December 25, 1848, brought an unwelcome gift to the Queen City. That Christmas Day, a dying man was borne from the Lewis Wetzel, a New Orleans steamboat moored on the Ohio River. His intestines percolated with the deadly bacterium Vibrio cholerae.

On January 4, 1849, the Cincinnati Daily Gazette recorded eight additional new cholera cases, five of them fatal. The city’s Board of Health, established after the first cholera pandemic reached Cincinnati 17 years earlier, saw no “cause for apprehension or anxiety … or any reason to suppose that the dreaded pestilence is upon us as an epidemic.”

Though cholera had hit the city before, its scale in 1849 was both new and terrifying.

In 1832, it killed some 2% of Cincinnati’s roughly 30,000 inhabitants. This first global pandemic reflected new routes of transportation, commerce, and migration that allowed the disease to move more freely and rapidly. The disease itself was perhaps thousands of years old but localized to the Indian subcontinent for most of its history.

Then in 1849, Cincinnati’s weekly newspapers related cholera’s progress with concern as the disease struck from Quebec in Canada to the Great Lakes, along the Atlantic coast, and up the Mississippi to the Ohio Valley. Some 6,000 Cincinnatians would die, 5% of the city’s roughly 115,000 population.

And death, when it came, was horrific: producing voluminous discharge of rice-like white diarrhea. One physician described the tell-tale signs of cholera’s hapless victims: “countenance quite shrunk, eyes sunk, lips dark blue, as well as the skin of the lower extremities; the nails … livid.”

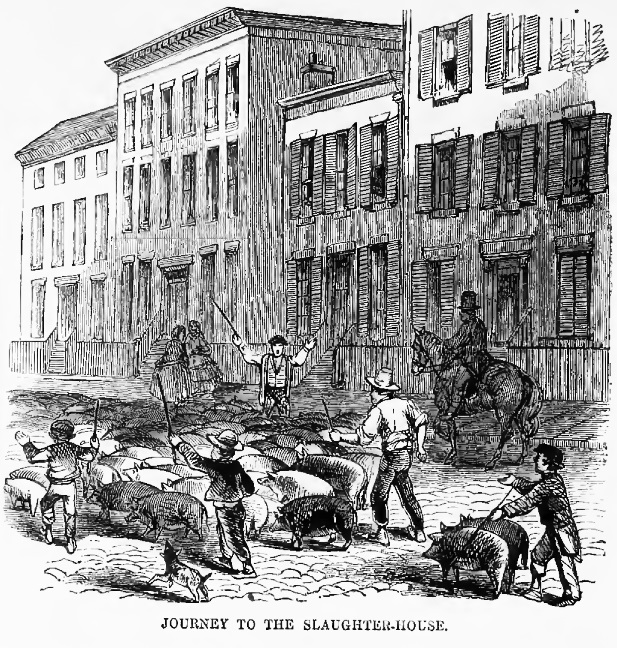

The picture "Journey to the Slaughterhouse" was first published in Harper's Weekly on February 4, 1860 (illustration courtesy of the author).

In 1849, Cincinnati was the sixth-most populous city in the United States, renowned as “the Athens of the West,” but also nicknamed “Porkopolis” after its meat processing industry. By the mid-19th century, Cincinnati slaughterhouses rounded up and butchered some half-million pigs each winter, when cold weather sufficed for refrigeration.

“Cincinnati is the city of pigs,” wrote English visitor Isabella Lucy Bird. “[S]wine lean, gaunt, and vicious looking, riot through her streets.” Though compounding the city’s squalor in many ways, these semi-feral herds served one vital end, recycling neglected mounds of garbage and human waste (pigs, unlike people, are not spreaders of Vibrio cholerae). Pigs thus constituted the most extensive public health agents in the city, but still the cholera returned.

English travel writer Isabella Lucy Bird (1831-1904) who visited Cincinnati in the 1850s.

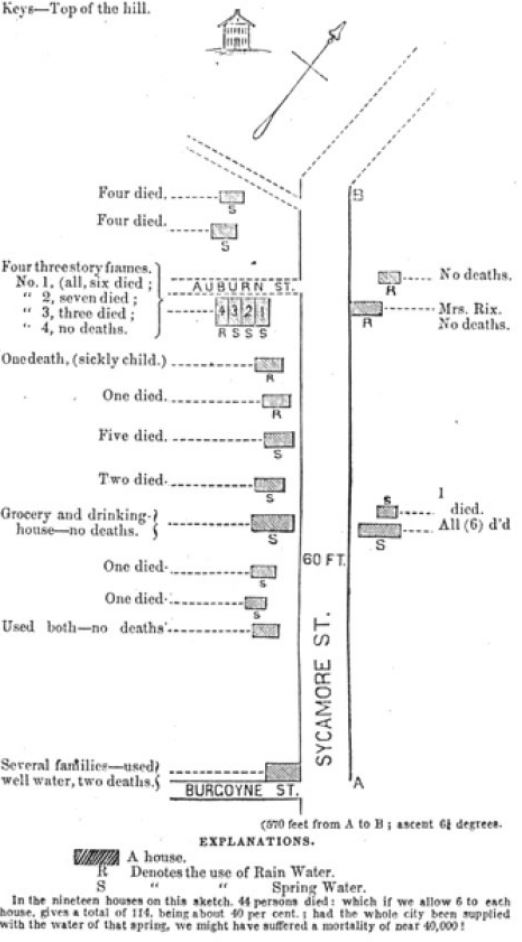

After Cincinnati’s initial December outbreak, which steadied to a trickle over spring, the cholera erupted in the humid summer of 1849. The city’s German, Irish, and black neighborhoods, blighted with appalling sanitation, suffered extreme mortality. Immigrants were 40% of the population, but according to one contemporary source four times likelier to die than native-born Americans.

Nativist politicians blamed everything from intemperance to crime and prostitution on this “plague of strangers.” Epidemic disease became one more crisis blamed on someone else. In July 1849, one Cincinnatian wrote his wife that 130 fellow citizens had perished the previous day. “But do not be alarmed,” he shrugged. “They are mostly German and Irish. Very few whom we knew have died.”

Today, COVID-19 tests public confidence in politics, medicine, and news journalism, but during the cholera pandemic of 1849, things looked even shakier.

In August 1849, President Zachary Taylor declared a national day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer, but responsibility for public health devolved to state and local hands. The previous month, Cincinnati Mayor Henry E. Spencer likewise announced a day of fasting and humiliation at the behest of local Protestant ministers, but little else to tackle the cholera head-on.

In 1849, Cincinnati failed to deliver basic public health services taken for granted today. An article in the June 1, 1819 Inquisitor and Cincinnati Advertiser decried the city’s streets as a “cinque [sic] of pestilence and disease,” and called on the newly-chartered city government to act. Some thirty years later, the city’s population had more than tripled and its unpaved streets remained a civic embarrassment.

A September 13, 1848 editorial from the Daily Gazette complained the city was “looked upon, and with much truth, as the dirtiest city of its kind in the Union. Some of the gutters in the principal streets are so offensive to the eye and nose as to make a walk along them disgusting.”

Although Cincinnati employed some human scavengers to remove detritus, mostly around the central marketplace, city streets were typically abandoned to private neglect and the scavenging of hogs. Disposal of human and animal waste remained a lasting problem. The first municipal sewer district was not established until 1864, and even today, Cincinnati’s sewerage remains notoriously antiquated.

Like cholera in the nineteenth century, COVID-19 is a scourge of modernity, reflecting unprecedented levels of human density and mobility. Cincinnati built its prosperity on the flourishing river trade between New Orleans and Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), but this same route of commerce also brought the first cases of cholera.

Through the 1840s, the Queen City remained the boomtown of the Midwest, vaunted by boosters including one who proclaimed in 1841 “that within one hundred years … Cincinnati will be the greatest city in America; and by the year of our lord two thousand, the greatest city in the world.”

Cholera dampened such optimism in 1849.

A steel engraving showing Cincinnati in 1872 as a heavily industrialized city.

The following year, an estimated 10,000 pandemic “fugitives” failed to return for the city’s census, after fleeing in “every vehicle and conveyance” from the city and “its suburbs and immediate adjacencies.” Though Cincinnati recovered demographically, the scars of the epidemic endured.

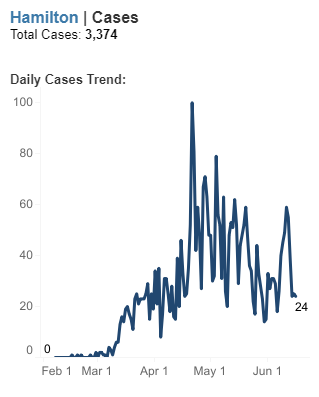

On March 19, 2020, Hamilton County, Ohio, where Cincinnati is located, confirmed its first cases of COVID-19 coronavirus, a woman in her twenties and a man in his sixties, within two hours of each other.

The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that the man was hospitalized in intensive care, while the woman was quarantined with family in the Cincinnati area. The county medical director sounded a bit like the Board of Health in 1849, declaring: “Hopefully, she has recovered. Today, she looks pretty good. She’s had a rough four or five days of it, sitting on her bed basically on her laptop doing work.”

Today Cincinnati ranks just 64th by population among incorporated cities in the United States. The human toll of coronavirus on Cincinnati, though dreadful, is familiar. Harder to predict will be the economic and cultural costs in this moment of lockdown, anxiety, and virtual isolation.

In 2020, as Cincinnatians converge downtown in facemasks, protesting racial injustice, the tension is striking. However bravely Cincinnati weathers COVID-19, only time will tell how the life of the city returns, or if coronavirus portends greater challenges to come.