Just past noon on Monday May 4, 1970, a squadron of Ohio National Guardsmen opened fire at a loose collection of students gathered across an expanse of leafy lawns and campus parking lots at Kent State University in northeastern Ohio. Four students were killed. Nine others were wounded. With that, the forces of order in the United States had launched a shooting war against their own children.

The May 4 incident at Kent State University was one of those rare events that seem to crystallize an entire period in snapshot brevity. It distilled the essence of an age of tumult: the young squaring off against the old; opponents of American policy in Vietnam against the Cold War consensus; or, simply, the forces of change against the forces of order.

Even the most trivial aspects of the event connected to larger developments. The most iconic image of the shootings—student photographer John Filo’s photo of Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling over the slain Jeffrey Miller—captured a fourteen-year-old girl invariably described as “a runaway” and who thereby symbolized the fraying of the ballyhooed nuclear family. Vecchio was, the Boston Globe intoned several years later, the “symbol of youth.”

“The Sixties” had its share of these allegorical moments. The firehoses at Birmingham, Mario Savio on the steps at Sproul Hall, the 1968 “police riot” in Chicago—all captured the period’s fraught social dynamics.

The Kent State killings, by contrast, were shocking because they happened in the very heart of middle America. True, Kent State was not so politically or culturally inert as many observers then and since have insisted. But that is precisely why the shootings reverberated so powerfully.

The counterculture, the antiwar movement, Black Power, and the generation gap had come even to Ohio. As the iconoclastic journalist I.F. Stone understood: “The surprise is not that there is still apathy and indifference. The surprise is that there is so much militancy, so much questioning,” in the most average of average places.

There was no stronger evidence that America was exploding at its core.

"Ohio," a protest song written by Neil Young in response to the Kent State shooting and released by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young in May 1970.

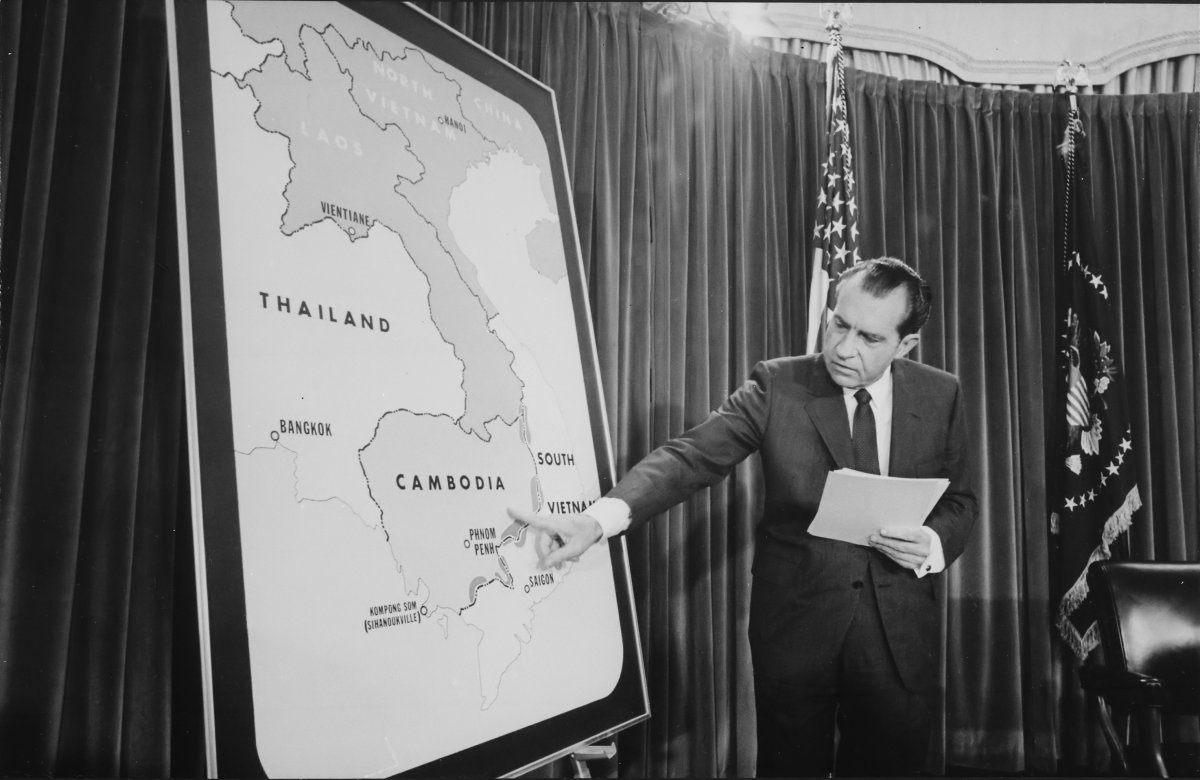

Careful scholars of the shootings are now in wide agreement about what happened. Over four days (May 1-4), initially peaceful protests against President Richard Nixon’s announcement that U.S. troops had expanded the Vietnam War into neutral Cambodia accelerated into what can fairly be called state-sponsored killing.

At each step along the way, young people aggressively testing boundaries, challenging restrictions, and engaging in political protest ran into ham-handed authorities who overreacted in an effort to impose rules for their own sake.

Because of the national uproar over Cambodia—hundreds of college campuses closed as protests erupted over the next two weeks—the atmosphere at Kent was charged. Friday afternoon campus rallies were peaceful. That night, however, students spilling out of the bars in town erupted into a melee that escalated from antiwar chants to dozens of smashed store windows; someone “liberated” a fertilizer spreader and threw it through the bank window.

The Friday night ruckus surprised hapless University officials. Local leaders insisted that “outside agitators” and “radical elements,” long presumed active in the campus area, were to blame. Kent mayor Leroy Satrom declared a state of emergency in town and established a 6pm curfew.

He also appealed to Ohio governor James Rhodes to send in the Ohio National Guard (ONG). Rhodes had deployed the Guard more times than any governor in the state’s history and obliged without hesitation. He already had directed several thousand Guardsmen to police a Teamsters’ strike in the region; they could spare a thousand for Kent.

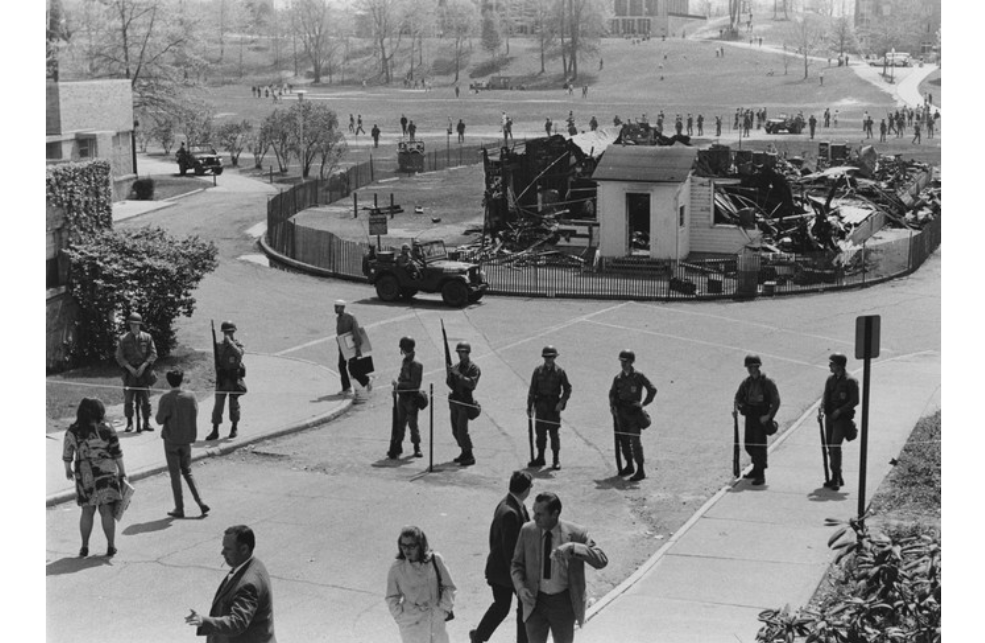

The ONG units arrived in Kent late Saturday night as fire gutted the campus ROTC building. There is little doubt that students were the arsonists. The Guard moved on campus and pushed students from the central Commons back toward the dorms. Having done so, the Guard’s commanders, Generals Sylvester Del Corso and Robert Canterbury, made clear that they recognized no boundaries between town and campus, nor did they acknowledge university officials.

Ohio National Guardsmen surround the remains of Kent State's ROTC building on May 3, 1970.

Sunday May 3 began quietly. Governor Rhodes, who had been in Cleveland, stopped at Kent on his return to the state capital, Columbus. With Del Corso and other officials in attendance, he delivered an inflammatory speech denouncing those mysterious outside agitators who were going from “one campus to the other” causing destruction. They were “worse than the Brownshirts and the communist element,” Rhodes declared. “We are going to eradicate the problem.”

Rhodes led Del Corso to believe that he approved whatever measures were necessary to “eradicate the problem,” including shooting to kill. Yet he also told university president Robert White not to close the university. That left university officials between unofficial martial law and a campus supposedly going about its normal affairs.

Documentary footage including eyewitness accounts of the Kent State shooting.

In part because of this contradictory situation, what happened on May 4 was a comedy of errors that ended in tragedy. Near noon, Canterbury led some 100 Guardsmen on to the Commons to disperse perhaps 500 students who had gathered for various reasons.

According to the Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, known as the Scranton Report after its chair, William Scranton, “some came to protest the presence of the Guard. Some were simply curious, or had free time.” The Guardsmen were equipped with tear-gas launchers, gas masks, and M-1 Garrand rifles, which were loaded with live ammunition according to Guard policy.

Ohio National Guardsmen fire tear gas at Kent State students on May 4, 1970.

The Guard moved toward the students after firing tear-gas volleys. But it was a windy day, and the gas blew, as gas does, along the wind’s whimsy. Some students laughed. But the Guard pushed most of them up Blanket Hill and down the other side, which issued through a shaded hill along the backside of Taylor Hall. Both groups moved toward a parking lot and a broad field used for football practice. Onlookers and students walking to their next class filled the area.

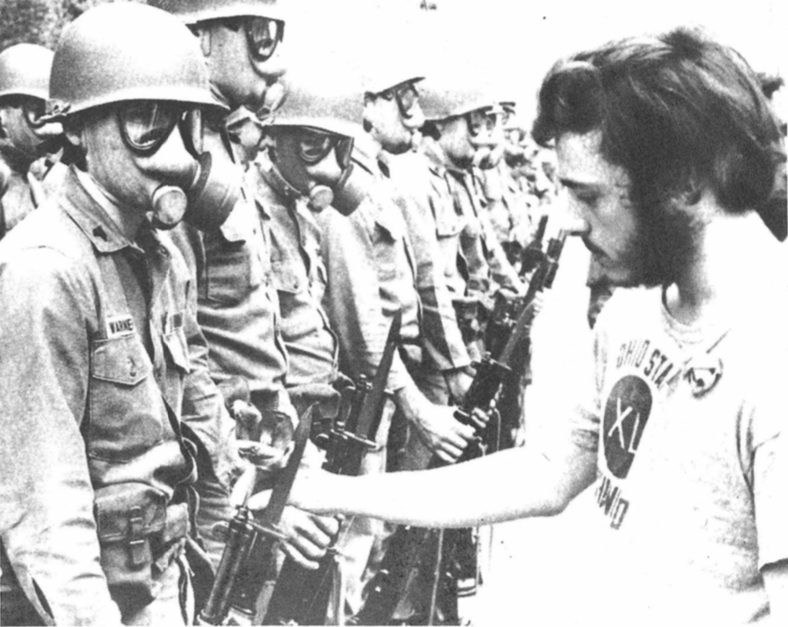

Photographs—and there are dozens, thanks to the Journalism students coming out of Taylor—show a strange scene. While the Guard, gasmasks on and loaded rifles ready, marched into the field, students with their notebooks wandered past peers who were hurling tear-gas canisters back at the Guard. Some chucked rocks; others jeered the soldiers. Many students described the atmosphere as almost carnival-like. Few imagined that the Guard’s rifles carried live rounds. As they proceeded across the field, the Guard ran into a long fence and had nowhere else to move.

Kent State students moving up Blanket Hill to avoid tear gas fired by Ohio National Guardsmen.

Canterbury claimed that having pushed the students from the Commons, he decided to go back up over Blanket Hill and return to the front of campus. As they turned to move, perhaps a dozen Guardsmen dropped to their knees and pointed their weapons. Alan Canfora, among the regular activists on campus, waved a black flag at them. They did not open fire.

Instead, Canterbury’s men got to their feet and continued back toward Taylor Hall, moving through yet more students who had been collecting along the way. Some of them came within range of rock-throwers. They were verbally abused. When they reached the top of the hill, suddenly, they wheeled around, and perhaps twenty Guardsmen opened fire. Some shot into the air, some plainly in the direction of the crowd below.

Ohio National Guardsmen advancing up Blanket Hill.

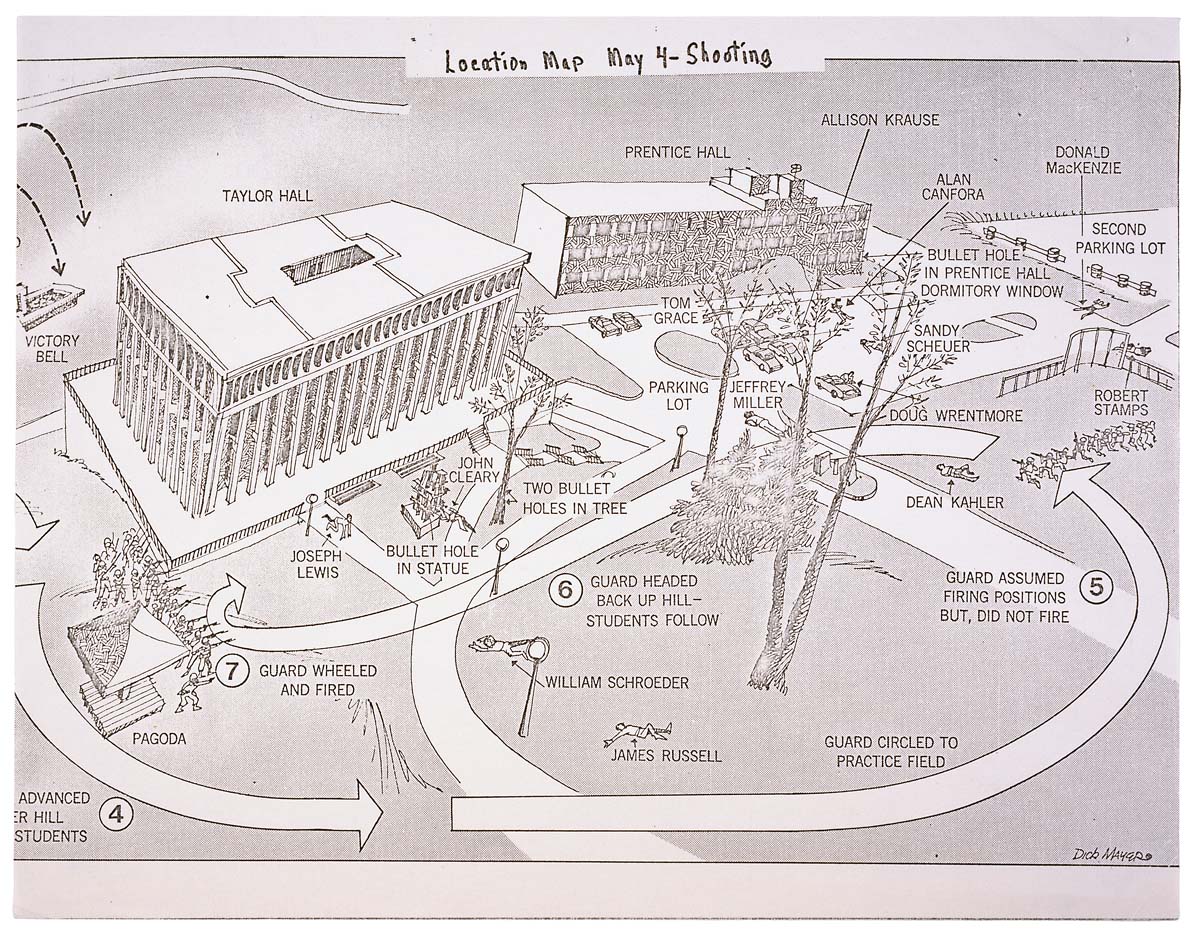

Thirteen seconds and sixty-seven rounds later, one student was dead, three others lay dying. Nine students were wounded, including Dean Kahler, who took a bullet in his spine and never walked again. The victim closest to the troops, Joe Lewis, was more than twenty yards away. His crime? He gave the Guardsmen the finger.

The nearest fatality, Jeffrey Miller, was unarmed and nearly 100 yards away. Allison Krause was unarmed and 343 feet way. William Schroeder, a ROTC member, was nearly 400 feet away, as was Sandy Scheuer, who was walking to her next class. Clearly, none presented a threat to the State of Ohio.

A map showing the location of the events of the Kent State shooting on May 4, 1970.

ONG leaders, the State of Ohio, and above all Del Corso and Canterbury had an acute interest in self-justification. Del Corso stoked rumors that the Guard had responded to sniper fire. The FBI quickly debunked “the sniper theory” by concluding simply: “There was no sniper.” The state claimed that the Guardsmen feared for their lives. The FBI suspected that these claims “were fabricated” after the fact.

The State’s legal dissembling lasted through a manipulated county grand jury, the 1973 federal indictments of eight Guardsmen charged with violating the civil rights of those they shot—all were acquitted—and its grudging 1979 agreement to pay $675,000 in civil damages to the victim’s families. Rhodes signed a letter of “regret.”

Rifles and bayonets used by Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State.

The most serious unresolved questions are whether an order to fire was given and by whom. Some men claimed they’d heard an order; others thought they heard one; and still others explained that they fired because others did. If no order was given, then Canterbury and his fellow officers failed to control their men. If the officers gave an order, then they were directly responsible for the killings.

In either case, not even U.S. Vice-President Spiro Agnew, hardly a sympathizer with the forces of change, could excuse what happened. In an interview on the David Frost Show later that week, Agnew said that a shooting that is “simply an over-response in the heat of anger . . . is a murder.”

(All images courtesy of Kent State University unless otherwise indicated.)