The world is awash in nationalism and India, the world's largest democracy, is no exception. Sometimes pundits have called this politics "populist," others have called it racially or ethnically driven. In India, as historian Archana Venkatesh explains, the roots of nationalists’ politics are religious, and those roots run deep. This month she explains the long history of the Hindu nationalism we see triumphant in Indian politics today.

In April and May 2019, the world’s largest democracy held elections. More than 540 million voters, out of 900 million registered, cast ballots. The global press portrayed the election as a contest between the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress, though India is a multi-party parliamentary democracy. The BJP won an overwhelming majority and returned to power in Parliament.

The results of the election have sparked a wide-ranging discussion about the rise of right-wing, religiously rooted nationalism in India. Since its creation in 1947, India has been a Hindu-majority country. The 2011 census revealed that nearly 80% of the country’s population are Hindus (more than 1 billion people), with Muslims comprising the next most populous group at 15%.

First-time voters in India’s 2009 General Election.

This demographic breakdown is important. Critics of the BJP have noted that the party based its campaign around a rhetoric of “Hindutva” or Hindu nationalism. The BJP popularized an ethnically divisive discourse in order to gain Hindu votes and create a culture of majoritarianism that would exclude minority communities in India.

This is not the first time the BJP has won an election on a campaign emphasizing Hindu nationalist feeling. But it is the first time it has obtained an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha (“House of the People,” the lower house of India’s bicameral Parliament), enabling it to govern without forming a multi-party coalition.

The term “Hindutva” has come to describe a political ideology that insists India is a Hindu nation (rather than a secular one, as the Indian Constitution defines it). While the party has come to embody this ideology, the roots of Hindutva lie in the late colonial period.

Although occupying a marginal place on India’s political spectrum for most of the 20th century, the discourse of Hindutva emerged at the forefront of Indian politics through a series of incidents. Over more than a century, Hindutva adapted to the anti-colonial national movement and post-independence secularist governance in India.

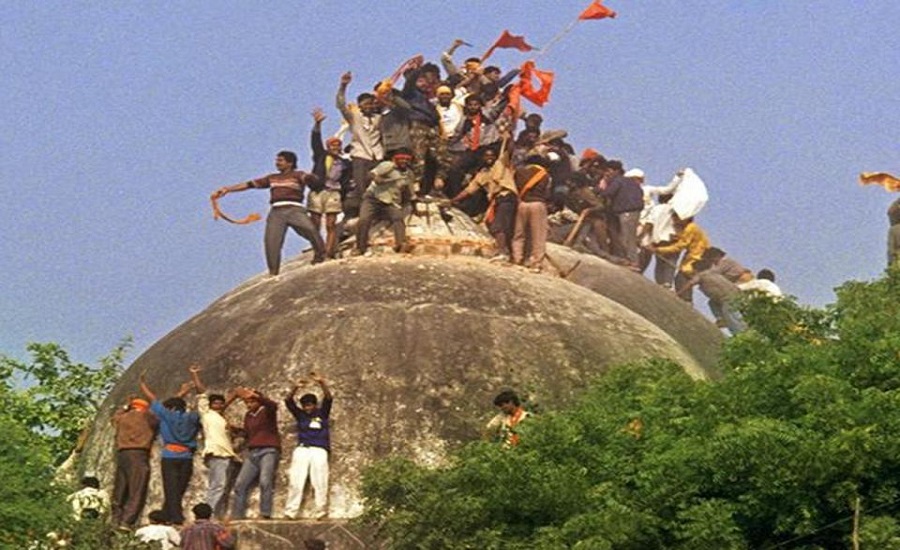

Hindu nationalists in 2015 commemorate the destruction of the Babri Masjid.

An anti-Muslim stance was central to this process. Recent events in the state of Jammu and Kashmir have made it clear that Hindutva is premised on the belief that Muslims are not inherently citizens of India.

It is worth noting that while the BJP has ridden a Hindu-nationalist platform to power, it employed other electoral strategies as well. Its economic development-driven agendas appealed to a wide cross section of groups, including Hindu women, over the past 20 years.

Nationalism and the Roots of Hindu Majoritarianism

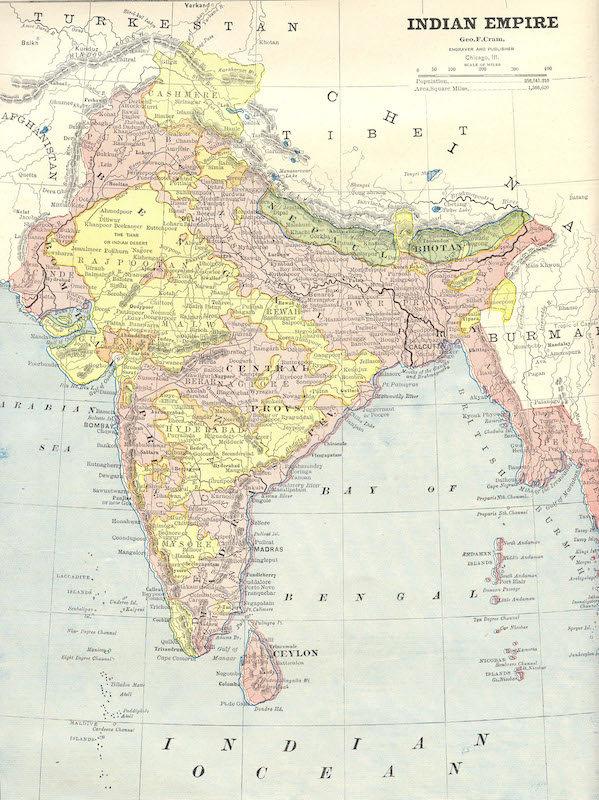

George F. Cram 1885 map of India during British Raj.

Nationalist sentiment against British colonial control in India coalesced with the formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885. For many years, the Congress was comprised of elite male Indian lawyers and doctors educated in the western style, often in the United Kingdom. They met regularly to air their grievances against the British Raj, and to create petitions for increased participation for Indians in governance.

As anti-colonial nationalist thought morphed from demanding reform to demanding independence from British rule in the 1920s, the Congress began to position itself as the leading organization in the movement for Indian independence from British rule. In doing so, it sought to present itself as an inclusive, secular-nationalist body that represented the interests of all Indian people—including all religious, linguistic, and caste groups.

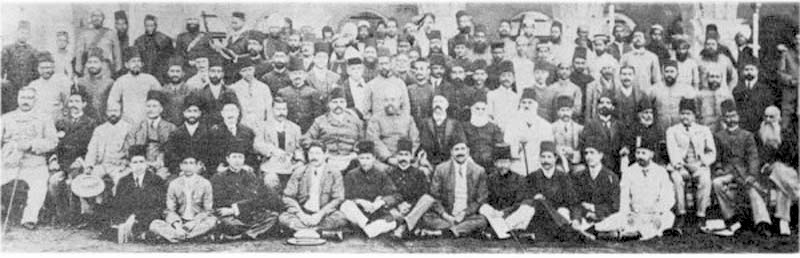

The first session of the Indian National Congress met in December 1885 in Bombay.

Despite their claims of inclusiveness, the Congress often failed to adequately represent the interests of minority communities, alienating lower-caste leaders such as Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, anti-caste radicals such as E. V. Ramasamy in Madras, and a number of Muslim leaders who went on to form the Muslim League in 1906.

During the 1930s, in the final push to independence, the Muslim League and the Congress found themselves increasingly at loggerheads and unable to find common ground. By the 1940s, the British were keen to pull out of India as quickly as possible with little interest in resolving the communal differences colonialism had fostered. The timeline for Indian independence was reduced from an initial plan of 18 months to 6 months.

The All India Muhammadan Educational Conference in 1906 led to the creation of the Muslim League.

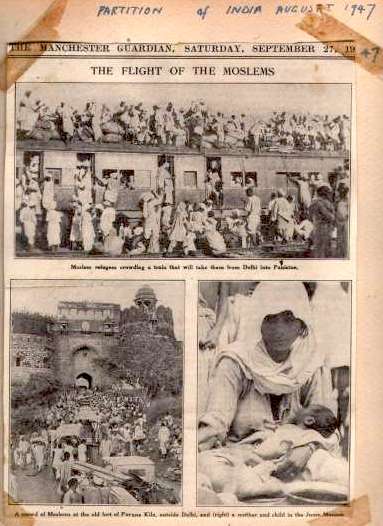

The resulting confusion over borders was accompanied by increased religious violence and mass migration of Hindus from Pakistan to India, and of Muslims from India to Pakistan. Instead of the joyous freedom they had hoped for, peoples of the Indian subcontinent spent August 15, 1947 in the horror of Partition, bloodshed, and brutality.

The Congress’ stated commitment to inclusivity and secularism also came under fire from a closer quarter: those Hindus who felt their interests were being sidelined in order to appease minority groups. These critics expressed discontent with Congress-style nationalism in the Hindu Mahasabha, an organization formed in 1906 to serve as a counterpart to the Muslim League. They wanted to unify Indian Hindus across caste and community divisions.

Hinduism itself, however, was hardly monolithic. A 1911 census noted that “a quarter of the persons classed as Hindus deny the supremacy of Brahmans, a quarter do not worship the great Hindu gods … a half do not regard cremation as obligatory, and two-fifths eat beef.”

The leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha believed it was their duty to create a community of people who identified themselves as Hindus first, rather than by caste, community, or linguistic affiliations.

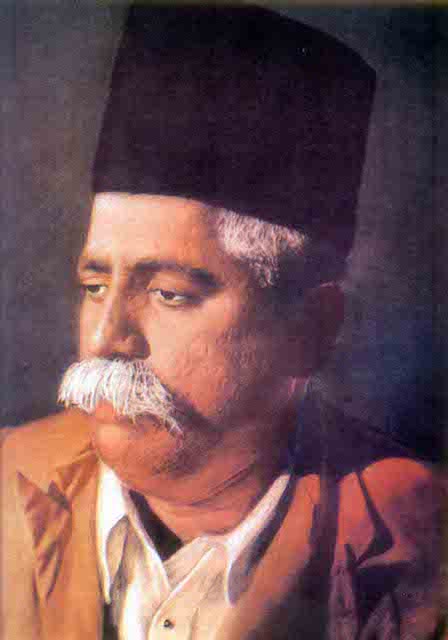

Dr. K.B. Hedgewar established the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in 1925.

Though they were on the fringe of politics, the Hindu Mahasabha was the first organization established with the explicit goal of promoting Hindu interests and an implicit concern about possible preferential treatment of minority groups, especially Muslims. One of its members, Dr. K. B. Hedgewar, established the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (the National Volunteer Organization, or RSS) in 1925.

The Rise of Hindutva as a Political Philosophy

Hedgewar believed India was a Hindu nation that had been exploited at a time of weakness and conquered by successive Islamic dynasties (the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals) and finally the British Empire. Impatient with the strategy of passive resistance to the British Raj introduced by M. K. Gandhi from 1917-1920, Hedgewar believed that the only way to throw off the yoke of colonial rule was through more aggressive activities. He found his inspiration in the work of V. D. Savarkar.

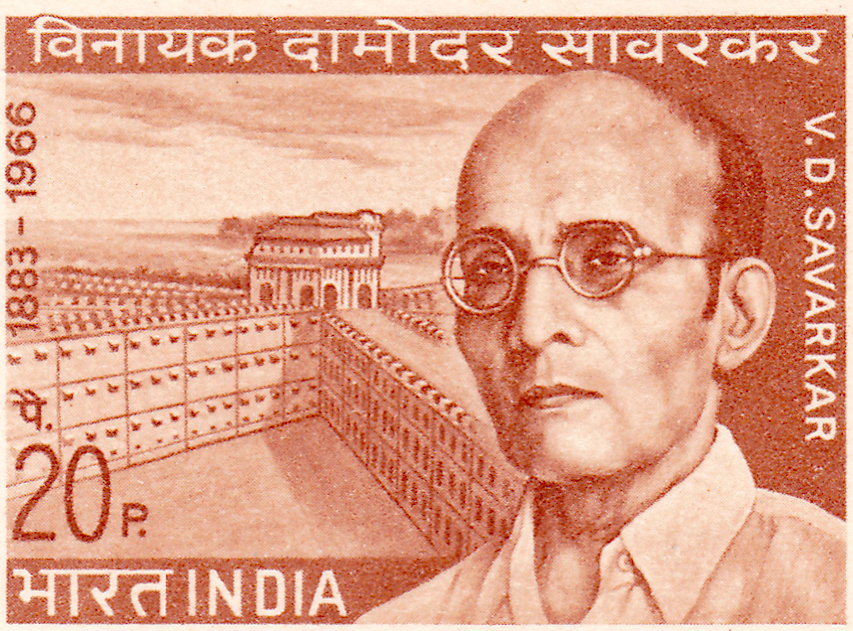

A 1970 Indian commemorative stamp of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

During his studies in London and work with various revolutionary groups in India, Savarkar concluded the British were able to colonize India because of a lack of masculine strength among the Hindu people. Savarkar painted the previous Islamic rulers as colonizers like the British.

Muslim interests in India, he argued, were about dominating Hindus. In particular, Savarkar believed that “no realist can be blind to the probability that the extraterritorial designs and the secret urge goading on the Moslems to transform India into a Moslem state may at any time confront the Hindustani state even under self-government either with a Civil War or treacherous overtures to alien invaders by the Moslems.”

Dr. Hedgewar (front row, second from the left) in 1939 with five other original RSS members.

Hedgewar also admired the work of Benito Mussolini and the Fascist party in Italy, noting their efficiency and seeming success in unifying a divided nation. Impressed by Savarkar’s political vision of Hinduism as the basis of nation-building, as well as the efficiency of fascist parties in Europe, Hedgewar found a way to bring these together in the creation of the RSS in 1925.

The RSS recruited young men, trained them in combat using swords and lathis (sticks or truncheons), and clothed them in brown shorts and uniforms. His aim was to give male Hindu youth a sense of pride in their religious customs and national past—which he portrayed as one and the same.

Today, the RSS is widely acknowledged to be the militant wing of the “Sangh Parivar” (family of organizations) that comprises a number of political and paramilitary parties in India. Nearly all leaders of the BJP (the political wing of the Sangh Parivar) are former members of the RSS.

Hindutva’s Vision of Independent India

Hedgewar’s disdain for the Congress party meant that the RSS participation in the freedom movement in India was lukewarm at first. And it ceased altogether as British policy began to ban political parties that advocated militancy rather than the noncooperation, passive resistance, and civil disobedience made popular by Gandhi and the Congress. By the time of the Second World War, as the independence movement went into high gear, Hedgewar turned over leadership of the RSS to his protégée, M. S. Golwalkar, in 1940.

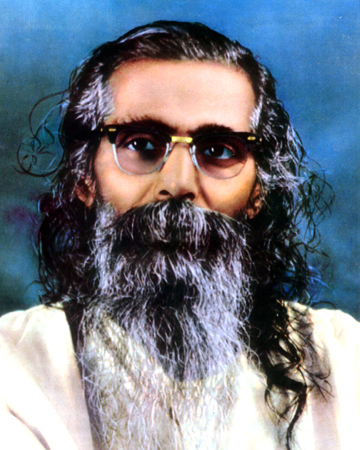

Second Supreme Leader of RSS, Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, died in 1973.

Golwalkar embraced the RSS ideology wholeheartedly, believing that India should be a Hindu state and that militancy was the best way to achieve that goal. He promoted idealized versions of former Hindu kings, such as Shivaji, as enlightened rulers in contrast to the Mughal “oppressors” of India.

The RSS leadership had long felt that repeated invasions and colonization were symptoms of a larger social malaise: the weakness of Hindu masculinity and the inability of Hindus to defend themselves from “foreigners.” As he rose through the ranks of the RSS, Golwalkar saw Adolf Hitler in much the same light as Hedgewar saw Mussolini: a man who gave his countrymen their pride and strength back.

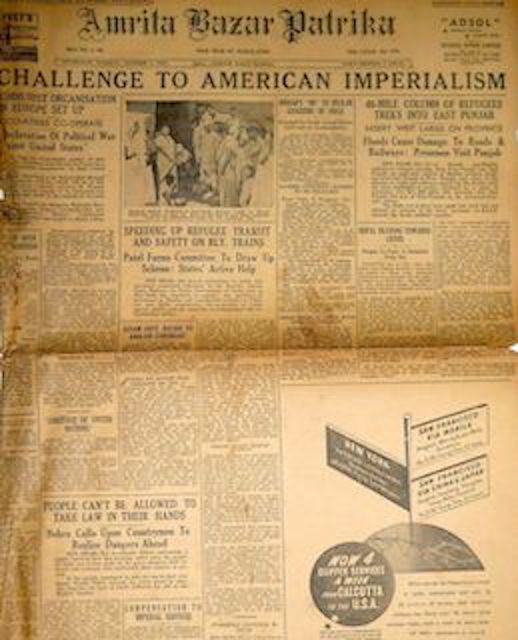

October 7, 1947 edition of Amrita Bazar Patrika, an anti-colonial newspaper in Bengal, India.

Golwalkar’s vision for India was more nuanced than Hedgewar’s in some ways. They agreed that taking an anti-British stance would endanger the existence of the RSS as the 1930s, in particular, were tumultuous in India. The British banned many political organizations and shut down a number of anti-colonial newspapers. Golwalkar also believed that British rule was not an obstacle to achieving a Hindu nation; rather Muslims stood in the way, along with Christians and communists.

Rather than challenging the British directly and putting the organization at risk, Golwalkar focused on building a force that would be strong enough to create and defend a Hindu nation. In order to carry out this agenda, Golwalkar ramped up the paramilitary aspect of RSS training activities.

In 2017, there was no age restriction for joining the RSS.

He reiterated the notion that Hindu men (particularly young men) had to be strong in order to defend their motherland from “outsiders,” something they had failed to do in the past. “It is the forefathers of the Hindu people who shed their blood in defence of the sanctity and integrity of the motherland,” Golwalkar wrote. “Only the Hindu has been living here as a child of this soil.”

In other words, he wanted to make India great again without coming into direct conflict with the British Raj, which might ban his RSS. Subsequent events made it clear that he had a longer vision for India.

Partition and the Question of Kashmir

As the British frantically exited the subcontinent in 1947, they left a region that had hoped for independence and had gotten it—in the form of Partition. The world watched in shock as two nations—India and Pakistan—were born amidst religious and ethnic bloodshed.

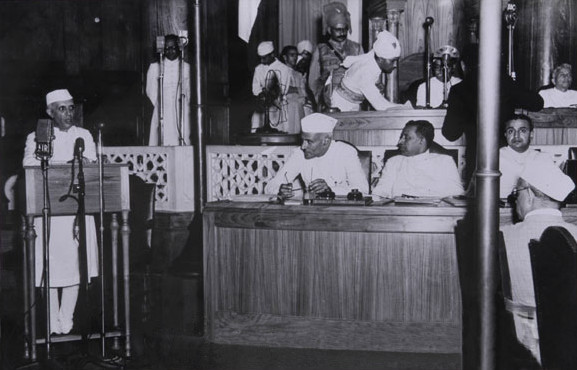

While Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru celebrated the birth of a nation in New Delhi, and as Pakistani Prime Minister M. A. Jinnah’s first speech to the Constituent Assembly stressed the importance of creating a secular ethos in the country, many other leaders were desperately trying to stop the communal violence.

The RSS and Hindu Mahasabha were furious about the Partition.

Savarkar believed that land had been “taken away” from India and given to Muslims. He was also upset that the remaining land in the subcontinent was called “India” rather than “Hindustan” (land of Hindus). His vision for post-colonial India was a united Hindustan, which would include a Muslim minority that was granted no protection from majoritarianism or populism.

The Congress had promoted measures to protect religious minorities in terms of marriage laws, educational institutions, and weighted participation in democracy, in order to create an equitable representation of all Indian communities at the nationalist table.

Savarkar grew increasingly vitriolic in his criticism of these measures. He argued that “the Hindus do not want a change of masters, are not going to struggle and fight and die only to replace an Edward by an Aurangzeb simply because the latter happens to be born within Indian borders, but they want henceforth to be masters themselves in their own house, in their own Land.”

Painting of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb confronting an angry elephant, c.1633.

Golwalkar was equally angry, as evident in his reaction to the drafts of the Indian Constitution. He believed it should have been written on the basis of ancient Hindu law rather than a “foreign” approach based on human rights.

Like Savarkar, he blamed the “hostility and murderous mood” of Muslim masses in India as the direct cause of the communal riots in 1947, while failing to note that acts of horrific violence, arson, and looting were committed by many religious and political groups in the subcontinent.

Some years later, he went so far as to write, “the naked fact remains that an aggressive Muslim state has been carved out of our own motherland.” Golwalkar suggested that the Indian subcontinent was the homeland of Hindus (“Hindustan”) and that Muslim leaders were constantly conniving to “steal” bits of it.

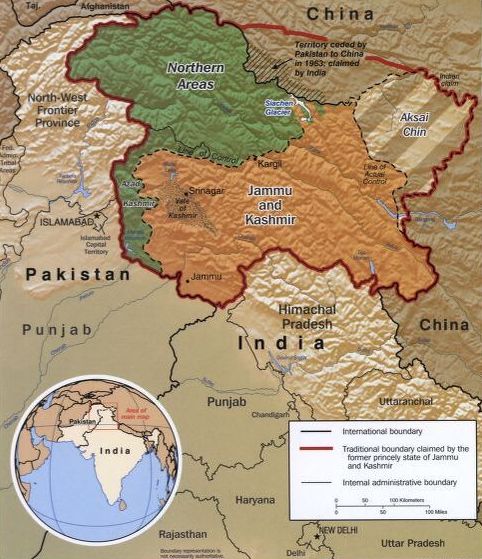

This ideology was clearly expressed when it came to the question of Kashmir.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) map of the Kashmir region in 2003.

Kashmir has long been a major source of tension between India and Pakistan. As soon as the British transfer of power document bifurcated the subcontinent, both countries went to war over who would control Kashmir.

Kashmir was a Muslim-majority Princely state ruled by a Hindu king. At the time of independence, the majority of Princely states signed a document of accession to join either India or Pakistan, but Kashmir’s Maharaja was keen to create an independent state. Pakistani troops invaded Kashmir and the Maharaja was forced to accede to India in order to secure military help.

Maharaja (king) of Jammu and Kashmir, Hari Singh, in 1931.

The urgency of the situation resulted in a somewhat slipshod document of accession. This, combined with the fact that a promised plebiscite was dependent on the withdrawal of Pakistani troops (which never happened), meant that the state of Jammu and Kashmir joined the union of India with the caveat that its residents were granted special protections.

These special protection measures for Jammu and Kashmir incensed the RSS leadership. Golwalkar saw it as a blatant attempt by Pakistan to slowly take over India and convert its citizens to Islam.

Kashmir thus became a focal point for the RSS credo and Hindu nationalists have continued to see the region as a crucial part of India. Letting it fall into the hands of Pakistan, or even those groups who demanded a separate state, would therefore constitute a betrayal of Hindustan.

Kashmiri refugees arrive at the Pakistan border in 1948.

On a more ideological level, granting special protection to Jammu and Kashmir was a clear statement that India was not a “Hindu” nation but a secular one, willing to accommodate the cultural and legal requirements of minority groups in communally fraught regions. This was the antithesis of the RSS doctrine, which demanded that minority groups should “integrate,” i.e., submit to Hindu law.

By 1948, RSS members and leaders reached a fever pitch of anger at what they felt was a loss of national pride and the “appeasement” of minority groups by the toothless Congress party.

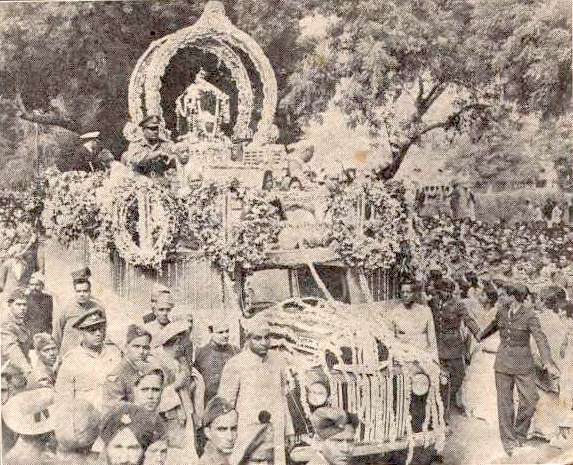

This frustration motivated Nathuram Godse to assassinate Gandhi in January 1948. Godse was a former member of the RSS whose papers revealed that he had been inspired by the words of Golwalkar in particular. Godse believed that Gandhi and the Congress had sold India out by agreeing to partition.

Gandhi’s ashes were carried through the streets of Allahabad in February 1948.

Golwalkar himself was imprisoned for a year on the charge of inciting communal violence and the RSS was banned. After a lengthy inquiry, the RSS was allowed to function again in 1949, with various caveats including the acceptance of the Indian Constitution and the renunciation of violence in agitations and demonstrations.

Because of this ban, the RSS leadership decided that they needed a political party that could participate in parliamentary democracy. This way, the RSS themselves could continue propagating their ideology by flying under the radar without running the risk of being outlawed.

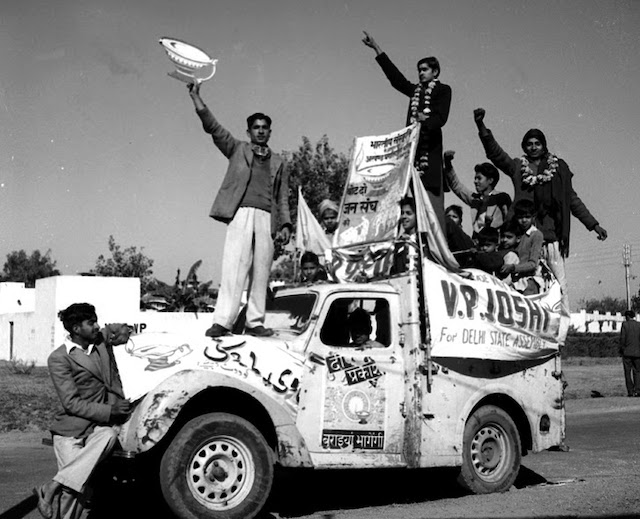

Jana Sangh supporters campaigning in New Delhi in 1952.

To this end, the Jana Sangh (“People’s Organization”) was formed in 1952. The Jana Sangh was the predecessor of the BJP, presenting a Hindutva alternative to the more secular India envisioned by Congress policymaking.

The RSS and the Jana Sangh gained some ground as India remained embroiled in wars against China (with heavy losses in 1962) and Pakistan (1965). The defeat by China allowed them to suggest that Nehru and the Congress lacked the requisite strength to run a nation, while the war against Pakistan allowed right-wing leaders to promote their Islamophobic ideology in mainstream political debates.

1998: Hindutva Captures India’s Imagination (and Votes)

The Jana Sangh enjoyed brief electoral success immediately after the Emergency imposed by Congress Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1975-77, but did not gain much traction until the early 1990s. In 1980, it was rebranded as the BJP. Though still part of the larger Hindutva movement and inspired by the RSS, the BJP was more willing to form coalitions with secular parties.

The BJP mobilized around the issue of the Babri Masjid—a mosque built by the Mughal emperor Babur in Ayodhya (PDF File) (there is some doubt as to who actually commissioned the mosque). Ayodhya was traditionally seen as the birthplace of a Hindu god, Rama.

BJP leaders asserted that the mosque was built by a cruel and oppressive Muslim leader on hallowed Hindu ground simply to spite the Hindus he conquered in 1526. They championed these ideas despite the difficulty of proving an exact location where a semi-mythological figure might have been born nearly 3,000 years ago.

Rioters attack Babri Masjid in 1992.

The issue of the mosque escalated in 1992 when a mob of Hindus led by various right-wing leaders (including some from the BJP) stormed the mosque and demolished it. The implication was clear: Hindus had “taken back” what they considered rightfully theirs through a show of strength. The event caused violent riots in most major cities and exacerbated social tension across India.

The Ayodhya issue demonstrated to the BJP that it could indeed capture the imagination of the upper-caste Hindi-speaking man using the same rhetoric popularized by the RSS decades earlier.

In 1998, by forming a coalition with other political parties, the BJP also captured his vote. India had its first BJP Prime Minister in A.B. Vajpayee; but the RSS considered Vajpayee’s coalition government weak because he was forced to compromise on certain issues.

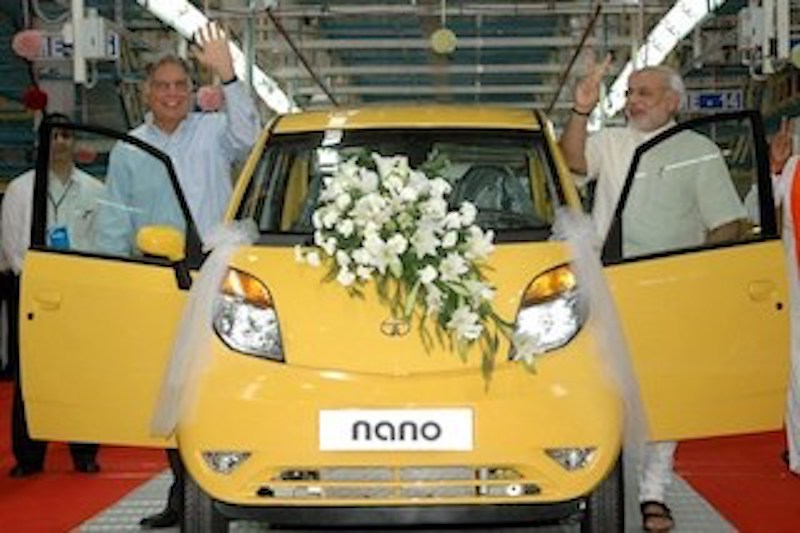

The coalition government was replaced by a Congress-led one in 2004. The RSS needed a new approach to national politics if the BJP was to make progress toward creating “Hindustan.” In particular, it needed to find a way to appeal to Hindu women. It found this new approach in the state of Gujarat, where Narendra Modi was the chief minister and gaining popularity with a development-oriented rhetoric and agenda.

BJP Politics and Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi, like the majority of BJP leaders, was a member of the RSS. He rose to prominence when he won the state election in Gujarat in 2002. Modi’s formula in Gujarat indicated the shifting trends in how the BJP sought to increase its voter base.

He emphasized the notion of development at any cost. In a sense, this was a re-articulation of the early RSS formula couched in neoliberal language. India lagged economically, and the BJP promised to promote developmental measures such as increasing foreign investment to promote Indian industry (which appealed to industrialists and entrepreneurs), electricity for rural India (capturing the votes of farmers), and investments in education, healthcare, and sanitation for girls and women.

In this way, the BJP was able to capture a voter base that had not supported it in the 1998 election—particularly women.

Indian women have participated in elections since voting rights were expanded to include Indians in the late colonial period; universal suffrage was enshrined in the Indian Constitution in 1950. The Indian feminist movement in post-colonial India thus focused on removing other legal disabilities in the 1970s (such as inheritance rights, and protection against domestic violence and workplace sexual harassment), as well as promoting women’s empowerment through access to education and better sanitation.

Female students’ urinals at Govt. Middle School in Tamil Nadu, India, in 2015.

By prominently featuring a campaign to educate Indian girls, the BJP positioned Modi in particular as a paternal figure who would uplift Indian womanhood. Modi also promised to subsidize the construction of toilets in rural India, noting that access to sanitation facilities was important for reasons of hygiene and also women’s safety. Women voters responded to this narrative and began to vote for the BJP in other states as well.

Conspicuously missing from these ambitious plans for Indian development were environmental protections. In addition, rights of those tribes and communities living in forest areas were further eroded. Nevertheless, Modi’s ideas about development appealed to the majority of Indian voters.

This support came despite the fact that his tenure as chief minister of Gujarat was tainted by the horrific 2002 Hindu-Muslim riots in which nearly 2,000 people were killed.

Hindu-Muslim riots in Gujarat, India, in 2002.

While the Supreme Court of India has recently exonerated Modi from direct blame in inciting the riots, most scholars and observers agree that there was gross negligence at best and active complicity at worst on the part of the government in 2002. Some scholars have even described it as an example of “state terrorism.” Modi was denied entry into the United States for many years during the investigation into the riots.

Facing off against a creaking Congress party rocked by corruption and scandal in 2014, the BJP placed Modi at the helm of its national campaign. Given his success in appealing to various voter bases with his promises of development, improved infrastructure, and job creation, the BJP’s rout of the Congress did not come as a surprise.

But in Modi’s first term as prime minister, many of the BJP’s economic goals were not realized and unemployment rates in India went up. In response, the BJP shifted its focus to fighting cross-border terrorism from Pakistan. Once again, Kashmir became the focus of wounded national pride when terrorists killed more than 40 Indian soldiers.

Indian security forces engaged in gun fight in Kulgam, Jammu and Kashmir, in 2017.

Rhetoric around the 2019 election referred more to this insult on India’s honor and less to questions about the failed promises of the 2014 BJP election manifesto. The BJP won a resounding majority in the national elections, forming a government without the aid of coalitions.

Making Hindustan Exist (Again?)

A right-wing Hindutva nationalism in India—a belief that India should be an exclusively Hindu nation—has existed since the dawn of the Indian freedom movement itself. And while the secular Congress party has won more elections in the 20th century, Congress itself has been complicit in fostering the rise of Hindutva, as it often succumbed to majoritarian demands or exerted authoritarian rule in various parts of the country, including Kashmir.

As successive Congress governments were rocked by corruption scandals from the 1970s, it was clear that the party could no longer count on its image as the one that had led the nation to freedom.

When India opened up its markets to the world in 1991, ending an era of limited global trade, development was redefined to rest on increased foreign investment and the rise of multi-national companies. This economic boom led to increased income for the middle classes that had grown restive under the grip of the socialist policies embraced by Nehru and enshrined in the Constitution.

Modi’s 2014 slogan to encourage global corporations to invest and manufacture products in India.

As the BJP rebranded itself to be more “development oriented,” the party was able to capture the imagination of middle-class India by promising foreign investment and “ease of doing business” at the cost of the environment.

The adaptability of the RSS to economic, political, and social changes through the 20th century ensured that its vision of Hindustan is on the cusp of becoming a reality.

BJP rally in Uttar Pradesh in 2014.

At the time of writing this article, Jammu and Kashmir have been stripped of protections and statehood, and part of the region is under a communications blackout. Even as there is little information about how Kashmiris feel about this move, the majority of Indians outside the region have hailed recent events as a means to bring the region development and prosperity and to forward the goals of Hindutva.

Read and Listen more on India and Pakistan: The Politics of India; India-Pakistan Partition; The Debate over Indian Population; Pakistani Politics; The Amritsar Massacre; The British Raj; and South Asia Since Partition

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan or Partition of India. [2d Ed.] ed. Bombay: Thacker, 1945.

Calamur, Krishnadev. “Modi’s Kashmir Decision Is The Latest Step In Undoing Nehru’s Vision.” The Atlantic. Last modified August 5, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/08/india-moves-revoke-special-status-kashmir/595510

Das, Veena. Mirrors of Violence: Communities, Riots, and Survivors in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Geetha, Varadarajan, and International Development Research Centre (Canada). Undoing Impunity : Speech After Sexual Violence. Zubaan Series on Sexual Violence and Impunity in South Asia. New Delhi: Zubaan, 2016.

Jaffrelot, Christophe. “Hindu Nationalism and Democracy.” In Transforming India: Social and Political Dynamics of Democracy, edited by Francine R. Frankel, et al., 353-378. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Nandy, Ashis. "The Politics of Secularism and the Recovery of Religious Tolerance." Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 13, no. 2 (1988): 177-94.

Nigam, Aditya. "Winds of Change: Rise of the Bjp and Challenge of an Alternative." Economic and Political Weekly 48, no. 52 (2013): 37-40.

Palshikar, Suhas. "Majoritarian Middle Ground?" Economic and Political Weekly 39, no. 51 (2004): 5426-5430.

Pillai, Manu S. The Courtesan, The Mahatma, and the Italian Brahmin: Tales From Indian History. Chennai: Westland Publications Private Limited, 2019.

Singer, Wendy. Independent India, 1947-2000. 1st ed. Seminar Studies in History. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 2012.