The Korean War isn't over. The truce negotiated in 1953 has yet to be converted into a formal treaty and this month historian Benjamin Young explores how the memory of this unresolved conflict continues to shape the outlook and actions of both North and South Korea.

On June 15, 1950, North Korean armed forces invaded South Korea and launched a brutal war on the Korean peninsula. The North Korean military nearly took over the entire peninsula, pushing South Korean forces to Busan. With the entry of U.S. armed forces, however, the South Korean military repelled the Communist attack and eventually pushed them north of the 38th parallel.

From July 1951 until the signing of the armistice on July 27, 1953, a stalemate characterized the conflict and neither side gained much territory. A peace treaty was never signed; the Korean War has never officially ended.

Despite its relative brevity, the conflict’s legacy continues to permeate the two Koreas, still divided across the 38th parallel. The unending nature of the Korean War has created a siege mentality on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), and this division of the two Koreas remains a regional security issue in global politics and a potential hotspot for military conflict between nuclear armed states.

The North Korean side has been institutionalized as a society permanently at arms and encircled by enemies. This siege mentality bolsters the legitimacy of the Kim family leadership and discourages internal dissent and political opposition.

A siege mentality also permeates the Republic of Korea (the official title of South Korea, ROK). The invasion of 1950 left an imprint on the South Korean psyche, resulting in militarization to a greater extent than most other liberal democracies.

For example, under the archaic National Security Law, North Korean literature and newspapers and pro-Pyongyang political parties are banned in the South. In many respects, South Korea’s liberal democracy, for all its successes, still sees itself under threat from a communist menace.

The Legacy of the War on North Korea

U.S. air bombing during the war left North Korea in ruins. American forces used more napalm during the three-year conflict in Korea than during the entire span of the Vietnam War. Today North Koreans remember the brutal U.S. air bombardment and vow it will never happen to them again.

During the war, the North Korean government encouraged its citizens to move to the mountains and live in caves. This association with mountains and the subterranean still influences North Korean military strategy. Much of the North Korean military infrastructure now lies underneath the earth in tunnels and subterranean complexes.

Bruce Cumings, a renowned historian of the Korean War, once referred to the North Koreans as “mole people” because of their technological prowess in tunnel building.

U.S. intervention during the Korean War has long provided ideological fodder for the North Korean regime. Americans are the permanent enemy of the Korean nation, and anti-Americanism is the guiding ideological principle of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (the official name of North Korea, DPRK). Portrayal of the U.S. government as an inherently imperialistic and aggressive force has long served the interests of the tyrannical government in Pyongyang.

A siege mentality and anti-Western paranoia define much of political life in North Korea. The Korean Workers’ Party, the ruling body in the DPRK, mobilizes people for annual anti-American holidays, such as the “Month of Joint Anti-American Struggle” in July and the “Day of Anti-U.S. Struggle” on June 25. North Korean educational materials are full of anti-American caricatures and passages.

By depicting U.S. foreign policy as neo-colonialist, the vast North Korean propaganda apparatus rallies citizens around the Kim family and deems them the ultimate guardians of the Korean people against American hostility.

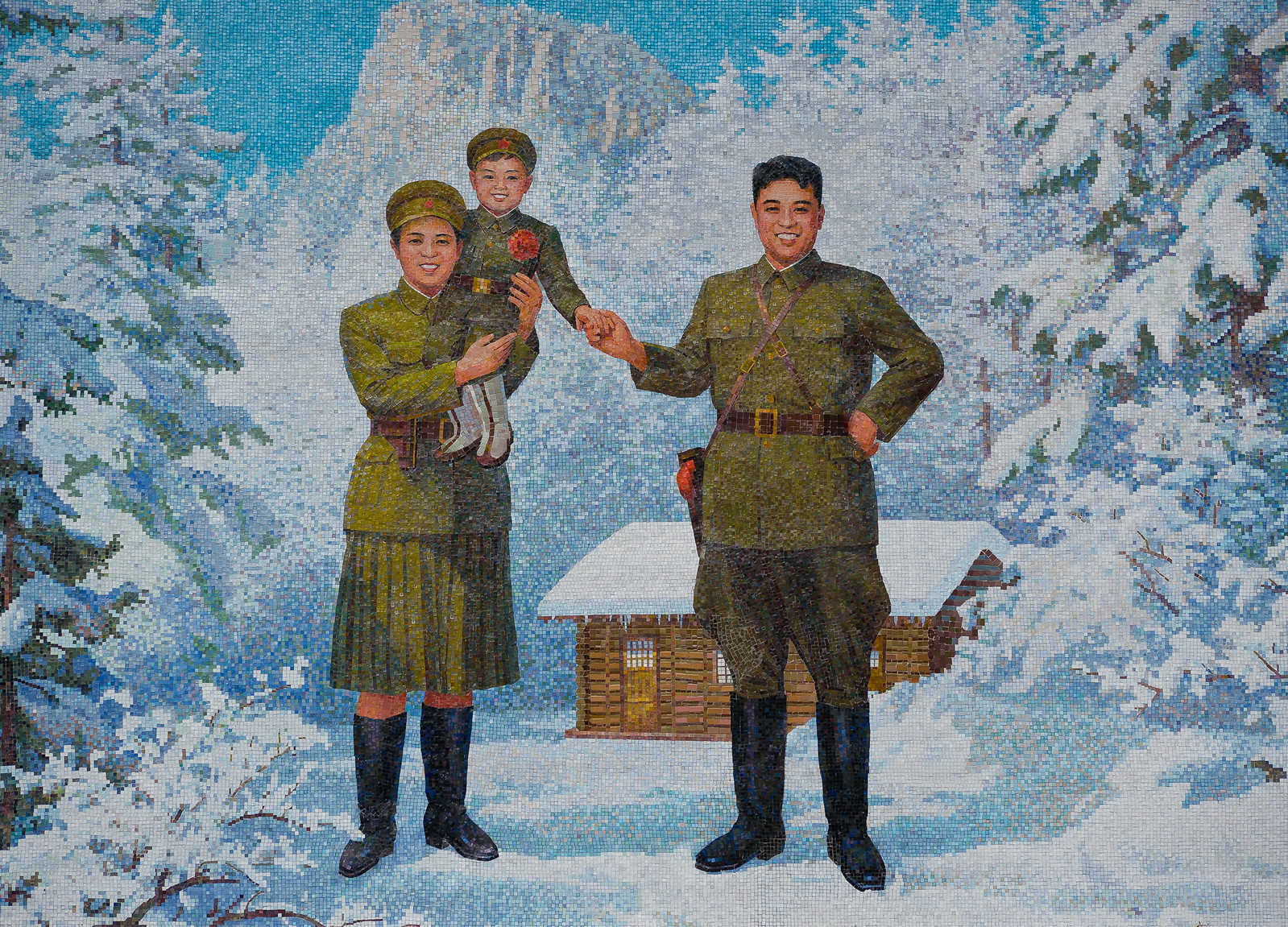

Anti-American sentiment has helped to solidify the hereditary succession of the Kim family regime from grandfather Kim Il Sung to his son Kim Jong Il and now his grandson Kim Jong Un. Represented in North Korean propaganda posters and textbooks as defenders of the Korean revolution, the Kims are often pictured in state media hugging and celebrating schoolchildren.

The North’s hereditary dictatorship preserves its iron grip on power by cultivating a personality cult around the Kim family. Depictions of the Korean War, known officially in the DPRK as the “Victorious Fatherland Liberation War,” deny the importance of Soviet or Chinese assistance in helping the North Korean forces. The supposed greatness and bravery of Kim Il Sung singlehandedly led the DPRK to victory against the U.S. during the war.

Interestingly though, the North Korean state traces its revolutionary origins not to the Korean War but to the 1930s anti-Japanese guerilla struggle. During this period, Kim Il Sung did in fact lead a resistance band against the Japanese colonialists in Manchuria. The North Korean propaganda apparatus has largely inflated the role of Kim’s partisans in the destruction of the Japanese Empire, but this period was indeed when Kim gained his nationalistic credentials as a Korean revolutionary leader.

The Korean War began as a civil war that evolved into an international proxy war. Both Koreas fought with the support and cooperation of outside world superpowers: China sent 3 million “volunteers” to help the Korean People’s Army (KPA) during the war. Human waves of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army turned the tide of the war in October 1950 and greatly assisted the fledgling KPA. Mao Zedong’s own son died during the conflict. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, reluctant to engage the U.S. in a direct military conflict, supplied weapons and equipment to the Communists.

South Korean forces fought under the United Nations (UN) umbrella with a coalition of nineteen other countries, including Colombians, Australians, South Africans, and Luxembourgers. The role of the UN in the Korean War still influences North Korean behavior, and Pyongyang holds a highly skeptical view of the UN as a neutral observer of inter-Korean affairs and often suggests in state media that the UN is a lackey of Western interests.

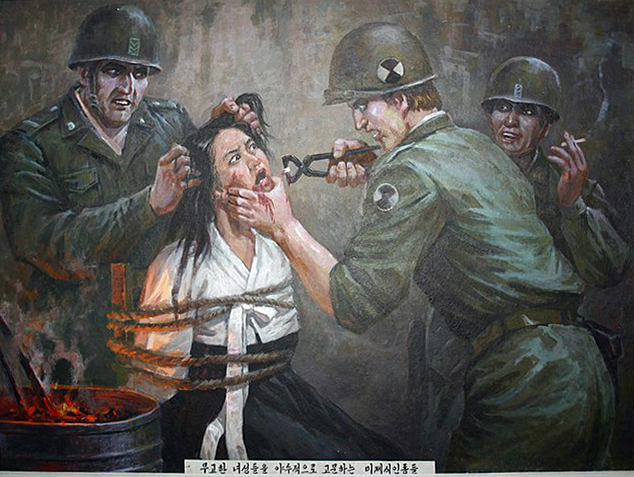

While Americans often regard the Korean War as the “forgotten war,” its legacy is part of everyday sociocultural life in the North. The North Korean propaganda apparatus, which dominates the cultural and social terrain of the DPRK, has even invented U.S. atrocities during the Korean War in order to buttress the dominant anti-American narrative of the regime.

The North Korean regime portrays the Sinchon massacre of Fall 1950, which killed some 30,000 people, as a U.S. mass killing of innocent Korean civilians. Yet, there is no historical evidence to support this assertion that American forces singlehandedly carried out this atrocity.

Nonetheless, the North Koreans built a museum in 1960 that is dedicated to remembering this event. Officially known as the “Sinchon Museum of American War Atrocities,” the North Korean government brings schoolchildren and other civilians on state-funded trips to this site. Complete with wax figurines of long-nosed, beast-like U.S. soldiers killing innocent Koreans, the museum provides an image of U.S. forces as cruel and ruthless killers. Koreans in this museum are portrayed as virtuous and heroic figures that defied all odds to defeat the American aggressors.

Since the Korean War did not end in the successful reunification of the peninsula under the Communist flag, Pyongyang relies on this myth that it was the Americans and its South Korean puppets that started the war and still seek the destruction of their system. The North Koreans are depicted as blameless and even righteous in this conflict. North Korean defectors living in South Korea often face confusion when presented with the historical evidence that it was Kim Il Sung who started the Korean War.

Pyongyang’s resistance to colonialism also deeply informed the regime’s post-1953 diplomacy. In the 1960s and 1970s, Kim Il Sung adhered to a foreign policy of solidarity and cooperation with other anti-Western nations. During the Cold War era, Pyongyang established diplomatic relations with a variety of newly independent countries. With its natural resources and nascent autocracies, sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, attracted North Korean diplomats and workers.

North Korean diplomats in Africa became infamous for trafficking ivory and arms. The North Korean government, committed to the cause of decolonization, supported national liberation movements with weapons, munitions, and advisors, and supported African development. For example, North Korea established agricultural farms in Tanzania and Guinea and sent agricultural experts abroad to other African states.

Despite its personality cult and tightly controlled political system, North Korea had one advantage over the South in appealing to developing nations. After Chinese troop withdrawal in 1958, the lack of foreign troops on North Korean soil bolstered the self-made image of the DPRK as a self-reliant socialist paradise.

During the 1960s and into the 1980s some governments accepted this narrative (though others saw that it was Soviet subsidies that kept the fledgling North Korean economy afloat). Under the rubric of juche, Pyongyang promoted the principles and values of self-sufficiency and autarky to other developing countries. Even the Black Panther Party in the United States adopted juche as an admirable trait for socialist revolutionaries.

The ideological fabric of North Korea was never strictly tied to Marxist orthodoxy. The regime mixed elements of ethnic chauvinism, Leninist centralism, Third Worldism, and revolutionary anti-colonial traditions into a distinct ideological blend. A nationalistic fervor has long penetrated North Korean institutions and has only intensified since the collapse of the Soviet bloc. This helps to explain the resilience of a highly centralized political system that has largely abandoned the communist ideals of world proletarian revolution and socialist internationalism.

The continuation of the siege mentality is what binds the North Korean system together. Without the constant threat of a U.S.-ROK invasion, the Kim family regime no longer has an outside power on which to blame economic woes. The hyper-militarization of North Korean society looks rational within this type of jingoistic mindset.

The Legacy of the War on South Korea

By the mid-1970s, it was clear that South Korea’s capitalistic economy was outperforming the centrally planned system of the North. The DPRK’s Stalinist-style economy became stagnant and its heavy emphasis on national defense depleted the coffers of the government. Massive spending on the personality cult also added to the national debt. Moreover, the Kim regime became off-putting to many foreign investors. In the mid-1970s, North Korea became the first Communist state to default on its foreign debts.

On the southern side of the 38th parallel, South Korea from the 1950s to the early 1980s was no shining beacon of liberal democracy. Contrary to most American textbooks, the United States did not fight for democracy during the Korean War but rather fought for anti-communism. Backed by the U.S. military, right-wing strongmen and state repression characterized much of Cold War-era South Korean politics.

South Korean autocrats often tried to justify their authoritarianism and the surveillance state by invoking the North Korean threat. North Korean guerillas semi-regularly infiltrated South Korean territory and DPRK commandos almost reached the ROK’s Presidential estate, the Blue House, in 1968. Some scholars refer to this period as the “second Korean War.” Nonetheless, the North Korean threat was often exaggerated by South Korean leadership during the Cold War era in order to deflect any criticisms of their dictatorships.

After the Korean War, the ROK and DPRK continued their competition in the international arena. The ROK adhered to a version of divided Germany’s Hallstein doctrine, where the North Korean government touted its staunch commitment to national sovereignty and independence while the South Koreans promoted their growing economic prowess and close ties with the United States as proof that they were the better Korea to establish relations with. Neither side could claim to be democratic nor politically pluralistic during this era.

From South Pacific island nations to the Caribbean, both Seoul and Pyongyang sent diplomats around the world in a bid to outdo the other. Sometimes diplomats from the two Koreas would visit the same head of state within the same day.

Seoul vowed to not establish diplomatic ties with any countries that formally recognized the North. Pyongyang, in return, did the same. The North and South represent themselves in international forums as the sole legitimate government on the Korean peninsula and neither side formally recognizes the other government.

Park Chung-hee’s tenure as ROK President from 1961 to 1979 ushered in a period of rapid industrialization as he successfully utilized the power of the country’s chaebol (corporate conglomerates) to rapidly grow the South Korean economy. Park’s government had a heavy hand in the national economy and pushed a capitalistic economic model known as the developmental state.

Today, South Korean corporations such as Kia, LG, and Hyundai hold global name recognition. No such comparison exists north of the 38th parallel, though North Korea does host the world’s only one-star airline, Air Koryo.

On the political front, Park’s government established the 1972 Yushin constitution which consolidated Park Chung-hee’s political power and dramatically reduced the already limited political freedoms in the ROK. The South Korean government had their own nascent personality cult dedicated to Park with photo exhibits and military parades showcasing his portrait.

The legacy of the Park dictatorship is still heavily debated in South Korea. Some see him as a leader that rapidly advanced South Korea’s economy despite substantial challenges, while others see him as a tyrannical autocrat who greatly limited political liberties and stymied the development of a free society.

In 1979, Park’s own security chief assassinated him, and political unrest subsequently defined South Korean politics. Chun Doo-hwan took power in the wake a military coup and, supported by the United States, he brutally cracked down on the pro-democracy movement in the early 1980s.

Ironically, some activists in South Korea’s pro-democracy movement looked to the North Korean ideology of juche for spiritual guidance and Kim Il Sung as an ideological torchbearer of self-reliance. Many of these pro-democracy activists viewed U.S. military presence on the Korean peninsula as an impediment to peaceful reunification. International pressure and rising support for the democracy movement among the South Korean public eventually pushed Chun Doo-hwan to give up power in 1987 and institute democratic reforms.

As the first ever country to go from international aid recipient to now an aid donor, the ROK is extremely proud of its dynamic economic transformation. Despite this rapid economic growth, the ROK still grapples with the North Korean provocations and increasing Chinese strategic dominance in the Indo-Pacific region. These external challenges intertwine with domestic politics as the left and right in the ROK tend to have grossly different ideas of how to deal with both Pyongyang and Beijing. The left and right political camps in South Korea are increasingly polarized and prone to disinformation campaigns. The siege mentality has now seeped into the domestic political space as well.

The Long Shadow of the War

Much uncertainly still surrounds the Korean peninsula. North Korea’s rapid nuclear development and belligerence threatens the security of Northeast Asia. North Korean state media has cited the deaths of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi as evidence that nuclear weapons are essential for securing regime security.

As a regime that sees itself as under siege, Pyongyang also cites “U.S. war provocations” as a reason for their nuclear armaments. Pyongyang regularly tests its ballistic missiles and has significantly advanced its asymmetric military capabilities.

North Korean hackers are well known for their technical skills and ability to generate revenue for the regime’s nuclear weapons program. Analysts and experts now estimate that North Korea holds somewhere between forty and fifty atomic bombs and could yield as many as 200 by 2027. A North Korean nuclear bomb could likely hit the U.S. mainland.

South Korea’s military has more technologically sophisticated equipment than the North, which is primarily composed of outdated Soviet-era tanks and artillery. Nonetheless, North Korea has one of the largest standing armies in the world and dedicates around 20-30% of its GDP to its military. The Kim family regime’s partnerships with both Moscow and Beijing could make any potential military skirmish on the peninsula into a global conflict.

And Russia and China remain vital to the economic and political security of the regime. Chinese economic investment and trade enables the North Korean regime to stay afloat. North Korea depends on China for around 80% of its external trade.

Meanwhile, Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine reignited the close diplomatic relationship between Moscow and Pyongyang. Russian leader Vladimir Putin met with Kim Jong Un in the Russian Far East while Russia’s Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu traveled to Pyongyang to view a DPRK military parade.

Openly flouting United Nations sanctions, Russia purchases North Korean artillery and short-range ballistic missiles for its illegal war of aggression in Ukraine. The cash-strapped North Koreans are all too willing to provide munitions for this conflict.

The North Korea threat is not an easy problem to solve for the international community. Many in South Korea no longer desire reunification as the sheer costs of it would be staggering and likely fall on the South Korean taxpayer.

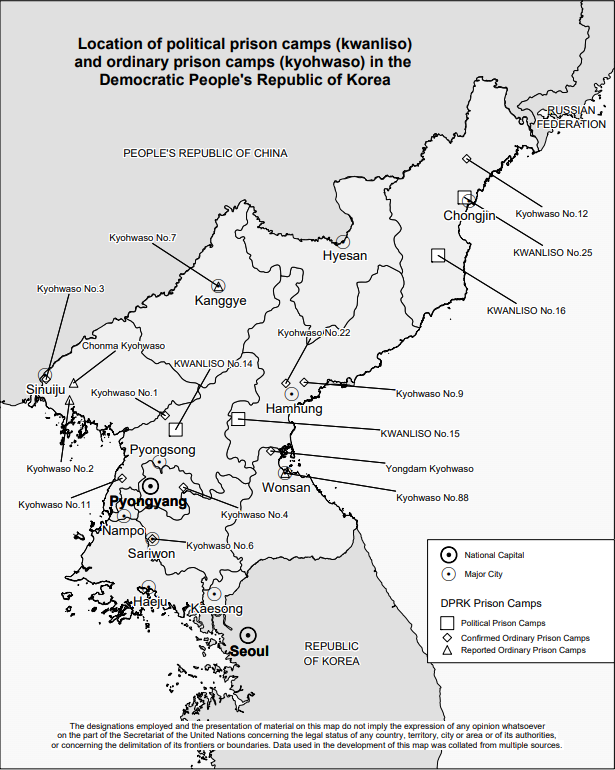

The DPRK system shows no signs of collapse and continues to rapidly develop its missile technology and military sophistication. Meanwhile, some 200,000 North Koreans are held in political prison camps and the DPRK is a human rights disaster zone.

While the North has descended into an even more brutal form of authoritarianism, South Korea became a global hub of culture, food, and commerce. K-Pop and K-dramas are internationally renowned and South Korea has become a thriving democracy in Northeast Asia. K-food can now be found in as far-flung places as Havana and Jakarta.

Nonetheless, on the South Korean side, some 28,000 U.S. troops are still based there. The U.S.-ROK alliance is often depicted as “iron-clad” and resolute. Donald Trump’s Presidency from 2016 to 2020 cast some doubt on this alliance as he questioned the importance of having U.S. troops based in such a rich country.

Joint U.S.-ROK military exercises still irritate the North, and Pyongyang regularly condemns these drills. Despite North Korean provocations and Trump’s recalcitrance, the U.S.-ROK alliance remains one of the most important and strongest security relationships for Washington.

The unending Korean War is one of the most palpable remnants of the Cold War.

An anachronistic regime, with its cultish leader worship and totalitarian political system, neighbors a dynamic and thriving economic powerhouse. The conflict is both a relic of a bygone era as well as a geopolitical hotspot that could suddenly jolt the world into a nuclear armed conflict.

Both societies are still contending with a siege mentality that has long permeated the psychologies of their leadership. The nature of a divided nation has unfortunately solidified this siege posture and shows no signs of retrenchment in the near future.

Adrian Buzo, The Guerilla Dynasty: Politics and Leadership in North Korea (London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 1999).

Gregg Brazinsky, Nation Building in South Korea: Koreans, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: WW Norton, 2005 updated edition).

Andrei Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Mitchel Lerner, The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Korea, 2002).

Dae-Sook Suh, Kim Il Sung (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

Balazs Szalontai, Kim Il Sung in the Khrushchev Era: Soviet-DPRK Relations and the Roots of North Korean Despotism, 1953-1964 (Redwood City, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2006).