Driving a colleague to the airport this Thanksgiving break, I took advantage of my captive audience to rehearse the impressions I was forming of the book which is the subject of this review: Jack David Eller’s Inventing American Tradition: From the Mayflower to Cinco de Mayo.

I derived great pleasure, I explained, from Eller’s mythbusting. He shows that the first Thanksgiving was little more than a harvest festival, and that the morally conservative Puritans would have eschewed the indulgence and recreation that characterizes the holiday today. In fact, Thanksgiving really traces its modern origins back to the Civil War, not to the colonial period. Both the Union and the Confederacy made Thanksgiving proclamations during the war and in 1865 Andrew Johnson institutionalized it as a tradition. Revelations like these are the best parts of the book.

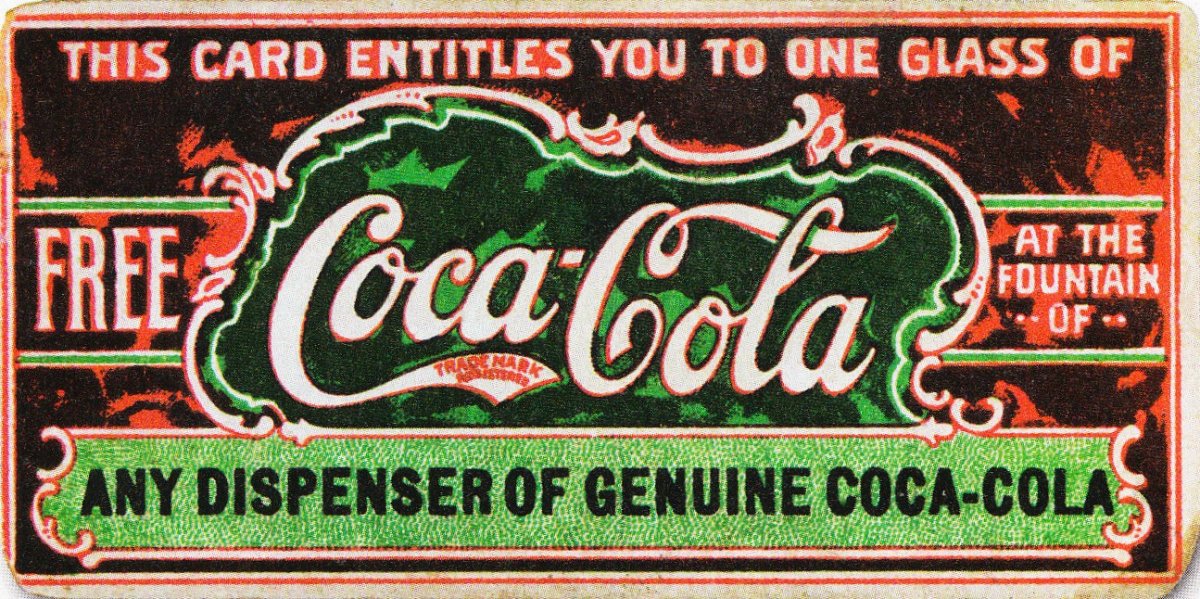

Each of Eller’s fifteen chapters offers a survey of the given tradition’s popular history, identifies some of the myths surrounding it, and debunks them. He groups them into four parts: “American Political Traditions” (in which he discusses the National Anthem, the flag, Uncle Sam, the Pledge of Allegiance and the motto); “American Holiday Traditions” (Thanksgiving, parental holidays, patriotic holidays, and ethnic holidays); “American Lifestyle Traditions” (“OK,” Coca-Cola, the hamburger, blue jeans); and “American Traditional Characters” (Superman, Mickey Mouse, Rudolph and others).

Readers will learn about Memorial Day’s origin as a Southern celebration of Confederate veterans, only later to be co-opted by Northerners, and that Flag Day exists partially because of the lobbying of the right-wing Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, which barred members of unions from membership because they were “unpatriotic.” And Eller reveals that Mother’s Day was originally conceived of as a pacifist holiday, though Woodrow Wilson popularized it as a jingoistic celebration of the flag.

Perhaps the most compelling stories Eller tells come in the political and holiday tradition sections of the book. They remind us of just how profound the impact of the Civil War has been on American culture. For example, during the war and the years that followed, flag protection movements coalesced, amplifying growing calls for a “Pledge of Allegiance.” Soon after, Thanksgiving and Memorial Day would gain official recognition.

At the same time, the book will frustrate those looking for a more thorough historical study of the traditions Eller considers. Perhaps that criticism is unfair since Eller is an anthropologist. Still, the book does not get off on the right foot. It begins with a daunting thirty-five page introduction, steeped in turbid anthropological theory. Eller himself even suggests in the preface that readers may skip the introduction if they do not wish to “engage in the scholarly analysis of tradition.” Skip it.

Further, he acknowledges that the book’s chapters may be read in any order and this underscores that there is no narrative thread to follow, nor argument offered, save for the thematic sequencing of the book’s four sections. Nor is there any serious engagement with primary source research; the book is really a synthesis of secondary material.

In very few places does Eller interrogate the myths of American tradition. Rather, he simply offers them as they are (or, as he sees them) while ignoring the greater implications of America’s seemingly benign traditions. While he certainly discusses American traditions he doesn’t say much about them: his mosaic of historical trivia comprises an explication but not an argument.

Return to the Thanksgiving table for a moment. Eller barely engages the Native American element of Thanksgiving mythology. He devotes only a paragraph-and-a-half out of the 20-page chapter to Native American responses to Thanksgiving, noting that they hold it as a National Day of Mourning. But Native American challenges to the traditions of Thanksgiving (and Columbus Day), have been documented by historians, and their absence here means that Eller’s hasn’t really given us a complete picture of this American tradition.

Inventing American Tradition plays with the title of a collection of essays edited by Eric Hobsbawm and T. O. Ranger titled Invented Traditions. That book has become a classic for historians. This one is filled with fascinating tidbits of American folklore but unfortunately it does not cohere into a larger historical picture.