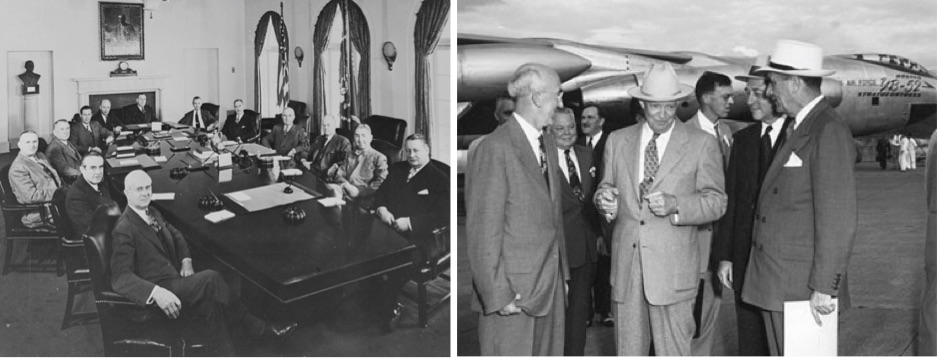

In 1946, Congress created the Council of Economic Advisers, and the following year it created the National Security Council. In 1951, Harry Truman established the Science Advisory Committee. After the launch and orbit of the Sputnik satellite and the ensuing panic over the state of American science, Dwight Eisenhower gave the Committee more heft by renaming it the President’s Science Advisory Committee in 1957.

President Harry S. Truman meeting with his cabinet in 1949 (left). President Dwight D. Eisenhower chatting with members of his cabinet while inspecting a prototype of a new plane in the early 1950s (right).

All three of these bodies share three things in common: first, they are housed within the executive branch of government and provide information and counsel to the president; second, they reflect the need in the postwar world for expertise about domestic matters and foreign and military policy; finally, they are composed (or are supposed to be composed) of experts, appointed rather than elected to their positions.

Like Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy graduated from Harvard. And like FDR, JFK brought to Washington a cadre of experts and academics (many of them, naturally, from Harvard) that collectively came to be known as “the best and the brightest”—men like Robert McNamara and McGeorge Bundy. “You can’t beat brains,” Kennedy was fond of saying and he wanted to be surrounded by them.

President John F. Kennedy conferring with National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy in 1962 (left). President Kennedy and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara meeting outside the Oval Office during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 (right). Both Bundy and McNamara had been Harvard Professors before joining the Kennedy administration.

This network of intellectual elites ran through government, foundations, universities, and think tanks. While members of this network might disagree with one another over policy choices, they created a remarkable continuity and consensus, at least for 20 years or so after the Second World War. So well established was this Establishment by 1956 that sociologist C. Wright Mill could call them “The Power Elite” in a book of the same title.

Many who belonged to this power elite came from old families and grew up cossetted with family money, but wealth was not what made them part of this elite. Rather, membership came from a combination of intellect and public service. McNamara, for example, was the son of a man who worked for a wholesale shoe company in San Francisco.

They went to the same small set of schools—Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and a few others—and many distinguished themselves during World War II. After the war, they set about running the country.

The Revolt against the Elites

During the 1952 presidential campaign, a supporter of Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson called out to him at a campaign event: “Governor Stevenson! All thinking people are for you!” To which Stevenson replied, “That’s not enough. I need a majority.”

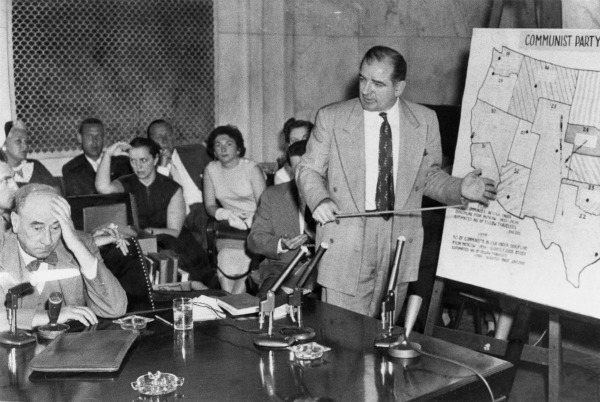

Even as they settled into power during the Cold War, this intellectual elite found itself under attack, first from the political right. Senator Joseph McCarthy, in his shambolic and vicious crusade against communists, directed a great deal of his bile at East-coast, Ivy-League-educated members of the State Department.

McCarthy wasn’t merely grinding a personal ax, however. Plenty of conservatives during the era harbored suspicions about “eggheads” who included, as the right-wing magazine The Freeman complained in 1951, “Harvard professors, twisted-thinking intellectuals … in the State Department burdened with Phi Beta Kappa keys and academic honors.”

In the now-infamous speech in Wheeling, West Virginia that launched his career, McCarthy announced that the nation was infested with communists and blamed “the bright young men” with “the finest college education” for the disease.

McCarthy never did find any communists lurking at the State Department or anywhere else. But his attacks on those over-educated, “over-emotional,” “feminine,” and “self-conscious prigs,” as right-winger Louis Bromfield described the “egghead,” did get a number of State Department employees fired. When they departed, they took considerable expertise with them, especially about the communist world. It left American diplomacy badly positioned during the crucial period that followed.

Gone, however, was the equation of “elite” with wealth and privilege. For McCarthy, a Princeton or Columbia education was far more threatening to the health of the Republic than inherited fortunes or control over huge corporations.

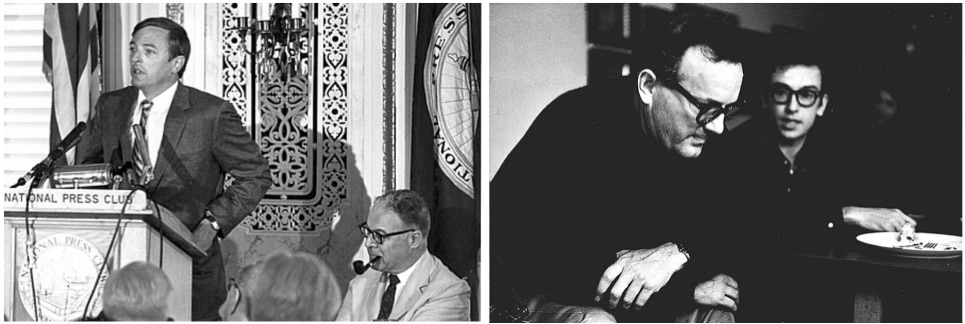

In 1963, William Buckley, a harpsichord-playing, European-educated son of wealth with a reptilian smile and a love of his own erudition, demonstrated that he was no elite when he quipped, “I am obliged to confess I should sooner live in a society governed by the first two thousand names in the Boston phone directory than in a society governed by the two thousand faculty members of Harvard University.” Of course Buckley went to Yale, so perhaps this was more about old school rivalries than about Buckley’s man-of-the-people bona fides.

William F. Buckley Jr. addressing the National Press Club in 1965 as the Conservative Party’s mayoral candidate for New York City (left). Sociologist C. Wright Mills with journalist Saul Landau, date unknown (right).

C. Wright Mills, however, was hardly a man of the right. In fact, he coined the term and became an inspiration to the “New Left” of the 1960s. He too saw much to dislike about the new power elite, though for different reasons.

If those on the right objected to intellectuals for broadly cultural reasons—educational pedigree, coastal addresses, cosmopolitan tastes—Mills saw the power elite as fundamentally anti-democratic. They framed the choices, set the terms of the debate, and often made the decisions that shaped the lives of people not only in the United States but around the world as well. No one had elected them to do all that.

This is where the young people of the New Left started to grow disenchanted with the Establishment.

By the late 1960s, the Vietnam War corroded faith in the elite entirely. Not only was the war a military and moral failure, but Americans had been repeatedly lied to about it—and regularly by members of the power elite.

That all became crystal clear in 1971 with the release of the Pentagon Papers. The following year, journalist David Halberstam published a study of the early years of American involvement in Vietnam, examining how the decisions made in the Kennedy White House led inevitably and inexorably to tragedy and disaster. He titled it with no small sense of irony: The Best and the Brightest.

President John F. Kennedy with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell D. Taylor and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara discussing a possible coup in Vietnam in 1963 (top left). McNamara lecturing on Vietnam during a 1965 press conference (top right). South Vietnamese women welcoming McNamara to Saigon in 1964 (bottom left). Opponents of the Vietnam War demonstrating against McNamara in 1967 (bottom right).

By the 1970s, for those on one side of the political spectrum, Vietnam poisoned their trust in the intellectual elite. Experts were really amoral technocrats; science was responsible for atomic weapons and napalm and it too was fundamentally inhumane.

For those on the other side of the political spectrum, the McCarthyite connection between intellectuals and communists meant that the former could never be trusted. And by the end of the 1960s, college campuses had become bastions of long-haired, dope-smoking anti-Americanism.

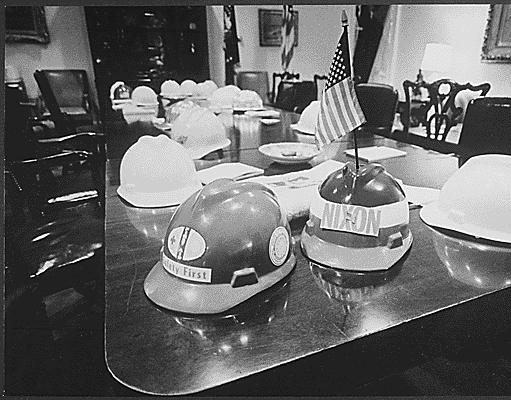

May 8, 1970 provides a symbolic moment of sorts marking the shift in our attitudes about elites. On that day about 1,000 college (and high school) students gathered in Lower Manhattan to protest the American invasion of Cambodia and the killing of four students at Kent State University in Ohio. They were attacked by construction workers in what became known as “the hard hat riot,” and more than 70 people were injured.

In the 1930s, “hard hats”—blue-collar union members—had marched in the streets against factory owners and bankers and found a champion in Franklin Roosevelt. By 1970s, they were beating up students while Richard Nixon smiled in the White House.

The Paradox of American Anti-Intellectualism

“Everyone is entitled to his own opinions,” the politician and policymaker Daniel Patrick Moynihan liked to say in the 1960s, “but not to his own facts.” The line seems so antique now in our “post-truth” age, when people in positions of authority can proffer “alternative facts” with a straight face.

In fact, the right-wing attack on intellectual elites—and on the campuses where they reside and the expertise they generate—began in earnest during the 1980s.

Ronald Reagan regularly offered his own alternative facts when they suited his world view, like the “fact” that trees cause air pollution. He summarized his own college education by saying, “Going to college offered me the chance to play football for four more years.”

By the early 21st century, conservatives dismissed all sorts of things they did not like as conspiracies of intellectual elites, even in the face of settled science. Creationism came roaring back in the 1980s and religious fundamentalists insisted that it be taught in high school biology classes. George W. Bush agreed with them. The climate is changing too, but only if you listen to the egg-headed scientific elites.

President Ronald Reagan meeting with Vice President George H.W. Bush in 1984 (left). Governor Bobby Jindal speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2013 (right).

In 2013, Bobby Jindal, Republican governor of Louisiana, pleaded with his fellow Republicans to “stop being the party of stupid” and begged them to “stop insulting the intelligence of voters.” Four years later that plea sounds just as quaint and distant as Moynihan’s quote.

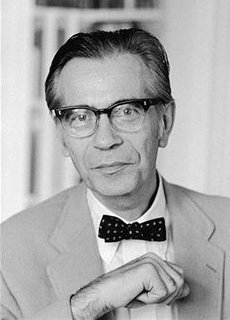

There is a long anti-intellectual tradition in American life. In 1963, the great historian Richard Hofstadter wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning book about it.

The irony of that tradition is this: never has a nation put so much faith in the power of education to achieve its aspirations of equality, prosperity, and freedom. Thomas Jefferson knew that the very Republic depended on it. “An educated citizenry is as vital for our survival,” he wrote, “as a free people.”

|

| Public intellectual and Columbia University professor, Richard Hofstadter published Anti-Intellectualism in American Life in 1963. |

States responded to this need by establishing free public school systems for their children. In 1863 the Federal government created the most democratically accessible system of higher education in the world when it sponsored the land-grant colleges.

It expanded that access even further after the Second World War when the GI Bill was passed. Education, Americans have always believed, can produce Jefferson’s “well-informed electorate” and put them on the path of upward mobility.

At the same time, there is no other country in the developed world so fundamentally hostile to experts, academics and other intellectual “elites.” Apparently, Americans want our children to be educated, provided they don’t actually learn anything. Four years of football after all and one wonders what Thomas Jefferson would make of the well-educated citizenry now.

At a moment when billionaires can successfully masquerade as “populists,” gone are the “economic royalists” from our political discourse. The real elites are journalists, researchers, and college professors. They now pose the greatest threat to the nation.

“Ignorance is strength,” George Orwell wrote in his dystopian novel 1984, and he wrote the book as a cautionary tale. Today’s populists, as they rage against the educated elite, seem to have adopted it as a how-to manual.

Read and Listen to Origins for more on U.S. politics: Media and Politics in the Age of Trump; Women Who Ran before Hillary; “Big Government” in American History; The American Two-Party System; “Class Warfare” in American Politics; American Populism; Presidential Elections in Times of Crisis; The 2016 Presidential Election; Women in American Politics; America's Post-Election Political Landscape; and America's Infrastructure Challenge

Dallek, Robert. Camelot’s Court: Inside the Kennedy White House. New York: Harper Perennial, 2013.

Fink, Leon. Progressive Intellectuals and the Perils of Democratic Commitment. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997.

Halberstam, David. The Best and the Brightest. New York: Random House, 1969.

Hofstadter, Richard. Anti-intellectualism in American Life. New York: Vintage Books, 1962.

Lasch, Christopher. The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995.

Mills, C. Wright. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956.

Oreskes, Naomi and Erik Conway. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010.

Tugwell, Rexford. The Brains Trust. New York: The Viking Press, 1968.