On November 4, 1924, voters elected the first woman governor in the United States. While two women previously held the office of acting governor for a short time—gubernatorial assistant Caroline B. Shelton of Oregon for a weekend in 1909, and later New Mexico Secretary of State Soledad Chávez de Chacón for two weeks earlier in summer 1924—November 1924 marked the “first” woman elected as chief executive of her state.

In fact, on Election Day 1924, voters in two states elected two women governors—Nellie Tayloe Ross in Wyoming and Miriam Amanda Ferguson in Texas. Each state claims “first” for these women. Ferguson had won the Democratic Primary election earlier that year, which at the time was but a technicality (Texas was largely a one-party state). Ross took the oath of office on January 5, 1925, fifteen days before Ferguson.

At quick glance, the 1920s looked like the perfect moment for women to gain the governor’s office. Their elections were four years after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which removed sex as a qualifier for voting. Two years later, the Supreme Court upheld that amendment in Leser v. Garnett (1922).

While it is essential to note that not all women gained the right to vote with the Nineteenth Amendment, and it took decades for the continued removal of additional voting restrictions, the amendment’s passage was a milestone in voting rights history.

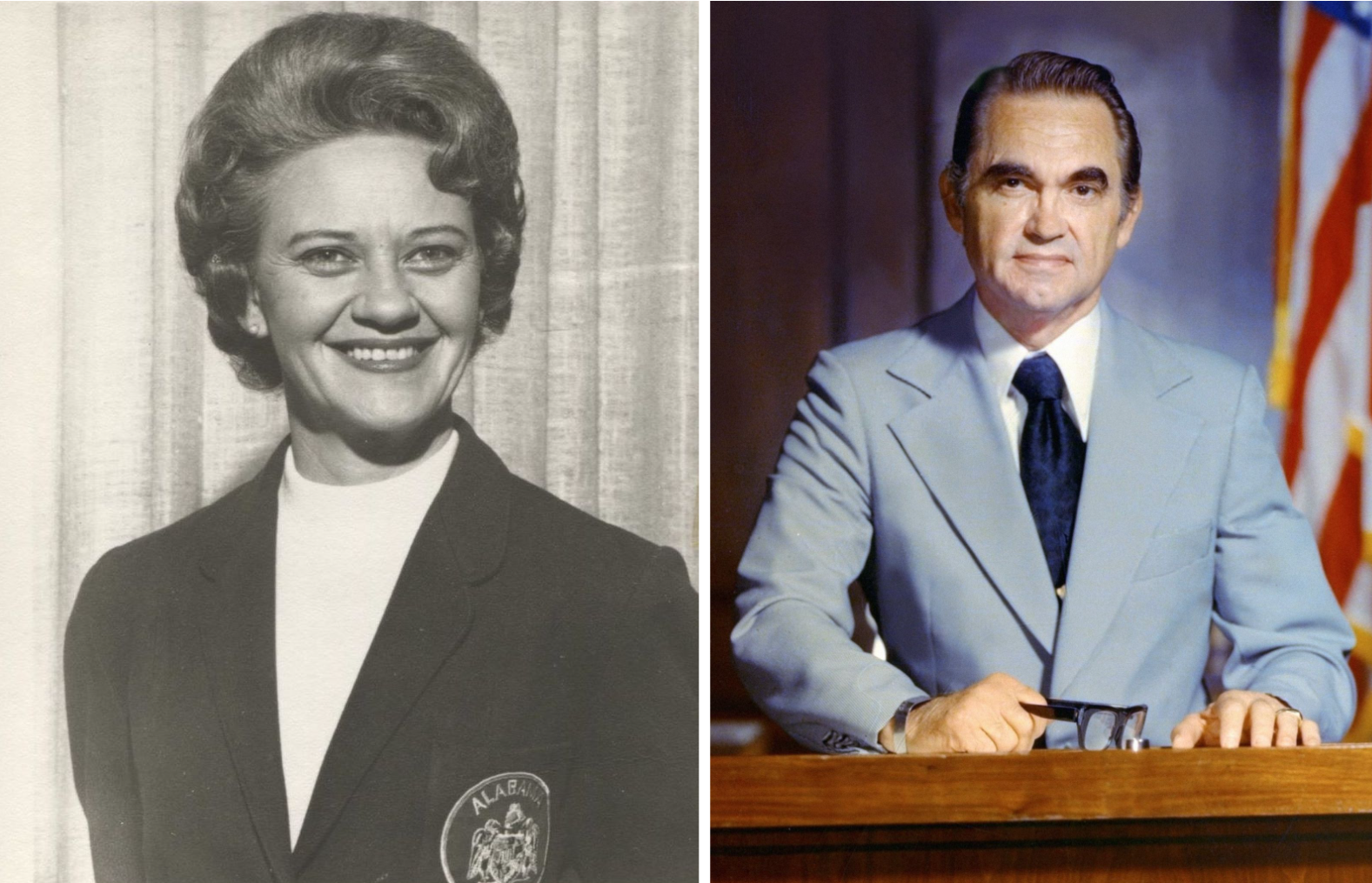

Neither Ross nor Ferguson were part of the woman suffrage movement or any other women’s political network. Instead, Ross, Ferguson and the third woman elected governor in the U. S., Lurleen Wallace in Alabama in 1966, were all three the wives of former governors whose husbands could not run again for office. All three campaigned on the idea of continuing their husbands’ unfinished business.

In Wyoming, William B. Ross died while governor in October 1924 from complications following an emergency appendectomy. The state’s Democratic Party leaders approached Nellie Tayloe Ross a few hours after her husband’s funeral; the election was the following month.

Ross did not campaign, but those who did so on her behalf made two major assertions: first, as the deceased governor’s widow she would continue her husband’s policies; and second, since Wyoming was the first U.S. territory, and later the first state, permanently to grant women the right to vote, it was only right that they should elect the first woman governor.

There was a concern that Texas might usurp Wyoming’s claim, if Ferguson won the gubernatorial election there. Eight days after Ross took the oath of office, the Wyoming Legislature convened for a little over a month. As promised, Ross continued her late husband’s policies and added several of her own.

In Texas, the Legislature impeached its governor, James E. Ferguson, in 1917 and subsequently barred him from election and holding public office in the future. Courts upheld the election ban, and thus in early 1924 James announced his wife, Miriam Ferguson, as a gubernatorial primary election candidate for the Texas Democratic Party.

Like Ross, Ferguson was also not a woman suffragist or previously politically active, and as governor her husband was so vehemently and actively anti-suffrage that suffragists served as a core of the coalition that worked for his impeachment. The Fergusons’ 1924 campaign focused on the message of vindicating their family after the impeachment, and they ran for office on the slogan “Two Governors for the Price of One.”

An enormously split state Democratic Party primary ticket with nine candidates opened the door for her eventual election by dividing the voter pool. Once in office, her husband placed his desk outside her office door and determined who went in, and largely what business occurred, and state newspapers discussed the gubernatorial appointments as “Jim’s.” There was little doubt who held the power.

In Alabama, while serving as governor from 1962-1969, George C. Wallace unsuccessfully worked to have the state’s constitution changed, which at the time barred a governor from holding consecutive terms. Like the Democratic Party chair in Wyoming and James Ferguson in Texas, George worked to persuade Lurleen to run in his place as governor so that he could maintain power.

As a result, critics claimed that her candidacy was an insult to Alabama’s constitution. The couple was clear: the intent was for George to continue to run the state’s gubernatorial business, which he did. Lurleen supported her husband’s policies, especially segregation, but like Ross and Ferguson she added some special interest issues of her own to the agenda.

In all three cases, Nellie Ross, Miriam Ferguson, and Lurleen Wallace ran for governor on the platform that they embodied a continuation of each of their respective husband’s work and tenure as governor. Therefore, each woman provided a way for those who were in power because of their husbands to remain in power. Their job was continuity, not change.

None of these three women governors were reelected at the end of their first terms. When Ross reran for office in 1926, she was no longer treated as the widow of the former governor, and her opponents’ gloves came off. She was a Democrat in a largely Republican state, and the election results that year proved it.

Ferguson also lost in her first re-election bid. Later in 1932, the Fergusons once again campaigned as a pair—“Ma and Pa Ferguson.” Ferguson won re-election one more time, as the Great Depression had hit voters hard and her incumbent opponent in the party primary took the blame. Miriam Ferguson’s second term made her the first woman twice elected governor in the U. S.

Lurleen Wallace did not lose a bid for re-election, but instead, she died in office. In 1961, during the birth of one of their children, the doctor discovered a malignancy. He told George, who chose for Lurleen not to know. Then in 1965, doctors officially diagnosed her with uterine cancer.

George and his political team announced her candidacy while she sought treatment quietly during her campaign, and as additional cancer was discovered, she continued to seek treatment after her election and throughout her year and a half in office. She died in May 1967.

It was not until November 5, 1974, that voters elected the first woman governor in the United States whose husband had not previously held that office: Ella T. Grasso of Connecticut.

Previously, she served as a member of Connecticut’s legislature, the state’s Secretary of State, and two terms in the U. S. House of Representatives. Her election as governor came as women leaders from both political parties and from across the U.S. gathered to form the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC).

One of the primary purposes of the NWPC was to encourage and support women to run for public office. October 1974 saw the passage of the federal Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), which barred certain types of financial discrimination including that based on sex and marital status.

The following year, in 1975, the United Nations declared “International Year of the Woman.”

Grasso’s election, as the fourth woman elected governor in the U. S., came half a century after Ross and Ferguson, and half a century from where we sit in 2024.

In the fifty years since the first woman was elected governor “in her own right,” dozens of women have held the office of chief executive in their own respective U.S. states, territories, and the District of Columbia. Women gubernatorial officeholders come from both major U.S. political parties. Since December 1983, there has been at least one woman in office as governor in the U. S., while many more “firsts” emerged along the way.

Even so, Americans have a strange relationship when it comes to electing women for executive offices. People are quick to claim victory once it has happened, but the choosing of a woman as the candidate by the party and powerbrokers, and the election of a woman in the role of chief executive by the voters, has long been a source of palpable discomfort.

As with women gaining the right to vote, it took generations to slowly chip away at the public rejection of the idea, to bring it around to increasing support, and finally to achieve eventual acceptance.

![]()

Learn More:

CAWP: Center for American Women in Politics. https://cawp.rutgers.edu

Jefferson Walker, “Public Servant and Southern Lady: Public and Private Tensions in Lurleen Wallace's Battle with Cancer,” Alabama Review, 67: Issue 2 (2014).

Jessica Brannon-Wranosky and Bruce A. Glasrud, Impeached: The Removal of Texas Governor James E. Ferguson (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2017).

Jon E. Purmont, Ella Grasso: Connecticut's Pioneering Governor (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2012).

Ralph W. Steen, “Governor Miriam A. Ferguson,” East Texas Historical Journal, 17: Issue 2 (1979).

Teva J. Scheer, Governor Lady: The Life and Times of Nellie Tayloe Ross (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005).

Tom Rea, “The Ambition of Nellie Tayloe Ross,” WyoHistory.Org: A Project of the Wyoming Historical Society. (2014)