On October 6, 1973, the Yom Kippur War erupted in the Middle East when Anwar Sadat’s Egypt and Hafez al-Assad’s Syria launched a joint attack on Israel’s southern and northern borders. As the war progressed, Arab states in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) deployed the “oil weapon” against Israel’s allies, imposing an embargo against any nation aiding Israel.

The embargo, lasting from October 1973 to March 1974, targeted Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Rhodesia, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It and the broader Yom Kippur War further inflamed Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union while also threatening the global economy.

Before the war’s outbreak, Israel and its Arab neighbors had been at war for twenty-five years. The Arab nations adopted a strict policy against Israel based on the “three no’s”: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel. These policies, along with failed international mediation, made peace impossible.

During the Six-Day War of 1967, Egypt lost the Sinai Peninsula to Israel and Syria forfeited the Golan Heights. Both nations desired to retake these locations.

Egypt and Syria chose the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur to launch their attack against Israel, catching the nation off guard. The Arab nations aimed to recapture key territories and force a settlement through international mediation.

As the war heated up, the United States, under the Nixon administration, found itself in a difficult position. Since its establishment in 1948, Israel had emerged as a critical player in the Middle East, one that the United States could rely on for support. Failure to aid Israel threatened to alienate a key ally, while supporting the young nation would incur the wrath of both the Arab nations and the Soviet Union.

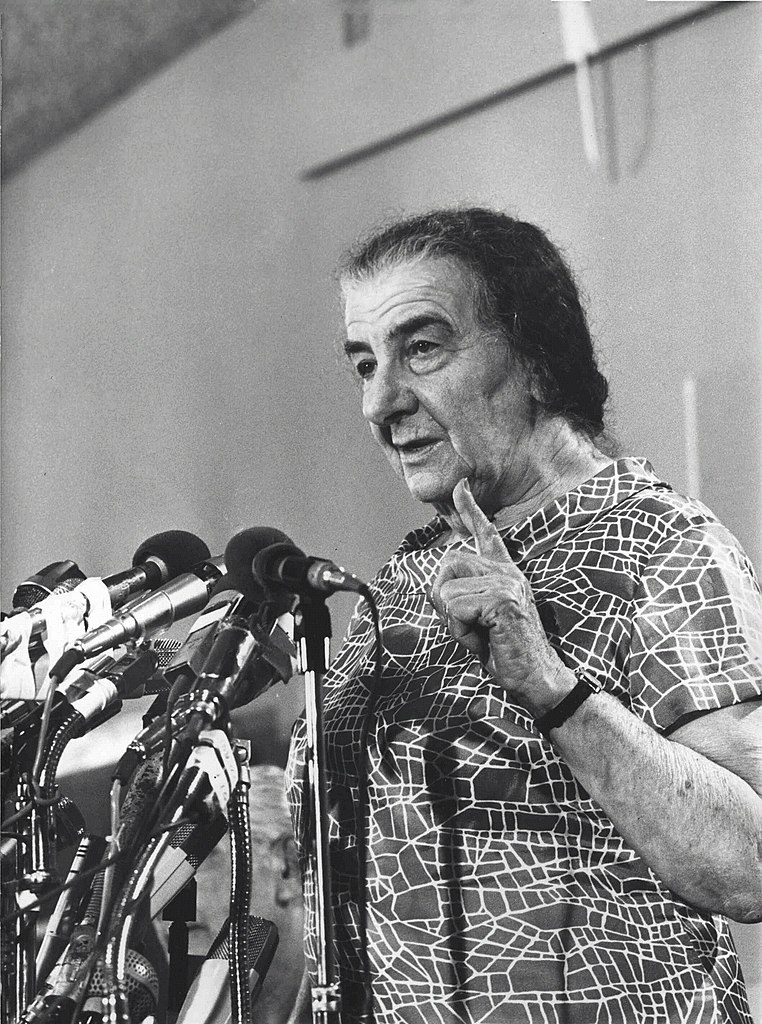

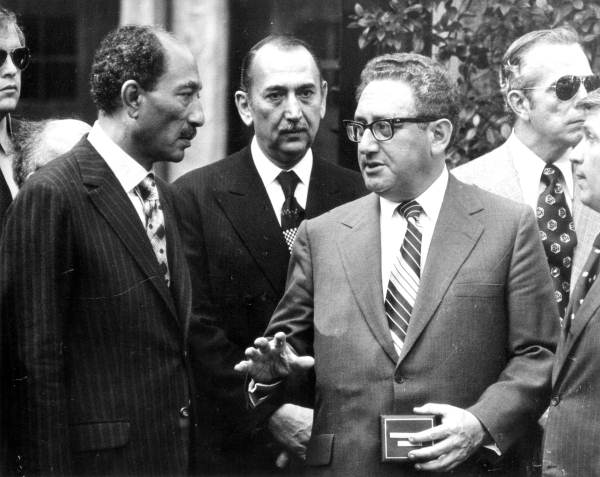

Egypt and Jordan leaned heavily on Soviet support for arms and many Arab nations welcomed Soviet aid. Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger sought to play it safe by promising Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir a resupply of weapons only after the war’s end.

The situation changed by October 12. The Soviet Union began flying weapons to Egypt and Syria. Simultaneously, Israeli offensives on both fronts stalled. The Israeli leadership became increasingly despondent and even discussed the use of nuclear weapons. These signals made it clear to the Nixon administration that aid was necessary.

Nixon authorized Operation Nickel Grass to airlift weapons to Israel. A stream of arms entered the nation while the United States made simultaneous covert reconnaissance flights and fed intelligence to Israel. Reinforced Israeli units quickly turned the tide on both the northern and southern fronts. Israeli paratroopers crossed the Suez Canal and pushed toward the outskirts of Damascus by October 15.

The Arab states, sensing failure, employed economic measures to attack Israel. On October 17, Arab oil producers cut oil production by five percent. Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister, Omar Saqqaf, visited America and warned the Nixon administration that an embargo of sales to the United States was forthcoming. Nixon attempted to assuage Saudi fears, promising to help mediate “peaceful, just, and honorable” outcomes for all parties.

Nixon quickly undercut his own promises two days later when he requested an additional $2 billion worth of arms for Israel from Congress. The request incensed Arab nations, demonstrating to them that Nixon was unlikely to mediate a balanced outcome. The same day, the Arab nations of OPEC instituted an embargo against the United States. The embargo blocked any United States importation of OPEC oil and accompanied further production cuts.

The effect of the oil embargo on the United States was profound. In the early 1970s, the price of industrial commodities was already up, materials were in short supply, and the domestic oil industry suffered from low production capacity. American oil reserves were simply not prepared for a sudden shortfall.

The embargo immediately translated into the “first oil shock” for the American public. The average American faced miles-long lines at the pump and sold-out gas stations. Other sectors of the economy reeled, with everything from tourism to consumer goods suffering increased prices. The already devalued American dollar fell further.

Fears of a global recession worried America and its allies. The Nixon administration had to justify supporting Israel in the face of a global economic downturn. The OPEC nations demanded an “evenhanded” American mediation between Israel and its neighbors to end the embargo.

The linkage between oil and mediation meant that ending the war alone would not end the embargo. Between October 19 and the end of hostilities on October 25, Israel’s armed forces routed the invaders. By October 20, Syria was out of the fight after Israel repulsed it from the Golan Heights. On October 22, a U.N.-sponsored ceasefire collapsed; Israel pressed the attack across the Suez, and by October 24, Israeli forces encircled the Egyptian Third Army.

The Nixon administration realized that the destruction of the Third Army threatened a diplomatic firestorm. The Soviet Union promised intervention if Israel destroyed the army, and Kissinger feared that failing to rein in Israel would leave the United States no means to mediate. Kissinger informed the Israeli ambassador that destroying the Third Army was “an option that does not exist.” Israel refrained from destroying the army, and on October 25, all parties of the conflict signed a ceasefire.

The oil embargo, however, continued and the Nixon administration realized it had to appeal to the Arab nations. Talks from November 1973 to January 1974 among Kissinger, the Arab leaders, and Israel led to the Egyptian-Israeli Disengagement Agreement. The Nixon administration took similar steps with Israel and Syria.

These efforts, along with Kissinger’s decision in mid-March to inform Saudi Arabia that the Nixon administration was prepared to supply new weapons to the kingdom, convinced OPEC to lift the embargo. On March 19, 1974, oil exports to the United States resumed.

The domestic ramifications of the embargo sent ripples across the American energy sector. Nixon launched Project Independence in November 1973, promoting domestic oil exploration and engaging American allies in countering the OPEC cartel. While Nixon’s efforts were insufficient to prevent another crisis during the 1979 oil shock, caused by the Iranian Revolution, strengthening domestic production allowed for a more resilient American economy.

The oil embargo also forced a reexamination of American foreign policy. The United States’ policy towards Israel diminished American power and prestige abroad, particularly by emboldening the Soviet Union. Early Israeli losses made American policymakers realize that Israel was vulnerable. Simultaneously, the willingness of nations like Egypt to pursue negotiations was a welcome surprise.

Taken together, these factors helped convince later administrations that a diplomatic outcome to the Arab-Israeli conflict was not only possible but necessary.