It has become fashionable for pundits to describe the relationship between the United States and China as a "new cold war." This month scholar Julia Keblinska uses movies and TV shows made in China to examine how the Cold War has been perceived by the Chinese, and how those perceptions have changed over time.

Over the past several years, the term “New Cold War” has mushroomed among analysts and commentators seeking to define contemporary geopolitics. Unlike during the Cold War, when China’s importance as an ideological adversary appeared relatively minor, the People’s Republic now is a major source of anxiety for American strategists.

During the Cold War (1947-1991), the Soviet Union was the most visible and feared socialist state. Indeed, the ideological conflict was considered bipolar, meaning that it was a contest between capitalist and socialist ideological camps, helmed respectively by the United States and the USSR. Even the periodization privileges a US-USSR Cold War narrative bookended by the declaration of the Truman Doctrine and collapse of the Soviet Union.

In 1947, China was already in the throes of an ideological “hot war” between the Chinese Communist Party (the CCP, backed by the USSR) and the Guomindang’s (GMD) Chinese nationalists (a capitalist regime ultimately backed by the US). The “loss” of China to communism was a stain on American military and foreign policy in the 1950s.

Unlike the Soviet Union, which has been a communist state since 1917, China in the first half of the 20th century had been a contested space in which many significant figures had close personal, cultural, and ideological ties to the United States.

The end date of the Cold War, 1991, also reduces the complexity of China’s rapprochement with the US. Nixon, after all, famously visited the country in 1972; the Shanghai Communique was signed during this visit. Calling for normalization in diplomatic relations between the two nations, and for bilateral trade, the document holds that “countries, regardless of their social systems, should conduct their relations on the principles of respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states.”

The Cold War in Asia might have been “won” by the Western side when the Chinese state embraced integration with the global economy in the 1980s and 1990s, but the Chinese regime did not collapse.

China’s emergence as a significant challenge to American power, however, seems to mark a difference between the Cold War and a new, multipolar world in which various geopolitical actors, including Russia and India, have shifted away from the American-led post-Cold War vision of the world.

Despite initial optimism in the United States that China’s politics would liberalize along with its economics in the 1990s and early aughts, the prospect of a wholly reformed Chinese state never materialized. By the late aughts, the CCP adopted a more confident and nationalist tone.

We should question whether it is useful to describe the new geopolitical situation as a “new” Cold War. The differences in the two situations are too great to suggest a continuity between the “old” and “new” Cold Wars.

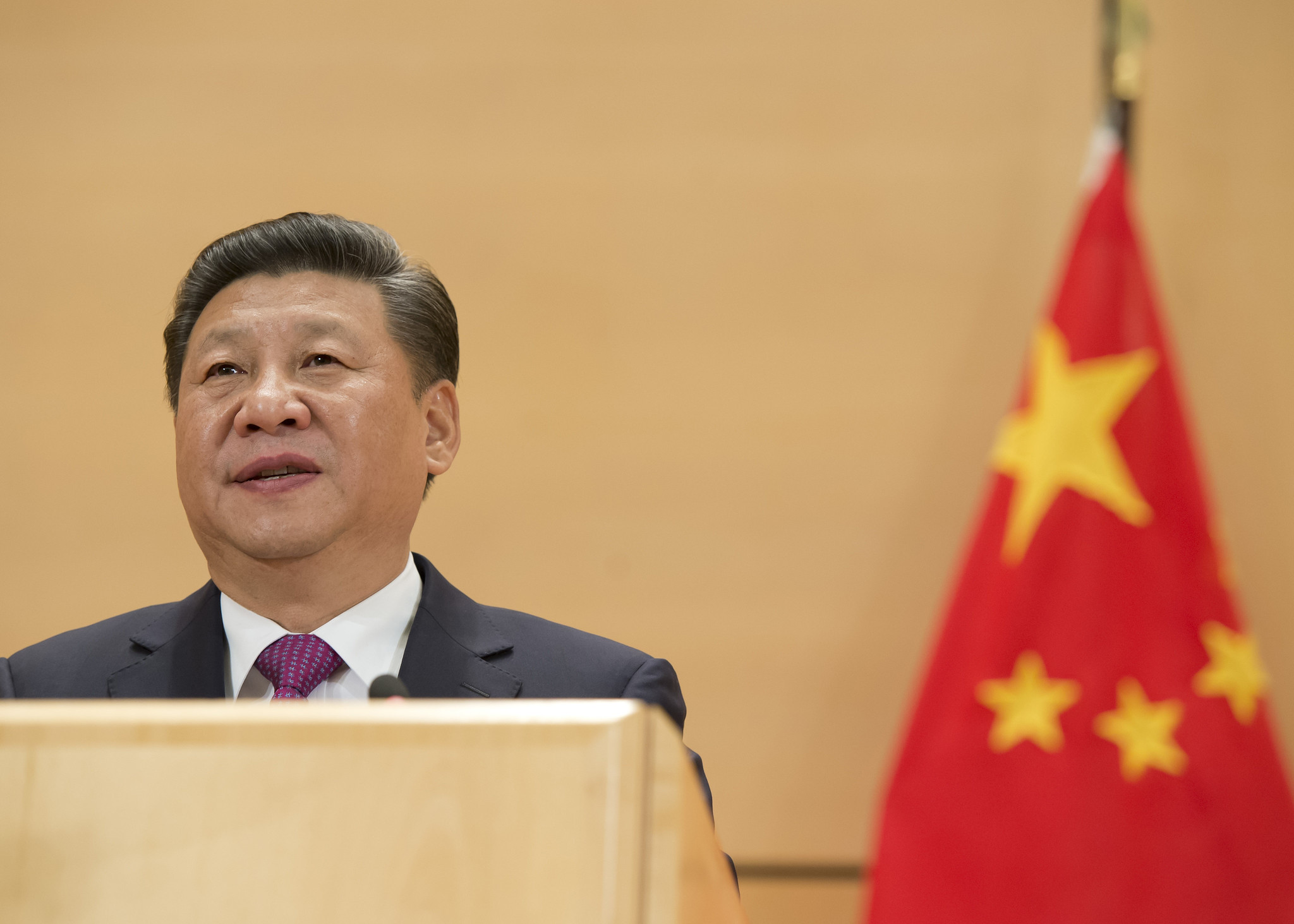

And yet, the rhetorical frame of the Cold War remains attractive. It is, after all, implicit in statements that present the United States as a democratic actor protecting the “free world” against totalitarian regimes headed by figures like the Chinese president, Xi Jinping.

In China, too, Cold War has once again become an evocative term, though it functions differently than in the West. Some do perceive newly heightened global tensions in terms of the New Cold War discourse, but “Cold War thinking” is also disparagingly used to describe Western commentary that resuscitates Cold War stereotypes to critique contemporary Chinese society and politics.

In other words, to invoke the “free world” in a polemic directed against the Chinese government can strike Chinese intellectuals as binary thinking that oversimplifies both history and the present moment.

Given that the Cold War, whether old or new, is a fraught but important term in contemporary thought about China, how has the Cold War been represented in recent Chinese cultural production?

Films, novels, and television shows can give us a sense of how historical events are understood and how they condition the present and the future. As anthropologist Heonik Kwon shows in his 2010 book The Other Cold War, the Western perception of the Cold War as an almost exclusively ideological (and concluded) conflict hides the reality of the period’s hot wars, with all their unresolved memories and traumas.

Shifting the perspective to Asia shows that China was not only a crucial actor in the global Cold War but a literal battlefield adversary for the United States in a way that the USSR never was.

Rethinking the Korean War

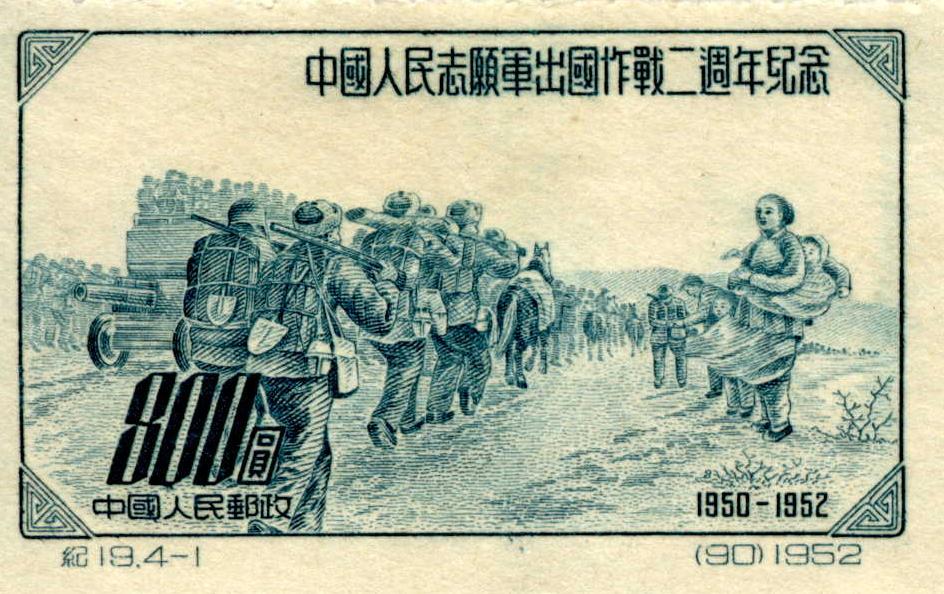

China’s entry into the Korean War (1950-1953), for example, merits reconsideration as a watershed event that dramatically changed American Cold War strategy and foreign policy.

In the United States, the Korean War is colloquially known as the “forgotten war” despite bombing campaigns that were unprecedented in scale and tremendous loss of life. In China too, despite an initial spate of war films, the Korean conflict had faded into obscurity as the nation embraced economic cooperation with the United States from roughly the 1980s onward.

As the post-Mao Chinese state attempted to reconfigure Chinese socialism to fit with global neoliberal economics in the 1980s and 1990s, calling attention to conflicts so strongly defined in Cold War terms wasn’t ideologically comfortable.

But now the ideological ground has shifted, and the Korean War is the subject of the highest-grossing Chinese film to date ($913 million box office).

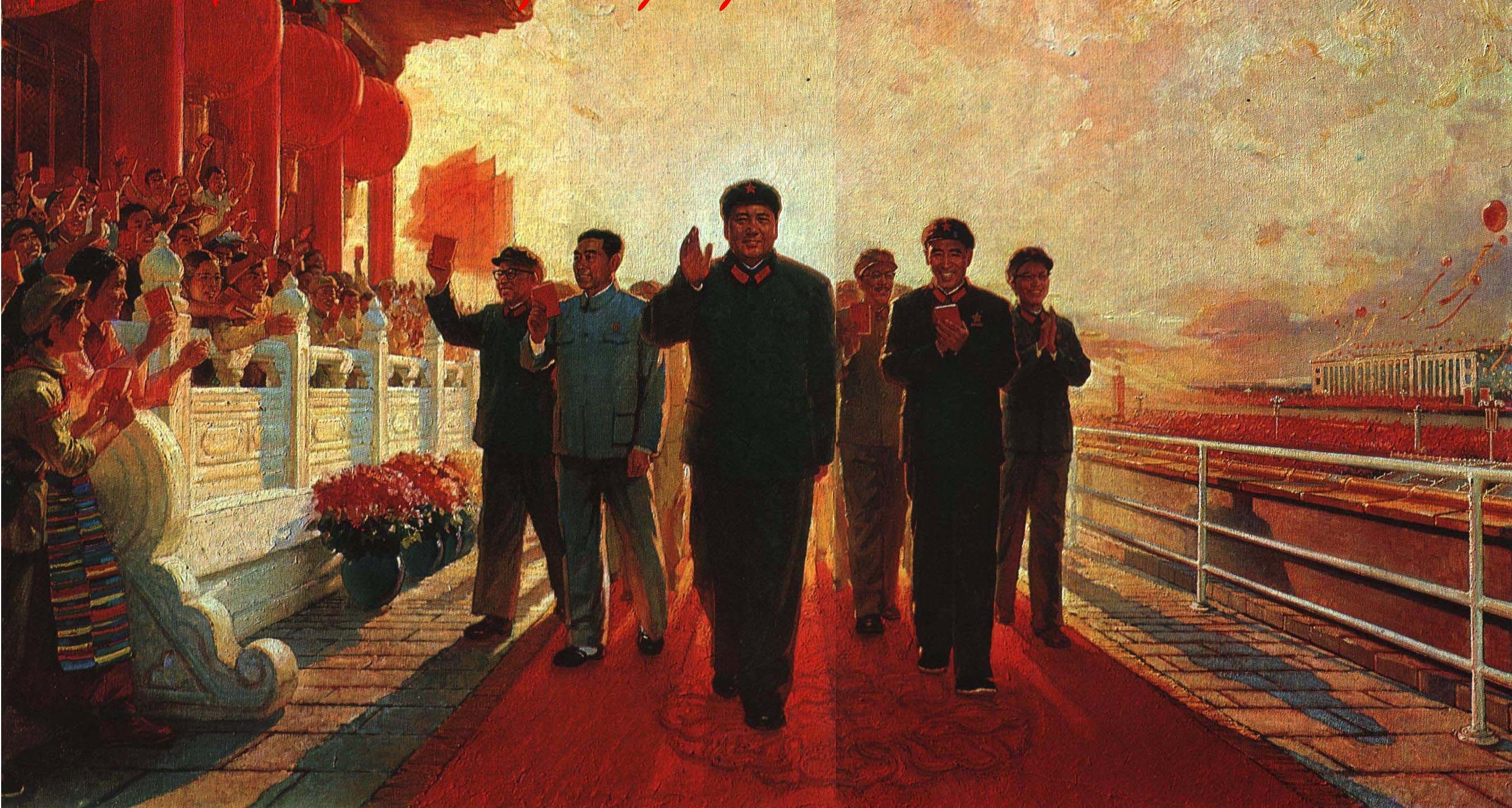

The 2019 Battle at Lake Changjin (directed by veteran filmmakers Chen Kaige, Dante Lam, and Tsui Hark) is a blatantly propagandistic war film. Its presentation of the historical event, known here as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, embraces a nationalist narrative and has been called into question both in China and abroad. The film is clearly not a historical document of the war (no war film is), but it does shed light on how historical narratives are constructed.

Battle at Lake Changjin presents the Korean War as an existential moment for China. After all, the People’s Republic was officially established in October 1949 after years of bloody civil war (1945/6-1949) resulting in economic devastation and millions of deaths, compounding the tremendous damage already suffered by China in the Second Sino-Japanese War and WWII (beginning with a Japanese invasion in 1937 and ending with Japanese surrender in 1945).

The film stresses unceasing warfare from the very beginning: a decorated soldier returns to his village to begin life in the new China in 1950. But before he can even settle in for a first night at home, he is given new orders to report to the Korean front. A parallel narrative in the film follows the country’s top leadership as they fear that the American military presence within miles of the Chinese border in Korea and across the straits in Taiwan augurs an imminent invasion.

China’s entry into the war in October 1950, a mere year after the People’s Republic was declared, is thus immediately characterized as a defensive action against American aggression.

The film is in fact so invested in the stakes of the US and China conflict that it does not feature a single Korean character and only rarely indicates that the front is in another country. The fact that the United States is fighting as part of a UN coalition of 16 nations is likewise obscured.

Predictably, the film presents the titular battle as a victory for Chinese forces who prevented an easy US victory and ultimately allowed Chinese and North Korean forces to push UN forces back to the 38th parallel, thus securing the Chinese border against American aggression.

Nevertheless, Battle at Lake Changjin strives not to antagonize the US. The film’s villain is the American lieutenant general Edward Almond, but so is his dramatic foil, major general Oliver Smith. At the end of the film, as Smith walks past the frozen corpses of Chinese soldiers who fought at Changjin/Chosin, he remarks that the US “was not ordained to win” against such “strong men.”

The film walks a fine line. It presents the successful confrontation with America as a foundational narrative for the PRC. Anti-American rhetoric, however, is curbed, as Americans are ultimately shown to respectfully recognize Chinese bravery on the battlefield.

A Cold War genre like the Korean war film had clear ideological coordinates in the Chinese socialist period (1949 – 1980s, roughly the same with the historical Cold War). Such values were imported into this blockbuster to map a new, future-oriented narrative that relies on the historical Cold War to establish a confident geopolitical position for the film’s millions of Chinese viewers today.

The Korean War is one of several foundational moments in the Cold War for both the United States and China. In a PBS documentary on Chosin, historian Bruce Cumings asserts that American leadership was so shocked by the setback exacted by the Chinese in December 1950 as to dramatically change geopolitical strategy: Chosin led to “fundamental changes in, in American history. That built the national security state, built military bases abroad, a large standing army for the first time in US history. And all of that transpired in December 1950 courtesy of the Chinese intervention.”

In this interpretation, China is central to Cold War history and the Cold War is a significant factor in Chinese history as well. And yet we tend to think about the socialist period in China through the lens of “totalitarian brainwashing” rather than really considering how external threats like the Korean and Vietnam Wars radicalized domestic politics.

Communist leaders oversaw destructive and paranoid campaigns to root out political enemies (the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957 and the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976), but fear about foreign influence was not irrational given that two US wars that threatened to destabilize Chinese politics were fought in neighboring states in these periods.

The point here is not to diminish the violent excesses of China’s political campaigns in the 1950s and 1960s, but rather to shift perspective and ask how Chinese political and domestic culture interacted with the Cold War. Thinking through the Cold War allows us to move past an analytical impasse that colors thinking about China in binary, good/evil terms.

If the kneejerk conclusion is almost uniformly to decry the Chinese state as an agent of paranoid control, it is difficult to see the political and historical complexity that Chinese people living and consuming culture in the People’s Republic navigate.

Indeed, we tend to still assume that Chinese people who embrace nationalist (and/or anti-Western) rhetoric are at best oppressed and at worst brainwashed. This position is not only demeaning to the intellect of the Chinese people, but it also rests on a vision of Chinese history that refuses to see domestic turmoil in terms of global processes.

3 Body Problem and the Cold War, Old and New

The science fiction series The Three-Body Problem is undoubtedly China’s most well-known literary export of the 21st century. Now a “universe” in the same sense as the “Marvel Cinematic Universe,” writer Liu Cixin’s novel was originally serialized in 2006.

The subsequent stand-alone novel (2008) was popular, and an English translation was commissioned by the China Educational Publications Import and Export Corporation, a state-owned educational publisher. The Three-Body Problem was first published in English in 2014, with sequels and international awards following.

In 2023, it was adapted for Chinese television by Chinese Central Television (CCTV) and Tencent under the title Three-Body. An American adaptation, 3 Body Problem, premiered on Netflix in 2024. Skeptical Chinese fans’ scrutiny of this version was in turn critically analyzed by Western media. The series and its reception, observers remarked, offer crucial lessons about China’s past and present.

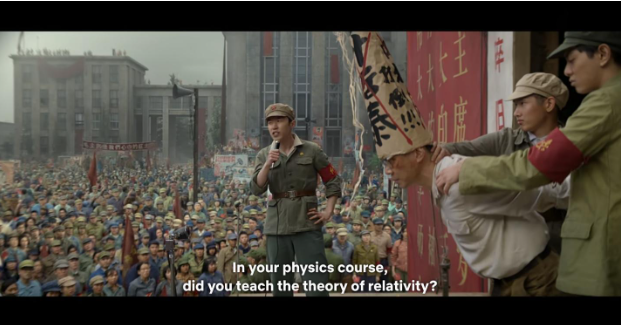

Unlike the Chinese adaptation, the American version begins with a harrowing Cultural Revolution struggle session in which Ye Zhetai, a physics professor, is denounced and brutally killed by radicalized students who object ideologically to the theory of relativity.

His daughter, Ye Wenjie, observes from the crowd. She is distraught, but she cannot save her father. Almost everyone around her clutches Mao’s Little Red Book and enthusiastically celebrates the denunciation on stage. His death (and her mother’s complicity in denouncing him) is the first of two major betrayals that condition Ye’s ultimate decision to invite destruction on humanity.

Several years later, as a sent down youth working in a logging camp, she befriends a young journalist. He shares Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring with Ye, and the two form a friendship and romantic attachment due to their shared concern over environmental destruction. When the forbidden book is discovered by authorities, however, the young man balks and lets Ye take the blame for possessing contraband.

Ye is given the opportunity to denounce her father’s colleagues to escape punishment, but refuses. Instead, she takes the authorities up on an offer to work at a secret military radar facility, known as Red Coast, where her skills as a physicist can benefit the nation. Eventually, she uses Red Coast’s giant radar to communicate with an alien race, the Trisolarians.

Though she has been warned by a peaceful Trisolarian that further communication will invite invasion from his resource-starved compatriots, Ye chooses to send another message, effectively inviting the aliens to invade Earth. Her reasoning is straightforward: humans, capable of cruelties like the madness of the Cultural Revolution, don’t deserve dominion over the planet.

This narrative structure evokes “scar literature,” a late 1970s genre in which victims and perpetrators processed their trauma through literature about the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

Liu Cixin’s original draft of The Three-Body Problem (and its English translation) begins with the same show trial and likewise presents the madness of the Cultural Revolution as the instigator of apocalypse. On the advice of his Chinese publisher, who was wary of censorship, Liu moved the scenes to the middle of his book, thus dulling their sensational impact.

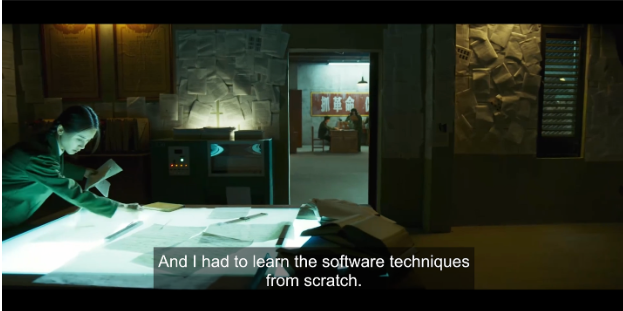

Unsurprisingly, the Chinese television series likewise does not begin with a Cultural Revolution show trial. A high-profile TV show could hardly wade into such controversial territory in 2024 as China becomes ever more wary of internal political dissent. Instead, the CCTV Three-Body shifts narrative and aesthetic registers away from trauma to Cold War intrigue.

The program begins with a tense sequence in which we see Ye Wenjie navigating a Cold War era military facility. She manually decodes a message printed on ticker tape. The exhortation “Do not reply,” flickers on an analog computer screen. Ye ignores this warning and proceeds to a control room, where she presses a red button and sends an invitation out into the universe.

In this opening gambit it’s a little red button, not the Little Red Book, that spells apocalypse.

The Cultural Revolution setup is notably absent in the opening of the Chinese program, but ideology is not. Ye’s trek through the base to send the fateful message is set to the tinny tones of loudspeakers playing choral “red songs” that exhort the communist mission. Nevertheless, this sonic political “excess” is thoroughly embedded in a Cold War space.

Yes, the song is eerily evocative of oppressive politics (though many Chinese viewers might find it nostalgic), but the opening sequence is clearly generically coded as a thriller in which a rogue operative uses military assets to communicate beyond enemy lines. It’s also a display of Chinese technological prowess, which is a major function of the Chinese adaptation.

Here we are in China in the 1970s, but rather than seeing the destruction and privation of the Cultural Revolution, we find ourselves in a hyper-technologized space, a radar station that can beam signals into outer space. The Chinese show explicitly foregrounds technological accomplishment, both in the past and in the present.

There are two narrative strands, one following Ye Wenjie’s life and work at the Red Coast base, and one following a team of investigators trying to figure out why prominent physicists have been committing suicide in 2008.

Ye’s workplace may not be state of the art for the 1970s, but as her supervisor points out, it is a stunning testament to the remarkable scientific progress that China has made despite its alienation from the Western world and, following the 1960 Sino-Soviet split, from the USSR.

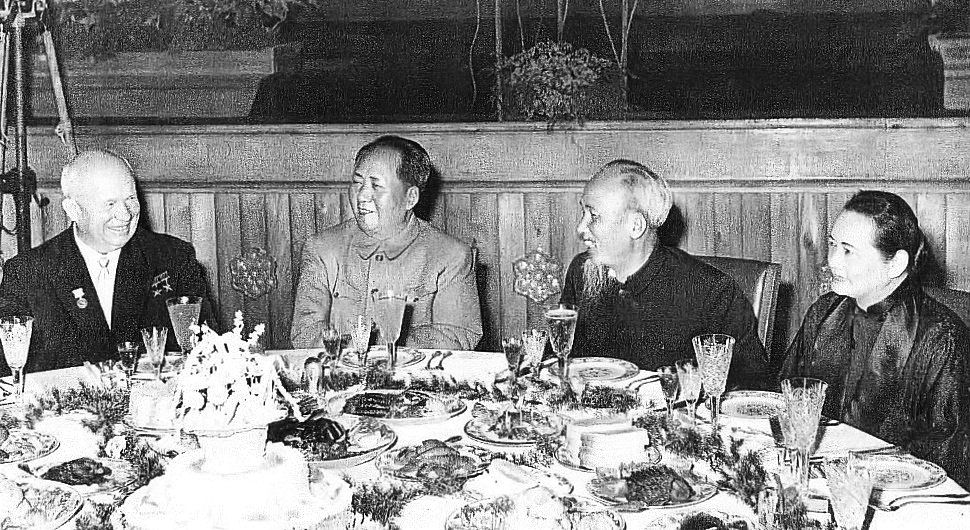

In reading or watching Three Body, it is important to understand the geopolitical and technological context in which the series unfolds. The Cold War is generally understood as bipolar conflict, but this framing obscures the fact that by 1960, the USSR and China had significantly different geopolitical commitments.

The Sino-Soviet alliance, initially a crucial partnership that allowed China to develop its economy, technology, and infrastructure with the help of Soviet advisors, became strained when Nikita Khruschev condemned the excesses of Stalinism in 1956.

In the same period, the Chinese communist party seemed open to ideas about reform. The Hundred Flowers Movement, independently conceived but launched shortly after Khruschev’s speech, was a political campaign aimed at soliciting constructive criticism.

The unexpected popular dissatisfaction that it revealed shocked the country’s leadership and led to the oppressive Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957. Dissenting opinions were harshly prosecuted and even committed leftists ran the risk of being labeled rightist.

While the repercussions of Khruschev’s speech were mitigated in Eastern Europe (which also experienced political unrest in the mid-1950s), they laid the ground for a dramatic break between the USSR and China.

A series of escalating slights led to the withdrawal of Russian advisors from China in the early 1960s. At merely 10 years old, the PRC had lost its most important ally. The PRC’s relationship with the USSR became a rivalry that played out internationally. Each nation claimed moral authority as a developmental leader in the so-called Third World.

Interestingly, the US adaptation of Three Body points to this global context as well. Meticulous in its historically accurate set design, the show’s opening sequence features multiple banners and posters. The bottom of the stage reads: “Overthrow Socialist Imperialism,” a statement that at first glance appears out of place.

The proper historical context, however, shows that Ye’s Cultural Revolution murder is carried out literally on top of an ideological foundation rooted in the Cold War. “Socialist Imperialism” refers to the USSR’s developmental programs and its Third World diplomacy, policies decried by a Chinese foreign policy establishment vying with the USSR for influence in the developing world.

By fetishizing historical accuracy at the level of set design but failing to properly contextualize the complex logic of Cultural Revolution politics, the American adaptation presents a shallower representation of a complex geopolitical and historical reality.

As Covell Myskens explains in his book, Mao’s Third Front, China’s break with the USSR also led to anxiety at home. The United States surrounded China with military bases throughout East and Southeast Asia.

Mao’s power had been diminished after his developmental program, the Great Leap Forward (1957-1960), failed disastrously. He advocated for a developmental program that would relocate Chinese industrial production inland for protection in the event of war, but moderates were skeptical.

However, the 1963 US bombing of Northern Vietnam led the Chinese leaders to suspect an “impending” Sino-US conflict. The militarized development program known as the Third Front was thus launched as a response to China’s fragile geopolitical position.

Although industrialization of the interior was ultimately only minimally successful, and the program was ultimately abandoned in the 1970s, the Third Front mobilized millions of workers to construct a “secret military industrial complex” that would allow China to succeed in a potential Cold War contest (against either the US or USSR).

Red Coast, the military installation that allows Ye Wenjie to communicate with extraterrestrial invaders, is not identified specifically as a Third Front facility. Mysterious, closely guarded, and located in a remote Inner Mongolian region, it certainly fits the Cold War atmosphere of the Third Front and should certainly be understood as a part of China’s Cold War infrastructure.

Thus, the tragic vagaries of the Cultural Revolution certainly led Ye to her radical plan, but she would not have been able to execute it outside of a Cold War context.

American and Chinese Views: Cold War and Cultural Revolution in Three Body

Viewers should not forget the Cultural Revolution and solely embrace the Cold War framework as accurate.

The original book’s author certainly intended to frame it in terms of the Cultural Revolution, but such work is not politically permissible in contemporary Chinese cultural production. The American program is not similarly constrained and can refocus the narrative on the Cultural Revolution and the betrayal of Ye Wenjie’s humanity.

Many Chinese fans of Three Body critiqued the American adaptation of the novel, wherein China causes a catastrophe and a motley crew of Western scientists saves the world.

Writing in the New York Times, Li Yuan notes: “The reactions show how years of censorship and indoctrination have shaped the public perspectives of China’s relations with the outside world. They don’t take pride where it’s due and take offense too easily. They also take entertainment too seriously and history and politics too lightly. The years of Chinese censorship have also muted the people’s grasp of what happened in the Cultural Revolution.”

Li’s suspicion of Chinese reactions conforms to a reading of the program articulated through the Cultural Revolution. But I am not sure that “history and politics” are necessarily taken too lightly by those who critique a narrative that, in its American adaptation, sees Western heroes rescue the world from a disaster unleashed by Chinese radicalism.

The US series and Liu’s original share an opening sequence that harrowingly illustrates the Cultural Revolution, but Liu creates Chinese characters who work in coalition with the rest of the world to resolve the crisis.

The Chinese TV adaptation too shows China as a global leader working to prevent catastrophe. It posits China as a science and technology superpower embroiled in a war against an absolute enemy.

It’s not surprising, then, that Liu’s science fiction oeuvre has inspired a cadre of technonationalists who privilege technology as a means of attaining power and ensuring China’s supremacy in a conflict-ridden future.

This technonationalist fervor is, of course, problematic, but it also shows the relevance of Liu’s oeuvre to contemporary geopolitics.

The author himself is wary of geopolitical interpretations of his work. Yet his novels undoubtedly have undergone Chinese cultural production that may not have been commissioned by the state, but nevertheless supports political narratives of China as a powerful technological actor.

Liu’s reception in the United States sees his work squarely in this New Cold War paradigm, as in a 2019 New Yorker piece that interprets his writings in contemporary geopolitical terms.

Three Body is not just a symptom of the New Cold War that we might diagnose in terms of “brainwashing.” It’s already a story about the Cold War (even if Western viewers overlook that), and it deserves consideration as such if we are to understand how the past unfolds within the new conflict.

Cumings, Bruce. The Korean War: A History. Modern Library Edition: 2010.

Kwon, Heonik. The Other Cold War. Columbia University Press: 2010.

Meyskens, Covell. Mao’s Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Von Eschen, Penny. Paradoxes of Nostalgia: Cold War Triumphalism and Global Disorder since 1989. Duke University Press: 2022.

Weisberger, Joseph. Russia Upside Down: An Exit Strategy for the Second Cold War. PublicAffairs: 2021.