Over six weekends in the summer of 1969, nearly 300,000 Black people gathered in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park for the Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of concerts celebrating Black music. A star-studded roster of artists appeared, representing Black sounds from West Africa to Motown and beyond. These performances are documented in the Oscar-winning 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

As that film shows, the Harlem Cultural Festival also affirmed the larger project of Black culture and politics in a period marked by both breakthrough and backlash. As participant Rev. Jesse Jackson told writer Jonathan Bernstein in 2019, the event expressed the “fierce pain and fierce joy” of a Harlem, and Black America, in transition.

The Harlem Cultural Festival demonstrates the centrality of Black popular music as both an expression and active part of the Civil Rights and Black Power era.

Additionally, like other such events, it refuted the racist belief that Black people could not gather without violence, a cornerstone of “law and order” rhetoric that bolstered “War on Crime” legislation and fears of Black militancy in the late 1960s.

Most importantly, it remains a resonant reminder of the importance of musical culture to both understand the present and transform the future.

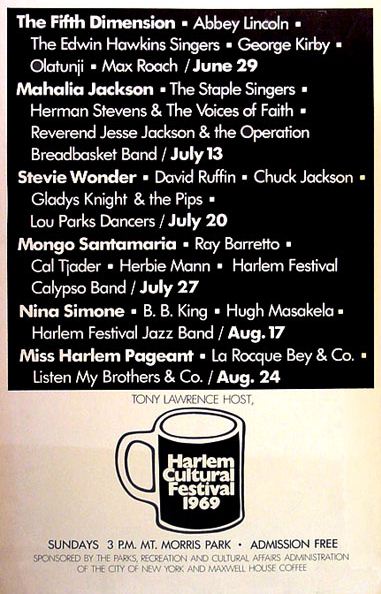

The festival began as the brainchild of Tony Lawrence, a St. Kitts-born performer and New York Parks Department employee, in 1967. After two successful smaller festivals, Lawrence expanded in 1969 thanks to corporate sponsorships and the support of New York Mayor John Lindsay, a progressive Republican popular with Black voters.

1969 was a complex moment. Even as the festival affirmed the victories of the Civil Rights Movement and the promise of Black Power and Afro-centrism, it also took place in the wake of repressions most vividly symbolized by the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose 1968 killing in Memphis provoked rebellions in cities including Harlem.

King’s memory created one of the festival’s most powerful moments. Gospel great Mahalia Jackson sang “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” King’s favorite song, accompanied by Mavis Staples and backed by Memphis saxophonist Ben Branch.

Additionally, Rev. Jackson spoke of the recent jailing of the Panther 21, local party members accused and ultimately acquitted of planning coordinated attacks. The Black Panthers provided security at the festival after the NYPD refused: the Panthers—routinely demonized as the cause of violence—worked effectively to protect the performers and keep the peace.

The presence of the Panthers, Mayor Lindsay, and Rev. Jesse Jackson signaled the expansive vision of a festival whose artists engaged with the Black freedom struggle in their performances. These included B.B. King’s piercing discussion of American history, “Why I Sing The Blues,” Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln’s diasporic dream “Africa,” and the Staple Singers’ urgent reminder “It’s Been A Change.”

Most direct, and most galvanizing, was Nina Simone. Simone performed the rueful “Backlash Blues,” her affirming anthem “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” and a version of her song “Revolution” accompanied by the call to action of David Nelson’s poem “Are You Ready?”

Even when the music did not explicitly discuss the Freedom Movement, the variety of sounds confirmed the assertions at its core.

Beyond the big stars, the festival included polished pop pros like Chuck Jackson, recent gospel crossover hitmakers the Edwin Hawkins Singers, South African bandleader Hugh Masekela’s urgent polyrhythms, Afro-Cuban jazz from Mongo Santamaria, and fiery jazz-rock from guitarist Sonny Sharrock.

Motown was well-represented, with performances from David Ruffin, Stevie Wonder, and Gladys Knight & The Pips. The festival also featured a high-energy set from crossover pop stars The 5th Dimension, climaxing with a gospel-infused version of their hit “Age of Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In” from the Broadway musical Hair.

This performance was not the festival’s only nod towards the counterculture.

San Francisco-based stars Sly & The Family Stone excited the crowd with their boundary-busting sound and appearance. That same summer, the group also appeared at another festival, bringing the same mix of pop, rock, soul, and funk that thrilled the Black crowds in Harlem to the mostly white audience gathered upstate at Woodstock.

Given these connections, it is no surprise that the Harlem Cultural Festival later became known as the “Black Woodstock.” They shared not only size and timing (and Sly), but their broader symbolism of a transforming cultural landscape.

Despite this, the Harlem Cultural Festival has not occupied the same cultural prominence as that more famous (and whiter) event. Though filmed by Hal Tulchin, much of the Harlem footage was unseen for fifty years, even as the Woodstock film mythologized that festival (and the hippie era) in cultural memory.

As Woodstock became a touchstone, remembered and often romanticized in the popular imagination, the Harlem Cultural Festival faded from view even as it remained potent for those who were there. This changed, thankfully, with the release of Summer of Soul.

The Harlem Cultural Festival is now understood as a cornerstone of a larger, valuable tradition of Black performance that fosters, in the words of scholar Daphne Brooks, “community revival, sustenance, triumph and renewal.”

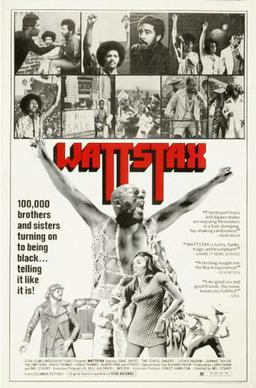

Contemporaneous events like the Watts Summer Festivals, which began in 1966 and which hosted the massive “Wattstax” concert in 1972, offered a counterpoint to narratives of urban disorder through demonstrations of Black cultural and political vibrance. Events like the 1971 “Soul to Soul” concert in Ghana or “Zaire 1974” strengthened connections with the African diaspora.

Through history, Black music has both responded to the world and built new possibilities for its performers and audiences. The Harlem Cultural Festival did that in its era, and now can do it in ours as well.

![]()

Further Reading:

Daphne Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Harvard University Press, 2023)

Tanisha Ford, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

Peniel Joseph, Waiting ‘Til The Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (MacMillan Publishers, 2007)

Emily J. Lordi, The Meaning of Soul: Black Music and Resilience Since the 1960s (Duke University Press, 2020)

Questlove, Music is History (Harry N. Abrams Press, 2021)

William Van De Burg, New Day In Babylon: The Black Power Movement in American Culture, 1965-1975 (University of Chicago Press, 1993)

Craig Werner, A Change Is Gonna Come: Music, Race, and the Soul of America (University of Michigan Press, 2006)