What happens when a hostile nation headed by an unpredictable leader acquires nuclear weapons? That's the question the world has been asking since Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un started trading puerile insults in 2017. But as historian Jonathan Hunt reminds us, world leaders faced exactly the same dilemma over 50 years ago when China, under Chairman Mao, developed its own nuclear arsenal. Those events demonstrate that the goal of nuclear non-proliferation has always been difficult to achieve.

An estimate compiled by the nation’s intelligence services reaches the president’s desk, disclosing that a formidable and reckless adversary in Northeast Asia will soon test a nuclear device. Notorious for its anti-Americanism, entry into the nuclear club by this state, whose government Washington has long refused to recognize, imperils America’s position in the Asia-Pacific.

National security officials weigh their options: to pass resolutions in the United Nations, to buoy nervous allies, to send carrier groups, to flex nuclear muscles, to draft arms treaties, to launch a preventive strike. The president instructs his national security advisor and a close family member to approach the ambassador of his country’s archrival about whether they would look the other way if U.S. bombers were to reduce this rogue state’s ballistic-missile and nuclear installations to rubble and ash.

Sound familiar?

In this case, the year was 1963, and Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China (PRC) was about to conduct its first nuclear test on October 16, 1964. How Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson dealt with the Chinese nuclear challenge set precedents for U.S.-led efforts to shutter the nuclear club, foreshadowing how the United States and the international community has treated those in pursuit of the ultimate weapon ever since, including North Korea today.

Tensions between the United States, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), and East Asian neighbors—China, Japan, South Korea, Russia—have risen. And the war of words (and tweets) between President Donald Trump and DPRK Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un has become must-see-TV. The two nuclear-armed blowhards exchange insults—“gangster,” “dotard,” “madman,” “rocket man”—with Trump boasting of his nuclear button’s size in comparison to Kim’s.

Graffiti in Vienna, Austria of U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un with their hairstyles reversed (left). One of the many Tweets from Trump in which he refers to Kim as “Little Rocket Man” (right).

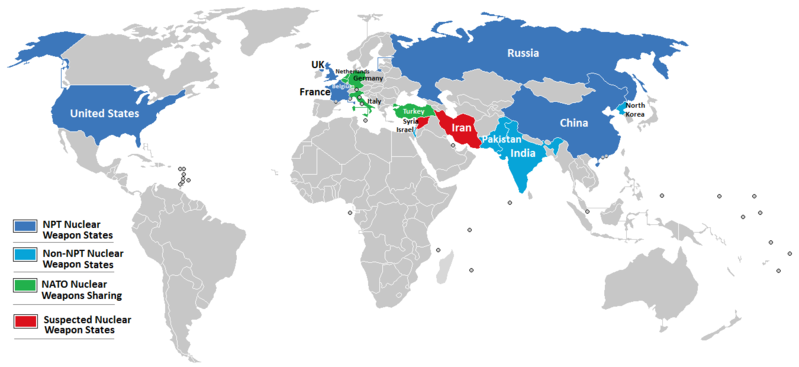

Yet these tantrums tell us little about why a military technology in the hands of eight other states—the five members of the United Nations Security Council, and India, Pakistan, and Israel—is denied the DPRK; nor about why the United States, which first built the atom bomb, now serves as the bad cop on the world’s nuclear beat. What’s missing is a history of American involvement in East Asia and the mid-century politics of nuclear proliferation during the Cold War.

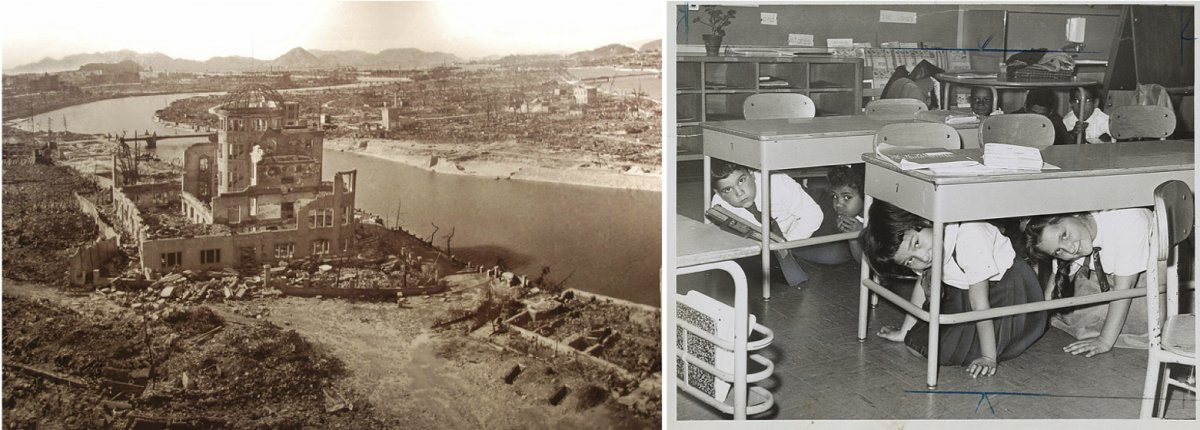

China’s nuclear test brought to a head powerful currents in the early history of nuclear science and technology—America’s military presence in Asia amid decolonization and long-running efforts to place atomic energy under international control because of its potential inhumanity.

A map depicting the nations that possess or are suspected to possess nuclear weapons.

The global nuclear nonproliferation regime, which came together with the opening for signature of the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) outlawing nuclear tests in the atmosphere, under water, or in outer space, and the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was the fruit of American efforts to weld these movements together.

The destructiveness of nuclear weapons, the revulsion toward the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the fear of fallout from atmospheric nuclear testing throughout the 1950s and early 1960s had set the tone for Washington to frame proliferation as a threat to humanity.

A view of Hiroshima, Japan after the atomic bomb strike in August 1945 (left). New York schoolchildren during a “take cover” drill in 1962 (right).

As the U.S. military found itself mired in Vietnam, China’s nuclear test in 1964 afforded an opportunity to don the mantle of global leadership on an issue of enormous gravity: policing the spread of nuclear science and technology.

Four years later, Johnson signed the NPT, the international agreement that now bars the DPRK, the Islamic Republic of Iran, and any other state save the United States, Britain, France, Russia, and China from commanding nuclear forces. Johnson vested its authority not in America’s national interests, but in “the common will of mankind.”

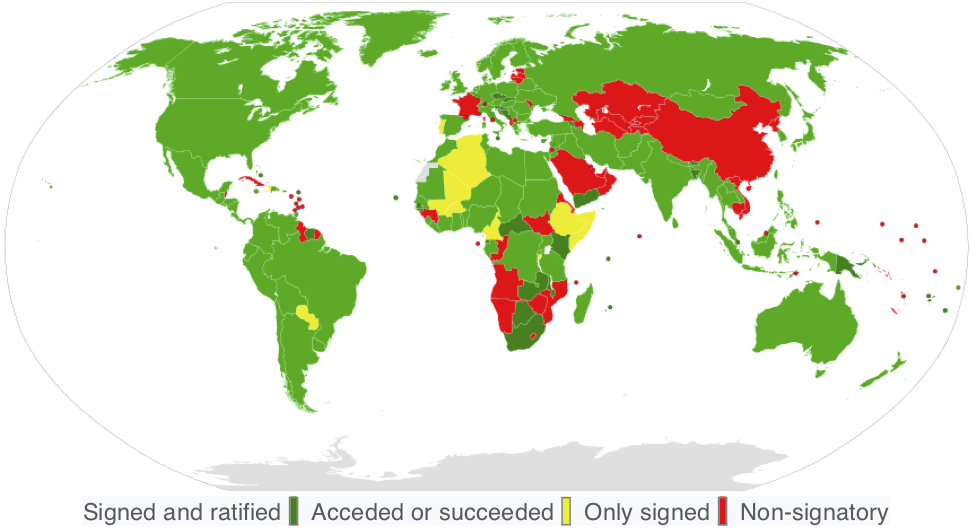

President Kennedy signing the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963 (left). A map depicting nations’ status on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as of 2013 (right).

This marriage of American military power to humanity’s law required singling out the enemies of progress, prosperity, and peace. With its revolutionary dogmatism, anti-American broadsides, and claims to represent an Afro-Asian world shaking off colonialism, Mao’s China made the perfect foil against which to justify worldwide nuclear law and order at the point of America’s sword.

Today, North Korean’s totalitarian society, starving population, litany of human rights violations, and exotic reclusion makes it a similarly useful villain for American global aspirations—another rogue state whose acquisition of weapons of mass destruction presents a legitimate target of overwhelming military action rather than firm yet patient deterrence.

News footage of President Kennedy signing the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963.

Revolutionary China and the Peril of Nuclear Weapons

Whether China would force its way into the nuclear club, and what it would do once it did, roiled the international scene in the 1950s.

Mao habitually provoked nuclear crises with U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower and the irredentist Chinese nationalists led by Chiang Kai-Shek on the island of Taiwan. In 1955, and again in 1958, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) lobbed artillery shells at nationalist military positions on the islands that hug the Chinese mainland’s coast near Xiamen in Fujian province, across the Taiwan Strait.

The U.S. carrier USS Lexington and USS Marshall off the coast of Taiwan in 1958 (left). A 1958 poster showing Chinese soldiers invading Taiwan (right).

The Taiwan Strait crises tested the posture of massive nuclear retaliation with which Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had sought to deter Sino-Soviet adventures cheaply by threatening immediate escalation to all-out thermonuclear war rather than matching the communist giants soldier-for-soldier and gun-for-gun.

Both times, Sino-American brinksmanship (what Dulles called the “necessary art” of getting “to the verge without getting into war”) brought massive U.S. naval exercises and a return to the status quo before the shelling had started. The second time, the Soviet Union, whose nuclear umbrella stretched over China, opted to do more than rap the knuckles of its daredevil ally (the Soviet Union had successfully tested its first atomic bomb in 1949).

The mushroom cloud from the first Soviet test of an atomic weapon in 1949 (left). In 1961, the Soviet Union tested the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and it remains the most powerful explosive ever detonated (right).

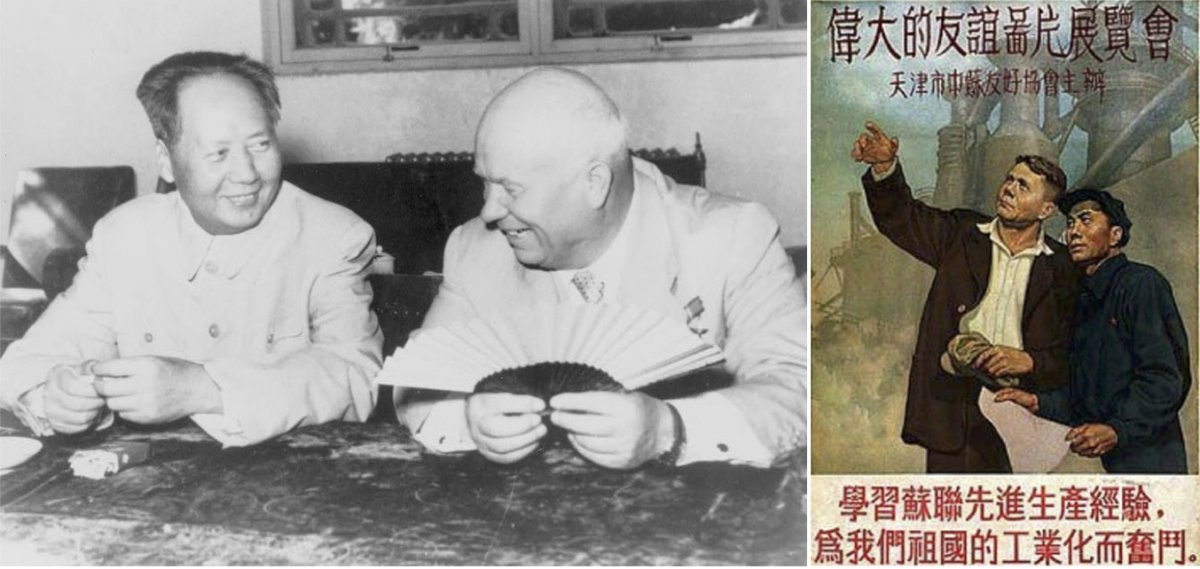

Moscow had started furnishing Beijing with nuclear assistance in the mid-1950s as part of a larger effort to modernize China’s industry and military: research reactors, scientific training, technical experts, and fissile materials such as uranium-238 (ideal for bombs).

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev promised the Chinese an atom-bomb blueprint based on the Trinity design, the first nuclear explosive tested at Alamogordo, NM, near J. Robert Oppenheimer’s Los Alamos, which a German-born, British spy Klaus Fuchs had spirited out of the Manhattan Project’s weapons laboratory.

Klaus Fuchs’s ID badge from Los Alamos National Laboratory (left). The first detonation of a nuclear weapon in July 1945 (center). A Cold-War–era billboard outside a nuclear production complex in Washington state (right).

However, Khrushchev soon moved to cut off nuclear aid altogether. The Soviet leader tired of Mao’s defiance after he had denounced Stalin’s cult of leadership (and by association Mao’s) in a 1956 speech to the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress, which soon went “viral” despite its secret nature. In 1958, Mao left Khrushchev in the dark about his planned aggression in the Taiwan Strait even though the Soviet premier had been in Beijing just days before.

Kennedy’s election in November 1960 looked like it might break the U.S.-Soviet deadlock on nuclear arms control. Kennedy found the idea of a Chinese bomb forbidding.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and Chinese leader Mao Zedong during a 1958 visit in China (left). Captioned “We use the skill of the Soviet country for the creation of heavy industry,” this 1953 Chinese poster emphasizes Sino-Soviet cooperation (right).

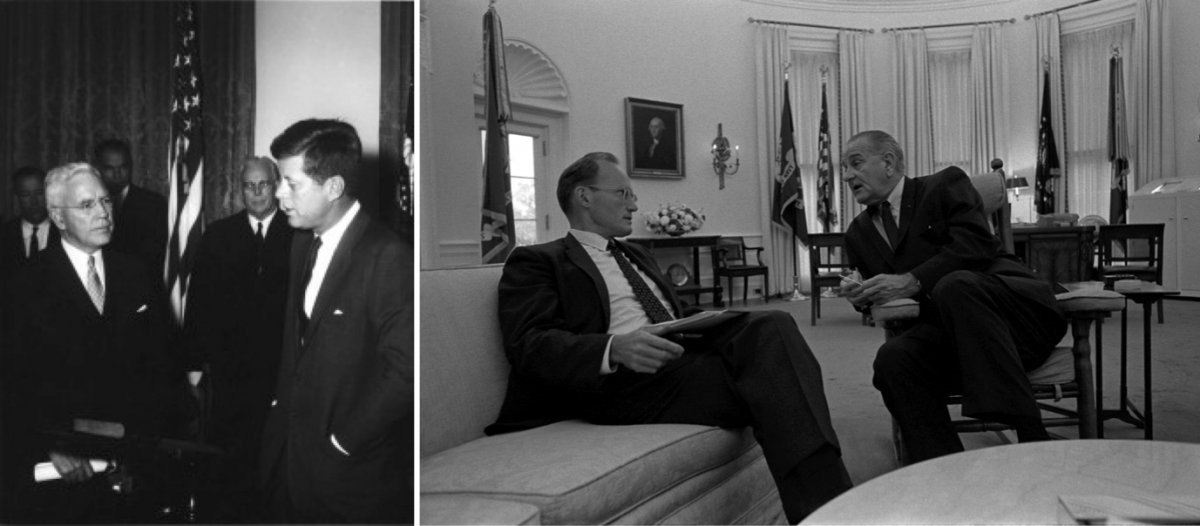

McGeorge Bundy, Kennedy’s national security adviser who stayed on to serve Johnson as well, would tell Director of Central Intelligence John McCone that Kennedy had deemed “the Chinese Communist nuclear capability ... the most serious problem facing the world today” and “intolerable to the United States.”

The president’s fears transcended the Cold War and reflected racialized fears of Asia. He believed that the People’s Republic of China was more implacable than the Soviet Union because its teeming “Asiatic” masses imperiled the United States’ global mission.

President Kennedy with CIA Director John McCone in 1961 (left). President Johnson with McGeorge Bundy in the Oval Office in 1967 (right).

Shortly after he declared that he would pursue the Democratic nomination for president, he expressed misgivings to George Kennan, an architect of America’s strategy of communist containment who was increasingly critical of the Cold War’s militarization.

Kennedy worried about Kennan’s calls for the United States to stop testing nuclear weapons, forswear their first use, and energetically seek their abolition. “I wonder if we could expect to check the sweep south of the Chinese with their endless armies with conventional forces?” he wrote.

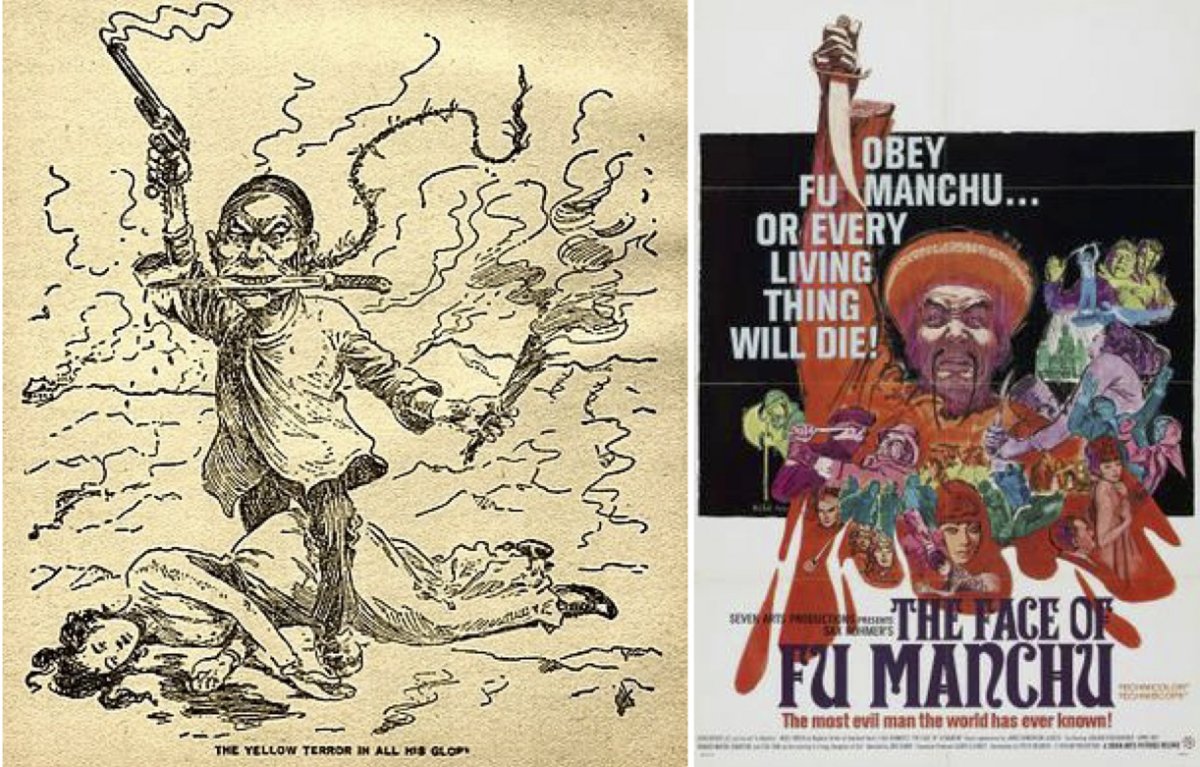

An 1899 cartoon of a Chinese man standing over a fallen white woman representing the Western world. Fears of a “Yellow Peril” or “Yellow Terror” grew in the late nineteenth century, relying on racist imagery and fear mongering. It continued thereafter as a vaguely ominous, existential fear of East Asians gaining power over Western nations (left). A movie poster for The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), a film that embodied the racist color-metaphor of Yellow Peril (right).

He could trust the Soviets, Kennedy assured a French minister after the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, to accept the condition of mutually assured destruction but “in the case of China, this restraint would not be effective because the Chinese would be perfectly prepared, because of the lower value they attach to human life, to sacrifice hundreds of millions of their own lives.”

To be fair, Mao’s own words seemed to corroborate such racist analysis. Facing the United States and its nationalist allies on Taiwan, he sought to rally Chinese society to greater exertions through saber-rattling, dismissing nuclear weapons as impotent—a “paper tiger.”

Chairman Mao at 20th Conference of World Communist and Workers’ Parties in 1957 (left). A Soviet propaganda poster captioned “Friends Forever” in both Russian and Chinese (right).

In a November 1957 speech at the 20th Conference of World Communist and Workers’ Parties in Moscow, he trivialized the aftermath of thermonuclear war:

If we fight the war, atomic and hydrogen bombs will be used. I personally believe that the whole of mankind will suffer from such a disaster, one-half of the population would be lost, maybe more than half. I have asked Comrade Khrushchev for his view of this. He is much more pessimistic than I am. I told him that if half of mankind dies, the other half would remain while imperialism would be destroyed. Only socialism would remain in the world. In another half a century, the population would increase, maybe by more than half.

This chilling statement was, in many ways, the opening salvo in the Sino-Soviet split—a burgeoning geopolitical and ideological feud between Moscow and Beijing—in which Mao championed “wars of national liberation” while Khrushchev maintained that nuclear war had made “peaceful coexistence” imperative between the capitalist and communist blocs.

Mao’s comments and his actions inspired the first proposal for a treaty to close the nuclear club to new members.

In September 1958, Irish Foreign Minister Frank Aiken introduced a proposal for “nuclear restriction” at the United Nations General Assembly that would eventually mature into the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

By the time Kennedy entered office in 1961, the Irish resolution had stalled, with Eisenhower reluctant to embrace an initiative that might jeopardize NATO’s atomic stockpile, with Khrushchev and Mao waging a battle for the soul of international communism, and with China on the verge of manufacturing its own atom bomb.

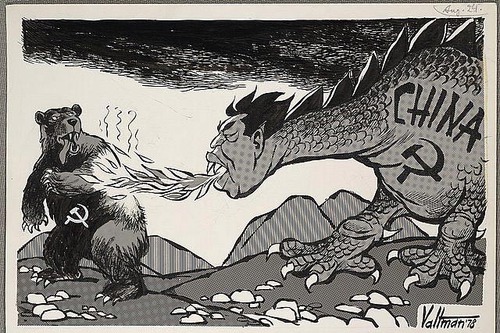

A cartoon from the 1970s depicting the Sino-Soviet split.

A Preventive Posture

The likelihood that China would build the bomb during his first term pushed Kennedy to try to avert it.

The administration had three choices: a pact to ban nuclear weapon tests; a variant of the Irish resolution; or military strikes. The first two required the help of the other nuclear powers—the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom (which had tested its first device in 1952), and France (1960). The third risked running afoul of the 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Defense, which pledged the Soviet Union to rush to the nuclear defense of its troublesome ally.

The CIA estimated that China would enter the nuclear club by 1963. The U.S. Air Force was more pessimistic, while the State Department’s Bureau for Far Eastern Affairs treated it as a foregone conclusion. Secretary of State Dean Rusk admitted to the British ambassador in Washington, D.C. that China’s progress toward an independent nuclear capability made its exclusion from arms control negotiations untenable.

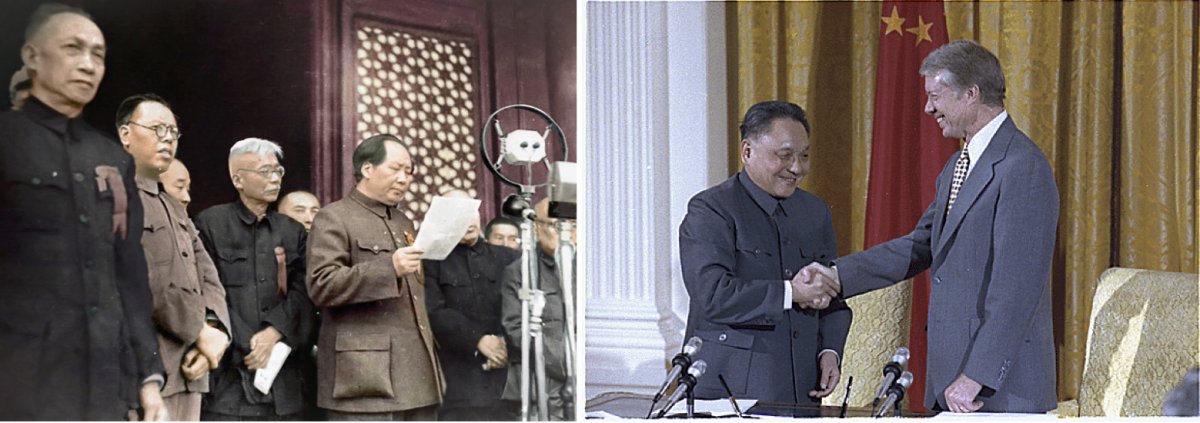

For the moment, nuclear disarmament became a public rationale for potentially engaging rather than spurning mainland China, whose communist government the United States had refused to recognize, let alone negotiate with, since its victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949.

Chairman Mao proclaiming the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 (left). President Nixon visited China in 1972, but the U.S. did not formally recognize China until 1979 under President Carter (right).

In fact, arms control could justify both China’s inclusion and exclusion from the international community, which granted Kennedy’s nonproliferation policy a flexibility born of its ambiguity. Whether China remained an international pariah would depend on its own nuclear choices.

A similar situation exists today.

The proposed summit between President Trump and Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un seems to offer a stark choice and possibly unbridgeable bargain: the normalization of U.S.-North Korean relations and the withdrawal of American troops from the Korean Peninsula in exchange for a verified end to North Korea’s arsenal of nuclear warheads and long-range ballistic missiles.

Nuclear Containment

In early 1963, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Averell Harriman was ringing alarm bells about China’s nuclear program. He related conversations with several Russians, who had mentioned that this issue concerned the Kremlin as well.

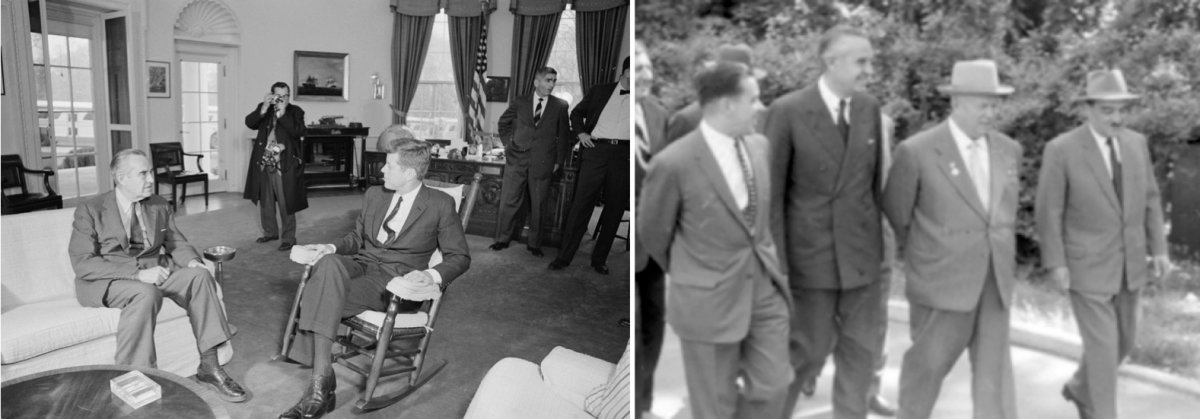

President Kennedy and Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, Averell Harriman meeting in the Oval Office in 1962 (left). Harriman (second from left) with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (third from left) in Moscow in 1959 (right).

He counseled Kennedy that an international arrangement would have the advantage of universality and impartiality. According to his Soviet friends, “world opinion” would have to follow the superpowers’ lead. He even suggested that, if all else failed, Kennedy should consider a preventive strike against China’s nuclear facilities.

For China to acquire its own atomic weapons—and China was not alone in this aspiration—heralded more than a heightened risk of nuclear war. U.S. policy-makers believed that nuclear proliferation jeopardized U.S. political and military interests across America’s globe-spanning empire of military bases, alliances, and covert assets.

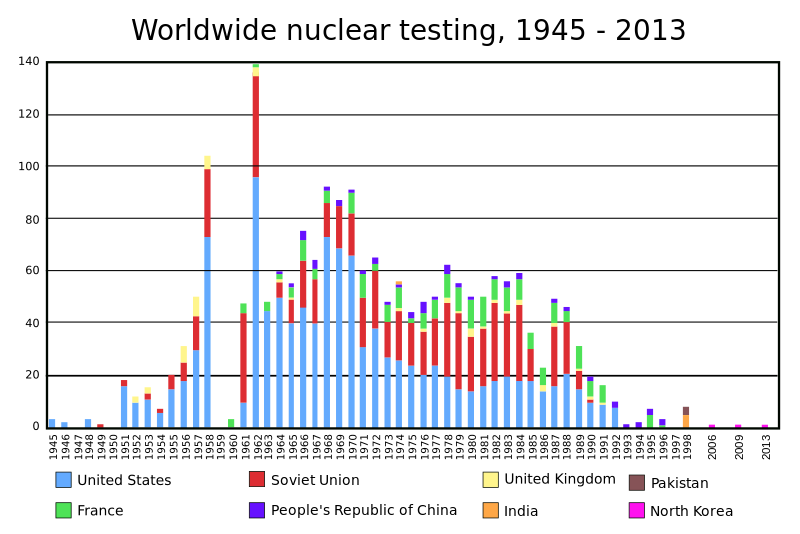

A chart depicting the number of nuclear tests by country from 1945-2013.

For U.S. officials, Mao’s China was nonetheless the most troubling “ Nth country,” referring to the theory that proliferation anywhere would beget proliferation everywhere. If China went, Japan and India might not be far behind, followed by Pakistan, Indonesia, Taiwan, Israel, and Egypt. In time, even European states like West Germany and Sweden would feel compelled to match their new Asian competitors.

Ultimately, the Kennedy administration moved to preserve American influence in a vital region and its credibility worldwide.

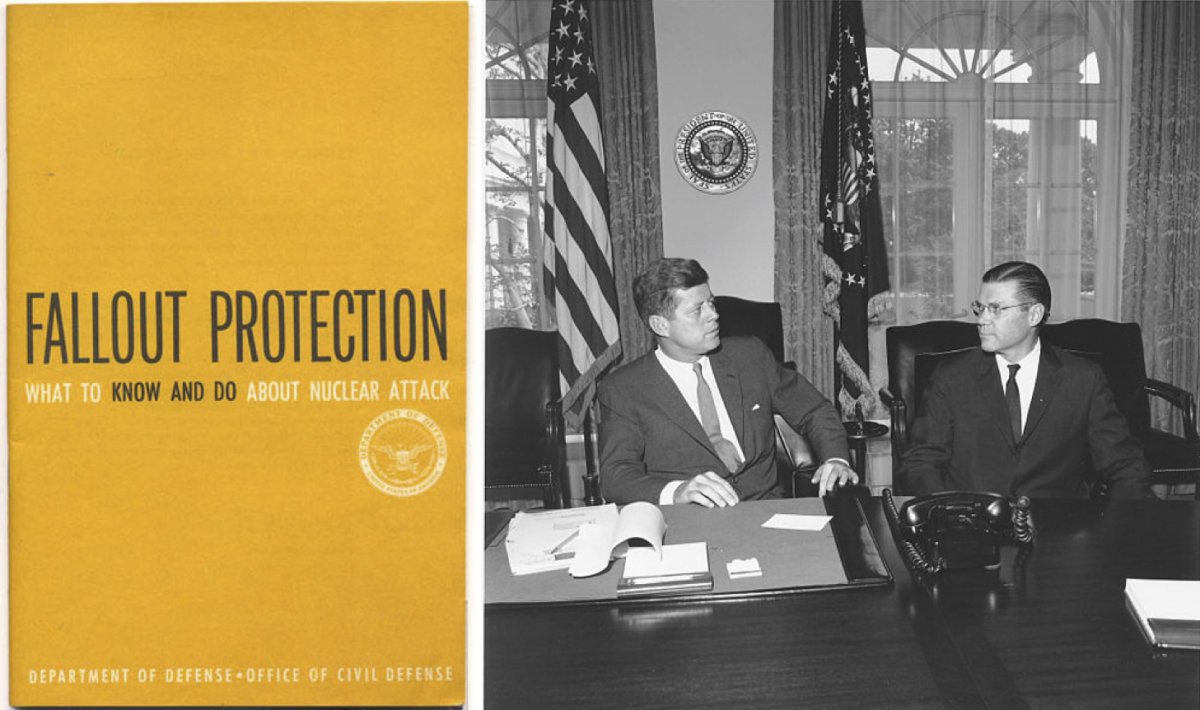

A U.S. Civil Defense booklet commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in 1961 (left). President Kennedy and McNamara meeting in the Oval Office in 1962 (right).

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara described the spread of atomic forces as a game-changer, its strategic implications calling into question the verities of the Cold War. A world in which many states fielded nuclear arsenals was no longer bipolar. From official Washington’s point of view, for Beijing to get its hands on five small atom bombs was more dangerous than Moscow acquiring another five city-busting thermonuclear warheads.

McNamara wanted a nonproliferation pact to supplement a test ban and strategic arms limitations with the Soviet Union. Whether their reach exceeded their grasp for all these international agreements was another matter. “The honest answer is that we don’t know,” he admitted. “It is equally clear that it would be irresponsible not to try.”

Mission to Moscow

It was clear to McNamara that keeping China nuclear free would require substantial leverage: export restrictions on oil, petroleum, lubricants, chemical fertilizers, and foodstuffs; perhaps even surgical strikes. Whether Khrushchev would go along was another question. Military action would have to await his “tacit consent.”

After conciliatory gestures by both Kennedy and Khrushchev, negotiators from the United States led by Harriman, and Great Britain, led by Lord Hailsham, arrived in Moscow in 1963 to explore a new treaty—a prohibition against nuclear testing in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. They would stay in Moscow for 11 days, working on a test ban, sketching out a non-diffusion pact, stalling on European non-aggression, and gauging how the Soviets felt about the People’s Republic.

The two sides saw a test ban very differently. When Harriman met with Khrushchev, the Soviet leader made clear his lack of interest in a total ban that would cover underground tests. As for China, he limited his criticisms to those based on the public battle lines of the Sino-Soviet split—peaceful coexistence versus national liberation.

When Harriman pressed him on a nonproliferation pact, he demurred, teasing the heir to an American railroad fortune that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not issue visas to capitalists. When the American persisted, he downplayed China’s nuclear potential. While they might explode a crude nuclear device, it would take a huge investment of time, energy, and resources to match U.S. and Soviet capabilities. In the wake of the disastrous Great Leap Forward, Khrushchev said, China simply lacked the wherewithal.

For all his nonchalance, Khrushchev had not dismissed the notion of U.S.-Soviet joint action against China’s nuclear program, or so Kennedy thought. From the Oval Office, he told Harriman to keep pressing because the China problem was so grave: “I agree that large stockpiles are characteristic of U.S. and U.S.S.R. only, but consider that relatively small forces in hands of people like the Chinese Communists could be very dangerous to all of us.” For now, the president argued, a limited test ban offered the best means to limit diffusion.

Harriman surmised from conversations with Yuri Zhokov, Pravda’s foreign editor, that Sino-Soviet disputes were all-consuming for the Russians.

Khrushchev wanted to use a test ban to ostracize China in world opinion, exposing it to attacks from developing states in Latin America, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, where Moscow competed with both Washington and Beijing for influence. He vowed that the three nuclear powers then in Moscow should make all 130 countries in the United Nations General Assembly sign and ratify the treaty to make China’s isolation as severe as possible.

Khrushchev hoped that nonaligned Afro-Asian nations rather than Moscow or her communist allies would pillory China. When Harriman put forth a clause in which a nuclear test justified withdrawal from the treaty (an obvious reference to China’s looming detonation), Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko refused because others would interpret it as an “open admission” that the United States was applying pressure on the Soviet Union to rein in the People’s Republic. They were happy for African and Asian nations to give Mao a black eye, yet loath to be seen cheering them on against their sworn comrades.

France tested its first nuclear weapon in 1960 and tested many subsequent nuclear weapons in French Polynesia, such as this one in 1971 (left). After France tested its first nuclear weapon in the Sahara in 1960, students from Mali studying in Germany protested the testing as “the African people need no atomic bomb. [They are] living in peace and calling for the immediate end of colonial rule in Africa” (right).

Moscow was even happier for Washington to do its dirty work, and encouragement came from unexpected quarters. At a boozy reception at the Polish Embassy, Lydia Gromyko, the wife of the Soviet Foreign Minister, cornered Foy Kohler, the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, to urge him and Harriman to finalize the test ban. “We have to have this,” she said, “so that when those Chinese have their first nuclear explosion, we will have a basis on which to call them to account.

At their final meeting, Khrushchev brushed Harriman aside once more. A nuclear-armed China, he assured the American emissary, would buttress the communist world against the capitalists. When Harriman retorted that Chinese rockets might one day target Moscow, Khrushchev asked if Kennedy and Johnson also trembled at the thought of London and Paris launching nukes against Washington, D.C.

From China to North Korea

Lydia Gromyko’s slip was probably intentional. She and her husband could not have missed how insistently Harriman was pressing the China issue. It was also clear that a Chinese nuclear arsenal would unsettle U.S. relationships throughout the Asia-Pacific.

First Kennedy and then Johnson thought seriously about hitting Beijing’s nuclear facilities and missile installations, but only if China furnished them military grounds to do so. But the Kremlin would not countenance measures against China that went beyond propaganda.

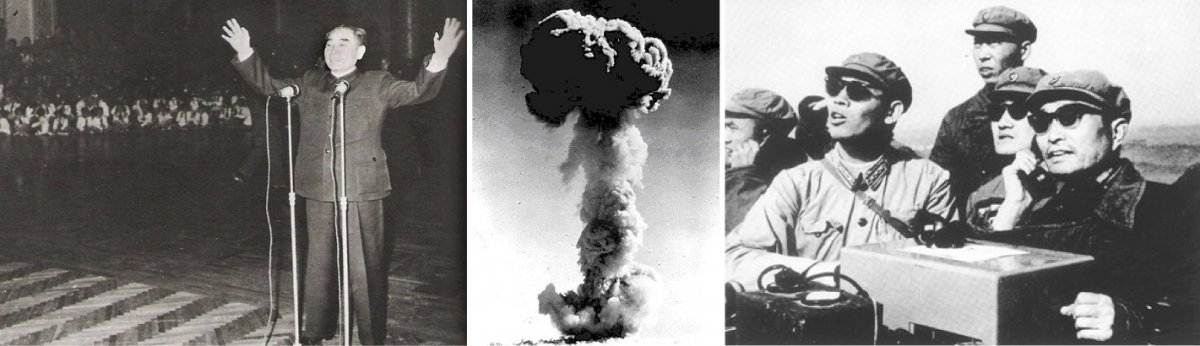

Premier Zhou Enlai announcing the successful first test of a Chinese nuclear bomb in 1964 (left). The mushroom cloud from China’s first nuclear weapon (center). General Zhang Aiping reporting the successful first detonation to Premier Enlai in 1964 (right).

China tested a nuclear bomb on October 16, 1964. That same day, Khrushchev was ousted as leader of the Soviet Union, in part because of how he had handled the Sino-Soviet split. In the end, super-power diplomacy did not prevent the People’s Republic of China from acquiring nuclear weapons.

Yet China’s bomb did jolt the U.S. government into redirecting its attention toward the arrival of atomic arsenals in new hands. When the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) on August 5, 1963, they laid the foundation of a global nuclear nonproliferation regime that internationalized efforts to slam the nuclear club’s door shut.

It was no accident that first the LTBT and then the NPT, which opened for signature in July 1968, originated at a time when decolonization was revolutionizing the international community from a pre-1945 order of empires to a postwar order of interdependent and heterogeneous nation-states.

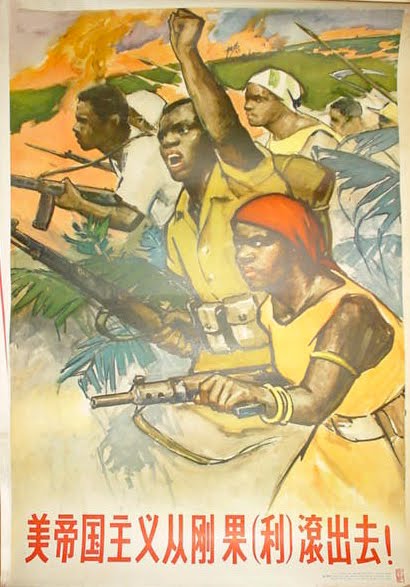

Faced with a new nuclear threat in East Asia in the form of the People’s Republic of China and the persistence of the Sino-Soviet military alliance for all Mao and Khrushchev’s venom, the United States turned to global arms treaties to harness African and Asian opinion against the next member of the nuclear club.

China’s neighbors—India, Japan, Australia, and South Korea, among many others—welcomed the LTBT on both geopolitical and humanitarian grounds in 1963. All but India also drew comfort from the U.S. nuclear umbrella they sheltered under.

So when Harriman, Hailsham, and Khrushchev put the finishing touches on the LTBT, they forged an enduring association between nuclear testing and deviant state behavior.

A map of nations’ status on the Partial Test Ban Treaty as of 2008.

They also set the foundation for a global nuclear regime whose ultimate guarantors were a U.S. nuclear arsenal that extended formally over 18 allied countries and (increasingly more since the fall of the Soviet Union) the U.S. military’s ability to police the globe.

America’s campaign to limit the spread of nuclear weapons succeeded according to its public rationale. In 1963, Kennedy warned that he saw “the possibility in the 1970s of the President of the United States having to face a world in which 15 or 20 or 25 may [have] these weapons.” Fifty-five years later, only nine nuclear powers exist.

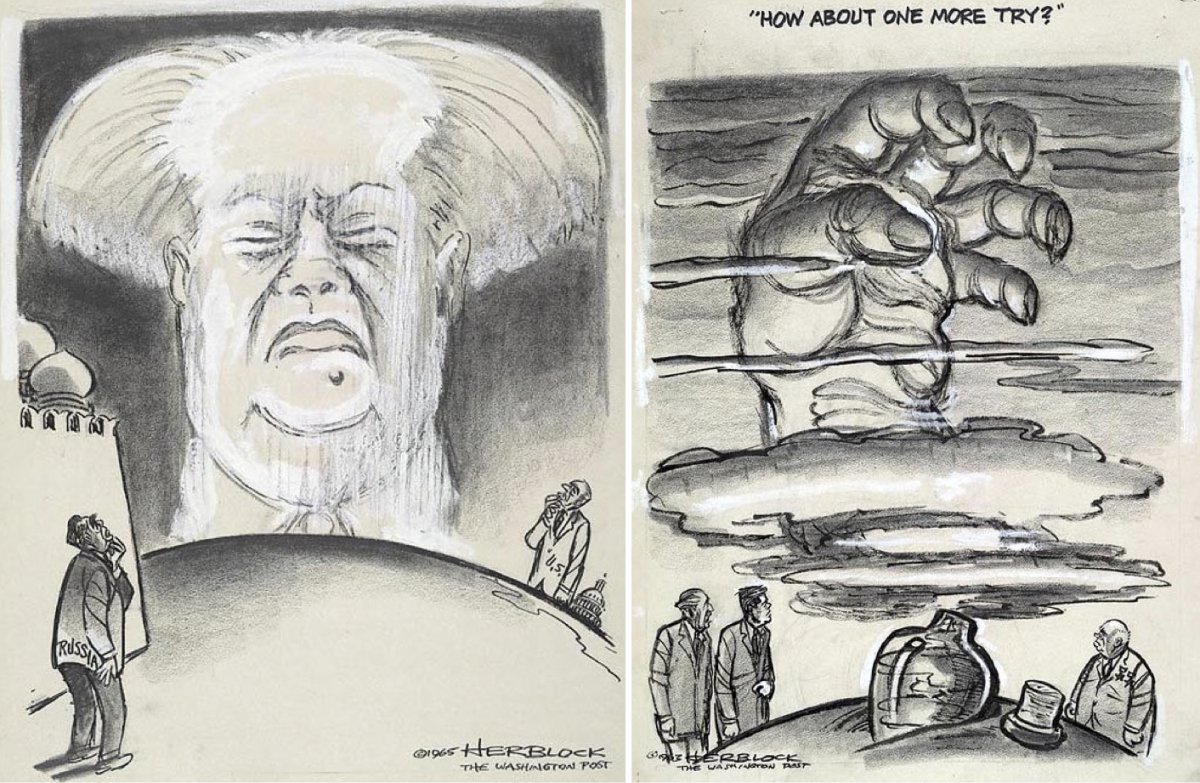

A 1965 cartoon with a mushroom cloud with a likeness of Mao Zedong rising between Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev and U.S. President Lyndon Johnson looking on anxiously. A 1965 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation (left). During negotiations for a nuclear test ban agreement, President Kennedy remarked at a press conference that if they did not act soon, “the genie [might be] out of the bottle.” This 1963 cartoon depicts this idea with President Kennedy and British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan on one side of a jar and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev on the other as a menacing hand rises between them like a mushroom cloud. A 1963 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation (right).

While Israel had surreptitiously acquired a basic nuclear capability before the ink on the NPT was dry in 1968, the treaty and its accompanying regime of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards helped the United States to halt military programs in South Korea, Taiwan, and Brazil. It delayed the arrival of nuclear arms in Indian and Pakistani hands until the late 1990s and stimulated their removal from South African, Ukrainian, Belorussian, and Kazakhstani territory after the Cold War ended.

The ends have not always justified the means by which the United States has pushed nonproliferation. The United States turned a blind eye to Israel’s nuclear arsenal as long as Tel Aviv does not test and was not “the first to introduce [them] into the Middle East.” American diplomats drafted the NPT in ways that permitted the stationing of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe and, until 1991, South Korea.

The emblem for the International Atomic Energy Agency (left). Leftover bomb casings at an abandoned nuclear bomb production facility near Pretoria, South Africa, which stopped its nuclear weapons program in 1989 and dismantled all its bombs (right).

They shaped a regime that let U.S. allies like Japan, South Korea, and European Union members possess “dual-use” nuclear capabilities—plutonium reprocessing and uranium enrichment—placing them within months of military nuclear capabilities.

Yet nonproliferation also justifies international sanctions and preventive strikes against adversaries like Syria, Iraq, or Iran who use black markets to procure equipment that a U.S.-led cartel of nuclear suppliers refuses to sell them.

President Trump and South Korean President Moon Jae-in in South Korea in 2017 (left). U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell holding a vial of anthrax during his 2003 presentation to the United Nations Security Council in the lead up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq (right).

Washington acquiesced (unhappily in President Ronald Reagan’s case) when Israel bombed nuclear reactors in Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2007. And it illegally invaded Iraq based on trumped-up intelligence that Saddam Hussein’s government had violated its NPT commitments.

The World’s Nuclear Future

These legacies remain relevant today, though for how much longer is unclear. Washington remains ostensibly committed to halting or reversing the spread of ballistic missiles and weapons of mass destruction worldwide. But 53 years separate China’s first nuclear test from the current North Korean nuclear crisis.

The two cases feature striking similarities.

The PRC and the DPRK are the communist halves of divided nations—the Republic of China sits across the Taiwan Straits and the Republic of Korea across the demilitarized zone. Both fought U.S. forces from 1950 to 1953, and aided the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in its war to reunify that nation.

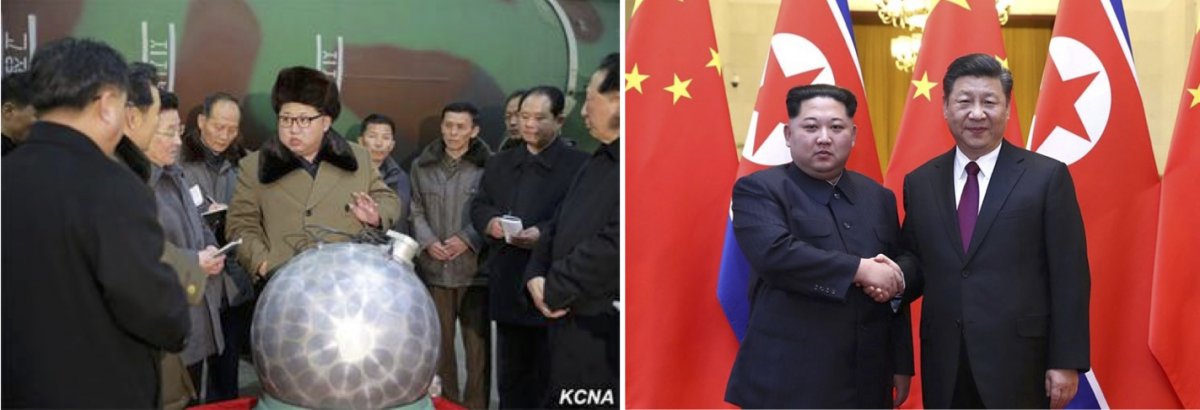

A North Korean image of Kim Jong-un supposedly with a miniaturized nuclear bomb in 2016 (left). Chinese President Xi Jinping invited Kim to China for talks in 2018 and received him with much fanfare (right).

Both counted on an ally—the Soviet Union and China, respectively—to shield them against U.S. military power in alliance with their enemy co-nationals. Their dictators—Mao Zedong and the Kim family—both fostered cults of personality that blurred the lines between the legendary and the preposterous.

For all its iconoclasm, inconsistency, and inexpertness, the Trump administration has embraced a cause that Trump once scorned—nuclear nonproliferation. What Kennedy’s administration did to avert China’s nuclearizing, and what they did not do, remain instructive amid the riskiest nuclear crisis since that in Cuba in October 1962.

Protesters in Chicago, IL in October 1962 against the Kennedy administration’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis and seeking UN involvement (left). As part of a women’s peace activist group seeking to ban nuclear testing, 800 women protested near the UN Building during the Cuban Missile Crisis (right).

While many wonder why North Korea risks war with the world’s foremost military power by so belligerently brandishing its new nuclear arms, fewer ask why the United States has assumed the mantle of judge, jury, and executioner in the court of nuclear law and order. Those answers point back a half century, when Kennedy and Khrushchev harnessed postcolonial world opinion to isolate China as it threatened Moscow’s leadership of world communism and Washington’s dominion over the Pacific.

Of the two Cold War superpowers, only the United States exists today. Yet the globe-spanning military empire that it fashioned in its geo-ideological battles with the two communist titans—a now reduced Russia and a quasi-capitalist People’s Republic of China—remain.

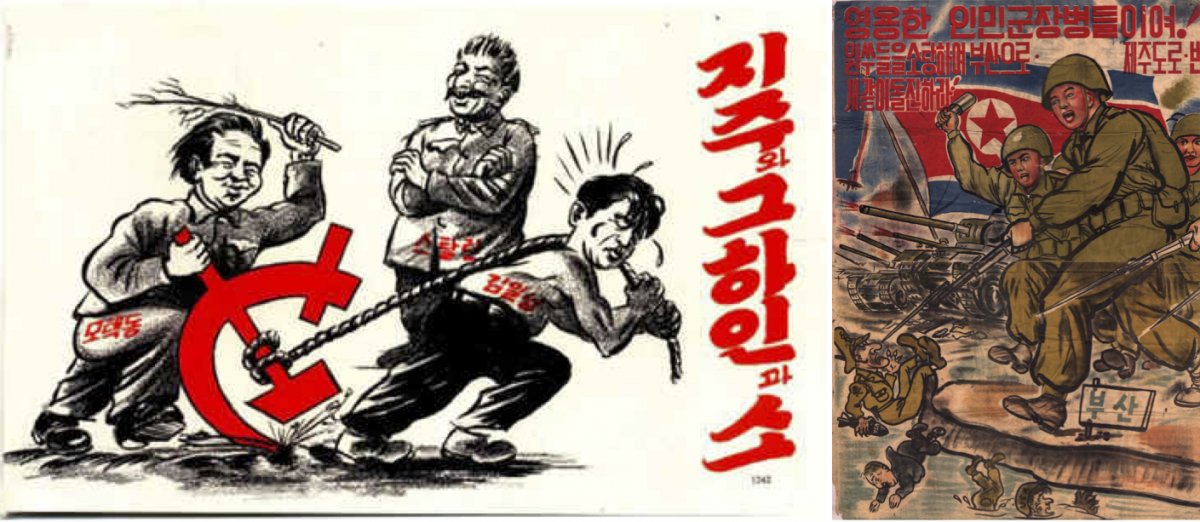

UN propaganda dropped over North Korea in 1952 in an attempt to demoralize the populace by showing them being manipulated and worked by Mao Zedong and Josef Stalin (left). A propaganda flyer from 1951 showing victory over American forces (right).

To understand why the United States treats Iran and North Korea as nuclear rogues, it is worth revisiting the time when its leader laid the foundation stones of the nonproliferation regime.

After China’s test in 1964, President Johnson would assemble a blue-ribbon committee of scientists, businessmen, and former government officials to examine the issue. They concluded that China’s nuclear capability would not pose a direct military threat to the United States for at least a decade. But the example of “a poor, backward non-white power” building the bomb would enhance “the bargaining power of backward nations” and perhaps even cause American society to “revert” to its pre-World War II “isolationism.”

In an era of Muslim bans, border walls, and “shithole countries,” it may well be that when Trump sits down with Kim, American chauvinism will cut against any impulse to enforce a common law for humanity. Or perhaps in placing “America First,” Trump will shrug off the unwritten norms and international laws that have disciplined overweening American military power since 1945.

Read more on nuclear weapons from Origins: Civil Defense and Nuclear War, Japanese Nuclear Power; Hiroshima.

Read and Listen more on North Korea and China: The United States and China; The China Dream; North Korea; The Myth of a Hermit Kingdom; China and Africa; Remembering Tiananmen; Hong Kong; Taiwan’s Politics; and The Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Alagappa, Muthiah, ed. The Long Shadow: Nuclear Weapons and Security in 21st Century Asia . Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Bundy, McGeorge. Danger and Survival: Choices about the Bomb in the First Fifty Years . New York: Random House, 1988.

Burr, William, and Jeff Richelson. “Whether to ‘Strangle the Baby in the Cradle’: The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-64.” International Security25, no. 3 (Winter 2000): 54–99.

Chang, Gordon H. “JFK, China, and the Bomb.” The Journal of American History74, no. 4 (March 1998): 1287–1310.

Chen, Jian. Mao’s China and the Cold War. The New Cold War History. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Chinoy, Mike. Meltdown: The Inside Story of the North Korean Nuclear Crisis. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2008.

El Baradei, Mohamed. The Age of Deception: Nuclear Diplomacy in Treacherous Times. New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Co, 2011.

Gavin, Francis J. Nuclear Statecraft: History and Strategy in America’s Atomic Age. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Jones, Matthew. After Hiroshima: The United States, Race, and Nuclear Weapons in Asia, 1945-1965. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Lewis, John Wilson. China Builds the Bomb. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Maddock, Shane J. Nuclear Apartheid: The Quest for American Atomic Supremacy from World War II to the Present . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Miller, Nicholas L. Stopping the Bomb: The Sources and Effectiveness of US Nonproliferation Policy . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Rubinson, Paul. Redefining Science: Scientists, the National Security State, and Nuclear Weapons in Cold War America . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016.

Sagan, Scott Douglas, and Kenneth N. Waltz. The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: An Enduring Debate. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2013.

Solingen, Etel. Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Tannenwald, Nina. The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons since 1945 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Weart, Spencer R. Nuclear Fear: A History of Images. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Wenger, Andreas. Living with Peril: Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Nuclear Weapons. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1997.