Greenland has been much in the news at the start of 2025. Donald Trump wants to buy the world's largest island for its natural resources and strategic position. In fact, as Matthew Birkhold writes, Greenland has been coveted for these reasons for hundreds of years, but now Greenlanders are demanding self-determination in new ways as they choose their path forward.

A good starting point for those seeking to better understand Greenland is Niviaq Korneliussen’s kaleidoscopic novella, Last Night in Nuuk.

Through a stream-of-consciousness narrative that interweaves text messages, journal entries, and letters, the reader is shown the lives of five young adults navigating friends, family, and love in the capital of Greenland. The characters attend downtown parties, struggle with their sexuality, track “likes” and “comments” on Facebook, experience domestic abuse, and dream of other places.

Snowy mountains loom in the background of a landscape covered in frost and splashed in bright sun, but this story does not depict Greenland through the eyes of an exoticizing Western outsider.

First published in 2014 in both Greenlandic and Danish and translated into English in 2019, the novella reveals Greenland from the perspective of a young, queer Greenlandic author. She paints a picture of a sometimes boring, claustrophobic town that is simultaneously rooted in tradition and connected to the broader world.

Last Night in Nuuk makes clear that Greenland is not a frozen fantasy but a vibrant, growing, global place. It has long been, even if that is not how many people outside of Greenland want to imagine it. To see beyond fantasies about Greenland, one must look to its history and culture. Only then can we begin to understand the future of the world’s largest island.

Beginnings

Between 2500 and 2000 BCE, the first people made their way to Greenland from the North American continent, when sea ice formed a passage across the narrow strait at Qaanaaq in the northwest.

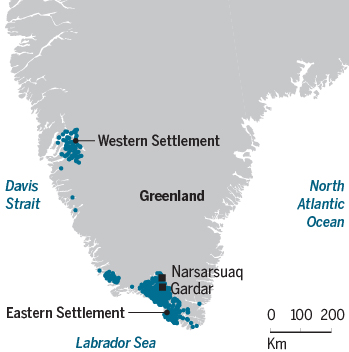

Over the years, Paleo-Eskimo peoples settled Greenland in several waves, including the Thule culture around 1300 CE, from which Greenland’s population today is largely descended. Amidst this Inuit migration, the Norse—led by Erik the Red—arrived and established settlements on the unoccupied southwestern part of the island around 985 CE.

The medieval Norse settlers relied on the ecological niches of Greenland’s fjords, building hundreds of farms to raise imported livestock and engage in limited agriculture. They hunted caribou, seals, and polar bears, and erected more than a dozen churches after Greenland converted to Christianity in the late tenth century.

At its peak, the population of Norse Greenland reached as many as 3,000 people and the island was heavily involved in European trade. They relied on iron tools, timber, and religious artifacts from Iceland and Norway and exported sealskins, whale products, and most importantly walrus ivory.

By 1100 CE, Greenland supplied much of Europe with ivory, a coveted luxury material used in reliquaries, crucifixes, game pieces, personal accessories, and regalia. Meanwhile, the Roman Church began sending bishops, starting with Arnaldur in 1124 CE.

The two settlements—Eastern and Western—became a tax-paying protectorate of Norway in 1261 CE. Following the personal union of Norway and Denmark in 1380, power shifted south to Copenhagen, though Bergen remained the primary commercial hub for exports. Greenland, rich in opportunities, was home to various peoples and connected to the globe through trade.

By 1350, however, Greenlandic walrus ivory faced competition from superior African and Asian elephant ivory, and demand faded. The Church stopped sending bishops. A cooling climate made farming difficult and filled the seas with ice, slowing and eventually ceasing shipping between Greenland and Norway.

The last extant record of Norse Greenland describes the wedding celebration of Thorstein Olafsson and Sigrid Björnsdóttir on September 16, 1408 CE. No one knows for sure how or why the settlements vanished around 1450 CE.

Nevertheless, stories of Greenland persisted in the European imagination. And Greenland—so named by Erik the Red to help entice settlers—continued to enchant those who thought of it.

Early Visions

Kalaallit Nunaat, or “Land of the Greenlanders” as the country is known in Greenlandic, has long attracted people because of its resources and Arctic location.

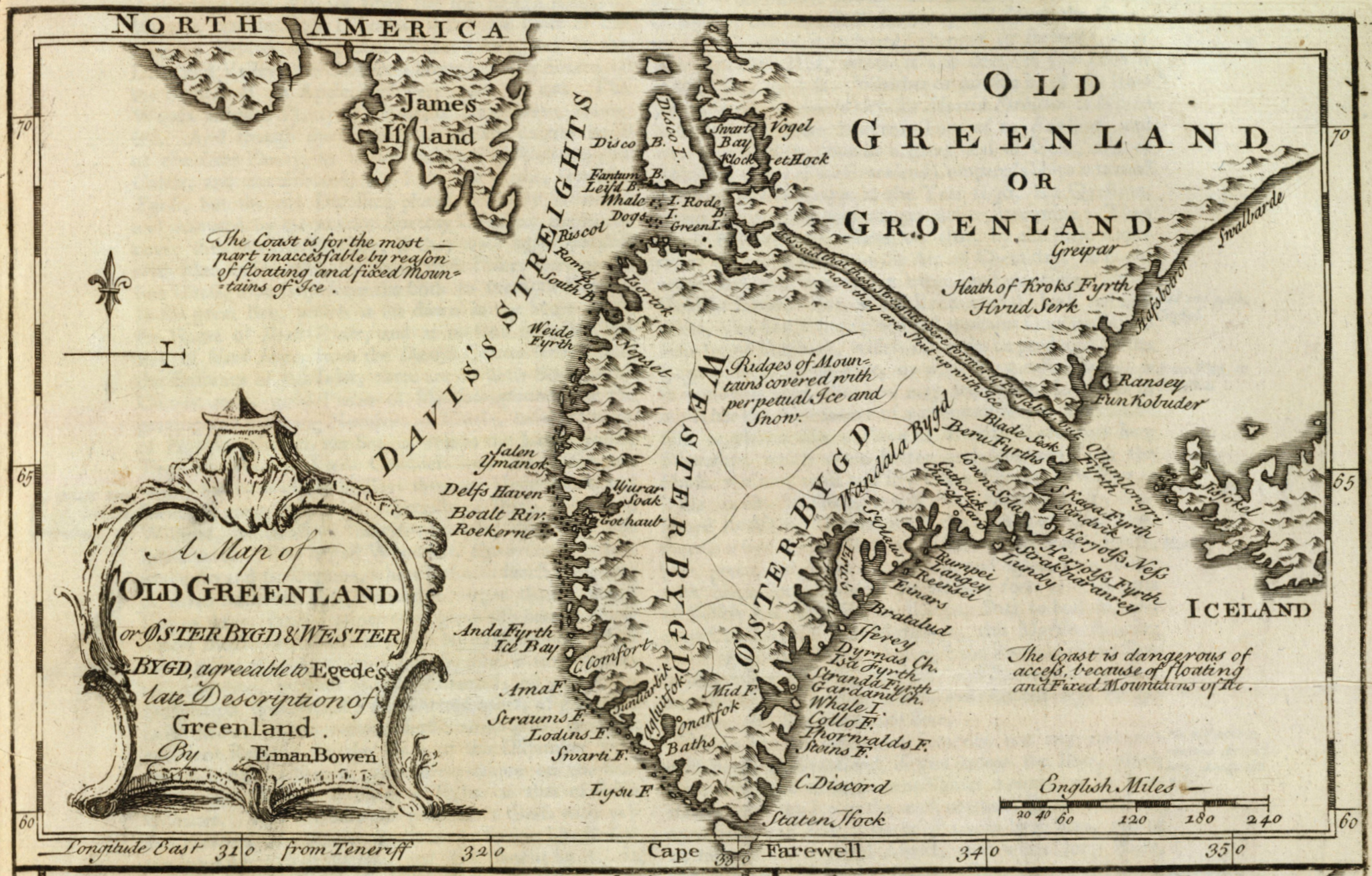

Greenland’s riches have dominated European discourse about the island since the Middle Ages, starting with a 14th-century report from the Norwegian clergyman Ívar Bárdarson to the Norwegian crown. Bárdarson documents the vast fishing and whaling opportunities in the fjords of the Eastern Settlement.

Like a game of telephone eventually played by writers who had never visited Greenland, reports through the centuries grew more exaggerated: Greenland was full of whale blubber, salmon, ivory, furs, falcons; it had verdant farms, was excellent for raising livestock, and was home to extensive deposits of silver and gold.

Casting the Inuit as murderous monsters was also a key element of these stories, which often took on a religious tone. “Christianity [was] rooted out by the savage Heathens,” concludes Hans Egede in A Description of Greenland from 1745. Once contact with the Norse settlers was lost, Greenland became a purely imaginative place for Europeans to project their fantasies.

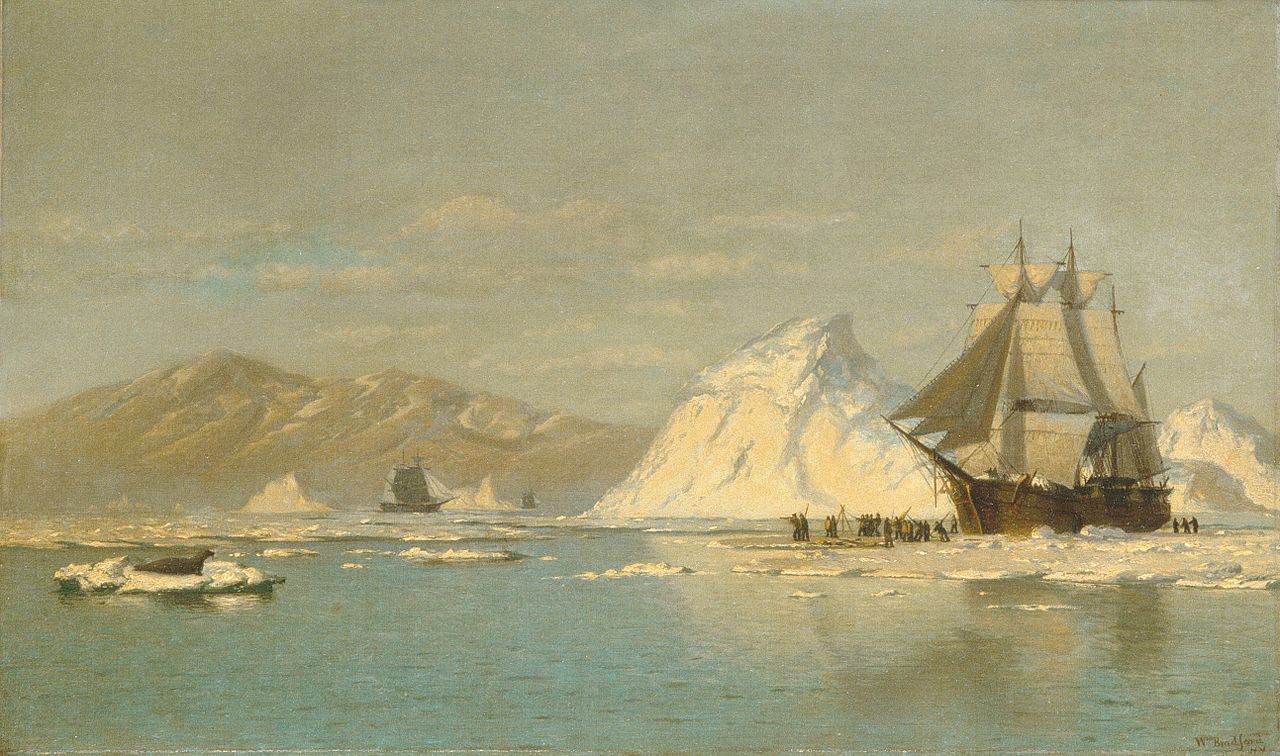

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, English, Scottish, Dutch, Hanseatic, and Danish sailors headed north in search of valuable whale oil for lamp fuel and soapmaking. Through flag-planting efforts, diplomatic missions, proclamations, rewriting maps, merchant muscle, and historical arguments, European rulers tried to claim the rich seas of the Arctic.

Copenhagen believed the early presence of the medieval Norse Greenlanders made a clear case for Danish sovereignty. In his Gronlandia from 1606, Arngrímur Jónsson put it simply: Greenland belonged to Denmark because it was “once governed by, and paid taxes to, Norway, and subsequently to Danish kings, when the Norwegian realm was ceded to Denmark.”

Now, Denmark was eager to reclaim Greenland. Religious zeal worked together with political and economic motivations. In 1536/37, Denmark-Norway had converted to Protestantism, and some religious leaders became concerned that the Norse settlers were still Catholic. For God and country, Denmark had to reestablish contact.

The missionary Hans Egede perhaps best exemplifies the chasm that often exists between reality and peoples’ imagination about Greenland.

In 1721, Egede arrived near present-day Nuuk to convert the lost Catholic Vikings to Lutheranism. When there were none, he established a mission, along with a trading station, to convert the Inuit instead. By 1774 the Danish crown created the Royal Danish Trading Company to run Greenland’s trade and administration.

For more than a century, Denmark tightly controlled the island, restricting Greenlanders from engaging in commerce with other nations, suppressing Indigenous cultural practices, forcing Inuit communities into settlement patterns to facilitate Danish trade, practicing wage discrimination, and excluding Greenlanders from political decision-making.

Most historical accounts of Greenland include a 300-year break between the end of the Norse settlements and the arrival of Hans Egede, ignoring the continuous presence of Indigenous peoples.

Unlike the Norse settlers, the Thule Inuit occupied fjord coastal zones that had fewer pastures but more abundant sea life. They were nomadic and developed hunting technologies that enabled them to make use of the marine resources, including light and large umiaqs that could deftly navigate ice-choked waters.

Apart from archaeological evidence, oral histories and Indigenous knowledge provide details about life in Greenland and offer a look into social taboos, relationships, and the environment, like the story of Kaassassuk, the Greenlandic variation of the pan-Inuit myth.

The stories also record interactions between the Thule Inuit and the Norse settlers. In several Inuit oral legends recorded in the 19th century, like the story about Uunngortoq, the Norse settlers overestimate their capabilities and misapprehend the environment around them. The oral tradition recalls a difference in lifestyles between the Inuit and the Norse and an implicit warning about the consequences.

The history of Greenland, told from an Inuit perspective, looks different than what we can reconstruct from Norse records.

As a circumpolar people, the Inuit are spread across Russia, the United States, Canada, and Greenland, a connective space comprising around 160,000 Inuit. From this viewpoint, the history of Greenland cannot be told separately from the history of the broader Arctic, whether Alaska or Chukotka.

The Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada is a good resource for those curious about this perspective. Listening to the Inuit tell this story is especially important because ignoring Indigenous voices has resulted in centuries of harms and misunderstandings.

Colonial Ordeals

Although Denmark established a trade monopoly with Greenland, nations around the world continued to eye Greenland for its resources. Scientists from Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States conducted research along the coasts and on the inland ice. And, increasingly, governments identified Greenland as a strategic location for military posts and shipping routes.

The American explorer and navy officer, Robert E. Peary, recognized in 1916 that Greenland “may be a valuable piece in our defensive armor. In the hands of hostile interests, it could be a serious menace.” He believed the island “might furnish an important North Atlantic naval and aeronautical base.”

Four years later, General William E. Mitchell testified to the Senate that he agreed with Peary and argued that establishing a presence in Greenland was more important than the Panama Canal. At the time, its population was approximately 14,000 people.

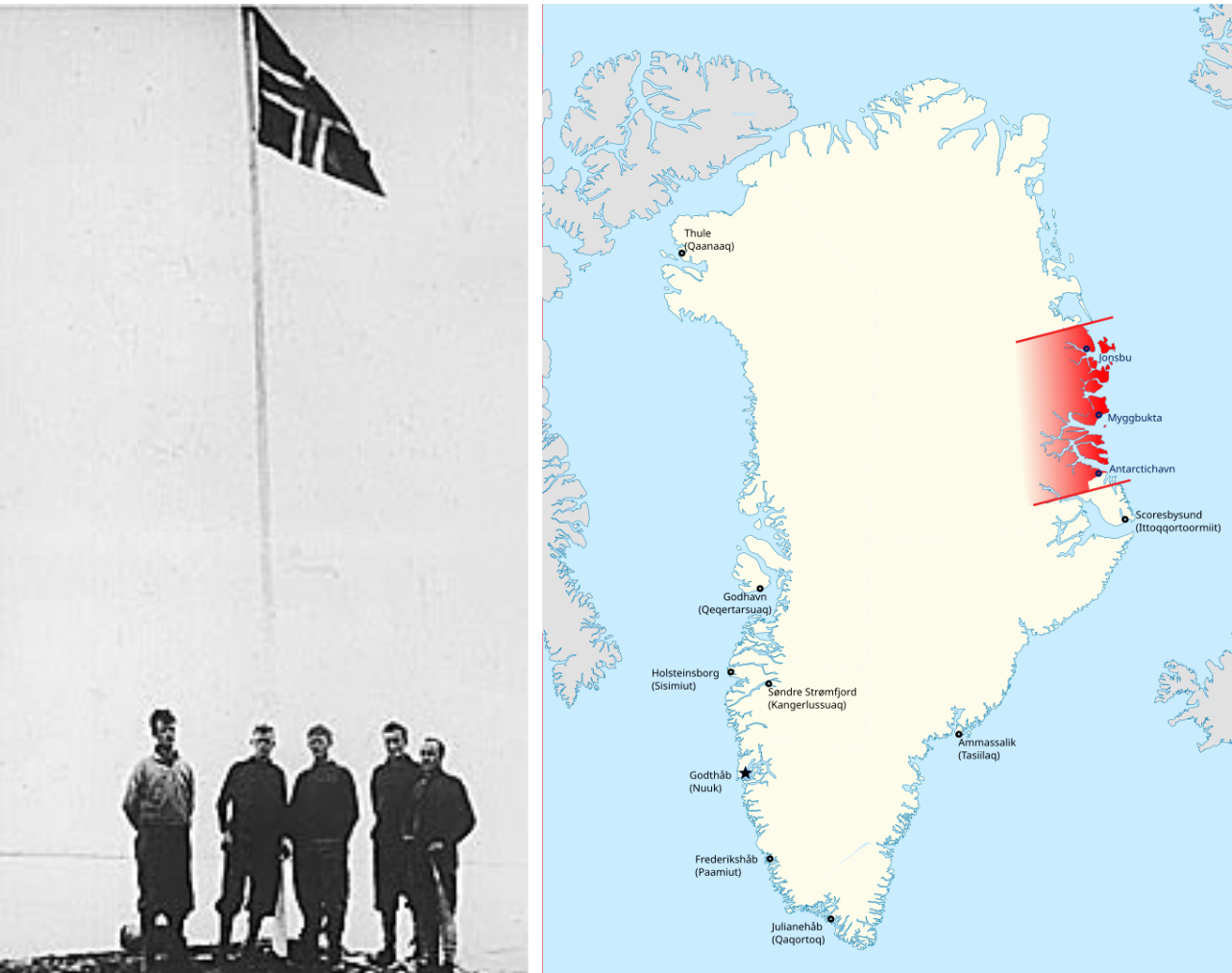

In 1921, Denmark formally declared all of Greenland—and not just its coastal trading posts—Danish territory. Nevertheless, Norway, separated from Denmark in 1814 and independent from Sweden since 1905, continued to establish hunting and scientific outposts.

Tensions reached a head in 1931, when Norway declared Eastern Greenland a Norwegian territory and dubbed it “Erik the Red’s Land.” The dispute went to the Permanent Court of International Justice, which decreed in 1933 that Denmark had sovereignty over all of Greenland, after which Copenhagen closed its colony off to much of the world.

During World War II, after Demark fell to Germany, the Danish ambassador to the United States, acting independently from Nazi-occupied Copenhagen, signed the 1941 Greenland Agreement, which permitted the U.S. to establish military bases and weather stations in Greenland while granting it de facto responsibility for its management and defense. Greenland was placed under U.S. protection without any formal alteration of its status as a Danish territory.

Among the sites protected by the United States was a vast cryolite mine that was crucial for the production of aluminum. American, Canadian, and Danish miners worked alongside Greenlanders to ensure the rare mineral stayed in Allied hands.

After the war, Greenland returned to direct control by Copenhagen, but American influences remained strong, including music, fashion, and even Sears, Roebuck and Company catalogs, which gave Greenlanders a chance to order modern appliances and gain another glimpse into an American lifestyle.

By treaty agreement, the U.S. military continued to operate bases in Greenland—and still does, for example, the Pituffik Space Base near Qaanaaq. In 1947, the Truman administration offered to purchase Greenland for the price of $100 million in gold. And in 1960 President Eisenhower again discussed the possibility with King Frederik IX of Denmark. Each time, Denmark vehemently refused.

Greenland was officially incorporated into the Danish realm as a county in 1953 and the colonial abuses that began with Egede continued now under the guise of modernization.

Greenlandic culture and language were suppressed. Greenlanders were subject to relocations, Inuit children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to Denmark, and women and girls were subject to reproductive violence. They faced systemic discrimination based on their ethnicity, had fewer legal rights, and were disenfranchised.

In the 1970s, Greenland’s independence movement flourished alongside efforts to preserve Greenlandic values and culture, culminating in the Home Rule Act of 1979. Greenland gained autonomy over its legislature and assumed responsibility for some domestic policies while Denmark retained control over foreign affairs, security, and natural resources.

A few years later, Greenland exited the European Economic Community due, in part, to its ban on seal skin products and fishing regulations. A new flag was adopted in 1985, and the University of Greenland was founded in 1987, offering higher education in Greenlandic. Greenland was beginning to secure new legal rights and the power to govern the country how its people wanted.

On June 21, 2009, Greenland achieved self-rule, gaining authority over judicial affairs, policing, and natural resources, while Greenlanders were recognized as a distinct people under international law.

In 2012, Greenlandic became the sole official language. Denmark retained control over defense and foreign policy and still contributes an annual block grant of 4.3 billion Danish kroner ($624 million), which covers nearly half of Greenland’s budget.

As Greenland becomes more economically self-sufficient, that amount will decrease, and the country—currently an “autonomous territory in the Kingdom of Denmark”—will gain full sovereignty. The path forward, most expect, will come through the exploitation of its natural resources.

A Changing Landscape

Greenland's shifting political landscape is just one of many changes taking place on the Arctic island, which is about one-quarter the size of the United States.

Nearly 80% of Greenland is covered by an ice sheet almost 1,800 miles long and 680 miles wide with an average thickness of one mile. For millions of years, the Greenland ice sheet has shed icebergs and meltwater in the summer and maintained its mass through accumulated snow in the winter.

Due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, however, the ice sheet is now losing ice at a rate unmatched in at least 12,000 years: an average of 30 million tons of ice every hour.

While this rapid melting spells doom for our planet, some see opportunity in the form of new access to minerals and other resources hidden under the ice, including rare earth minerals, uranium, graphite, coal, and precious stones. Speculators also believe there are large oil and gas reserves onshore and in the waters off Greenland.

Although some mines are operational, like the ruby mine near Qeqertarsuatsiaat, 80 miles south of Nuuk, many efforts are undermined by political, economic, and infrastructural challenges. Since no roads connect settlements in Greenland, transport must be done by plane, boat, snowmobile, or dogsled. Greenland’s Arctic location can also make on-site processing difficult.

Plus, the country maintains stringent environmental regulations. In 2021, Greenland’s left-wing environmentalist party, Inuit Ataqatigiit, even prevailed in the general elections by campaigning against the development of a rare earths mine.

Despite these hurdles, many companies and governments continue to pursue Greenlandic resources as an entry point to the Arctic. Scholars contend Chinese interest in Greenlandic zinc, for instance, is motivated by its foreign policy goals and not its mineral needs—part of its larger effort to establish what has been dubbed an “Ice Silk Road” to shorten the sea route from China to Europe.

For this reason and to shore up its own national security in an echo of General Mitchell, the United States actively lobbied Greenlandic businesses in 2025 not to sell mineral access rights to Chinese companies.

And a few years ago, a bid by a Chinese state-owned company to construct new airports in Greenland was opposed by American and European governments, which increasingly consider Greenland a focal point for future Arctic conflicts.

Luckily, many are ready to invest in Greenland.

In November 2024, a new airport co-financed by the Nordic Investment Bank opened in Nuuk. For the first time, the capital has a runway long enough to accommodate large jets, commencing a new era of tourism. In 2023, 76,477 tourists visited Greenland. Most are drawn to Ilulissat, where an additional international airport will open in 2026.

Situated 350 miles north of Nuuk, Ilulissat is home to a UNESCO world heritage icefjord, which produces thousands of icebergs each year. Here tourists can marvel at the icy wonders, go on dog sled rides, whale watch, hike, and enjoy Greenland’s breathtaking scenery. The national tourism board for Greenland sells the country as “a true winter wonderland.”

Greenlanders are well aware of these tropes and deploy them strategically. They know, too, that their natural resources are enticing to people around the world. After all, foreign excitement about Greenland is nothing new.

In Nuummioq, the first feature-length film produced entirely in Greenland from 2009, a side story involves the protagonist’s scheming cousin Michael, who has a plan to sell icebergs. “Here it’s like robbing a bank,” he says to Malik, “except it isn’t illegal.” The family laughs at Michael, who persists: “People will love it. We just have to sell it the right way. If we export it, it’ll be luxury goods. We’ll be rich.”

Michael has even dreamed up a commercial to sell his product: a rich guy in Bermuda drinking whiskey in need of ice cubes from icebergs. Everyone laughs. Selling icebergs is a punchline that is meant to show that Michael is a good-for-nothing, and that Westerners can be duped into treating abundant Greenlandic ice as a luxury product. They will fall for the fantasy of Greenland again and again. Now, however, Greenlanders are making sure that they are the ones who will benefit.

A New Chapter

Today, approximately 57,000 people live in Greenland. About 90% of the population identifies as Indigenous Inuit and a majority of the rest identify as Danish. Most speak both Greenlandic (Kalaallisut) and Danish, though students today learn English in school too. Almost a quarter of the population resides in Nuuk, yet cultural traditions related to hunting and fishing continue to play a significant role in Greenlandic life.

Fishing is the primary industry in Greenland, which exports a billion dollars of frozen fish and crustaceans annually, mostly to Denmark, China, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Germany. Apart from fish, whales, and seal products, most everything else is imported.

As a result, Greenland is well connected to the globe. Some Greenlanders fly to Iceland or Denmark when they get sick. They are influenced by Nordic architecture, watch American videos on YouTube, and buy party decorations made in China.

Greenlanders participate in the Arctic Winter Games, competing against Indigenous peoples from Sápmi, Yamal, Nunavut, and Alaska. Last year, a Greenlandic artist, Innuteq Storch, represented Denmark at the Venice Biennale.

Contemporary art in Greenland reflects this global reality.

Since 2013, for example, Ivinguak Stork Høegh has been producing a series of works that juxtapose images from Greenland with people, animals, and artifacts from the tropics to interrogate the concept of exoticism as it has been applied to the Arctic.

By incorporating collage elements from the 19th-century colonial archive, Høegh illuminates the role of art in the process of European exploration and exploitation. In her digital dreamscapes, the artist shows how peoples and places intersect in our ever-smaller, hybrid world: not in complete forms, but in constantly rearranging, splintered shards. Anymore, we do not know whether the iceberg or the flamingo is out of place. Space and time have been reconfigured, and Greenland may well be in the center.

This planetary mix-up includes America’s continued interest in Greenland.

In 2019, when Donald Trump made overtures about “buying” Greenland, he sought what earlier colonizing powers did before him: rich resources, an advantageous military position, and access to shipping routes that will only become more lucrative as the Arctic continues to open under pressure from climate change.

Greenlanders were offended, but there was an upside.

Trump actually “strengthened the Greenlanders’ bargaining position,” as Ebbe Volquardsen recently observed. “By presenting the 500-million-euro block grant that Denmark pays into Greenland’s budget each year as the market value of what countries are willing to pay for a military and commercial presence in Greenland,” Trump enabled Greenlanders to demand more autonomy.

This time around, right-wing American influencers have descended upon a more easily accessible Nuuk, and are engaged in various nefarious activities, including compelling kids with money and free lunches to participate in videos that make it seem like Greenlanders want to become American.

While some Greenlandic politicians have expressed an interest in forging new trade agreements with America, it is uncertain what the ultimate result will be. One thing is clear to Greenland’s Prime Minister Múte Egede, though: “[W]e don’t want to be Americans or Danes.”

Trump’s comments are nothing new; they are part of a broader history of colonial desires that mistake the fantasy of Greenland for reality.

Listening to Indigenous voices allows us to hear the truth. “Greenland is ours,” Egede recently expounded. “We are not for sale and will never be for sale.”

On June 21, 2020, the statue of Hans Egede that stands outside the Church of Our Savior on a rocky hill overlooking Nuuk was splashed with red paint. On the National Day of Greenland, protesters defaced the most potent symbol of colonial violence and wrote the words “decolonize” on its base.

Greenlanders are well on their way with the effort. In 2023, a government-appointed commission presented a draft constitution for a sovereign Greenland, and in 2024, the parliament announced a formal exploration of the process for a referendum on independence.

Despite what some foreign politicians fail to comprehend, calls for decolonization are not empty rhetoric. This is not a trendy phase that will pass. Whatever Greenland’s next chapter looks like, it will not start with an American yoke. Look no further than literature to understand the future that has long been desired.

In 1914, the Greenlandic priest Mathias Storch published Singnagtugaq, or “The Dream,” which is considered the first novel written in Kalaallisut. The text depicts the routine life of Greenlanders: disputes about dogs, falling in love, fights with Danish schoolboys, harpooning and shooting a whale, and dealing with colony managers.

In the end, the character Pavia dreams of Nuuk in the year 2105.

He is astonished that Greenlanders control their educations, have abolished the Danish monopoly, and enjoy democratic representation. Just yesterday, he is surprised to learn, there was even a vote on a motion to levy port dues on foreign ships.

Pavia is awed that Greenlanders can debate whether this will be good or bad for their economy and get to make the decision. In his vision of the future, Greenland is prosperous and freed from colonial afflictions.

We may not have to wait for 2105 for that future to start unfolding.

Denmark and the New North Atlantic: Narratives and Memories in a Former Empire. Edited by Kirsten Thisted and Ann-Sofie N. Gremaud. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2020.

Janne Flora, Wandering Spirits: Loneliness and Longing in Greenland. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Greenland in Arctic Security: (De)securitization Dynamics under Climatic Thaw and Geopolitical Freeze. Edited by Jacobsen, Marc, et al. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2024.

Niviaq Korneliussen, 2018. Last Night in Nuuk. Translated by Anna Halager. New York: Black Cat, 2018.

Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. Inuit. Toronto: The Royal Canadian Geographical Society, 2018.

Robert Rix, The Vanished Settlers of Greenland: In Search of a Legend and Its Legacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Søren Rud, Colonialism in Greenland: Tradition, Governance and Legacy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Mathias Storch, Singnagtugaq: A Greenlander’s Dream. Translated by Torben Hutchings. Hanover: International Polar Institute Press, 2016.

The Postcolonial North Atlantic: Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands. 2nd edition. Edited by Lill-Ann Körber, Lill-Ann and Ebbe Volquardsen. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Inst. der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2020.

Birgitte Sonne, The Worldviews of the Greenlanders: An Inuit Arctic Perspective. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2018.

Kirsten Thisted, “On Narrative Expectations: Greenlandic Oral Traditions about the Cultural Encounter between Inuit and Norsemen.” Scandinavian Studies, 73:3 (2001): 253-296.

Ebbe Volquardsen, “Can Trump’s bid for Greenland put an end to Denmark’s belief in colonial exceptionalism?” NORDEUROPAforum, January 24, 2025. Available at: https://portal.vifanord.de/blog/can-trumps-bid-for-greenland-put-an-end-to-denmarks-belief-in-colonial-exceptionalism/

Nicole Waller, “Connecting Atlantic and Pacific: Theorizing the Arctic.” Atlantic Studies 15:2 (2018): 256–78.