In March 1941, the United States remained neutral while World War II raged in Europe and Asia, but the country was inching toward war. Newspapers announced policies to support the Allies like the Lend-Lease Act, even as isolationist sentiment earned space in opinion pages.

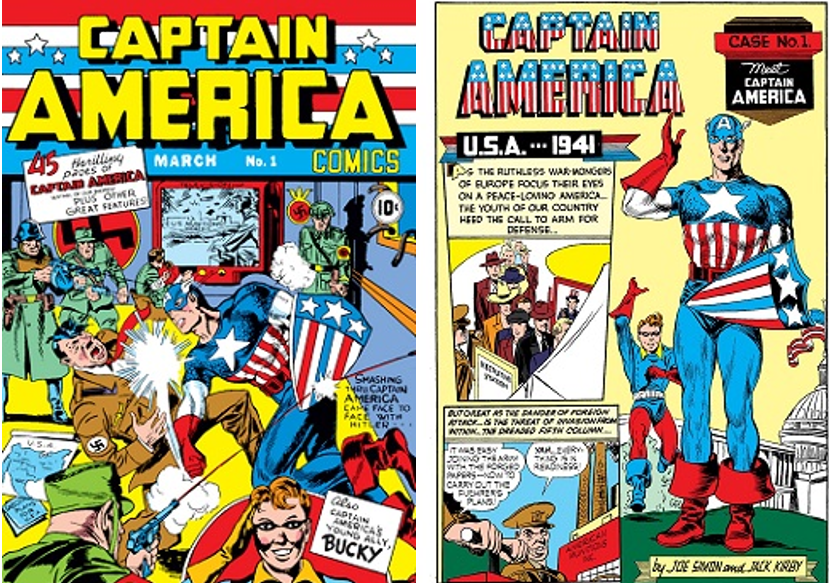

Yet next to the adult fare at the newsstands was something far less ambiguous: a four-color spectacle featuring a red, white, and blue clad figure holding a shield in one hand and using the other to punch Adolf Hitler square in the jaw.

This was the first appearance of Captain America. Created by writer Joe Simon and artist Jack Kirby in the eponymous Captain America Comics #1, the patriotic hero became a breakout star for Timely Comics (the company that would evolve into Marvel Comics).

The cover of Captain America Comics #1 from March 1941 (left). Interior artwork from the same issue (right). Artwork by Jack Kirby.

Joined by young sidekick Bucky Barnes, Captain America placed the United States firmly on the side of the Allies months before Pearl Harbor. Over the decades following his debut, Cap—as fans called him—has continued to anticipate and reflect our changing national attitudes toward war and patriotism.

Captain America was Steven Rogers, an undersized youth who wanted desperately to fight overseas. Classified “4-F,” or unfit for military service, Rogers accepted a role in an experimental program meant to create an army of super soldiers to defeat the Nazis, only to become the program’s sole success when German agents murdered the scientist leading the research. Together, he and the United States would—in the words of the first issue— “gain the strength and the will to safeguard our shores.”

Nine months after Captain America’s first appearance, the United States entered the war for real. While superhero rivals Batman and Superman mostly stayed home, Timely plunged Cap into battle in Europe and the Pacific.

Stories of fanciful Nazi invasions reinforced the real sense of insecurity that accompanied the war, while stereotyped depictions of Japanese enemies mirrored the dehumanizing propaganda used by allied governments.

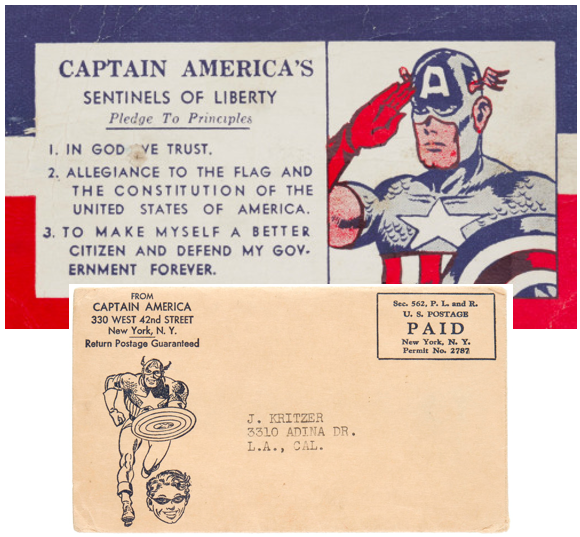

Captain America’s Sentinels of Liberty membership card, 1941 (top). Captain America's Sentinels of Liberty kit postage, 1941 (bottom).

These dynamic adventures made Captain America an unofficial part of the war effort. His winged visage enlivened patriotic calls for children to collect scrap metal and buy war bonds. Fans could join the Sentinels of Liberty, whose card featured a saluting Cap alongside a set of principles that pledged members to honor God, the constitution, and their duties as citizens.

Captain America Comics continued to be published until 1949, but postwar sales faltered without a real-world conflict to give the character weight.

The Korean War brought Rogers (now a professor!) out of retirement as “Captain America, Commie Smasher!” in 1953, but Korea was no substitute for the “good war.” Four-color McCarthyism could not pull enough coins from adolescent pockets to prevent the superhero revival from fizzling.

Still, it was hard to keep a good character down. The iconic duo of artist Jack Kirby and writer Stan Lee brought Cap back for good in 1964, during the self-proclaimed Marvel Age of comics.

A 1992 photo of Jack Kirby from The Art of Jack Kirby (left). Stan Lee speaking at the 2014 Phoenix Comic-Con. Image by Gage Skidmore (right).

Lee rejected the simplistic, perfect heroes that typified previous comics in favor of fantastical soap operas grounded in very human emotions, where heroes bickered and faced personal crises, punctuated by kinetic fights choreographed by Kirby.

Ignoring the 1950s revival, Lee and Kirby had the Avengers fish Captain America out of an ice flow where he had lain since World War II. They positioned the character as a time-tossed representative of old-school American values set adrift in the turbulent 1960s. This contrast became an essential element of the Captain’s mythos and a ready plot device for both celebrating and critiquing contemporary society.

The resulting stories increasingly distanced Cap from the realities of the day while reinforcing the national celebration of World War II as the good war fought by the greatest generation. After a brief trip into North Vietnam in 1965, Captain American generally avoided the conflict—and the larger Cold War—as it became increasingly unpopular with Marvel’s college-age fanbase.

Instead, the Captain faced a rogue’s gallery centered on unrepentant Nazis, such as the Red Skull and Baron von Strucker’s fascist Hydra organization. As anti-war protests roiled the nation, the best way to preserve the altruistic self-conception of U.S. power at the core of Captain America was to tie him inextricably to past glories.

More than just a man out of time, Captain America became a symbol out of time.

Cover of Secret Empire #1 (May 2017). Artwork by Mark Brooks (left). Teaser poster for Secret Empire. Published by Marvel Comics (right).

The dramatic tension between Cap’s timeless ideals and the churn of contemporary politics reached its apex amidst the Watergate scandal of 1974. In an obvious allegory of Nixonian malfeasance, the multi-issue Secret Empire arc culminated at the White House, where writers implied the president—who commits suicide in the Oval Office before a stunned Rogers—had been at the head of an evil cabal.

The Secret Empire story fundamentally transformed Captain America’s relationship to the U.S. political project. Lamenting he had to watch “everything [he] fought for become a cynical sham,” Captain American temporarily gave up the shield.

Writers used Captain America’s disillusionment during this period to explore the darker side of American politics and policy, without abandoning the superhero genre’s ultimate optimism.

They rewrote (retconned in comic-speak) the McCarthy-era Captain America into a jingoistic stand-in, turned racist villain and temporarily replaced the idealistic Rogers with a brash, violent anti-hero during the Reagan Era.

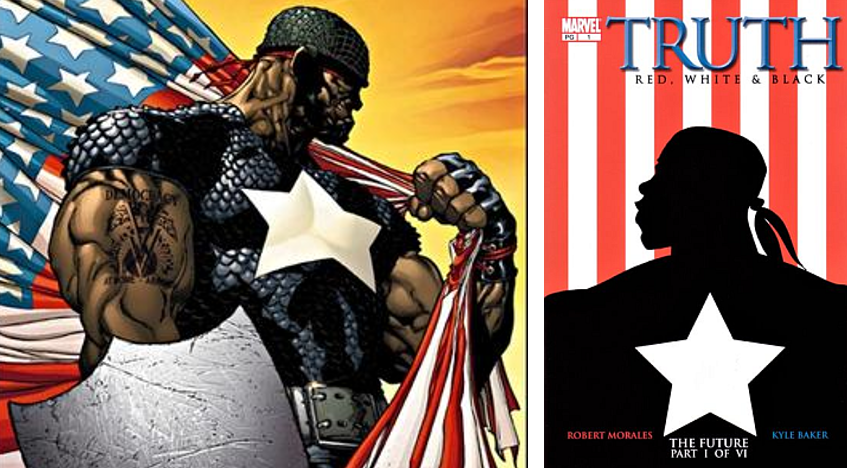

Isaiah Bradley, a black Captain America born out of experiments on hundreds of African Americans. Promotional image from Marvel.com (left). Artwork for the cover of Truth: Red, White & Black 1 (Jan, 2003) featuring Isaiah Bradley as Captain America. Art by Kyle Baker (right).

In the 2000s, one miniseries even adapted elements from the historic Tuskegee Study to portray World War II era scientists creating a second, black Captain America by experimenting on hundreds of African Americans.

Even as the subject matter of Captain America's storylines grew more morally complex, writers continued to position Steve Rogers himself as a paragon of increasingly rare virtue. He became Marvel’s personification of a vague, idealized “American Dream”—exemplified by 1980’s Cap for President! story—that contrasted with the more ambiguous reality.

This meant keeping the hero at arm’s length from the government post-Watergate, even when 9/11 gave Rogers a reason to fight. While Cap did square off against Al-Qaeda and bomb-wielding terrorists, by 2004 he was also defending an Islamic scholar held unjustly in Guantanamo Bay by overzealous military officers.

More than a patriotic hero, Captain America became a symbol of the nation’s conscience.

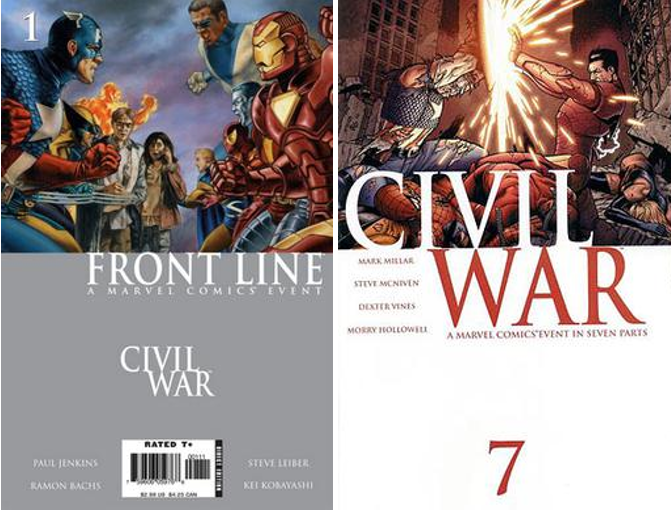

It was a version of this Captain America that formed the loyal opposition in major storylines like the massive 2006-2007 Civil War crossover event—with its allegorical allusions to the War on Terror and the PATRIOT Act—and ultimately moved beyond comics when Chris Evans’s affable Steve Rogers became the moral center of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

The cover of Civil War: Front Line #01. Published by Marvel Comics (left). Cover of Civil War 7 (Jan, 2007). Art by Steve McNiven (right).

Cap’s inherent morality made the 2017 storyline that saw a (false) Captain America lead Hydra’s takeover of the United States all the more shocking to many readers, even as a commentary on the global surge in authoritarian nationalism. (The real Steve Rogers won out in the end, of course, with help from longtime ally The Falcon.) Recent issues have seen writer Ta-Nehisi Coates explore the process of burnishing a tarnished symbol.

Such storylines have fed culture-war criticisms that comics have become too political in recent decades, or perhaps too politically correct. But as Captain America’s 80-year history reveals, this is far from a new development.

From his origins in World War II, Captain America waded into national debates with sometimes blunt force. Since the 1960s, his stories have reflected complex ideas about patriotism, recognizing national flaws while clinging stubbornly to an inherent, even exceptional belief in the United States.

Want to Learn More about Cap?

Joe Simon et. al. Captain America: Evolutions of a Living Legend (Marvel, 2019)

J. Richard Stevens, Captain America, Masculinity, and Violence: The Evolution of a National Icon (Syracuse, 2018)

Matthew J. Costello, Secret Identity Crisis: Comic Books and the Unmasking of Cold War America (Continuum, 2009)