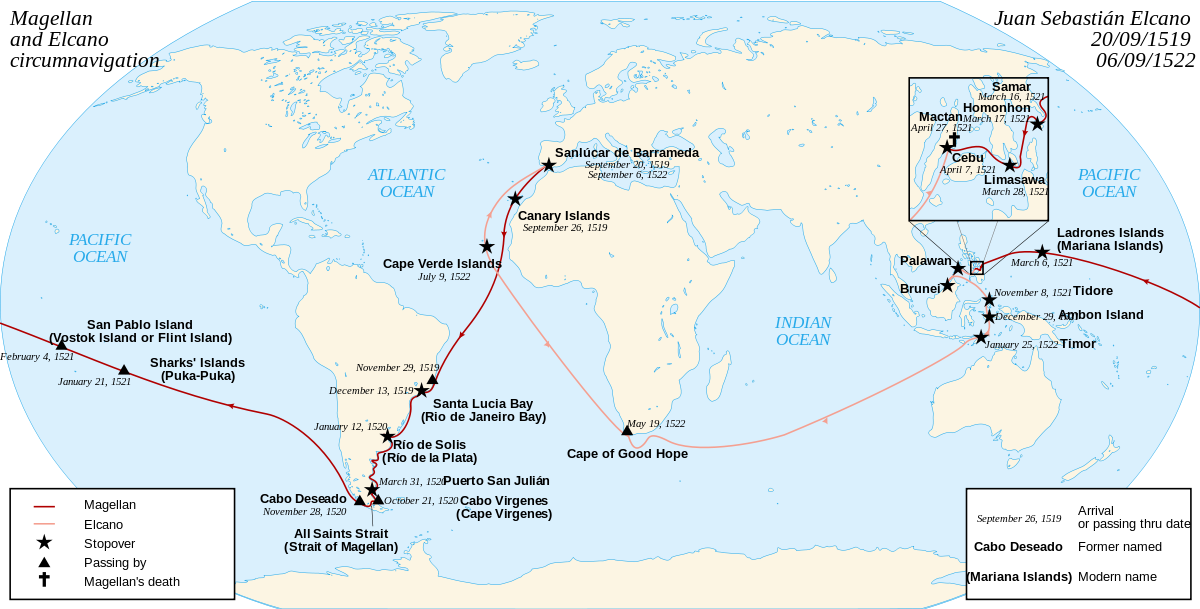

On September 20, 1519, five ships carrying about 270 men left the Spanish port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda sailing west — and kept going. Led by explorer Ferdinand Magellan, the armada’s goal was to reach the Spice Islands of Maluku (in the Indonesian archipelago) and open a new trading route for Spain.

Thus began the first recorded trip around the globe. An almost unimaginably difficult and perilous journey for the crew, Magellan’s voyage was the opening chapter in the rise of global trade and globalization that defines our world today. It also generated important scientific knowledge, including more information about the earth’s circumference and new understandings of global time.

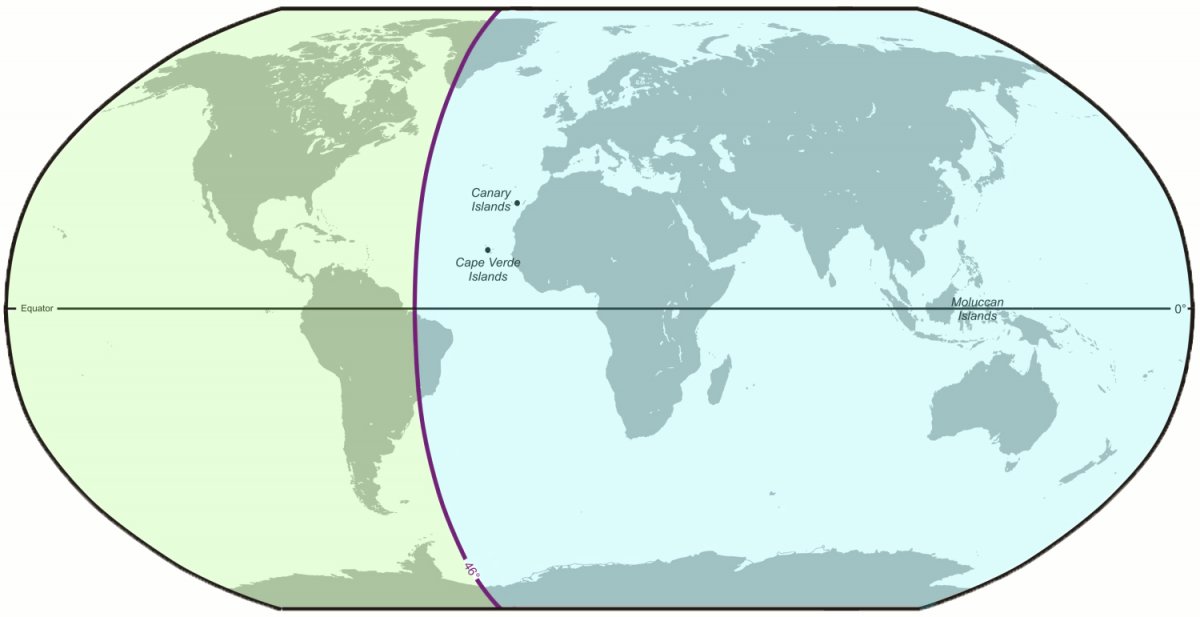

Establishing this new western sailing route was vital to Spain’s future as an international power. In 1494, after Christopher Columbus returned from the West Indies, the Spanish and Portuguese governments signed a deal known as the Treaty of Tordesillas in which the world was divided into two halves: Portugal could colonize and develop trade with Africa, Asia, and the East Indies, while Spain controlled the Americas. By 1515, then, the only way for Spain to access the luxury goods available in the Spice Islands and elsewhere in Asia was via a westward route.

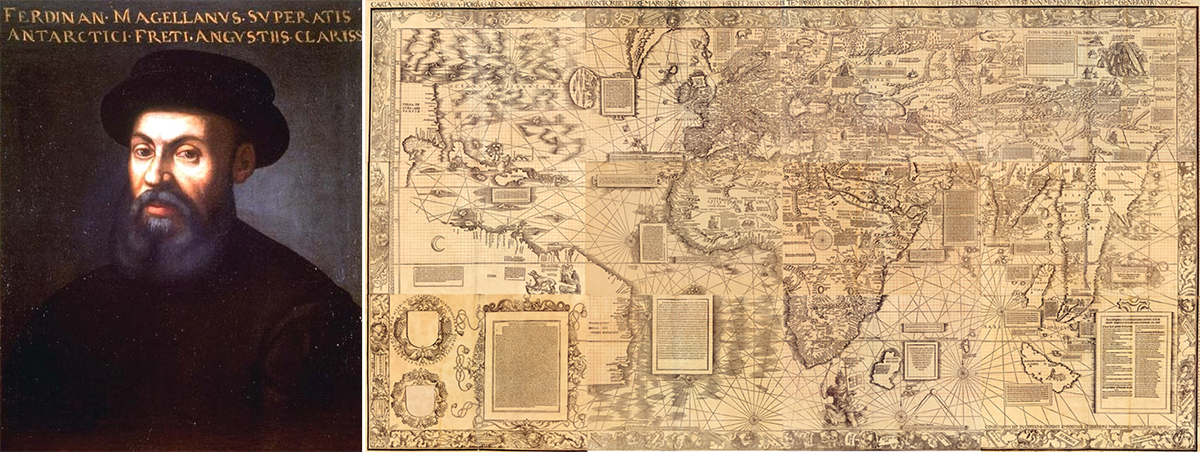

It was at this crucial moment that Ferdinand Magellan (Fernão Magalhães) arrived in Spain. A minor Portuguese noble, Magellan possessed an extensive knowledge of mapmaking and sailing, and already had years of experience sailing the Indian Ocean.

In 1513, Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa had marched across the Isthmus of Panama and confirmed that Asia and the Americas were separated by an ocean. Magellan was convinced he could sail around those continents and easily reach this ocean, accessing the Spice Islands beyond.

A posthumous portrait of Ferdinand Magellan, painted c. 16th or 17th century (left); a 1516 map of the known world at the time of Magellan's voyage (right).

Unable to convince the Portuguese of the importance of finding a route to the west, Magellan then turned to the new king of Spain, Charles I. If Magellan’s expedition was successful, Spain would have access to the goods of the East again.

Like most Spanish-funded endeavors, the people who sailed on this voyage were a diverse group, including German, Greek, French, and Afro-descended crewmembers. Besides Magellan’s Portuguese close friends and family, Spaniards and other Europeans with sailing experiences were brought in, some of them to work off debts. Magellan’s second-in-command was the Spanish overseer and accountant, Juan de Cartagena, and the chronicler was the Venetian Antonio Pigafetta.

Magellan and João Serrão were the only Portuguese captains, with Magellan in charge of the largest ship, the Trinidad, and Serrão at the helm of the Santiago. Spaniards captained the other three ships (San Antonio, Concepción, and Victoria), and constant Spanish scheming against the Portuguese would have grave consequences for the voyage.

A 19th-century illustration of Magellan's armada preparing to set sail in 1519.

Magellan did nothing to promote Spanish trust, keeping the route a tight secret until the ships were at sea. His plan relied on Portuguese sailing routes, which were well known to him but unfamiliar to many of his crew.

As the armada crossed the Atlantic, morale declined precipitously. By the time the ships arrived on the coast of what is now Brazil to wait out the Southern Hemisphere winter, many aboard were suffering from scurvy, and the Spanish captains were in open rebellion against Magellan. Mutiny was in the air, with Juan de Cartagena, who resented Magellan’s secrecy, leading the effort.

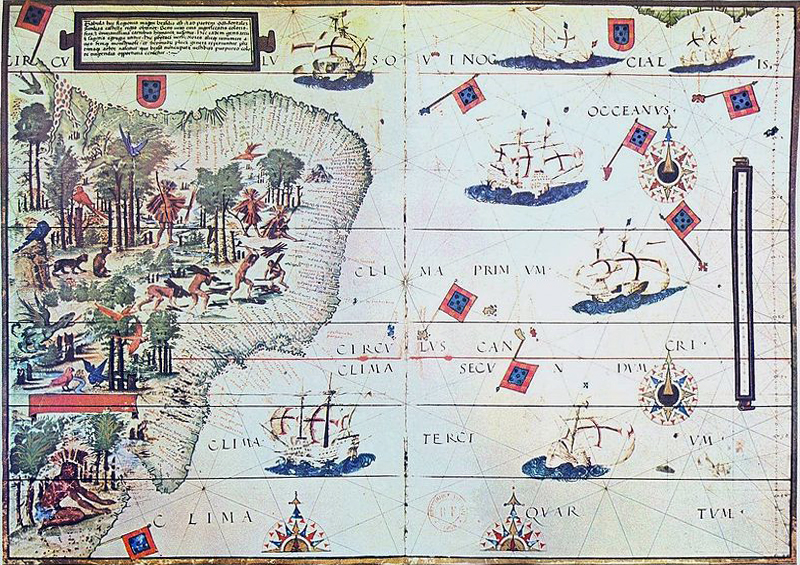

Brazil, as depicted in a 1519 atlas.

In the cold of their wintering grounds and with reduced rations, the mutineers made their move. Although they managed to take over as many as three of the five ships, they were eventually captured and Magellan exiled Cartagena to an uninhabited island off the coast.

The winter of 1520 also saw the destruction of the Santiago, which ran aground while on a scouting mission to the south. Although the ship’s crew survived, the loss of the Santiago put more pressure on an already pinched crew.

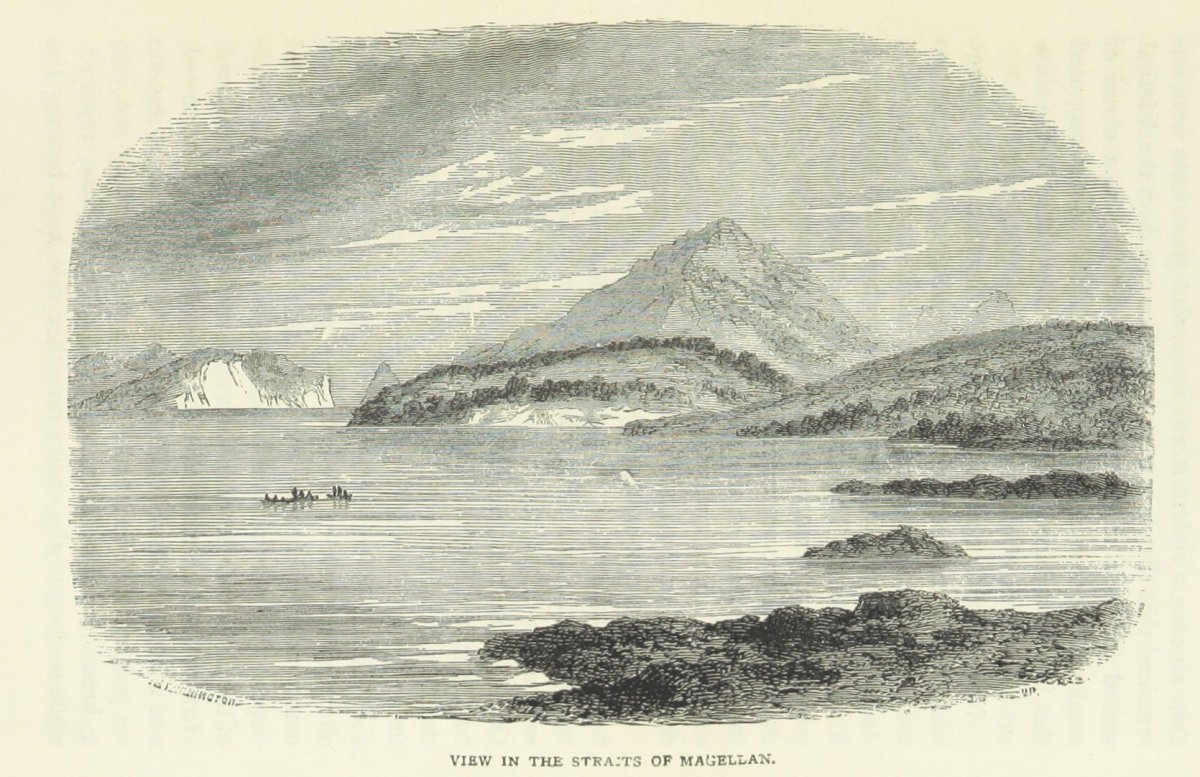

An 1885 drawing of the Strait of Magellan.

By late spring, surviving on seal and penguin meat, the armada entered what is now known as the Strait of Magellan, the narrow body of water separating mainland South America from the Tierra del Fuego. The armada lost another ship during the passage through the Strait: the San Antonio, which became separated from the rest of the armada, and turned around and returned to Spain.

An engraving (c. 1580–1618) of Magellan crossing the Strait that would bear his name.

Once the three remaining ships reached the other side of the Strait of Magellan, the sea they found was calm and placid. Magellan christened it the Pacific Ocean. Crossing the Pacific, the crew of the remaining ships suffered terribly. Twenty-nine sailors died during the four-month voyage.

In April 1521, the group put into an island in the Pacific: Cebu, in what is now the Philippines. As the first Europeans to see these islands, Magellan’s crew would lay the groundwork for the long Spanish colonization of the archipelago, which lasted until 1898. Magellan befriended the local ruler, Raja Humabon, and became embroiled in local politics, which would be his downfall.

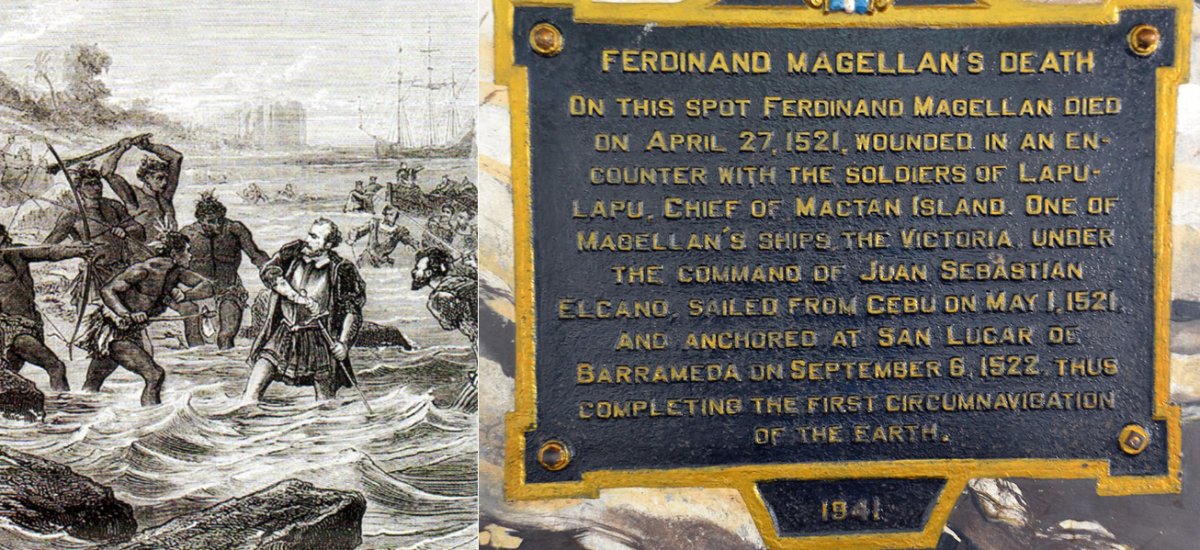

On April 27, 1521, Magellan went to war against the ruler Lapu Lapu on Mactan Island, who refused to bring tribute for Raja Humabon and the King of Spain. Fighting in the shallow waters off the shore, Magellan and 49 of his men squared off against over 1,000 Mactanese warriors. Facing such poor odds, Magellan was killed, as well as seven of his men, and his ships returned to Cebu.

A 19th-century illustration of the death of Magellan (left); a plaque in Cebu commemorating the site of Magellan's death, Philippines (right).

Raja Humabon, displeased at the newcomer’s loss, hosted a feast where he poisoned a group of some of the highest-ranking members of the expedition, leaving less than half of the original crew. The rest of the members set sail, fleeing to the safety of the sea. On May 2, 1521, those sailors who remained scuttled the Concepción and divided the crew among the remaining two ships, the Trinidad and the Victoria.

For the next six months the ships engaged in piracy as they made their way to the Spice Islands. Finally, in November, they arrived at the island of Tidore, part of the Malukus, and filled their holds with cloves. The Trinidad, which was taking on water, could not be repaired, and it was abandoned along with its crew.

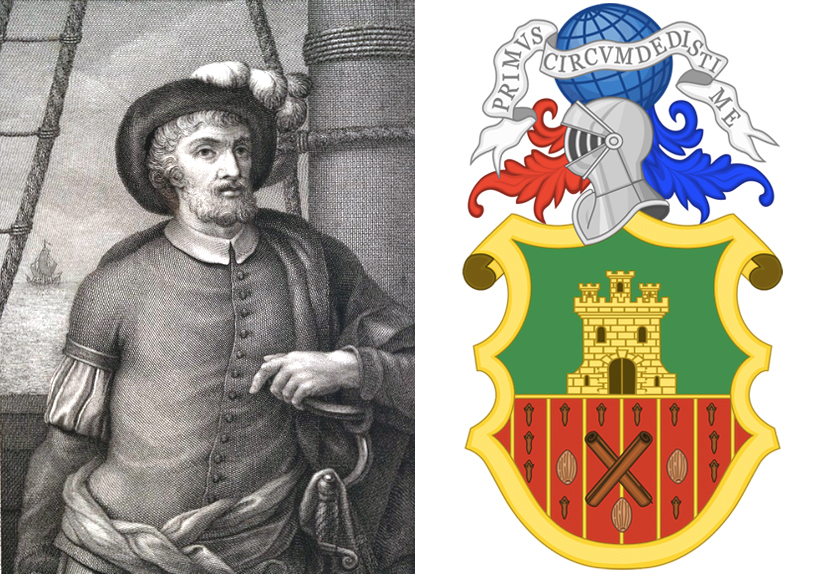

The Spaniard Juan Sebastián Elcano was elected captain of the remaining ship Victoria, which set sail west to the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. This voyage took over six months, during which the crew subsisted on rice alone.

On September 6, 1522, the Victoria at last reached harbor in Spain, nearly three years after first setting out. Of the original 270-strong crew, only eighteen had survived.

Map showing the route and chronology of the circumnavigation voyage from 1519 to 1522.

Although Magellan is remembered today for circumnavigating the globe, his reputation in the expedition’s immediate aftermath took a battering from those who had survived the expedition. Both the sailors of the Victoria, as well as the crew of the San Antonio who had turned back from the Strait of Magellan in 1520, disparaged him.

Juan Elcano, on the other hand, was given a hero’s welcome, even though he had joined the voyage only to receive a royal pardon. He was elevated to the peerage and added a globe and the words “first to circumnavigate me” to his coat of arms. In Spain, the circumnavigation is known as the Magellan-Elcano expedition.

Engraving of Juan Elcano, 1791 (left); Juan Elcano's coat of arms, bearing the phrase, "Primus circumdedisti me" ("First to circumnavigate me") (right).

The first recorded circumnavigation had important political, economic, and scientific consequences.

Spain calculated the total circumference of the globe for the first time, and determined that the Pacific was much wider than previously guessed, meaning that they owned some of the Pacific islands as demarcated by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Spain took control of the Philippines, and began exploration of the East Pacific.

Cross erected by Magellan's crew on the island of Cebu.

Magellan’s voyage also opened the door for trade. By the 1600s, Spanish territories produced most of the world’s silver, and around a third of it ended up in China through trade. This would have lasting effects on global strategy and economies, and propel Spain to the height of European power.

Perhaps just as important for us today, however, is the establishment of the International Date Line. Upon return to Spain, the sailors of the Victoria learned that they were a day behind in their reckoning. As they sailed against the Earth’s rotation, they lost hours. Many mysteries of the globe were revealed.