For over forty years, John Murrin has been among the most influential historians of colonial America, the American Revolution, and the Early American Republic. This compilation gathers together some of his important essays published or delivered between 1973 and 2007. While the collection is retrospective, Remaking America is an incredibly useful resource for understanding how historians have approached the field and how those approaches have changed.

The eleven essays reflect Murrin’s contributions to key themes of early American historiography, including the concept of colonial “Anglicization,” the problems of historiographical isolation, the need for transatlantic approaches to American history, and longue durée history.

Arguably, Murrin’s greatest scholarly contribution is his discussion of “Anglicization.” Rather than becoming less and less British as the 17th and 18th centuries wore on, Murrin believes American colonists became more and more like the compatriots they left behind.

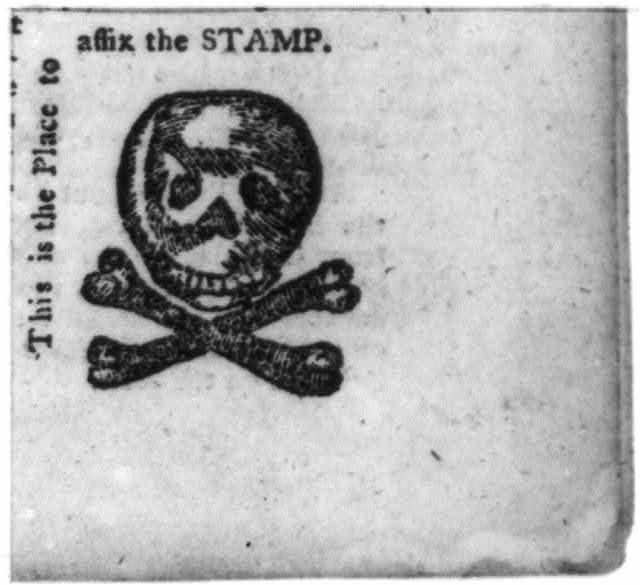

Although diverse groups settled in the colonies during the 17th century to escape England’s political and religious crises, the kingdom’s stabilization in the 18th century attracted colonists who sought to emulate their British counterparts in all aspects of their lives. By the 1760s, Murrin argues, they were more British than ever and the tensions that arose during that decade were caused by the colonists who viewed themselves as equal to their fellow Englishmen and believed Parliament was not treating them as such.

Anglicization was not just a matter of economics and politics, but also of social class. Colonial elites of the 18th century believed they were more akin to British gentry than to lower class colonists. In light of the growing fracture between London and its colonies, however, the elites reached out to the lower classes to fight for a singular cause, using ideology to explain how Great Britain had wronged them and to persuade them to support their interests. The initiative afforded colonial elites the revolutionary support they desired, but this strategy later backfired when the lower classes used the same ideology to challenge the elites, as in the election of 1800.

It may be that the origins of the War of Independence lie somewhere between Murrin’s ideas and the idea that the development of colonial autonomy made colonists increasingly hostile to the British parliament. Surely, the creation of colonial legislatures made colonists wary of Parliament: they began to prefer their own means of governance.

Yet it is also true, as Murrin demonstrates, that as the colonists became more “British,” they increasingly attached themselves to the royal executive as the monarchy developed into a stable, Protestant, constitutional one.

In the final analysis, Murrin argues that the clearest understanding of history comes when we consider fragments as a whole. This can only be done by making connections between various historiographical approaches. Different schools of thought should engage with each other rather than rebuffing one another. Put another way, since 18th-century subjects did not distinguish constitutional/ideological from material/economic, neither should historians try to separate such spheres. Because Murrin examines so many elements at once, individual arguments sometimes lack satisfactory explanation, but such is the nature of such a vast enterprise.

Murrin makes good on this by taking a transatlantic approach to colonial history, arguing that understanding the workings of the British empire helps us to comprehend colonial fracture and vice versa. This transatlantic approach allows historians to contemplate everything from the effects of the English Civil War to the causes of the American Civil War. Murrin suggests that the American Revolution cannot be treated as a breaking point or solitary event, for historians need to study it in conjunction with the colonization of America and republican experimentation in England.

Given that the majority of contributions are over twenty-five years old, there are occasional pieces of outdated interpretation. In the end, though, as Murrin writes at the beginning of the book, the goal of this collection is to “address essential questions and controversies that have long shaped our understanding of the nation’s origins and that should continue to inform the discussions of current and future historians.”

To that end, Rethinking America does not disappoint. Through Murrin’s deep and thoughtful analyses, these essays challenge historians to continue rethinking early America in order to better understand their time and our own.