As national governments and the global scientific community struggle to contain the spread of the coronavirus, they have also spent the last few months confronting a different type of outbreak.

Misinformation about the current public health crisis—which has either denied the existence of the virus entirely or framed it as an intentional product—has proliferated at an alarming rate. It has also enjoyed the most mainstream attention of any conspiracy theory since the 9/11 truther movement.

A 2020 ad for the upcoming Plandemic documentary

U.S. government officials—including President Donald Trump—for weeks pushed the unsubstantiated claim that the virus originated in a Chinese laboratory. A trend called #FilmYourHospital encouraged people to spread pictures of hospital waiting rooms (deliberately emptied as a safety measure) to bolster their belief that the virus is a hoax.

Others watched and shared the “Plandemic” video, which garnered close to 10 million views before social media platforms removed it for violating misinformation policies. According to the film, a cadre of political and scientific elites and institutional bodies—among them Bill Gates, Anthony Fauci, CDC director Robert Redfield, the FDA, and the WHO—created the virus in coordination with a Wuhan laboratory, hoping to infect the world and reap enormous profits from a mandatory vaccine.

While such stories are representative of our particular cultural and political moment, they also continue a longer pattern of misinformation. In particular, American society witnessed an incredible outpouring of unfounded rumors around the influenza pandemic at the tail end of the First World War—a little-known history that can shed light on some of the causes and consequences of today’s coronavirus conspiracy theories.

In late 1918, as four years of global conflict were finally coming to a close, the world found itself at war once again. This time, the enemy was far deadlier, moving invisibly through society. The pandemic attacked the young and old, the healthy and the sick, with equal zeal and eventually claimed an estimated 50-100 million lives worldwide.

In October 1918 alone, Americans witnessed nearly 200,000 of their countrymen succumb to the so-called Spanish flu, a toll which roughly quadrupled the nation’s combat deaths during the war.

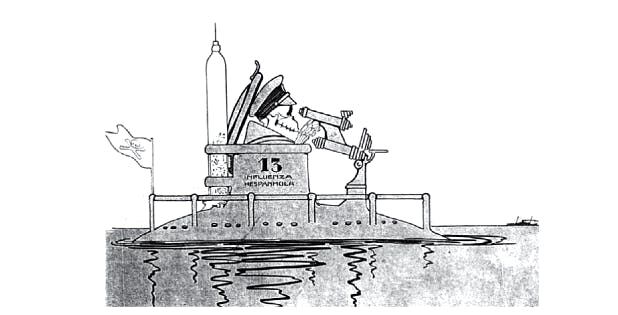

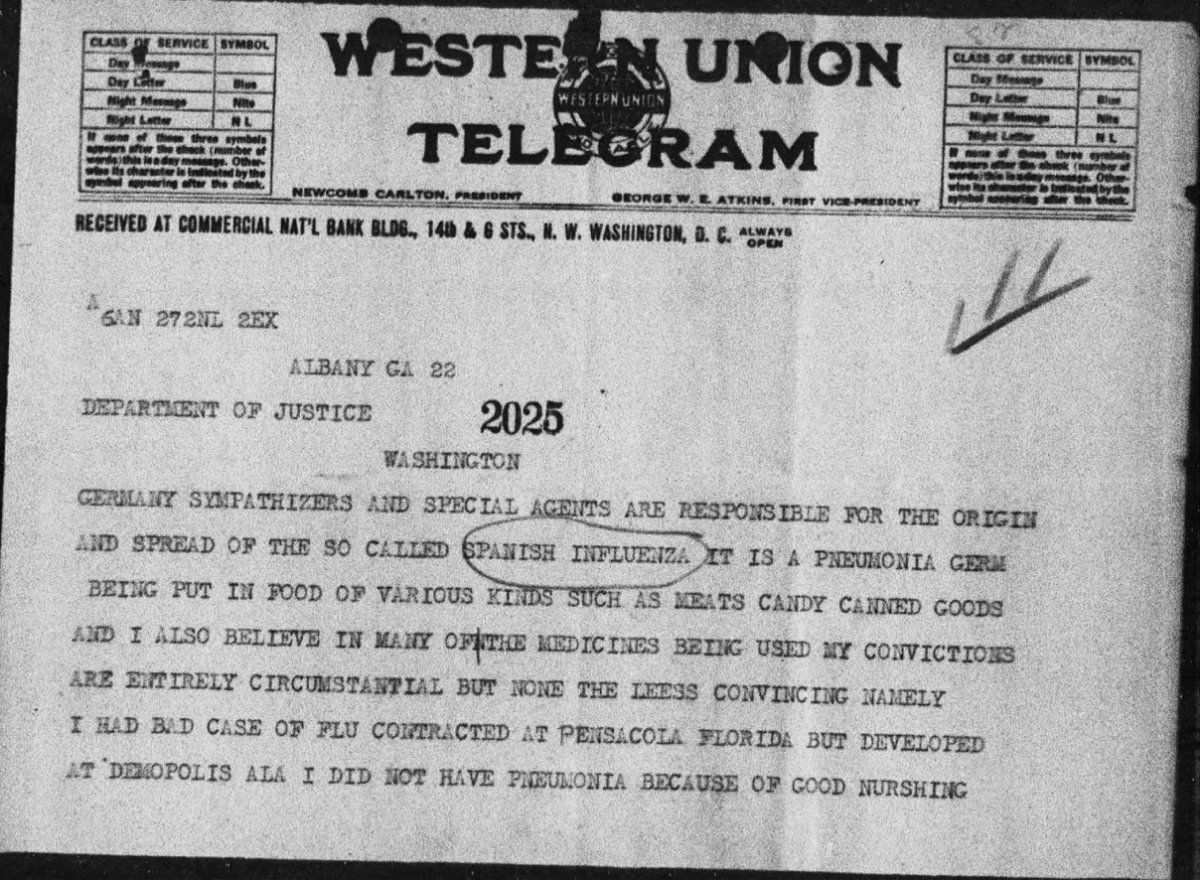

That same month, tales of the virus’s allegedly malicious origins flooded the nation, almost all of them pointing the finger at Germany. Letters poured into government investigators, speculating that everything from cigarettes, food, Baer aspirin tablets, and strangers with hypodermic needles might be spreading the disease for the enemy. One of the most frequent accusations was that it originated with spies recently brought ashore by German submarines. “It spread from the Atlantic to the Pacific in six weeks,” one man insisted. “Could it do so unless it was assisted by German agents?”

An article in The New York Times on the role of German U-Boats in spreading influenza.

With the benefit of hindsight, this widespread belief that Germany was somehow directing, or at least facilitating, the unprecedented outbreak seems a paranoid—and decidedly unscientific—explanation, but it conforms to what we know of rumors’ social and psychological function.

Decades of research by social psychologists has shown that false information often arises as a type of “improvised news” to explain worrisome and confusing events.

Indeed, during World War I, federal investigators tracking down influenza rumors often found that stories accumulated additional details with each retelling, slowly reducing an unknown threat to something familiar. If the health crisis was just another form of attack by the enemy, then it was something that Americans could see, surveil, and eventually defeat.

An October 25, 1918 telegram to the Department of Justice blaming the pandemic on German agents

Historical analyses of rumor have contributed a crucial insight to this understanding of fake news. Rumors during a time of crisis almost always reflect and reinforce cultural fears already in existence.

At the time of the Spanish flu, people across the nation were suspicious of vaccines and they repeated the assertion that doctors and nurses in training camps were intentionally inoculating the recruits with the disease.

“They arrested one of the head nurses here to-day, she is a German spy,” wrote a woman to her sister. “She is cause of more than half of the influenza in the camp…There was bound to be something wrong when the boys begun to die by the hundreds.” Governmental vaccination requirements—which included smallpox and typhoid, though not influenza, for which there was not yet a vaccine—became an easy target of the collective paranoia.

Men gargling salt water to guard against infection at Camp Dix, New Jersey, circa 1918.

The current coronavirus conspiracies have resuscitated a range of older concerns—including suspicion about the federal government and political authority, scientific expertise and technologies, mandatory vaccination, and eroding individual liberties—and effectively remobilized them against current and future public health measures.

“Plandemic” and other conspiratorial sources, for example, have already anticipated an eventual vaccine as a governmental tool for infecting people with the coronavirus. Recently, another story has insisted that Bill Gates will use a mass vaccination program to implant microchips in billions around the world, allowing him to track their movements.

A COVID-19 anti-lockdown protestor in Vancouver, Canada, May 2020

Recognizing the historical basis of the anxieties that fuel fake news also helps to reveal how our pandemic fears can revive and perpetuate hatred against groups already branded as dangerous in the popular imagination.

Rumors around the Spanish flu, for example, only added to the German spy scares and invasion panics that had gripped the country over the preceding years. Conspiracy theories’ insistence on the virus as a foreign attack echoed ideas of Germans as treacherous and further established them as outsiders.

They had either literally introduced the virus to American shores (as stipulated by the submarine stories) or else harbored so little loyalty to the U.S. that they had actively spread it within America’s borders. It was not uncommon at the time to hear descriptions of Germans as a “cancer”—a disease in themselves.

An anti-German sign in Chicago, circa 1917.

The parallels with our current moment are unmistakable. President Trump’s terminology of the “Chinese virus” and “Kung flu”—part of a broader denunciation of the disease as “foreign” by Americans across the country—has revived racist stereotypes about disease in order to marginalize certain groups.

The decision to assign viral outbreaks a racial or ethnic identity has long served as a tactic of white supremacy, and we again see its dangerous social consequences in the despicable acts of discrimination and violence committed against Asian Americans and people of Asian descent.

Finally, the conspiracies of the World-War-I era and today have both expressed a deep anxiety in the face of globalization. Americans fear that global connections have rendered them increasingly vulnerable to seeming intrusions by the outside world—whether that has meant German spies, immigrants, or a global pandemic.

A cartoon from Korean-Swedish artist, Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom depicting the racist remarks Asians have been subjected to during the COVID-19 pandemic (left). An anti-xenophobia poster displayed in the New York City subway amid intense racist attacks on the Asian-American communities, 2020 (right).

We have found ourselves with a powerful, and even frightening, reminder that events around the world can never be fully disconnected from those in Anytown, USA, and conspiracy theories have appeared once again to express anxiety and anger over our inherent interconnectedness.

Functionally speaking, today’s conspiracy theories differ little from a century ago. As we confront an unfamiliar and deeply frightening new reality, in which stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures have shattered the routines of everyday life, the imposition of explanations and stories, however improbable, offers a measure of comfort. Some have directed the blame abroad, many others inwards at our own government. Either way, naming an enemy has provided a target for collective fear and fury.

Want to Learn More?

Jean-Noël Kapferer, Rumors: Uses, Interpretations, and Images. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1990.

Michael Barkun, A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Nancy Bristow, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.