H. W. Brand's new book The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom is certainly timely. Brands engages contemporary discussions surrounding racial strife by examining two figures deeply connected to emancipation.

As its title makes clear, The Zealot and the Emancipator is a dual biography. Brands divides his story of Brown and Lincoln into four sections. He starts by briefly narrating the early lives and careers of the two men up through the mid-1850s, including Brown’s participation in the territorial violence between pro- and anti-slavery forces that became known as Bleeding Kansas.

The second section of the book turns to the political rivalry between Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, both from Illinois. Douglas was already a nationally-prominent Democrat who tried to tread a fine line by maintaining the rights of southern whites to own slaves while continuing to appeal to northern voters. Lincoln’s debates with Douglas during the 1858 Senate campaign thrust him into national prominence as an emerging leader within the new Republican Party.

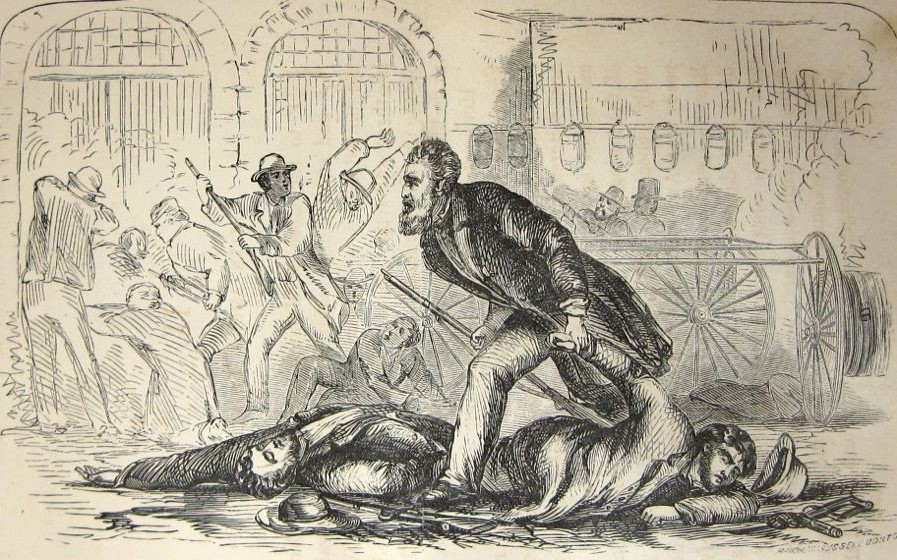

The book’s third section focuses on Brown’s 1859 raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in what was then Virginia. His subsequent arrest, trial, and execution led to Brown becoming a martyr for the cause of liberty. The book’s final section tracks Lincoln’s election and presidency through the Civil War.

An illustration of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, 1859.

Brands has written an engaging book that reads like a novel and is enlivened by many other voices from the period. As he pivots between the two central figures, he also interweaves other events from the struggle over slavery to flesh out the narrative. These include the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Preston Brooks wielding his cane to assault Charles Sumner on the Senate floor, and the infamous Dred Scott decision.

Brands deliberately organizes the story around these two “Great White Men,” and this choice left me wishing for a more diverse cast of characters. I can envision an alternative book pairing either of these men with someone like Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, or Dred Scott. This type of book would much more fully encompass the diversity within the anti-slavery movement of the 1850s. Instead, Brands follows a path already well-trodden.

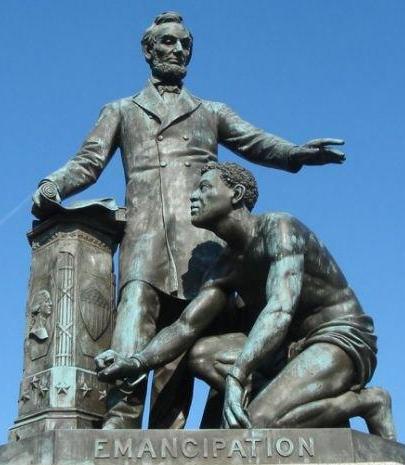

Although it was common in the decades following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination to identify him as the “Great Emancipator,” historians have long understood that this obscures and discounts the reality that many others played significant roles in the process of emancipation. First and foremost, enslaved people themselves seized the opportunity presented by the Civil War as a chance to obtain freedom by fleeing to Union lines.

Union generals such as Benjamin Butler and John C. Fremont committed Union forces to protect these newly-free people long before Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln clearly viewed slavery as a great national sin, but he was not an enthusiastic abolitionist. Instead, he was a pragmatic politician, who eventually realized that ending slavery would serve his primary goal of restoring the Union.

Any consideration of John Brown’s anti-slavery crusade must grapple with the question of when, or if, it is ever appropriate to engage in violence for worthy political or social purposes. Both the murders that Brown committed in Bleeding Kansas, as well as his famous raid at Harpers Ferry, would today be considered acts of domestic terrorism.

While Brown did not achieve his goal of sparking an immediate war of emancipation, his actions polarized white American public opinion into strong pro- and anti-slavery camps. Arguably this polarization led directly to the secession of southern states following Lincoln’s election as president.

Brands highlights the irony that notwithstanding Lincoln’s desire to resolve national disputes through the political process, he ended up leading just the kind of bloody war of emancipation that Brown had espoused. At the end of his life, Lincoln’s rhetoric of divine justice demanding retribution for the suffering of generations of enslaved people echoed Brown’s prophetic warnings.

This leads to the question of whether civil disobedience and direct action are effective in producing lasting change or whether progress can only come through established political processes. Brands seems to argue that enduring societal change only comes through government action. Not everyone will agree with that.

Anyone trying to make sense of the current problems facing the country needs to understand the long history of racial abuse and exploitation and those who fought to end it. Brands’ new book will help contribute to this understanding.