Walking through the streets of the small town of Wittenberg, Germany, in 2017, it is easy to get the impression that the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation is a celebration of Martin Luther: Playmobil figures of Luther, Luther Christmas ornaments, and tote bags decorated with his image all focus attention on Martin Luther, the individual who stood up to the Roman Catholic Church and changed the course of Christianity and western civilization.

Commemorative Playmobil figure of Martin Luther.

But to stop at the tote bags is to lose sight of the complex web of factors that created the opportunity for Martin Luther’s initial actions and ideas to spread so far so quickly. And it is also to misunderstand why and how the Reformation sparked by Luther continues to shape our world today.

Coaster at the Wittenberg Brauhaus (brewery) commemorating Luther's wife, Katarina von Bora (left), and Luther-themed room decor at the Ringhotel Schwarzer Baer in Wittenberg (right). (Photos by Author)

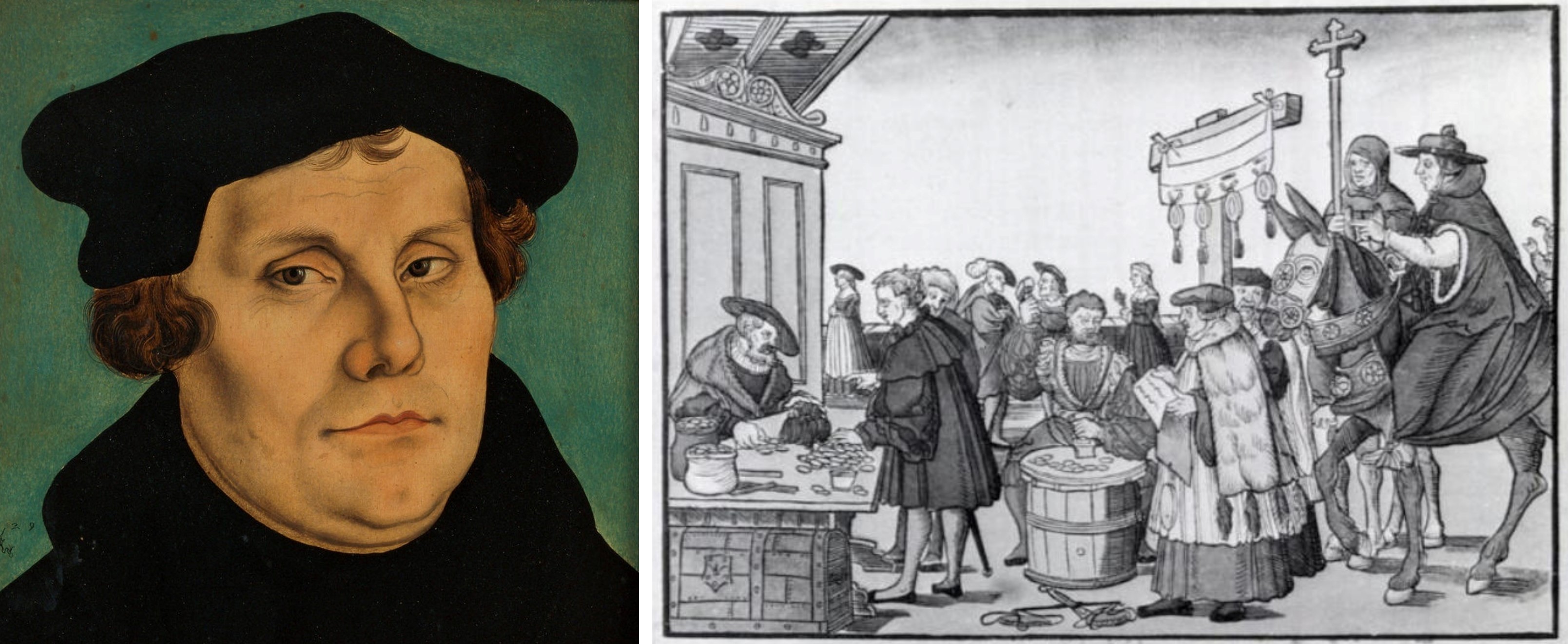

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, a monk and professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, circulated his 95 Theses—95 statements critiquing what he saw as papal abuses of power.

He especially criticized the recently developed church teaching that faithful Christians could buy an indulgence from the church that would shorten the time that they would have to spend in purgatory before being admitted to heaven. By 1517, Luther had come to see this teaching as a dereliction of duty on the part of the priesthood. His fellow clergymen, he believed, were leading trusting Christians astray, rather than showing them the correct path toward salvation.

Portrait of Martin Luther (left), and a depiction of the sale of indulgences, circa 1530 (right).

Luther was already a prolific and incisive theologian whose star was rising within the church. Having taken a highly disillusioning trip to Rome, he was engaged in a growing personal struggle with his own sense of the futility of a system of confession and penance that, he increasingly believed, could never account for the depths of his human depravity.

The bronze "Theses Doors" of the Castle Church (Schlosskirche) installed in 1858 to commemorate Luther's posting of his 95 Theses. (Photo by Author)

But Luther’s individual story, as compelling as it is, does not explain his impact.

Other clergymen before him had criticized the church, struggled with a sense of deep sinfulness, and provoked debate among Catholic theologians. In fact, in sharing his 95 Theses with his colleagues in Wittenberg—as well as sending a copy to the Archbishop of Mainz—Luther was following a longstanding medieval tradition of calling for debate within the university and clerical circles of the church. Within that context, posting his 95 Theses (whether on the church door or circulated among his colleagues) was neither a declaration of war against the church nor a proclamation of the establishment of a new Christian church.

But Luther’s articulation and publicizing of his 95 Theses occurred at a particular historical moment, within a particular context and web of relationships that shaped both his immediate impact and the long-term influence of his ideas and his actions.

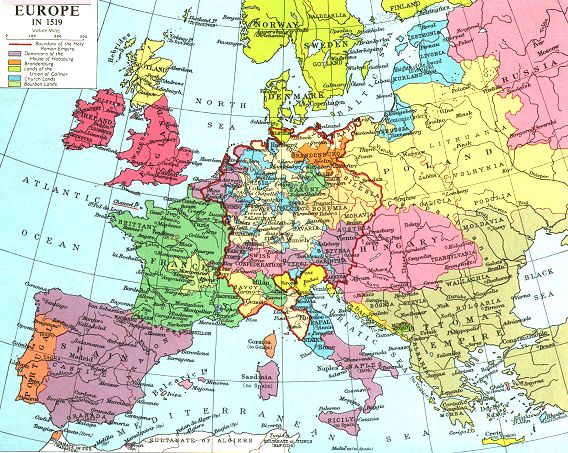

To begin with, in the initial years of response to Luther’s 95 theses, there was considerable political turnover and instability in large swaths of Europe. When Luther posted his theses in 1517, Wittenberg was part of the Holy Roman Empire, a loosely organized confederation of states and independent cities that owed loyalty to the emperor. In 1517, the emperor, Maximilian, was increasingly distracted by attempting to ensure—partly through bribery—that his grandson, who had just recently become the King of Spain, would be elected as the next Holy Roman Emperor.

In 1519, Charles became emperor and, at the age of 19, confronted both rebellious nobles in Spain and German princes and city councils aching to assert more independence from the Holy Roman Emperor.

Map illustrating the political division of Europe in 1519.

The confluence of this situation of political turmoil and Luther’s skillful leveraging of print technology allowed his ideas to spread faster and further, to more different kinds of people, than any previous critiques of the church.

But his success also depended on the existence of an interested audience.

This audience included participants in a literary and political debate about the role of women in society that had been reinvigorated as renaissance humanism spread from Italy into northern Europe. Luther himself corresponded with women on religious topics, held up marriage as a Christian obligation, and taught the notion that all Christians were spiritual equals in the eyes of God. (But he did not allow for women to become clergy.)

Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms, 1521.

As England was sorting out its own religious direction in the sixteenth century, Queen Elizabeth I became the Supreme Head of the Church of England—a situation unheard of in Europe to that point.

Thus, the Reformation energized a debate—prodded by women such as Katarina Schutte-Zell, Argula von Grumbach, and Marie Dentière—that continues to animate church culture across Christian denominations worldwide and that has implications for wider societal expectations regarding gender roles.

Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, circa 1588.

Consider also the global nature of the Protestant Reformation.

In his 95 Theses, Luther made no explicit mention of the world beyond Europe, and no claim to be speaking for non-Europeans. But when he shared these ideas in Wittenberg, the early phase of globalization had already begun. In 1517, Spanish people and military power had already been in the newly-christened “Americas” for 25 years. Vasco da Gama and his crew had reached south Asia nearly two decades earlier. Within two years, Ferdinand Magellan would begin the voyage that would first circumnavigate the globe, and Hernán Cortes would begin the invasion that would result in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire.

Portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh.

By the 1530s, it was clear that the centuries of a unified Christian institution in Europe had ended. As Europeans developed national rivalries to dominate trade, establish colonies, and even control the Atlantic slave trade, they were now working within the framework of competing visions of Christianity, traveling with missionaries seeking to convert local people to a particular form of Christianity. They were even arguing that their form of Christianity would make them better trading partners, as when Sir Walter Raleigh assured local people in sixteenth-century South America that the Protestant English were far better, more moral people than the Catholic Spaniards.

These Christian divisions shaped arguments supporting slavery and also, crucially, arguments to end slavery. In England, Quakers and Methodists—17th- and 18th-century outgrowths of the Protestant Reformation—were among the leaders of the abolitionist movement to end the slave trade and the institution of slavery.

Furthermore, the nature of modern arguments regarding the relationship between church and state developed in reaction to results of the Protestant Reformation. Later 16th- and 17th-century European governments faced, for the first time since the Roman Empire, the existence of competing groups that all defined themselves as Christian.

As the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) demonstrated clearly, tying political ambitions and authority to the dominance of a single Christian church was no longer a workable option. Governments seeking stability rather than endless civil war had to find a way to institutionalize some level of religious co-existence. The fact that they have not yet found a permanent solution does not change the significance of the Reformation in stoking the discussions, debates, and efforts to solve problems of religious heterogeneity and tolerance.

Depiction of soldiers plundering a farm during the Thirty Years War.

None of these long-term influences of the Protestant Reformation can be identified in Luther’s 95 Theses. In fact, he reacted strongly against any suggestion that his teachings led to demands for earthly social equality, such as the Peasants’ War of 1525, or that a faithful Christian society would be one that tolerated a variety of religious viewpoints, Christian or otherwise.

But despite Luther’s brilliance, charisma, and ability to make the printing press work for him, he himself is not the complete story of the Reformation, the impact of which has been shaped by many historical forces and has stretched far beyond what Luther could have imagined.