On a summer day in August 1920, in the middle of war, a group of Ukrainians performed Macbeth. They had been in Kyiv, but the city was destroyed, dangerous, and barely supported life, let alone theater. They traveled through a war zone to a small town called Bila Tserkva, and arrived at the tail end of fighting between Poles and Bolsheviks (the Bolsheviks won). They were not safe, not at all.

Yet in these wartime conditions, they did a play about the murder of a king and the ensuing chaos and devastation, painfully relevant to all audiences who had endured not only World War I, but also the fierce battles for control of this region after the Romanov and Habsburg empires collapsed. Audiences and artists knew uncertainty, violence, and pain.

After the war, these artists created a theater called Berezil, run by the indomitable Les Kurbas, which envisioned new horizons not only for the theater, but also for its artists and audiences. After the war, artists dreamed of changing the world.

And they did, at least theatrically. Their work highlights the innovative art of the 1920s and Ukraine’s cultural connections to Europe. And while we might think of “Soviet art” as exclusively about promoting a political message, in fact, in the 1920s, artists across the Soviet Union truly believed their work could make the world a better place.

In the 1920s, the Berezil was the largest state-funded theater in Soviet Ukraine. Based in Kharkiv, the capital of Soviet Ukraine, it produced extraordinary work. Yet it remains largely unknown today because most books on Soviet culture focus only on Moscow (or Leningrad), assuming that everything else is secondary. It is not.

Although Kurbas’ work resembles that of the (more widely) famous Soviet director Vsevolod Meyerhold, his inspiration came from a different place. For example, Kurbas grew up in the Habsburg empire, not the Russian, and different theatrical traditions and practices shaped his creativity. In some sense, we can say theater in Ukraine is distinguished from that of other parts of the Soviet Union because of different influences: the legacy of Polish culture, multiple empires (Habsburg, Romanov, Ottoman), and ultimately, the experiences of wars and occupations in the 20th century.

The Berezil and its house playwright, Mykola Kulish, created a series of touchstone productions. They include The People’s Malakhii (1927), a critique of Soviet bureaucracy about a postman with dreams of socialism who goes insane; Myna Mazailo (1929), a scathing satire on Ukrainization where no one escapes judgment; and Maklena Grasa (1933), a play about famine, created during the Holodomor, or terror famine in Ukraine. This last, unsurprisingly, led to the theater’s closure, re-naming, and the arrest of its leading artists.

But my favorite Berezil show is, in fact, not these more famous and serious plays, but rather the first Ukrainian musical revue, 1929’s Hello from Radio 477!.

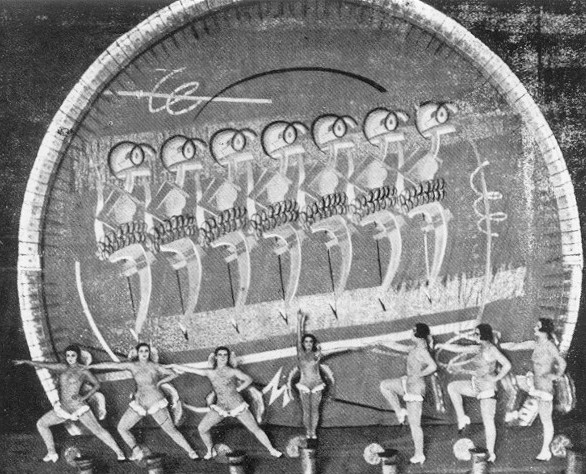

Hello from Radio 477! shows the way Europe shaped Soviet Ukraine. The production was inspired by theater in Weimar Berlin, where Berezil artists traveled in 1927 and 1928. They enjoyed shows at theaters large and small, and at famous cabarets like the Scala, known for its line of dancing girls similar to New York’s Ziegfeld Follies.

The Berezil’s managing director researched the latest in stage lighting, and the state funded the purchase of lights that would appear in Hello. The technology, the dancing girls, and the sketches based on contemporary politics and jokes, all impressed Kurbas—and he came home determined to create such a show for Soviet Ukraine. It was not ultimately directed by Kurbas, but by his three proteges, all of whom would be major figures in theater in Soviet Ukraine.

Two actors, representing Kharkiv students, served as masters of ceremonies in Act I, with jokes about the relationship with Moscow, contemporary politics, and the lack of products in the general store. Act II featured Charlie Chaplin-esque mime work by Kurbas’ wife, actress Valentyna Chystiakova, and western dances such as the Charleston. Act III brought the audience to Café “Hell,” where actors, dressed like local literary celebrities, cavorted with dancing girls.

Finally, the figure of comic writer Ostap Vyshnia was depicted hunting a line of dancing girls dressed as ducks. Ultimately, he is imprisoned in a brandy bottle by Baba Yaga, the frightening ogress of Slavic folklore.

It was a strange show, to be sure. But the jokes, the dancing girls, the contemporary references, clearly reflected the work they saw in Berlin that they transformed into a totally Soviet Ukrainian theatrical product.

Hello challenges the way we understand Soviet culture, which tends to focus on artists working in Moscow making “Soviet” art, or on non-Russian artists making “national” art. Neither paradigm captures this musical revue. It is Soviet, but it is not of Moscow. It’s Ukrainian, but it’s not nationalistic. Instead, Hello is a local product that reflects the multiple cultural influences in this place, Soviet Ukraine.

So, what happened to this remarkable theater generation?

The fate of this show and its artists are representative of Soviet Ukrainian experimental art. Hello played a season. It had a sequel (The Four Chamberlains), but in the 1930s musical comedies ceased appearing on the stages of the USSR’s dramatic theaters.

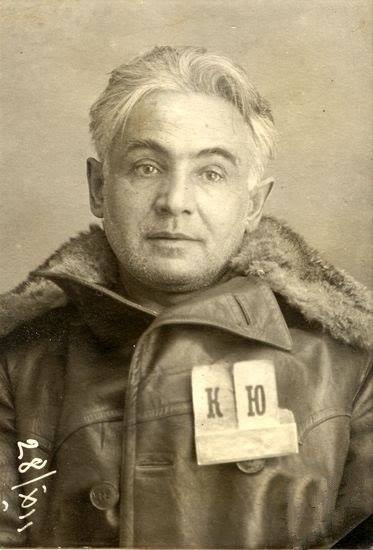

Some of the show’s artists made it to old age on Soviet pensions. Some were arrested and sent to the gulag. Some survived Nazi occupation and left for the West. Artistic director Les Kurbas was arrested in 1933 and shot by the Soviets in the far north in 1937, along with over 100 Ukrainian cultural elites, including playwright Mykola Kulish.

Their home in Kharkiv was called Budynok Slovo, the Building of the Word. Russians shelled it in early March 2022. But the photos, memoirs, and even the musical score survive and remind us of Soviet Ukraine’s innovative culture.

![]()

Learn More

Mayhill Fowler, Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine (Toronto, 2017).

Larissa M. L. Zaleska Onyshkevych, ed., An Anthology of Modern Ukrainian Drama, ed. (Edmonton and Toronto: CIUS Press, 2012).

Irena Makaryk and Virlana Tkacz, Modernism in Kyiv: Jubilant Experimentation (Toronto, 2010).

Myroslava Mudrak and Tetiana Rudenko, eds., Staging the Ukrainian Avant-Garde of the 1910s and 1920s (Rodovid, 2015).

Website: “Open Kurbas” created by Tetiana Rudenko and the team at the State Museum of Theatrical, Musical, and Cinematic Arts of Ukraine: https://openkurbas.org/en/