On the night of March 5, 1770, a man and a British sentry exchanged heated words in Boston, Massachusetts. Within minutes, three people lay dead in the snow and several others were injured, two fatally. This event, popularly referred to as the “Boston Massacre,” was a turning-point in relations between American colonists and British authorities, and provided one of the sparks that would ignite the American Revolution.

Two regiments of British troops had occupied the city of Boston since September 1768, after residents had resisted taxes levied by Parliament on goods like tea and paper to pay for the costly French and Indian War. Sent to enforce these taxes and keep the peace, the more than one thousand soldiers were heavily resented by Bostonians as an affront to their local autonomy.

A 1770 engraving by Paul Revere depicting the arrival of British troops in Boston in 1768.

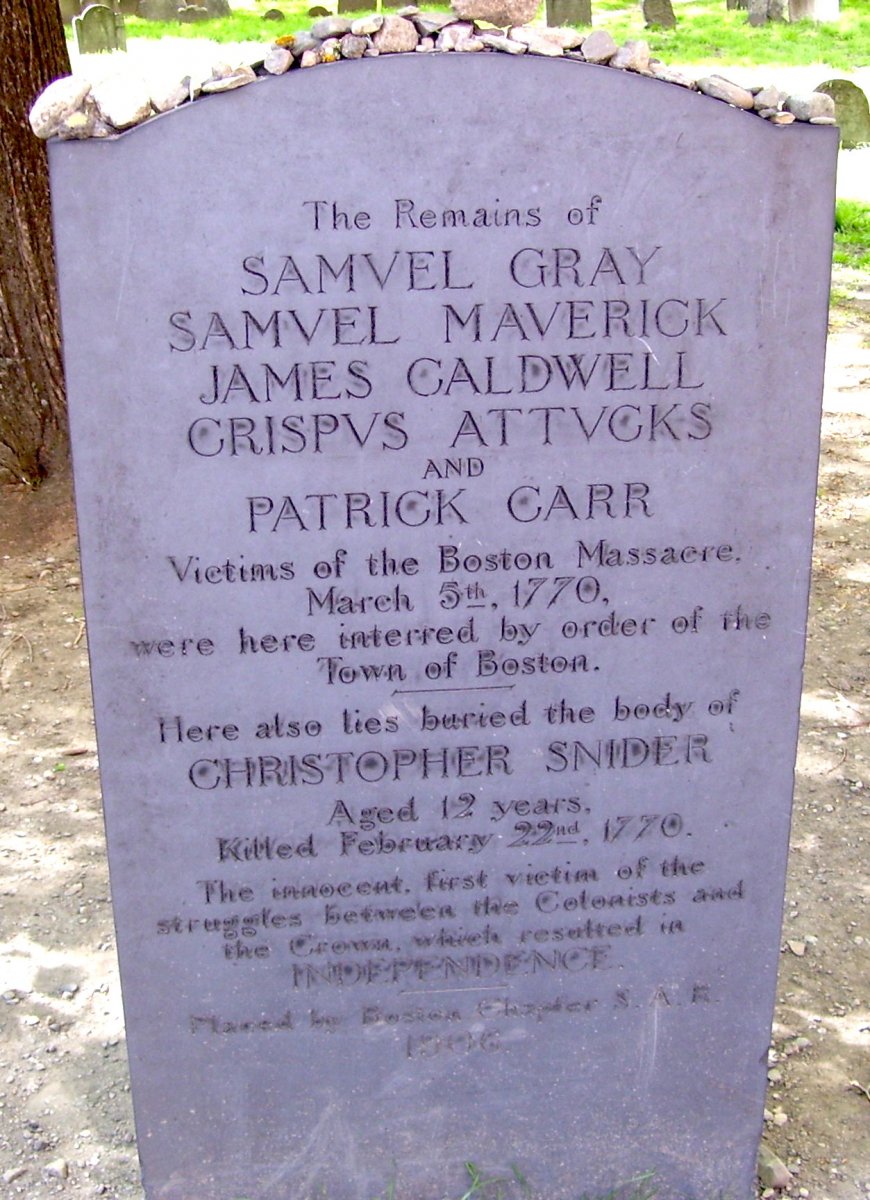

From the beginning of the occupation, conflicts periodically flared up between British soldiers and townspeople and by early 1770, fights had become commonplace. The death of a young man, Christopher Seider, during one such clash the previous month only exacerbated tensions and put much of the town on edge.

Numerous skirmishes between townspeople and soldiers broke out across Boston on March 5. The main altercation began in front of the Custom House, where Private Hugh White argued with a young resident over a debt. White lashed out, hitting the young man with the end of his musket. As a crowd began to gather, shouting insults and throwing snowballs, White called for reinforcements.

This 1878 engraving shows the chaos at the scene of the Boston Massacre.

Captain Thomas Preston of the 29th Regiment soon arrived at the scene with six grenadiers and formed a semicircle in front of the building, armed with rifles and bayonets. Meanwhile, church bells rang out, bringing more townspeople into the streets to join the standoff.

The arrival of the grenadiers only further inflamed the situation, and the growing crowd continued to hurl snowballs and chunks of ice at the soldiers. Captain Thomas Preston and a local man named Richard Palmes attempted to negotiate a resolution, but then a projectile hit the rifle of one grenadier, causing him to mistakenly discharge his musket.

After a pause of between five and thirty seconds, the other grenadiers shot into the crowd as people ran for cover. Three townspeople were killed instantly. Another eight were wounded, two of whom later succumbed to their injuries.

Following the shooting, Captain Preston hastily ordered his soldiers to retreat, fearing retribution. The size of the crowd continued to grow, with some Bostonians attending to the wounded while others brought muskets in anticipation of a wider fight. Preston soon ordered much of the 29th Regiment to the Custom House. As later historians have speculated, any stray shot that night could have started a war.

Although the events of March 5 ended without further violence, the following days remained extremely tense. Governor Thomas Hutchinson, the highest-ranking British administrator in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, feared that tens of thousands of colonists would pour into Boston to forcibly expel the British regiments from the town. Indeed, local Bostonian notables demanded the troops’ removal in no uncertain terms.

After the massacre, the British military occupation was clearly untenable. Seeking to calm the situation, Hutchinson arrested Preston and the grenadiers, declared that they would be tried locally, and effectively ordered the commander of the British forces to remove both regiments from the city.

The fears of Governor Hutchinson and other British administrators of a violent uprising did not come to pass. Despite the spread of anti-British propaganda throughout the colony, the removal of troops from Boston ameliorated the situation, as did the trial that quickly followed.

The grenadiers stood trial in Boston, adeptly defended by the future president John Adams. Only two of the soldiers were deemed guilty, and both eventually received light punishments. With the streets of Boston freed from British soldiers though, tensions between the colonists and the British authorities lessened.

The Boston Massacre did not immediately lead to revolution: the American Revolution would not begin for another five years. Still, the Boston Massacre imprinted into the minds of Bostonians the threat of British military occupation.

When tensions began to rise again in 1773 and 1774 with the Boston Tea Party and the subsequent passage of the so-called Intolerable Acts, Bostonians responded more forcibly than in 1770. While the American Revolution had other causes throughout the British colonies, in New England, the British military occupation of Boston remained a major factor.

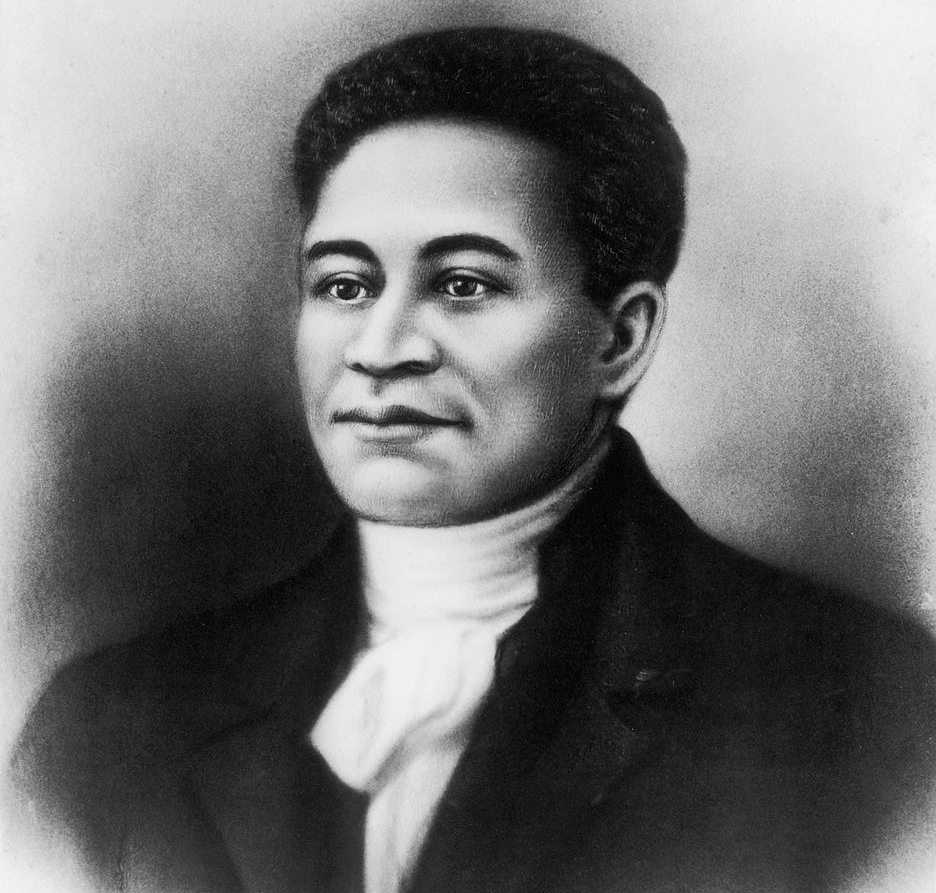

The events of the massacre reveal the social diversity and complexity of New England in the late 1700s. One of the people killed by British soldiers on March 5 was a sailor named Crispus Attucks. While little about him is known, he was probably of mixed African-Native descent. Far from unusual, Attucks’s background was representative of New England society. Slavery still existed throughout the region, and many Algonquin people lived (and still do) in their homelands in Massachusetts. Individuals like Attucks were commonplace on the streets of Boston.

The soldiers of the 29th Regiment who participated in the massacre also mirrored the diversity of the British Empire. Fifty percent of these soldiers were Irish, another seventeen percent came from the Caribbean. The presence of Irish and black British soldiers occupying Boston further inflamed white, Protestant Bostonians, many of whom held slaves and had fought against French Catholics in the French and Indian War.

The struggle of Bostonians to maintain local autonomy then occurred in a diverse and complicated British Empire, where ethnic, religious, local, and imperial loyalties diverged. The American Revolution would force people across the British colonies to choose between these loyalties.

Perhaps ironically, the collapse of the remnants of the British Empire has created a similar situation in Hong Kong in 2020 to that of New England in 1770.

In the beginning of 2019, contentious and often violent protests erupted in the city after the passing of an extradition law. The people of Hong Kong saw the law as a challenge to their local autonomy, as it threatened them with possible deportation to China for opposing China’s increasingly autocratic policies.

A crowd protesting the extradition law in the summer of 2019 in Hong Kong.

Even after the Chinese-supported chief executive of the city, Carrie Lam, finally withdrew the hated extradition law in September, the mass protests continued. The government acted too late to mollify the population. The issue for Hong Kong citizens became the question of local control, not the extradition law itself.

As in New England where the occupying British soldiers enflamed public opinion, the brutal tactics of the Hong Kong police force have become a lightning rod for the opposition in Hong Kong.

In a time of climate change, rising authoritarianism, and increasing unrest throughout the world, we would do well to review the events of the Boston Massacre and its aftermath.