Hillary Clinton will be the first woman nominated by a major political party to run for president of the United States, but she is certainly not the first woman to seek the office. This month historian Kimberly Hamlin profiles women who have tried to win the Presidency—an office that thus far has been a club for men only.

Listen more: Violence Against Women; Reproductive Rights and Reproductive Justice; Same-Sex Marriage; Abortion in Europe and America; A Long View of Policing in America;

Read more: “Big Government” in American History; The American Two-Party System; “Class Warfare” in American Politics; American Populism; Immigration Policy; Domestic Violence; The War on Crime and America's Prison Crisis; and Policing the Police: A Civil Rights Story

On June 7, 2016, Hillary Rodham Clinton secured enough delegates to become the Democratic nominee for president of the United States. As everyone knows, this will make Clinton the first woman to attain the Democratic or Republican nomination for president. But she is far from the first woman to run.

Since 1872, fourteen women have run for president, three of whom garnered support at a major party national convention. Five were nominated as third-party candidates, and two were eventually chosen as major-party candidates for vice president.

In addition to the fourteen women who have run for president, several others have come within striking distance of the nation’s top post through the line of succession.

Representative Nancy Pelosi was second in line for the presidency from 2007-2011 (after the vice president) when she served as the first, and to date the only, female speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright (1997-2001), Condoleezza Rice (2005-2009), and Hillary Clinton (2009-2013) were fourth in line during their tenures.

Still, no woman has been elected to serve in the executive branch of the federal government. Ninety-six years after women attained the right to vote, 24 presidential elections and 14 female presidential candidates later, this uneven and long history raises a basic question: Why has it taken so long for the United States to join with the 63 nations of the world that have been led by a woman at some point between 1963 and 2014?

And, if history is a guide, might 2016 be the year that the United States finally elects its first female president? By looking at several of these women and their campaigns for the presidency we can see a few key patterns as well as the changing (and not so changing) lenses through which Americans view women.

Fear of the Other F-Word: Feminism and Victoria Woodhull

Of the fourteen women who have run for president, some ran as feminist reform candidates, a few entered public life via their husbands’ political careers (though husbands have proven a vexed issue for most female presidential candidates), and some gained traction as “law and order” candidates.

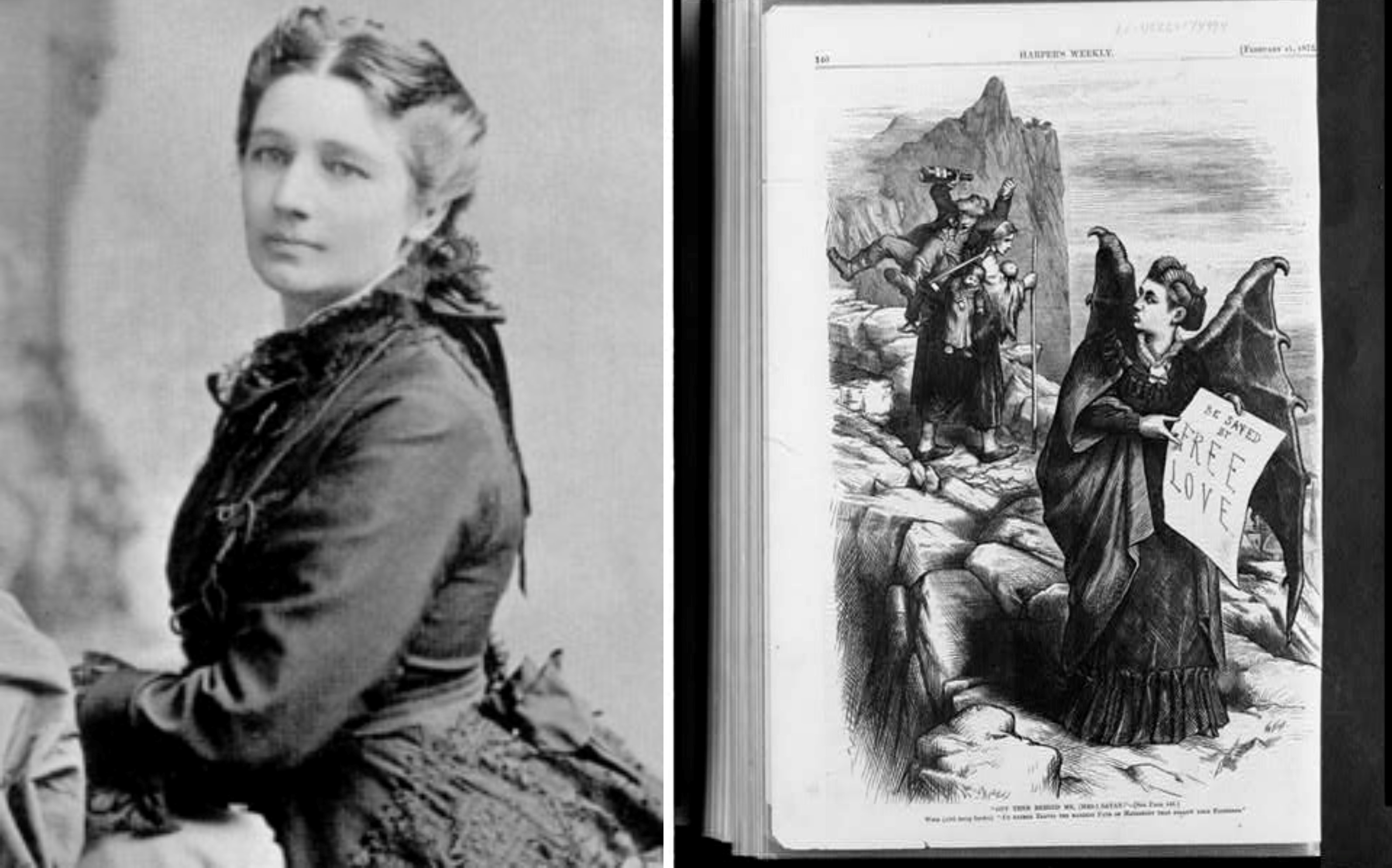

The first woman to run for president, Victoria Clafin Woodhull, ran as a feminist reform candidate—revolutionary might be more accurate—in 1872.

Victoria Clafin Woodhull ran as a feminist reform candidate in 1872 (left). Harper’s Weekly cartoon depicting Woodhull in 1872 with caption reading “Get thee Behind Me, (Mrs.) Satan!” (right).

Woodhull was born in 1838 in the tiny village of Homer, Ohio. As the seventh of ten children born to very poor parents, young Victoria complemented the family’s meager income with her skills as a clairvoyant and fortune teller. At the age of 15, she was married to Canning Woodhull, an alcoholic nearly twice her age. By 16, she had given birth to a severely disabled son. After having a second child with Woodhull, she left him and, in 1866, married Colonel James Harvey Blood and moved to New York City to begin anew.

With the patronage of the eccentric millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt, Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin set up a brokerage office on Wall Street. Among the nation’s first female stock brokers, they quickly grew wealthy. In 1870, they began publishing a women’s rights newspaper called Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly. Woodhull announced her candidacy for the presidency in her newspaper in April 1870, a full two years before the next election, and skillfully used the paper as the press organ for her campaign.

Several months after announcing her candidacy, she was nominated by the Equal Rights Party as their candidate despite the fact that, at the age of 34, she would have been too young to actually serve as president.

For a variety of reasons including but not limited to her age, Woodhull stood little chance of appearing on ballots or garnering votes but, as a protest candidate, that was largely beside the point. Woodhull’s goal was to draw attention to women’s second-class status in America in general and, in particular, to protest the recently ratified 14th and 15th Amendments, which enfranchised African American men but not women (of any race or ethnicity).

Ultimately, however, Woodhull was plagued by scandals, some of her own making and others that she publicized in her paper. In 1872, her mother took Woodhull’s second husband to court on a variety of salacious charges. The resulting court documents revealed that Woodhull lived in a house with both her first and second husbands, and a new friend named Stephen Pearl Andrews. Amidst these accusations of sexual impropriety and “free love,” newspapers across the country had a bonanza.

In response, she used her newspaper to expose the adulterous affair conducted by “the most famous man in America,” Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe. But because of the recently passed Comstock laws that prohibited the printing or mailing of anything “obscene,” Woodhull was arrested simply for writing about Beecher’s affair in her newspaper. She spent the election night of 1872 in jail.

“The First Female Cold Warrior:” Margaret Chase Smith

After Woodhull’s pioneering run, Belva Lockwood, the first woman lawyer to practice before the Supreme Court, ran for president on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1884 and again 1888. In 1916, Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first woman elected to Congress, and in 1933, Frances Perkins became the first female cabinet secretary when President Franklin Roosevelt appointed her to lead the Department of Labor.

By mid-century, women had earned a small but secure place in the federal government, though their posts were largely limited to those pertaining to women’s, family, or children’s issues. For the first half of the 20th century no woman ran for the nation’s highest office.

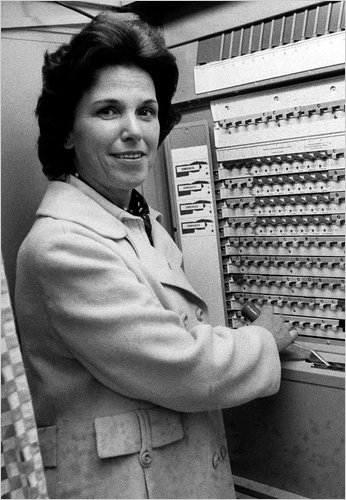

Then came Margaret Chase Smith of Maine, who sought the Republican nomination in 1964.

Smith was first elected to Maine’s one seat in the House of Representatives in 1940 to fill the unexpired term of her late husband, Clyde Smith. She had worked in Clyde’s D.C. office and harbored political aspirations of her own. Clyde endorsed her from his death bed and encouraged his supporters to vote for her in the upcoming Republican primary.

Smith ably filled her husband’s term and was re-elected to the House three more times before running for the Senate in 1948 with the slogan “Don’t Trade a Record for a Promise.” Her 1948 Senate victory made her the first woman elected to both houses of Congress.

From her very first few months in office, Smith earned a reputation as an iconoclast and a strong supporter of the military. In 1941, with World War II at the top of the nation’s agenda, Smith broke ranks with her Republican colleagues to support the first-ever peacetime draft, the Lend-Lease Act, and the arming of American merchant ships.

She later asked to be placed on the House Naval Affairs Committee and persuaded her colleagues that members of the Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Services (WAVES) should be allowed to volunteer to serve on noncombat international missions.

Known for always wearing a red rose on her lapel, Smith became famous for her 1950 speech, “Declaration of Conscience.” As a first-term senator in 1950, she had become increasingly concerned about the anti-communist rhetoric and tactics of her colleague, Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin.

Leery of communists herself, Smith repeatedly asked McCarthy for proof of the communist plots he supposedly unearthed but never saw any (to better understand communism, Smith went on an unofficial tour of 23 countries in 1954-1955). Smith worried that McCarthy was putting the powers of the U.S. government to inappropriate use in what many described as a “witch hunt.”

In what is considered one of the best political speeches of the twentieth century, Smith declared, “Those of us who shout the loudest about Americanism in making character assassinations are all too frequently those who, by our own words and acts, ignore some of the basic principles of Americanism: the right to criticize, the right to hold unpopular beliefs, the right to protest, the right to independent thought. The exercise of these rights should not cost one single American citizen his reputation or his right to a livelihood.”

One prominent observer wrote that if a man had delivered that speech, “he would be the next President of the United States.”

In January 1964, Smith announced her intention to run as a Republican candidate for president in the New Hampshire and Illinois primaries. Following her previous congressional electoral strategies, Smith declined to solicit campaign contributions, refused to campaign when the Senate was in session (lest she miss a vote), relied only on her personal money and on unpaid volunteer labor, and refused to purchase advertisements. Instead, Smith declared that she would once again run solely on her record.

For the most part, the press responded with interest to Smith’s campaign, with many stories commenting on how attractive she was … for her age. One columnist argued that she was too old, at 66, to be president because “the female of the species undergoes physical changes and emotional distress of varying severity and duration … [and these changes are] known to have an effect on judgment and behavior.”

In accordance with her busy Senate schedule, Smith campaigned in New Hampshire for just two weeks and secured only a few thousand votes. In Illinois, however, she won nearly 30% of the votes and came in second to Barry Goldwater, the eventual nominee.

That summer at the Republican convention, she received 27 first-ballot votes. Defying convention custom, Smith chose to remain in the auditorium while her name was read in front of all the delegates, savoring her place in history.

As the “first female Cold Warrior,” Smith continued to take a hardline stance on military issues and she was an early and enthusiastic supporter of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In 1972, Smith was defeated in her bid for Senate re-election by Democrat William Hathaway who criticized her support for the Vietnam War and repeatedly drew attention to her age.

The 1970s: From the House to the … House

While Smith lost her bid for re-election in Maine, in other ways 1972 was a watershed year for women running for president. One hundred years after Woodhull’s run, two women ran for president–Hawaii Representative Patsy Mink and New York Representative Shirley Chisholm — and two women received convention votes for the vice presidency, Frances “Sissy” Farenthold and Tonie Nathan.

Hawaii Representative Patsy Mink (left) and New York Representative Shirley Chisholm (right).

After decades of feminist activism, the Equal Rights Amendment passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and, the following year, Roe v. Wade affirmed a woman’s constitutional right to bodily autonomy. In this context, then, it seemed only natural that women might pursue the nation’s highest office.

Chisholm’s campaign was the most successful of these female presidential and vice presidential candidates of 1972. Before entering national politics, Chisholm had served in the New York State Legislature and worked as a teacher and director of child care centers. In 1968, Chisholm became the first African American woman elected to Congress (and she hired an almost all-female staff).

Chisholm campaigned against the Vietnam War and for the rights of women, people of color, and poor people. As a representative, she introduced legislation to increase federal funding for daycare, voted against military spending, and led the charge for federal funding of school lunch programs, among many other issues.

As Chisholm explained in her 1972 announcement speech:

“I am the candidate of the people of America. And my presence before you now symbolizes a new era in American political history… We are all God’s children and a bit of each of us is as precious as the will of the most powerful general or corporate millionaire. Our will can create a new America in 1972, one where there is freedom from violence and war, at home and abroad, where there is freedom from poverty and discrimination, where there exists at least a feeling, that we are making progress and assuring for everyone medical care, employment, and decent housing.”

In a field crowded with twelve other candidates, Chisholm emerged as a powerful voice. Wherever she traveled, large crowds gathered to hear her speak and shake her hand. Like Smith, Chisholm ran largely without the support of party insiders or financiers.

Her colleagues in the Congressional Black Caucus, which she had helped to found, accused her of not waiting her turn and let it be known that they preferred a man to be the first African American major party candidate for president. Looking back, Chisolm claimed that “of my two handicaps, being female put many more obstacles in my path than being black.”

A chic dresser in tailored outfits and perfectly coiffed wigs, Chisholm entered the race simultaneously as an outsider and an insider. In an era of widespread distrust of government and mass protest, she wanted to revolutionize a broken system from within.

Indeed Chisholm’s very candidacy was largely made possible by changes to the Democratic Party’s nomination process (from closed door meetings of insiders to public primaries) recommended by the McGovern-Fraser Commission following the disastrous 1968 Democratic convention. (The presidential nomination process has changed dramatically over the years and variations exist within parties.) Chisholm also went to federal court to challenge the policy granting televised debate time only to front-runners and won the right to appear on TV.

Chisholm hoped to use her historic candidacy to draw new people to presidential politics—inner city residents, women, people of color, and young people recently enfranchised by the 26th Amendment which lowered the voting age to 18. At the 1972 convention, Chisholm carried 151 delegates and earned the right to speak from the main podium.

While she ultimately lost the nomination to George McGovern, Chisholm considered her campaign a victory. As she recalled, “I ran because somebody had to do it first. I ran because most people thought the country was not ready for a black candidate, not ready for a woman candidate. Someday—it was time in 1972 to make that someday come.”

Feminists were not the only women to be inspired by the changing gender politics of the 1970s to run for president. In fact, the first woman presidential candidate to qualify for federal matching funds and secret service protection was Ellen McCormack who ran as an anti-abortion candidate in both 1976 and 1980.

As a Democratic candidate in 1976, McCormack secured 22 convention delegates; however, she used her federal matching funds to air what were essentially anti-abortion ads which prompted Congress to revise the rules regarding matching funds. In 1980, she ran as the Right to Life Party’s nominee and garnered more than 32,000 votes in the three states in which she appeared on the primary ballot.

In the 1980s, two third-party female candidates for president also qualified for federal matching funds: Sonia Johnson who ran on the Citizens Party ticket in 1984 and Lenora Fulani who ran on the New Alliance Party ticket in both 1988 and 1992.

The Vice President, or the President’s Office Wife

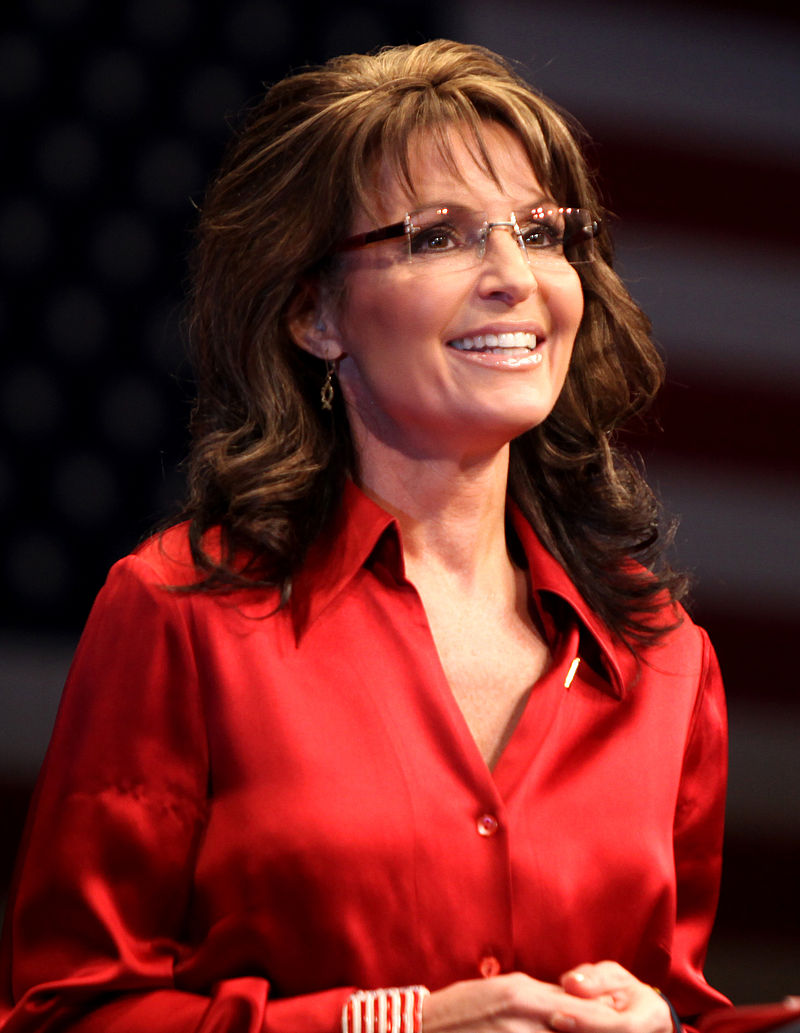

Besides Representative Pelosi and the three female secretaries of state, the women who have come closest to actually serving as president are the two major-party nominees for vice president: Geraldine Ferraro and Sarah Palin.

Ferraro ran as Democrat Walter Mondale’s vice president in 1984 against Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Ferraro grew up in New York City, graduated from Fordham law school, and, from 1973 to 1978, served as assistant district attorney in Queens, prosecuting sex crimes, child abuse, domestic violence, and crimes against the elderly. In 1978, Ferraro ran for Congress with the campaign slogan “Finally a Tough Democrat.” She won handily.

Like Margaret Chase Smith, Ferraro combined a pleasing feminine exterior—smart dresses and pearls—with tough stances against crime and in favor of the military. Headlines of her candidacy often included the phrase “tough lady.”

Ferraro was also a fierce advocate for women and women’s rights, supporting both the Equal Rights Amendment and the Women’s Economic Equity Act, and she later served on the board of Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Like Woodhull, however, Ferraro was plagued by scandal, most of which related to her husband’s business activities and alleged ties to the mob (charges that she denied but which continued to haunt her throughout her career).

Twenty-four years later and from the other side of the political spectrum, Sarah Palin also combined feminine attractiveness with hawkish talk about crime and foreign policy. Running in 2008 as the vice-presidential candidate on the Republican ticket with John McCain, Palin’s tough-but-pretty persona and anti-feminist agenda failed to register with the majority of voters. But she catalyzed Tea Party members and her outraged outsider strategy “paved the way for [Donald] Trump,” if not for other female candidates.

Since the “Year of the Woman” in 1992, female candidates have been elected to Congress and governorships in record numbers (though women still have a long way to go to reach parity—in 2016, six out of 50 governors are women, 20 out of 100 Senators are women, and only 84 out of 435 members of the House are women).

Why not president?

One traditional answer has been lack of military service. In the era in which male presidential candidates were often war heroes and in which women could not serve in combat, this answer made some sense. But today, when the past three male presidents were not war heroes (and in each case defeated war heroes) and when women are slowly but surely entering combat roles, this answer seems unsatisfactory.

In addition to biased media coverage and deeply entrenched sexism, others speculate that the U.S. has not yet elected a woman president because, unlike many other nations with elected female leaders, America was never a monarchy and thus has no precedent of a queen.

Women in the White House, But Only on TV

Without historical images of women rulers, Americans turn to popular culture for visual depictions of women presidents. The actor Dennis Haysbert played an African American president on the popular Fox show “24” and claimed that this portrayal helped pave the way for the election of Barack Obama in 2008. Some media observers agree.

What about female presidents in popular culture? The short answer is that, for the most part, women appear mainly as vice presidents.

One of the best depictions of the double standard(s) facing women candidates for high office was the 2000 Rod Lurie film “The Contender.” In this Oscar-nominated drama, Joan Allen plays a Senator who is nominated to fill the office of vice president after he is assassinated, until photos emerge that appear to depict her engaging in raunchy sex at a college party.

Joan Allen as Senator Laine Billings Hanson (left) and Geena Davis as Vice President MacKenzie Allen (right).

Lurie followed up with the ABC show “Commander in Chief” starring Geena Davis which ran for one season in 2005-2006. In this series Davis’s character, MacKenzie Allen, also begins as vice president. The dying president urges her to step down and let a “more qualified” candidate fill his shoes, but Allen refuses. The show was canceled, its poor ratings often compared against those of ABC’s concurrent hit “Desperate Housewives.”

Unlike Davis’s MacKenzie Allen, Julia Louis Dreyfus’s vice president (Selina Meyer) does get to become president on the acclaimed HBO series “Veep.”

Julia Louis Dreyfus as Vice President Selina Meyer (left) and Alfre Woodard as President Constance Payton (right).

It does not work out so well for the female vice president on “Scandal,” however, who sees her hopes to unseat the president dashed. In 2014-2015, Alfre Woodard starred as the first African American female president on the NBC series “State of Affairs;” it too was canceled after just one season.

On screen and in reality, it seems that Americans are more comfortable with the idea of women serving as vice president, rather than as president. This may be because the vice president functions sort of like the president’s so-called office wife.

Presidents select their vice presidents in part to balance out their own deficiencies. Vice presidents go places the president doesn’t want to go to, talk to people the president doesn’t want to talk to, and do the “less important” things around the (White) House. Such tasks are traditionally gendered female which may make voters more comfortable seeing a woman in this supportive, helper position.

Will 2016 Be the Year of the Woman President?

For Americans who are interested in having a woman president, what does all this mean?

Historical examples reveal, not surprisingly, that female candidates are held to a higher moral standard than are male candidates; they are much more heavily scrutinized in gender-biased ways by their colleagues, the media, and voters; they are often held accountable for the scandals of their husbands.

They tend to fare better when they run as feminine but tough on crime and/or pro-military, rather than as overtly feminist; and voters seem most comfortable with a Virgin Mary sort of female candidate—attractive and maternal, but not sexual.

Yet Shirley Chisholm’s revolutionary and inclusive campaign for “the people” generated more enthusiasm and more delegates than any other female candidate for president prior to Hillary Clinton.

And women presidential candidates, with the possible exception of Smith (who did argue on behalf of women in the military), have also used this very public platform to successfully generate national discussions of women’s issues, even if, or maybe because, they knew they were unlikely to win.

Furthermore, since 2000, at least one woman has run for president in at least one of the two major parties’ primaries: Elizabeth Dole (2000), Carol Mosely Braun (2004), Hillary Rodham Clinton (2008), Michelle Bachman (2012), and both Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina in 2016. In contrast, no woman ran for a major party nomination for president in the 1990s. The train is coming.

History also reveals that the extension of rights to African American men tends to be followed by the extension of rights to women, white and black. So, even though President Obama defeated Hillary Clinton in 2008, his election might in fact herald the election of a woman very soon.

Overall, history shows that the momentum to elect a woman president is building, internally within female candidates, externally within at least a significant portion of the electorate, and in popular culture.

Now if only there were a woman running for president who combined the successful characteristics of the previous female presidential contenders: a reforming feminist, who entered politics via her husband; a woman who articulated a tough stance on foreign policy while wearing make-up and pearls; and a woman who had previously served in a helping capacity to the president and/or tops in the line of succession to the presidency.

Maybe, if a female candidate embodied these historical trends and characteristics, 2016 might indeed be the year that the U.S. elects its first female president.

Brown, Tammy L. “‘A New Era in American Politics’: Shirley Chisholm and the Discourse of Identity." Callaloo 31.4 (2008), 1013-1025.

Crouse, Eric R. An American Stand: Senator Margaret Chase Smith and the Communist Menace, 1948–1972. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010.

Everbach, Tracy. “‘American Women Never Again Will be Second-Class Citizens: Analyzing New York Times Coverage of Geraldine Ferraro's 1984 Vice-presidential Bid,” Southwestern Mass Communication Journal 29 (2014), 1-30.

Fitzpatrick, Ellen. The Highest Glass Ceiling: Women’s Quest for the American Presidency, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Fitzpatrick, Ellen. “The Unfavored Daughter: When Margaret Chase Smith Ran in the New Hampshire Primary,” The New Yorker online, February 6, 2016: http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-unfavored-daughter-when-margaret-chase-smith-ran-in-the-new-hampshire-primary

Frisken, Amanda. "Sex in Politics: Victoria Woodhull as an American Public Woman, 1870- 1876." Journal of Women's History 12.1 (2000), 89-111.

Frisken, Amanda. Victoria Woodhull's Sexual Revolution: Political Theater and the Popular Press in Nineteenth-century America, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Sena, John F. “A Picture is Worth a Thousand Votes: Geraldine Ferraro and the Editorial Cartoonists,” Journal of American Culture 8 (Spring 1985), 2-12.

Sherman, Janann. No Place for a Woman: A Life of Senator Margaret Chase Smith. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

Sherman, Janann. “They Either Need These Women or They Do Not: Margaret Chase Smith and the Fight for Regular Status for Women in the Military, The Journal of Military History 54 (January 1990), 47-78.

Wallace, Patricia Ward. Politics of Conscience: A Biography of Margaret Chase Smith, Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, 1995.

The House of Representatives also maintains wonderful historical databases on the Members of Congress, including the three women Representatives chronicled here who also ran for President or Vice President: Reps. Smith, Chisholm, and Ferraro:

http://history.house.gov/People/Detail/13081

http://history.house.gov/People/Listing/C/CHISHOLM,-Shirley-Anita-(C000371)/

http://history.house.gov/People/Detail/21866

For more on Smith’s “Declaration of Conscience” speech, http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Speeches_Smith_Declaration.htm

In addition, there are excellent documentary films about Ferraro and Chisholm:

“Ferraro: Paving the Way” (2014), produced and directed by Ferraro’s daughter Donna Zaccaro, http://www.ferraropavingtheway.com/

“Chisholm ’72: Unbought and Unbossed” http://www.pbs.org/pov/chisholm/