This summer marked significant progress in resolving one of the longest running guerrilla insurgencies in Latin America when the Colombian government signed a cease-fire agreement with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, known to the world as the FARC. While the conflict between the FARC and successive Colombian governments has been going on for decades, this month Steven Taylor describes how the FARC grew out of earlier periods of political violence stretching back in the 19th century and the many reasons why peace has been an elusive goal.

On June 23, 2016, while most of the world was awaiting the outcome of the Brexit vote, another major historical event was taking place in Havana, Cuba. At a meeting hosted by President Raúl Castro and overseen by UN General Secretary Ban-Ki Moon, Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos and the supreme commander of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, Fuerzas Armada Revolucionarios de Colombia), Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri (a.k.a. Timochenko), signed an accord for a ceasefire in a multi-decade armed conflict.

While not the final act in the peace process, the pact was essential to guarantee the success of the negotiations. The government and the guerrillas are now poised to sign the entire agreement on September 26, 2016, in Cartagena that will then be voted on in a national plebiscite.

The FARC is the largest guerrilla group in Colombia and one of the longest continuously active such groups in the world. It is part of long-term political violence in the second most populous country in South America. Its demobilization constitutes a major shift in the political history of that republic.

Colombians marching against FARC kidnappings in 2008.

It was founded in 1964 and has been in continuous operation. Numerous attempts at a negotiated peace have come and gone, but none has ever come as far as the current process. While there are significant obstacles to a lasting peace, it does appear that Colombia is approaching a new era.

Political Violence and Violent Politics: Colombia’s History

Political violence has been a mainstay of Colombian historical and political development.

The nineteenth century was one of civil wars over the basic rules of political activity in Colombia, such as whether the country should be ruled in a unitary or federal fashion, as well as over such issues as the role of the Catholic Church and the appropriate economic development model.

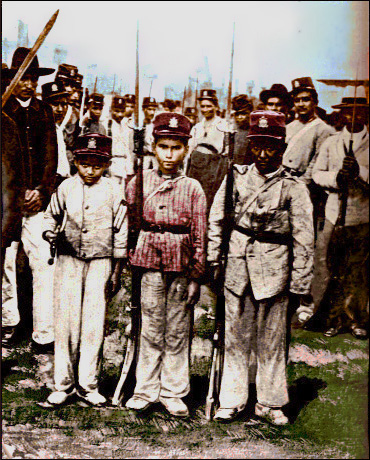

|

| Three child soldiers during the War of a Thousand Days (1898-1902). |

Between 1821 and 1886, Colombia had eight constitutions, each born via violence (usually a full-blown civil war). The 1886 constitution, however, ended the cycle and remained in force until 1991.

That constitution, though, did not end the political violence. There would still be the War of a Thousand Days (1899-1902), various peasant uprisings in the 1920s and 1930s, and the infamous La Violencia (1948-1953 or later, depending on how one marks that conflict).

Periods of protracted peace are the aberration in Colombia’s history, not the other way around. Political activity and establishment of the rule of law have long been associated with violence in Colombia. One factor that led to the War of a Thousand Days was the question of how to structure electoral rules. And until the late 1950s, the most violent clashes were between the traditional political parties (Liberals and Conservatives).

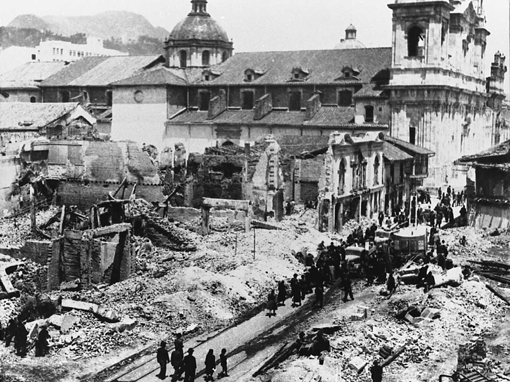

The aftermath of a riot in Santa Fe de Bogotá in 1948.

It is also in this context that an odd paradox of Colombian political development should be noted: despite the significant levels of political violence that the country has experienced over time, it has not suffered the military governments that most of its Latin American neighbors have endured. Indeed, coups have been rare in Colombia and the only military government of the twentieth century was the relatively brief rule of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla from 1953-1957.

Peasant violence in the 1920s and 1930s over issues of land distribution and La Violencia in the 1940s and 1950s are most significant to understanding the origins of the FARC and appreciating the significance of a final peace deal with that group.

From the early 1920s to the mid-1930s, there were a number of peasant protests, notably in the coffee producing regions of Sumapaz and Tequendama. There, the Communist Party of Colombia played an active role. Factions of the party would later contribute to the creation of the FARC.

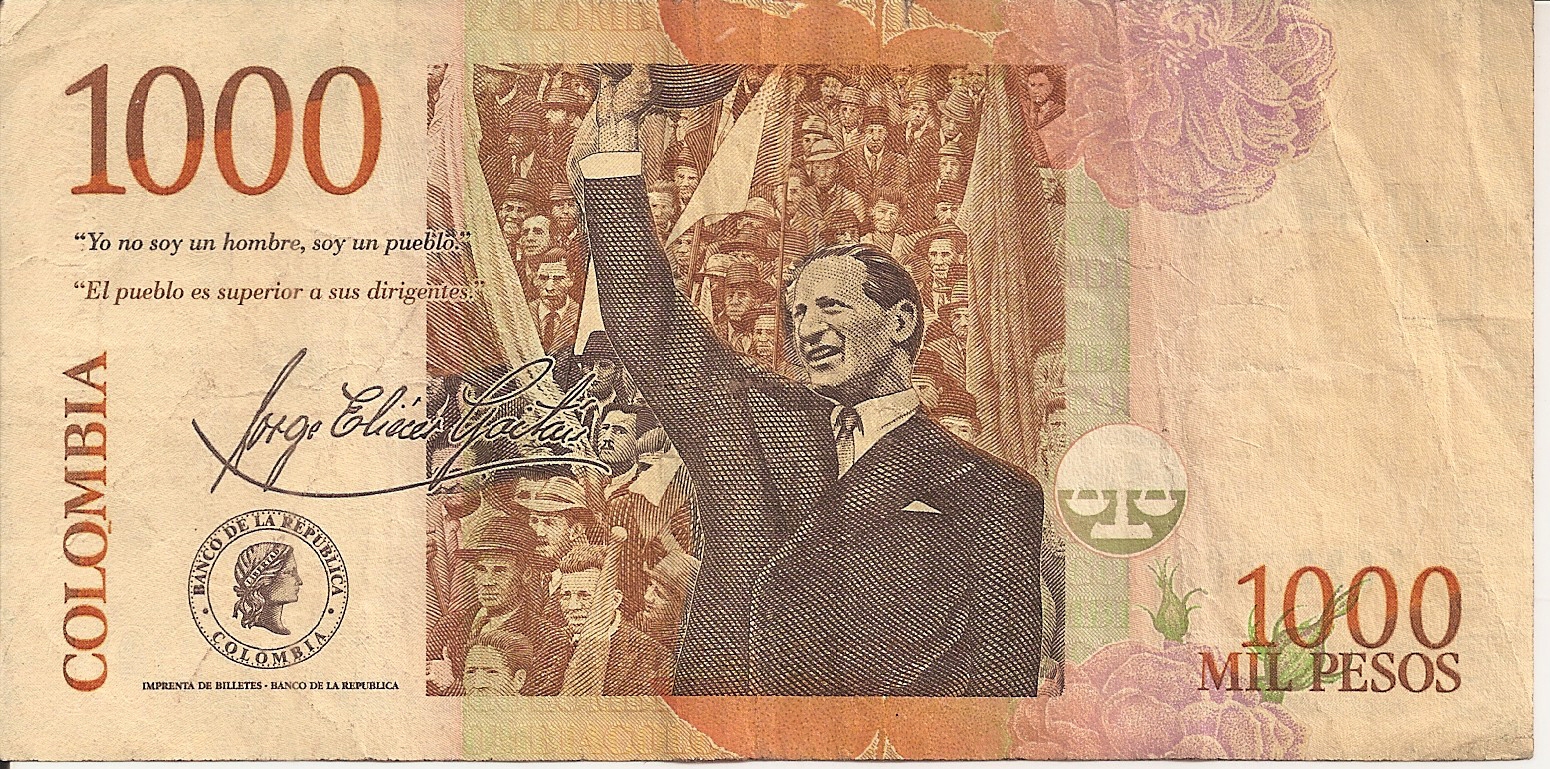

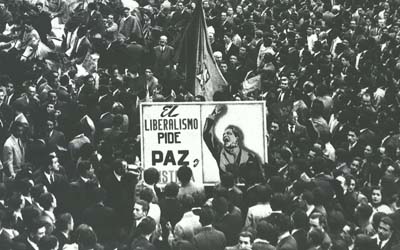

An even clearer antecedent to the formation of the FARC are the events of the later 1940s. On April 9, 1948, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a lawyer, progressive politician, and likely future president of Colombia, was murdered on the streets of Bogotá in front of his law offices. The murder itself was likely apolitical (indeed, no clear motive has ever been discerned and the alleged murderer was killed by a mob). However, the widespread perception that Gaitán had been assassinated by political rivals sparked the urban riot known as the bogotazo, which helped accelerate and deepen existing rural violence.

This conflagration would blossom into a full-blown civil war called La Violencia that would lead to 200,000 deaths (estimates range from 80,000-400,000). The lines in this conflict were drawn between Conservative and Liberal Party adherents, a division that had driven the civil wars of the previous century.

Conflict between the parties is relevant to the formation of the FARC in several ways. First, some of the Liberal insurgents in this era had connections with the Communist Party of Colombia. Second, and more specifically, one of these peasant fighters was a man named Pedro Antonio Marín, who would earn the nickname tirofijo (“sure shot”) and later adopt the nom de guerre Manuel Marulanda Vélez, founder and longtime leader of the FARC.

|

| Riots in Bogotá in April 1948 engulf a trolley car in Bolívar Square. |

Third, when La Violencia led to the Rojas coup in 1953, the military regime offered amnesty to Liberal and Conservative insurgents but banned the Communist Party. This led to military actions against segments of the peasantry, which formed self-defense groups.

Finally, the peace accord that the Liberals and Conservatives would eventually strike, a power-sharing agreement called the National Front, would serve as a raison d’être for guerrilla activity by many anti-government groups in Colombia in the 1960s.

The Liberal and Conservative parties were able to settle their differences via negotiations, which prompted the ouster of Rojas and the restoration of civilian rule. A 1957 referendum installed the National Front power-sharing agreement that would last until 1974. It created an alternation of the presidency between the Liberal and Conservative parties and effectively split governance in half: each party would get half the seats in congress, departmental assemblies, and municipal councils.

This parity provision extended to appointed positions, such as the cabinet, governors, and mayors (local executives were not popularly elected at the time). This system was seen as exclusionary by the Colombian left and a continuation of the long-term oligarchic tendencies of Colombian economics and politics. While the system was more open to political competition than a brief description can provide, there is no doubt that the system favored existing parties in numerous ways.

In the wake of the successful Cuban revolution and the general global movement toward radicalization of the left in the developing world, it is not surprising that numerous Marxist guerrilla groups emerged in this era, and that the rules favoring the traditional parties were one of numerous justifications laid out to explain their activities.

It is in this context that the FARC was born in the 1960s.

It was one among several rural guerrilla groups, including the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional/National Liberation Army), and the EPL (Ejército Popular de Liberación/Popular Liberation Army). Others would also emerge, but these were the most significant over the next several decades, along with the urban group the M-19 (Movimiento 19 de Abril/Movement of April the 19th), which would emerge after allegations of electoral fraud in the 1970 presidential elections.

The FARC, then, was one group among many, and in the 1970s and into the 1980s, the M-19 would arguably be the most significant. M-19 and EPL would demobilize in conjunction with the process of writing the 1991 constitution. The ELN persists to this day alongside the FARC and they are in the early stages of a peace process with the Colombian government.

A History of Failed Peace Initiatives, Persistence, and Growth

|

| FARC’s areas of operation c. early 2000s. |

The FARC’s stated goal was to defeat the oligarchy that it saw as formed by the Conservative and Liberal Parties and to overthrow the state they controlled. They operated primarily in the rural zones, often fulfilling local governing functions that the Colombian state was failing to accomplish.

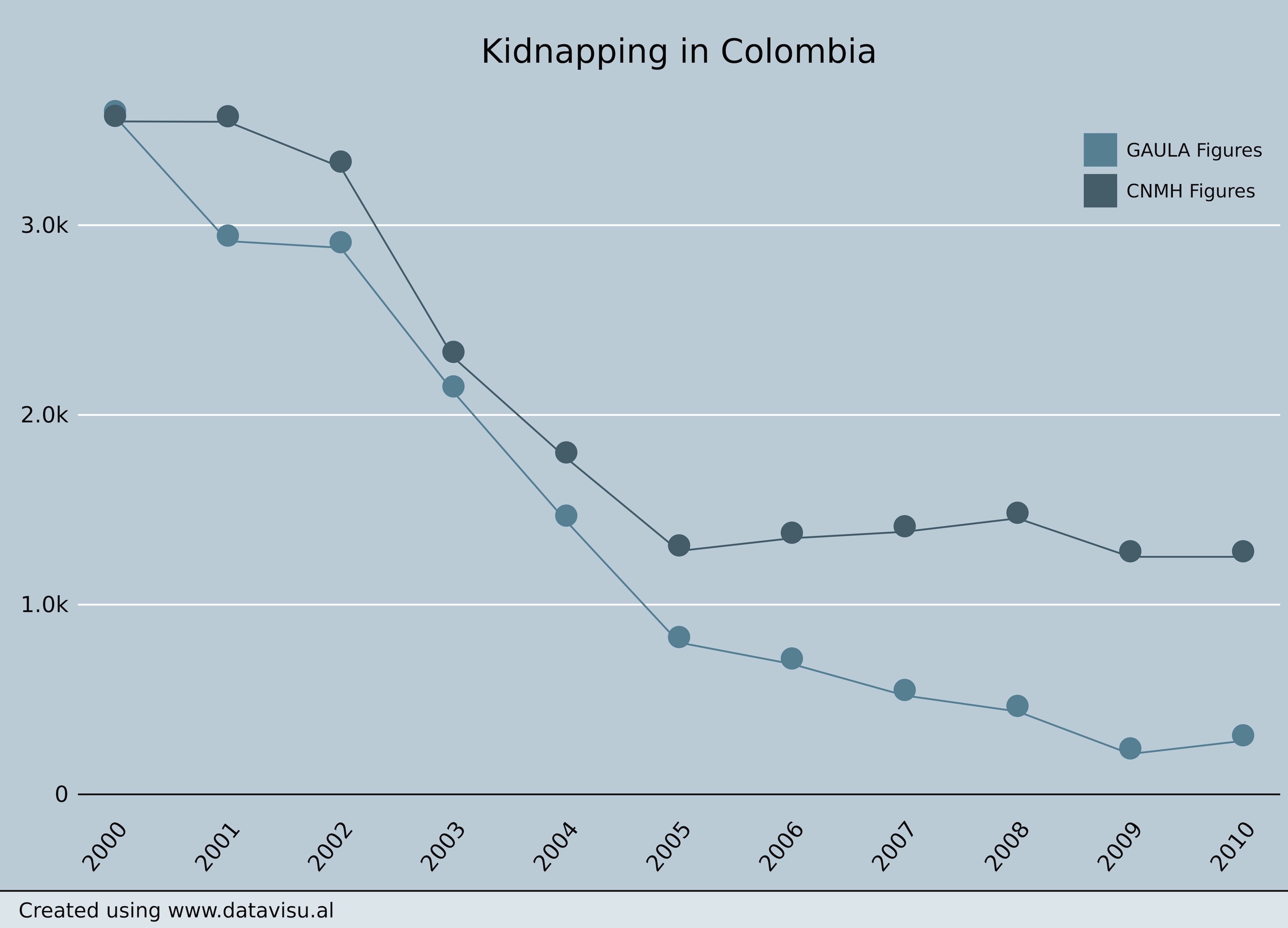

They would attack military installations as well as state and economic infrastructure. Landowners and other elites were often the focus of extortion and robbery. Over time, the FARC became heavily reliant on kidnapping as both a source of revenue as well as a means of making political statements. In the later decades, they often also staged urban attacks, such as car bombings and mortar attacks on police and military locations.

The 1970s was a period of growth for the FARC from roughly 500 fighters to an estimated 3,000 by the early 1980s. In 1982, the group’s Seventh Conference led to a name change, with the group officially becoming the FARC-EP (EP for Ejército Popular, or People’s Army).

The group also decided that taxing the cocaine trade was a legitimate method of funding its activities. They began levying “taxes” on coca producers and drug trafficking routes and eventually became active participants in the drug trade itself.

The 1980s also saw the first significant attempt at a negotiated peace. Talks with the Belasario Betancur administration (1982-1986) led to the La Uribe agreement in 1984 that included a ceasefire. That agreement contributed to the formation of a new political party, the Patriotic Union (UP/Unión Patriótica), which became an electoral vehicle for the Colombian left that had been excluded in the Liberal-Conservative power sharing arrangements.

The UP successfully found a niche in Colombian politics, albeit a small one. It was able to win a number of mayoralties (an office that became popularly elected in 1988) as well as seats in Congress. However, right-wing paramilitary violence soon was systematically aimed at the party and its allies.

The flag of the Patriotic Union (UP). Right-wing paramilitary violence against the UP left thousands of supporters dead (Left). A FARC car bomb attack at the Caracol Radio headquarters in 2010 (Right).

In 1987, early in the party’s existence, 450 adherents were murdered by various paramilitary actors in a pattern that would continue for years. Drive-by assassins on motorcycles gunned down individuals in front of their homes or in their offices or cars, attacks that continued successfully even with heightened security.

By 2004, the estimated number of UP affiliates killed by paramilitary violence was over 3,000. This experience made further peace talks more difficult and is relevant even now as the FARC negotiates to return to civilian politics given that many of the armed combatants left have not forgotten what happened the last time peace talks promised a transition to peaceful, civilian politics.

Indeed, while many Colombians oppose the peace talks on the grounds that the Colombian state is offering impunity to the guerrillas, many in the FARC see the state and its allies likewise escaping justice for past crimes. Additionally, Colombia’s history of violence means that many in a demobilized FARC will believe themselves vulnerable to attacks by those who oppose the peace accords.

Over the long haul, the experience of the UP has been a stumbling block for peace as many fighters have preferred to take their chances armed and in the countryside rather than in a more vulnerable civilian context.

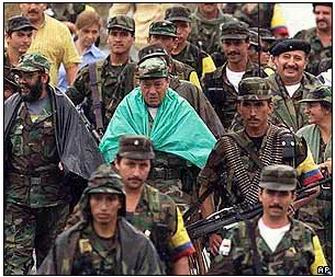

FARC soldiers with a kidnapped member of Congress in 2002. (Photo by InSight Crime).

By 1995, the FARC was estimated to have as many as 20,000 troops. Their annual income by the end of the 1990s had grown to a remarkable $900 million primarily through narcotrafficking and kidnapping for ransom. Obtaining hard numbers of this type is always difficult, but the Colombian government estimated roughly $400 million from the drug trade and another $500 million from extortion, kidnapping, and other criminal activities by 1999.

The most significant attempt at peace prior to the current process came during the administration of Andrés Pastrana (1998-2002). Pastrana’s government ceded to the FARC an area of the Colombian countryside roughly the size of Switzerland as a means of drawing the FARC into a demilitarized zone for peace talks. Pastrana himself even held direct talks with Marín.

|

| FARC soldiers during peace talks from 1998 to 2002. |

However, this process halted in 2002 after the FARC hijacked a plane carrying Senator Jorge Gechen Turbay, president of the Senate’s peace commission. Pastrana sent in the military to retake the demilitarized zone and the peace process ended in dramatic fashion after over three years of talks.

Álvaro Uribe ran for the presidency in 2002 on an explicitly anti-FARC platform and promised to increase the fight against the guerrillas in the countryside. Uribe’s father had been killed in 1983 as part of a kidnapping attempt. He himself was the target of an assassination attempt during the 2002 campaign, and his August 2002 inauguration was greeted with a nearby mortar attack by the FARC that killed 14 people.

The 2007 arrest of Luis Hernando Gomez-Bustamante, a leader of the Norte Valle Colombian drug cartel (Left). Secretary of State Colin Powell visiting Colombia in 2003 (Right).

While there were some attempts at peace talks early in the Uribe administration, government interactions with the FARC during his two terms in office were marked by military campaigns such as Plan Patriota and his general “democratic security” policies that focused on the military defeat of the FARC.

It should be noted that Uribe’s approach to the FARC was rooted in the post-9/11 War on Terror paradigm established by the George W. Bush administration. Indeed, U.S. policy in this period redefined the Colombian state’s fight against the guerrillas as fitting under the umbrella of fighting terrorism, a shift from previous administrations.

This change in approach is well illustrated by the juxtaposition of ambassadorial statements made in 1997 with those just a few years later in 2002. In a 1997 cable, Ambassador Myles Frechette categorically stated that there would be “no U.S. government assistance for fighting the guerrillas,” while Ambassador Anne Patterson stated in 2002 that the “fight against narcotrafficking and terrorism … have become one.”

Presidents George W. Bush and Álvaro Uribe at the White House in 2007.

Frechette’s position reflected a longstanding pre-9/11 view by U.S. policy-makers that the Colombian state’s fight with various guerrilla groups was an internal political matter, but that the war on drugs was about international crime. After 9/11, however, it became far more common for President Uribe to refer to the FARC and other violent actors as “terrorists” (and for U.S. attitudes to reflect this description).

The Tide Turns

If the early part of the first decade of the twenty-first century was the peak for the FARC, the latter portion of that decade would see a substantial reversal.

The year 2007 started a series of events that clearly weakened the group and set the stage for peace talks, specifically several high-profile escapes by FARC hostages and a number of public relations blunders by the group.

However, it was 2008 when the ground truly shifted. First, early February saw large anti-FARC protests in Bogotá and 100 other cities worldwide. The protests were promoted via a Facebook group called “One Million Voices Against the FARC” and included events in places such as Caracas, New York, Paris, and Washington, D.C.

In March 2008, the Colombian military struck a FARC base just over the border in Ecuador, killing one of its key leaders, secretariat member Raúl Reyes, and capturing a great deal of intelligence. Two other members of the secretariat died later that month. Iván Rios was killed by one of his own men (hoping for a government reward), and then the group’s founder, Pedro Antonio Marín, died of a heart attack. In July the Colombian military rescued Ingrid Betancourt, three U.S. contractors, and numerous others from FARC captivity without firing a shot.

Without a doubt, February to July 2008 was the most difficult stretch in the FARC’s history and clearly contributed to the willingness of the group to talk.

|

| Pedro Antonio Marín allegedly hiding out before his death in Venezuela. |

Over the next several years, a number of key leaders were killed, including two more of the secretariat: El Mono Jojoy in 2010 and Alfonso Cano in 2011. It is difficult to overstate the number of setbacks the group endured from 2007 to 2011, only a few years after its seeming apotheosis around the turn of the twenty-first century.

The Current Peace Process

Juan Manuel Santos was elected to his first term as president of Colombia in June 2010. He came to office from a prominent Liberal family, although he would be elected as a member of the National Social Union Party. His most significant résumé line was his service as defense minister (2006-2009) in the administration of Álvaro Uribe. During this time the Colombian government was pressing the FARC hard and scored a number of victories against the rebels (some noted above).

Santos did not come to office as a dove. Nonetheless, he started secretly reaching out to the guerrillas only a few months into his first term. These back-channel offers to talk led to preliminary meetings in Colombia and Venezuela before secret talks were fully initiated in Havana.

With the help of Cuban and Norwegian facilitators, an agreement between the FARC and the Colombian government was signed on August 26, 2012. Santos formally announced the beginning of these talks to the public in an address given on September 4.

The multi-year process focused on six substantive areas: land reform, political participation, end of conflict, illegal drugs, victims’ rights, and implementation.

Land reform was the first item settled, fittingly since the issue harkens back to the peasant uprisings of the 1920s and 1930s. This agreement promised redistribution of several million hectares of land to landless peasants, displaced persons, and decommissioned combatants. The accord was signed on May 26, 2013, roughly eight months into the process.

| FARC soldiers marching in 1998. |

It would be almost another year before the next accord would be signed, on the matter of illegal drugs, on May 16, 2014. This accord focused on crop substitution, public heath, and drug prevention as well as an agreement by the guerrillas to swear off the narcotics business. Exactly one year later, the accord on political participation was signed, focusing on the transition of the guerrillas to electoral politics.

A December 15, 2015 accord on victims’ rights and transitional justice created a “Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparation and Non-Repetition.” This agreement was a watershed as it was the most difficult issue to address before the ceasefire could be negotiated.

The accord on a formal end of the conflict was supposed to be signed in March 2016, but negotiations dragged into June. Its completion was a major breakthrough that signaled that the negotiations, at least, were nearing their conclusion.

Politically this has not been easy, for as much as the generic idea of peace is favored in Colombian society, there is a great deal of disagreement as to what such a peace should look like, or how it should be established. Santos’ predecessor and former boss sees the current peace process as a “capitulation” to the FARC and frequently states that it is endorsement of impunity rather than a pathway to justice.

Indeed, in the 2014 electoral cycle, Uribe formed his own party, the Democratic Center, and headed an electoral list for the Senate, winning a substantial number of seats. His main purpose in running was opposition to the Santos peace plan.

Later that year (Colombian legislative elections are in March and the first round of the presidential contests are in May), Uribe backed another former cabinet member, Óscar Zuluaga, for president. Zuluaga came in first in the first round and Santos second. This set up a run-off between Zuluaga’s anti-peace process coalition (to include Conservatives) against Santos and his pro-peace process allies. Santos prevailed with just over 50% of the vote, but continued to face uribista opposition in the Congress (i.e., those allied with the Uribe faction).

Going Forward

The stakes for peace are high.

The Colombian conflict with FARC that started in the 1960s has resulted in an estimated death-toll of 220,000 and one of the largest internal displacement crises in the world (close to 6 million Colombians). It made things like bombings and kidnappings commonplace and diverted substantial state resources to security and away from education, infrastructure, and development. The suffering in the rural zones of the country, where most of the fighting between the FARC and the armed forces has taken place, has been especially acute.

Santos promised that a final deal would be in place by July 20 of this year (Colombia’s Independence Day), but the final signing date has now been set for September 26.

Once the signing takes place, the next major step will be a plebiscite on acceptance scheduled for October 2. This step was approved by Colombia’s Constitutional Court in mid-July. The Court ruled that at least 13% of eligible voters (approximately 4.5 million people), would have to agree with the accords for the decision to be binding. Santos is taking this agreement to the population as a means of achieving legitimacy for the outcome.

Between general skepticism in large parts of the populace and the uribista opposition, it is unclear how the plebiscite vote will play out. For one thing, Santos’ own approval ratings are poor, with various polls taken in July and August placing it anywhere from 20% to 29%.

In regards to the plebiscite itself, a poll from Datexco published on August 24 in the Colombian daily El Tiempo showed the Yes position at 32.1% and the No position at 29.9%, with 9.7% not having a position and another 26.9% stating they would not vote. This poll further indicated that the final tally would have Yes edging No 51.8% to 48.2% if the undecided and abstainers were removed.

It is unclear what will happen if the result of the vote is No. It could mean renegotiation or continuation of the process without public support, a politically difficult option for Santos.

|

| Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta meeting with Colombian Special Forces in 2012. |

Public skepticism is exacerbated by the length of time this process has taken. President Santos originally projected that a deal could be reached by the end of 2013, but negotiations over the last several accords have taken far longer. In general, it is also fair to note that not only have numerous past processes failed, but the very longevity of the conflict makes it difficult for the general population to believe an end is in sight.

The uribistas are actively campaigning against approval, with Uribe himself stating that “We can only say yes to peace by voting no to the plebiscite.” He and his political allies are focused both on depressing voter turnout (due to the terms dictated by the constitution court) as well as for a “no” outcome.

So while there are reasons to be optimistic that the outcome will be a binding, lasting deal with the FARC, the politics of the moment dictate a close contest.

As anyone who has studied Colombia knows, it is a complex place and concepts such as peace are not going to be easily defined, let alone attained. Even if the process with the FARC is flawlessly executed, it will not mean the end of organized violence. The ELN remains active and there is substantial violence connected to drug trafficking and other crime.

Further, while the major paramilitary groups of the later 1990s and early 2000s have been disbanded, some of them live on as smaller regional groups that fall, along with some drug groups, under the label “bandas criminales” or bacrim.

|

| The Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá, a right wing paramilitary group opposed to the FARC. |

The good news about the ELN is that the process with the FARC has inspired talks with the government. In March 2016 it was announced that two years of preliminary talks had led to an agreement on formal talks. It does, therefore, appear that Colombia’s guerrilla war may be coming to conclusion.

Assuming that the final stages of negotiations are successful, and assuming that the “yes” vote can win at the ballot box, there remain formidable challenges. There is the issue of following through on transitional justice, evolving the FARC into a political party (or parties), and extending the presence of the state into the Colombian countryside.

There is also the fact that it is likely that some rump of the FARC will not cooperate with the process either due to political conviction or, more likely, because of lucrative criminal opportunities that will remain available. Whether such a scenario resembles Peru where Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) continue to nominally exist as a drug trafficking organization or whether former members of the FARC abandon the name and become part of the bacrim umbrella remains to be seen.

Read and Listen to Origins for more on Latin America: Cuba and the U.S. Reengage; Inflation and Argentina; Rethinking Cuba Libre; Global Migration and the Americas; Latin American Drug Trafficking; Brazil’s Elections; Brazilian Politics; Anti-Americanism in Latin America; Mexico City; and The Guatemala Inoculation Experiments

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: The FARC: A Road to Rebellion

Bagley, Bruce M. and Jonathan D. Rosen, eds. 2015. Colombia’s Political Economy at the Outset of the Twenty-First Century. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Carroll, Leah Anne. 2011. Violent Democratization: Social Movements, Elites, and Politics in Colombia’s Rural War Zones, 1984-2008. South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press.

Dudley, Steven. Walking Ghosts: Murder and Guerrilla Politics in Colombia. New York. Routledge. 2004.

LaRosa, Michael J. and Germán R. Mejía. 2013. Colombia: A Concise Contemporary History., Updated Edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Leech, Garry. The FARC: The Longest Insurgency. London: Zed Books, 2011.

Palacios, Marco. 2006. Between Legitimacy and Violence: A History of Colombia, 1875-2002. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ramírez, María Clemencia. 2011. Between the Guerrillas and the State: The Cocalero Movement, Citizenship, and Identity in the Colombian Amazon. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Richani, Nazih. 2002. Systems of Violence: The Political Economy of War and Peace in Colombia. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Rojas, Cristina and Judy Meltzer, eds. 2005. Elusive Peace: International, National and Local Dimensions of Conflict in Colombia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Welna, Christopher and Gustavo Gallón , eds. 2007. Peace, Democracy, and Human Rights in Colombia. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Online Resources

Alto Comisionado para la Paz www.altocomisionadoparalapaz.gov.co/

Brodzinsky, Sibylla. 2016. “Colombia on the brink of peace: Why is it such a hard sell to citizens?” The Christian Science Monitor. (June 23). http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Americas/2016/0623/Colombia-on-the-brink-of-peace-Why-is-it-such-a-hard-sell-to-citizens

McDermott, Jeremy. 2013. The FARC, the Peace Process and the Potential Criminalisation of the Guerrillas. InSight Crime. (May). http://www.insightcrime.org/images/PDFs/2016/farc_peace_crime.pdf

WOLA’s Colombia Peace site http://colombiapeace.org/