Historians have met the centennial of the 1917 Russian Revolution with a flood of new books which explore the Revolution and its long-term impact on Russia and the world. Laura Engselstein’s book, Russia in Flames, joins the chorus of publications on the Revolution. And yet, Engelstein’s book does much more. This formidable volume not only explores 1917 and its aftermath, but sets out to document Russia’s tumultuous trip into modernity. Beginning with Russia’s first attempt at Revolution in 1905, Engelstein offers thoughtful analysis of the Great War, 1917, and the ensuing Civil War which consolidated Bolshevik rule and created the Soviet Union.

The threads of these momentous events are tied together by several key themes. The most important, however, is Engelstein’s claim that the Bolsheviks emerged the victors because they embraced and institutionalized violence unlike both their imperialist foes and their socialist fellow travelers.

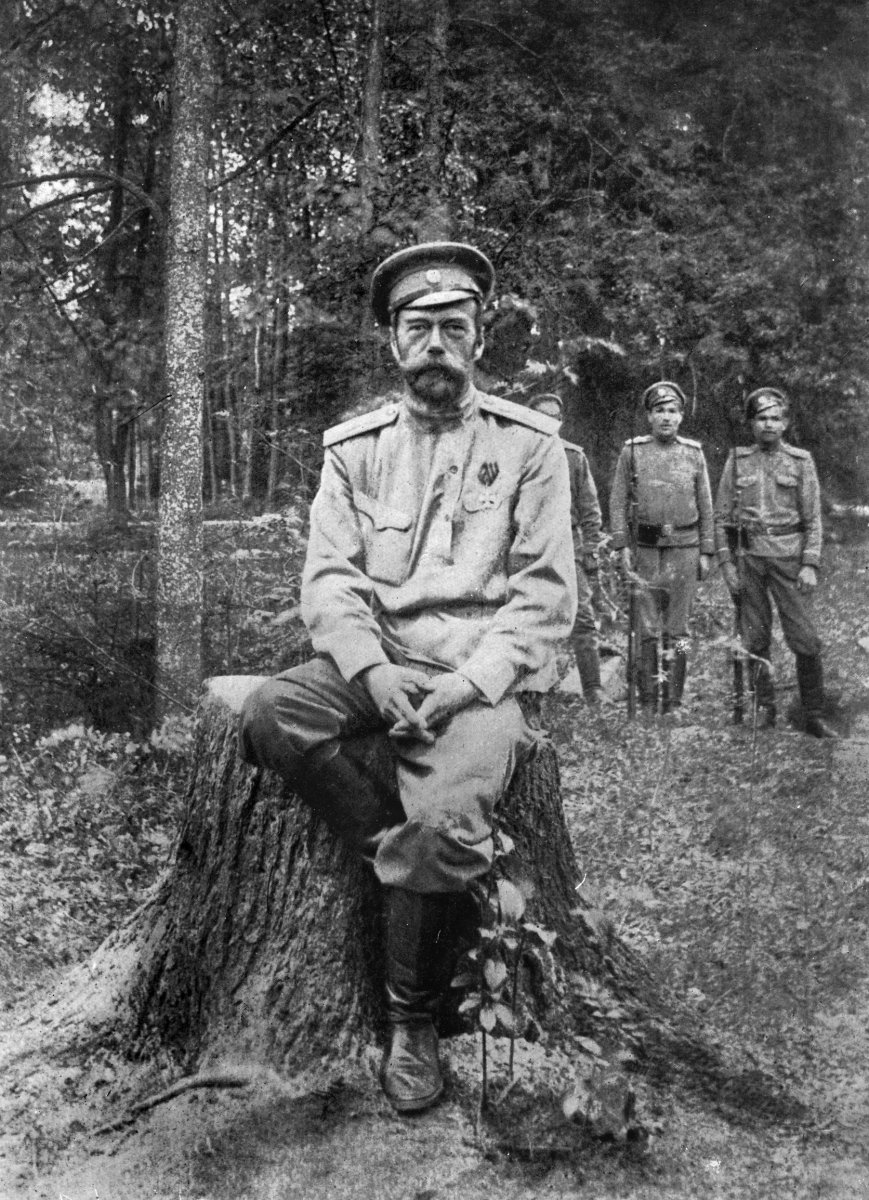

The two-year struggle of 1905 was the product of an autocratic state which failed to adhere to the rising tide of constitutional modernity. “The Empire had to embrace the very changes that threatened the basis of its rule.” Such changes would have included fostering a parliamentary system, civil society, and public opinion. By 1906, Nicholas was pushed into creating the Duma system, which finally fulfilled the growing cries for parliamentary elements of government. However, Nicholas endeavored to undermine the Duma for the remainder of his rule. While the changes wrought through 1905 quieted voices of dissent for a time, Engelstein suggests that it left an embittered and mobilized Russian public.

The Great War would prove to pull at the delicate seams of Russian society to their breaking point. Engelstein concentrates her analysis on the destabilizing effect that the War had on Russian society, making three major points. First, the War highlighted and intensified the monarchy’s failure to mobilize society at every level. Engelstein argues that the critical issue obstructing mobilization efforts was a breakdown of governmental and bureaucratic order on military and civilian fronts. This breakdown occurred partially because of real and imagined subterfuge from within the Empire, as well as a failure of centralization.

The failure of mobilization relates to Engelstein’s second point. Unlike the Germans, Russian leaders feared and resisted relying on nationalism to rally the troops for the cause. If anything, they saw nationalism as a threat and associated it with independence movements along the Empire’s peripheries. Finally, Engelstein addresses the pattern of violence that emerged from the Great War, a pattern that revolutionary and imperialist forces would follow in the subsequent Civil War. These factors coalesced in meaningful ways to expose the fault lines within the Empire.

In February 1917, the legacy of collective militancy combined with general economic crisis to produce a general strike in the capital cities. The strike began as a response to food shortages that were the result of mismanaged policy and rationing systems, and which had come to symbolize the litany of grievances urban workers had against the crown. The socialist parties debated how to respond to the unfolding events, and settled on rallying capital troops to mutiny against the monarchy. On February 27, some 170,000 soldiers engaged in a mass mutiny. The mutiny proved decisive, and Nicholas II abdicated from the throne just a few days later. This momentous event foreshadowed the central role of military mastery in the Revolution and Civil War that would follow.

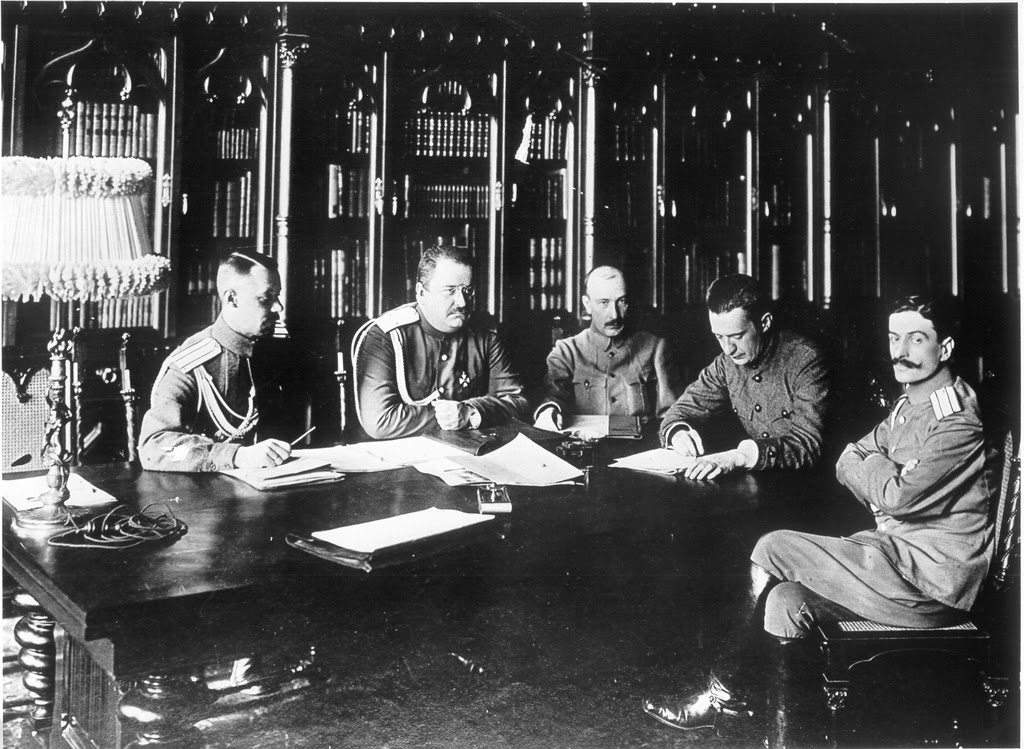

Engelstein lays out the events between February and the October Coup to highlight the growing tension within the socialist coalition government. While it did prevent a descent into chaos in the weeks following the mutiny, a number of factors strained the coalition’s united front. After the abdication some socialists, such as the influential moderate Pavel Miliukov, feared a crisis of legitimacy without a monarch. Furthermore, the question of Russia’s involvement in the Great War loomed over the Provisional Government. A key promise of February had been that Russia would immediately withdraw from the Great War, and under the guidance of the new Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, that promise was not immediately met. Miliukov and the more moderate forces meant to continue the war so that Russia could fulfill its initial promise of guaranteeing national self-determination for smaller nations. The slogan “Down with the War” was popularized and soldiers who felt no sense of loyalty to the Soviet or Provisional Government began to refuse orders. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March withdrew the successor government from the War, but magnified the country’s internal conflicts. It demobilized the old Imperial Army, whose soldiers quickly sided with or were recruited by various white and red forces in the impending Civil War.

Engelstein’s analysis of the coalition government’s collapse refutes the idea that it was the Civil War which distorted the “original character of the Bolshevik party.” She argues that violence and coercion were a key component of the Bolshevik character from the beginning, contending that Bolsheviks saw “civil war as the path to triumph.” Lenin returned to Russia in April, and in October, the Bolsheviks seized the Winter Palace and initiated the Civil War in full. It took three years of bloody conflict for the Bolsheviks to cement their dominance over the imperialists and various socialist coalitions. According to Engelstein, Lenin’s coup d’état and the Bolshevik victory destroyed any hopes for democracy within the Russian Empire’s successor state.

This book sheds light on the multiple revolutions that took place in 1917. The February Revolution did not guarantee October. February was brought about through the actions of a mobilized society which yearned for an ideal of democracy; October was brought about by a number of devastating internal and external factors which complicated the coalition government’s mission and made a more forceful way forward more attractive. Engelstein suggests that the Bolsheviks, from the beginning but especially from October 1917 onward, sought to construct the political arena in militaristic terms – through the army and the newly established secret police, the Cheka. They wove violence into the fabric of politics and stood unified when other socialist camps fragmented. Engelstein provides a thoughtful narration of events and it will appeal to both specialists in the field of Russian history and to general audiences that wish to unpack the rich and complex history of the Russian Revolution.