In her book, Health, Healing and Illness in African History, Rebekah Lee explores the rich medical history of Africa stretching from the precolonial and colonial periods to the present day.

This broad survey examines a wide array of chronic diseases found on the continent such as malaria and sleeping sickness, the Spanish Influenza, cholera, bubonic plague, HIV/AIDS, syphilis, leprosy, ebola as well as occupational diseases including tuberculosis, silicosis and asbestosis.

However, the focus of the book is not merely on diseases but also on how a cast of actors, including African patients themselves, families, communities, traditional healers, healthcare workers, and national and international health organizations understood and managed these illnesses. As Lee states, "The chronological sweep and broad geographic reach of this book allow for a consideration of larger dynamics and patterns over time and space."

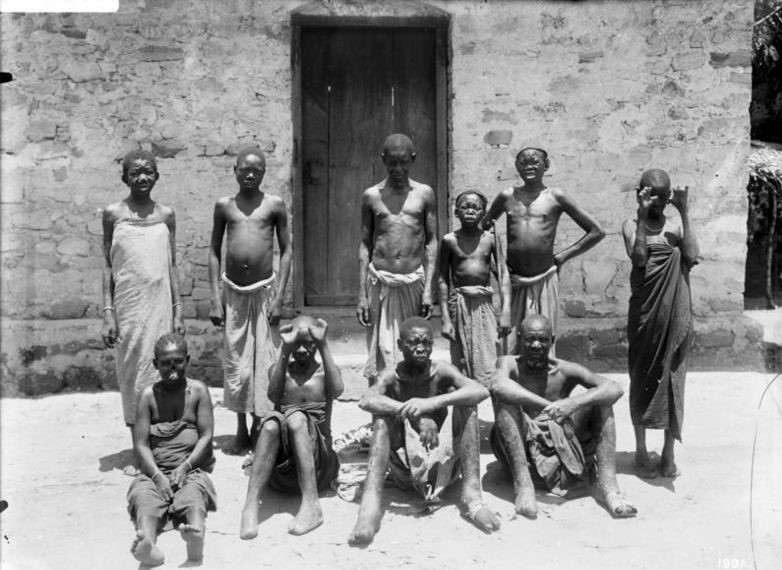

The book is divided into two parts. The first section is organized chronologically. In chapter one, Lee takes the reader back to Africa’s precolonial past to explore a broad range of epidemics such as malaria, leprosy, sleeping sickness, syphilis and dysentery, and the early healing systems deployed to curb disease prevalence.

To reconstruct this precolonial disease history, Lee consulted an array of rich primary sources including archaeological artifacts, linguistic archaeology, oral traditions, Arabic accounts, Portuguese travelogues, Islamic legal records, and Christian missionary accounts.

Paitents at the Bagamoyo Leprosy Home in Tanzania, circa 1906.

Chapter two describes the disease challenges that Africans encountered during the colonial era. Lee notes that certain disease outbreaks coincided with the onset of colonial rule, such as sleeping sickness epidemics in 1890 and 1910 in Uganda, Tanganyika and Nigeria.

Conflicts and contestations arose between African traditional healers and the colonial healthcare providers over causation and therapeutic approaches to combat particular diseases. Coercive and racialized health interventions also characterized the colonial period, with sanitary segregation measures and criminalization of venereal diseases imposed on Africans.

Chapter three examines interventions by the African states in the post-colonial period. It explores the resurgence of old diseases such as malaria, cholera, smallpox, and sleeping sickness and the resurfacing of traditional healing therapies. Traditional healers’ associations suppressed and segregated during the colonial period were now recognized, as evidenced by the reformation of the Association of Traditional Healers in Ghana in 1963. During the battle against HIV/AIDS traditional healers were given fundamental roles to play by the World Health Organization.

A traditional healer in Namibia, 2014.

The second part of the book examines a set of four disease case studies: HIV/AIDS, mental illness, tropical diseases and occupational lung diseases. Chapter four looks at HIV/AIDS. This disease had and continues to have a profound demographic impact on African countries, especially South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Lesotho. These places have the highest mortality and morbidity rates on the continent and among the highest across the across the globe.

In chapter five, Lee examines African mental illness in a historical context, something that has generally been neglected by previous scholars. This chapter may be the weakest in the book given just how difficult it is to find historical evidence. Chapter six examines the history of two classic tropical epidemics, namely malaria and sleeping sickness. Lee thoroughly examines their resurgence and deadliness over time and space.

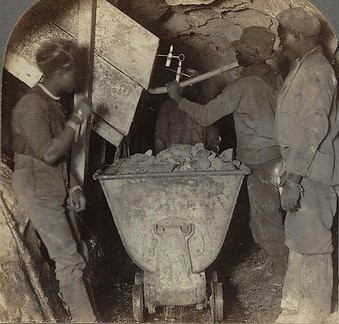

The final chapter deals with occupational lung diseases: tuberculosis, silicosis and asbestosis in apartheid South Africa. These ailments were categorized into communicable (tuberculosis) and non-communicable diseases (silicosis and asbestosis). Lee’s examination of how these sicknesses were racialized in the apartheid era is particularly interesting.

For example, silicosis was regarded as a "white death" while tuberculosis was deemed an African man’s disease. Although the geographical focal point of this chapter is South Africa, the author presents much broader implications since immigrants working in South African mines were drawn from surrounding southern African countries.

This chapter may be the book’s most significant contribution to the medical history of Africa because these illnesses have largely been ignored by historians. As Lee points out, “—apart from a handful of fairly recent disease-specific studies…occupational lung disease is hidden from the medical history of Africa.”

One strength of this fascinating medical history of Africa is its interdisciplinary approach. It draws on work on history, anthropology, archaeology, ethnography, linguistics and medicine to reconstruct the story of how Africans faced health challenges across a wide sweep of time. Lee has also made effective use of primary source materials and provides a useful set of additional readings for those who want to explore these topics further.

This is an important book for historians and social scientists of Africa and while it was undoubtedly begun before the global COVID-19 pandemic, it seems even more relevant now.

This content is made possible, in part, by Ohio Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this content do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.