Almost precisely a year ago Freddie Gray died of injuries sustained while in the custody of Baltimore police. His death was one among several recent cases where African Americans have been killed by police officers, and have prompted serious discussions about policing around the country. This month historian Sarah Siff details how the problem of "policing the police" stretches back decades and is rooted in the structure of American politics itself. Our system of federalism has created a tension between rights guaranteed by the Constitution and police authority that resides at the state and local levels. Sorting out those tensions remains an unfinished part of the civil rights movement.

Listen more: A Long View of Policing in America; Teaching Civil Rights; Putting Race on Display

Read more: The War on Crime and America's Prison Crisis; The Killing of Trayvon Martin; "Big Government" in American History; The American Two-Party System; “Class Warfare” in American Politics; American Populism; Immigration Policy; Domestic Violence; and Mass Unemployment

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Federal Government and Policing the Police

This winter, my daughter’s first-grade class celebrated the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. at her elementary school in our small Midwestern town. Snippets of King’s most famous speeches and pictures of his head, crafted from brown and black construction paper, lined the school hallways. Teachers gave lessons to help young students comprehend an American past with racial segregation, and how a great leader helped to overcome it through nonviolent action and the pursuit of a dream.

As my daughter grows older, she will learn about the parts of King’s dream that have gone unfulfilled. I hope she will come to understand the true breadth of the civil rights movement—how it extends beyond the brief period she studied in elementary school, into both the past and the future.

Perhaps the most troubling unattained goal of the civil rights movement is ending police brutality and use of deadly force. The desire to be free from disproportionate police violence is as old as the civil rights movement itself. It has been a core part of the agenda of rights groups and leaders from the NAACP to Black Lives Matter.

|

“We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality,” Martin Luther King, Jr. said during his address at the March on Washington in 1963. “We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people,” reads the seventh of 10 points in the Black Panther Party Platform of 1966.

To understand how some police forces in the United States have long been able to perpetuate a resistance to the expansion of personal liberty for minorities, we should inspect the federalist roots of our government.

The permissible limits of law enforcement bodies have always been set by state and local governments, and their goals are inherently at odds with the federally derived world of civil liberties articulated in the Bill of Rights. In fact, most of the protections in the Bill of Rights did not even apply to state or local officials until the 1950s.

The U.S. government took little interest in protecting African-Americans until the Civil War. In Reconstruction-era legislation, Congress planted the seeds of federal protection that would lie dormant for decades until the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration determined to cultivate them after all.

This decision opened an era of federal activism on police brutality, including a set of Supreme Court decisions that aimed to end unconstitutional police methods by making the states observe the protections for criminal defendants outlined in the Bill of Rights.

Yet police brutality persisted, sparking riots in desperately impoverished communities throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Like the rest of civil rights history, this story is not one of ultimate victory but of ongoing struggle.

The Police Power

Over the course of U.S. history, our governments have found it difficult to regulate police behavior. By the founders’ design, most law enforcement officers’ authority is not derived from the federal government. Rather, it lies within a realm of authority known as the police power.

|

The police power is much broader than law enforcement itself. It includes authority to regulate moral life (with laws on drinking, gambling, and sex), build roads and schools, control capital and labor, and endow local governments with power. States created the vast majority of laws respecting slavery and, later, those that ensconced Jim Crow. “In truth, state governments possessed a staggering freedom of action,” historian Gary Gerstle writes in a new book on the “paradox of American government.”

In terms of protecting individual rights, the revolutionary framers were far more wary of oppression by a central state than by local majoritarian rule. In the 10th Amendment, they stipulated that powers not specifically granted to the U.S. government in the Constitution are “reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

In actually wielding these un-enumerated powers, state governments drew upon the doctrine of police power, rooted in English common law. This second theory of governance privileged the public good over individual rights, and was often at odds with the liberal Constitutional principles that guided the activities of the federal government.

Law enforcement falls squarely under the heading of these broader police powers, as the name suggests. Tasked with securing the safety of the public from criminal activities, local police forces maintain broad and often invisible power over the lives of ordinary citizens.

|

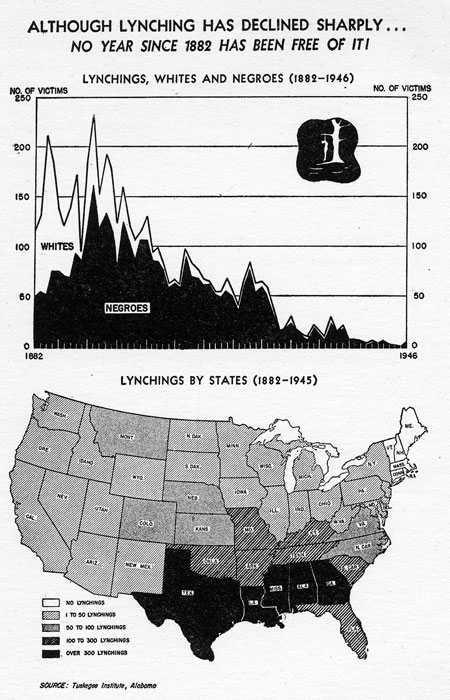

| Lynching graphic, part the “Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights,” 1946 |

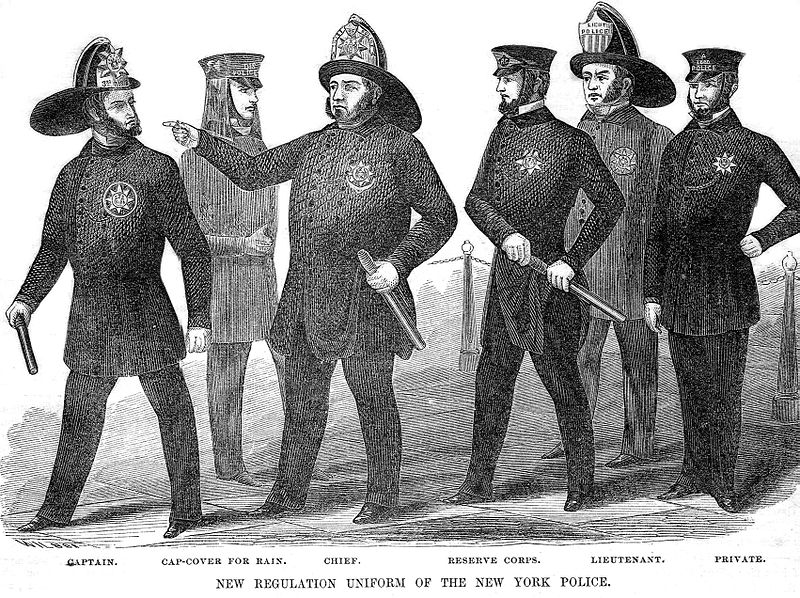

U.S. communities get the police forces that they want or are willing to permit. Whether by direct election (as a sheriff) or through an elected body such as a city council, police forces indeed derive their power from the people.

The Supreme Court has historically moved to curtail federal efforts to control or mandate the behavior of the police. At the end of the 19th century, the court struck down many provisions of the Reconstruction-era Civil Rights Acts, laws intended to provide federal enforcement of the new citizenship rights of former slaves.

States were left to govern their own race relations, with consequences that should be well known to students of U.S. history: debt peonage, disfranchisement, segregation, and lynching. The abrupt withdrawal of federal rights enforcement in the South by 1877 left a ripe environment for legislated hate and unattenuated terror. Lynch law and police brutality were often indistinguishable. Some enforcement officers in former Confederate states condoned and even carried out summary justice.

It turned out that the use of excessive force by local law enforcement officers was not solely a Southern problem. As urban populations swelled with migrants and immigrants at the turn of the century, police brutality plagued cities as well. Newspapers noted the frequency with which working-class citizens were apprehended without cause, beaten on the street or in jail, or tortured into confessing a crime.

Prisoner abuse scandals dogged police departments in Seattle, Los Angeles, and Chicago.“Not a week passes without some new instance of the injury or death of a prisoner somewhere in the United States,” the editors of the Los Angeles Herald fumed in 1910 after a resident of that city died in custody. “The police of this country apparently cannot rid themselves of a delusion they are invested with judiciary powers and can discipline as well as arrest suspects and accused persons.”

Rights organizations and the black press labored to place the ongoing problem of police brutality in the public eye and to press legal cases against officers of the law who abused their power. They chronicled police beatings and murder to little avail; state and local prosecutors and juries were rarely willing to punish them. It would take federal intervention to force a breakthrough on police brutality.

|

Quest for a Sword

The U. S. Department of Justice, working with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, can bring charges against local police under “Section 242,” one of the few pieces of civil rights law remaining from the Reconstruction era.

This part of the federal criminal code, which makes it a crime for any person acting “under color of law” to willfully abridge an individual’s constitutional rights, began its life in the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Intended by a Radical Republican Congress to provide federal enforcement of former slaves’ rights as citizens, the act’s provisions were pilloried by the Supreme Court and then left to gather dust until the 1930s by Southern Democrats and laissez-faire Republicans.

But in a characteristically creative move, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration saw in the old statutes their best chance to bring the police to heel. Using these “ancient and even archaic” statutes to force the states to respect civil liberties was a New Deal experiment, wrote political scientist Robert K. Carr in 1947.

|

Creating the civil rights unit in the Department of Justice was one of the first actions Frank Murphy (left)—a former governor of Michigan, mayor of Detroit, and U.S. attorney—took when FDR appointed him Attorney General in 1939. “Where there is social unrest … we ought to be more anxious and vigorous in protecting the civil liberties of protesting and insecure people,” Murphy told reporters just after taking office.

Murphy’s written order made it clear the unit’s main function was to prosecute local authorities for civil rights violations. He directed his staff to dust off the Reconstruction code “to determine the effect of those statutes under modern conditions in local communities.” This approach was judged more likely to succeed than asking Congress to provide a new statutory basis for policing the police.

In describing this work, Carr borrowed a metaphor from Justice Robert H. Jackson to explain the Civil Rights Section’s ideal of protecting civil rights with both a shield and a sword: “The shield … enables a person whose freedom is endangered to invoke the Constitution by requesting a federal court to invalidate the state action that is endangering his rights. The sword is a positive weapon wielded by the federal government, which takes the initiative in protecting helpless individuals by bringing criminal charges against persons who are encroaching upon their rights.”

Using this sword, the Civil Rights Section indicted Claude Screws, a Georgia sheriff who had beaten a handcuffed, unarmed black man to a bloody pulp in full public view and dragged him into a jail cell. Screws called an ambulance several hours later, but the young auto mechanic Robert Hall died moments after he was admitted, on January 30, 1943.

The nauseating details of Hall’s death, the fabricated arrest warrant used to apprehend him, the numerous eyewitnesses, and evidence of the sheriff’s intent to harm Hall amounted to an ideal case for testing Section 242. The state of Georgia refused to prosecute Screws for Hall’s murder, so Murphy charged the sheriff with a federal crime.

|

“Armed with an old law and a new zeal,” as one contemporary observer noted, the Civil Rights Section prosecuted Screws and two accomplices for denying Hall his right not to be deprived of life without due process of law—a protection derived from the 14th Amendment, directed squarely at the states.

From the outset, the case looked good. All three men were convicted by an Albany, Georgia jury and the decision was upheld on appeal by the Fifth Circuit Court. When the defendants’ appeal reached the Supreme Court, however, the fate of Section 242 would be decided. Would the court provide a narrow interpretation as it had for other Reconstruction-era civil rights statutes? Worse, would it invalidate the law altogether?

The 1945 decision in Screws v. United States did neither, much to the relief of the Civil Rights Section lawyers. Still, the results of the case were somewhat mixed.

One major issue had been to establish what the phrase “under color of law” meant. It had long been construed as “legally,” meaning it could not apply to the clearly illegal actions of the Screws defendants. Earlier Supreme Court decisions had held that the 14th Amendment was enforceable against the states, but not against individuals acting on their own; indeed, this rationale was part of the defense’s argument.

The decision in Screws held that the three policemen were acting “under color of law”—in their official capacities as law enforcement officers—when they arrested and detained Hall.

Three dissenting justices argued that this interpretation of the phrase would fundamentally alter the balance of power between the federal and state governments by rendering “every lawless act of the policeman on the beat” a federal crime.

The defense also argued that the law was vague; the “due process” rights the police were charged with violating were not clearly defined. The court answered this by emphasizing the law’s requirement that the defendant acted “willfully” to deprive the victim of constitutional rights—with specific intent—a high standard of proof.

The officers were retried and acquitted by a jury that was, this time, instructed at length on the willfulness issue. Rendered a free man, Sheriff Screws soon won election to the Georgia State Senate.

|

A majority of commentators, both at the time and today, look at the Screws case as a setback for civil rights jurisprudence, when the difficult standard of willfulness was added to the prosecution’s burden of proof. But some argue that the decision actually marked, in U.S. Circuit Judge Paul J. Watford’s (left) words, “the birth of federal civil rights enforcement.” As he said in 2014, the most immediate effect of the decision was to secure a federal role to combat police brutality toward minorities.

“Had the statute instead been struck down, the power of the federal government to prosecute such abuses would have been drastically curtailed,” Watford said. “No other statute remained that would have allowed the federal government to prosecute violations of the most basic rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.”

At the time of the ruling (1945), the editors of the Chicago Daily Tribune praised it as a victory for civil rights, writing that the high court had “rediscovered the 14th Amendment.” The Civil Rights Section “has just been given a charter—oddly enough, an 80 year old charter—upon which to proceed against such police officers as Screws,” they wrote. “The people of this country, we suspect, will welcome the decision for the means it may afford of ending a dark chapter in law enforcement in this country.”

“We Charge Genocide”

Following the end of World War II, the U.S. government was increasingly sensitive to international criticism of domestic racial tensions, the “American dilemma” of liberal values coexisting with deep oppression.

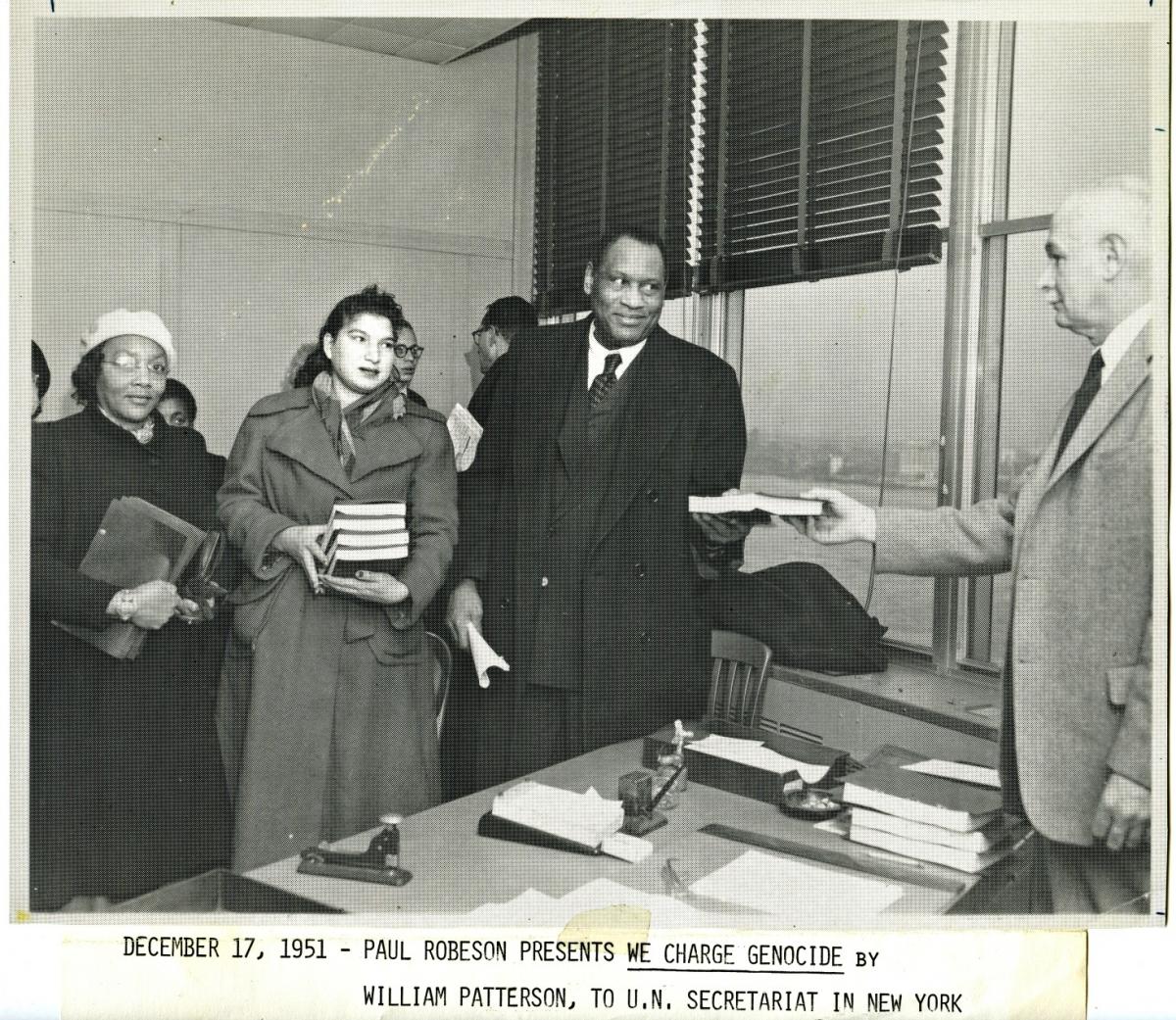

Capitalizing on this atmosphere in 1951, the Civil Rights Congress—a leftist rights group with roots in organized labor—presented “We Charge Genocide” to the United Nations in Paris. The book-length report offered summaries of hundreds of cases of lynching and police brutality from 1945 to 1951, as well as a rationale for why the U.S. government should be held accountable for the deaths under the terms of the UN’s Genocide Convention.

Among these assertions, it drew a direct line from lynching to contemporary policing:

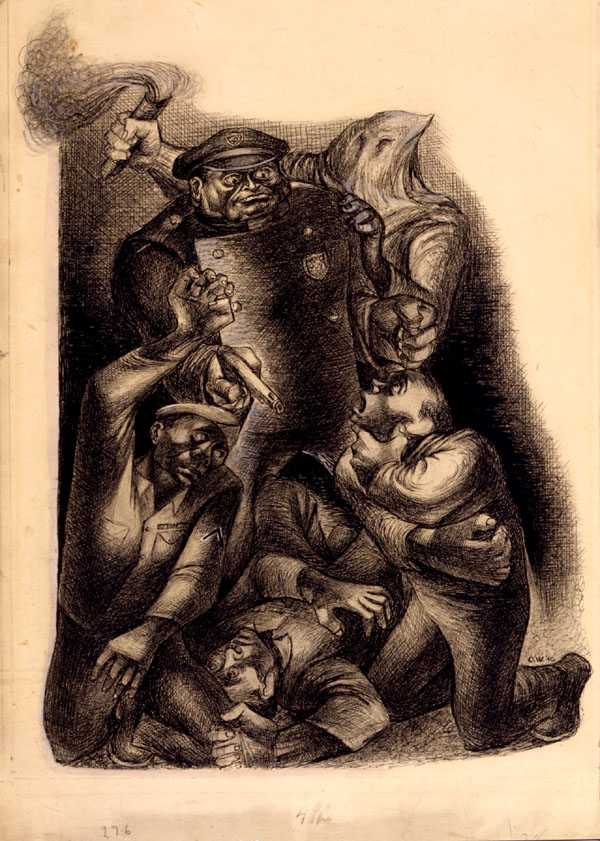

Once the classic method of lynching was the rope. Now it is the policeman’s bullet. To many an American the police are the government, certainly its most visible representative. We submit that the evidence suggests that the killing of Negroes has become police policy in the United States and that police policy is the most practical expression of government policy.

|

Signatories of “We Charge Genocide” included W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, William Patterson, and relatives of murdered black citizens. Its sponsoring organization, the Civil Rights Congress was peopled with leftist activists, labor organizers, and members of the Communist Party-USA. The State Department moved to suppress the report, and the United Nations never formally acknowledged its receipt. Activists’ passports were revoked. A few years later, the Civil Rights Congress would collapse under anti-communist pressure.

Many scholars have pointed out the ways anti-communism damaged the civil rights movement. But the flip side of the Cold War record is too often forgotten: the incorporation of the Bill of Rights to the states.

Memories of World War II and the ideological battle with the Soviets rendered the “Gestapo tactics” of local police more distasteful to the public as well as the justices. Through the middle of the century, the Supreme Court grew less and less willing to allow states to decide for themselves whether their police forces must protect the guarantees offered to criminal suspects in the Bill of Rights.

Little recognized as landmark victories for the civil rights movement—though in fact they were—a series of cases aimed to control police conduct and thereby extend the many constitutional protections for accused criminals. These rights include freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures, a privilege against self-incrimination, and protection against cruel and unusual punishments.

Prominent examples of these rulings are Mapp v. Ohio (1961) which forbade the use in court of evidence gotten through unconstitutional searches; and Miranda v. Arizona (1966), which required police to remind defendants of their rights to have a lawyer and refuse to give testimony against themselves.

Disproportionately policed and arrested, minorities were also far more likely to have their rights as criminal defendants violated. Thus rights leaders hailed these court decisions as victories for their people, just as they had hailed Brown v. Board of Education.

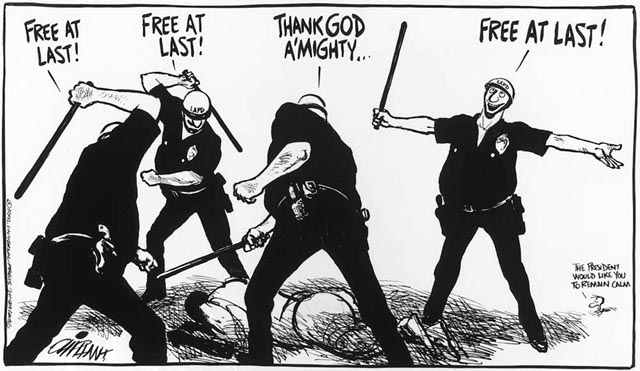

And just as state governments implemented policies of massive resistance against school integration, law enforcement bodies resisted reforms to their systems of criminal justice.

In Los Angeles, for example, Police Chief William H. Parker shielded his notoriously brutal and racist police force from court directives to stop their violent witness interrogations and to start using search warrants. Parker railed against “lenient” judges who threw out illegally obtained evidence and campaigned loudly for state laws to circumvent the court rulings.

|

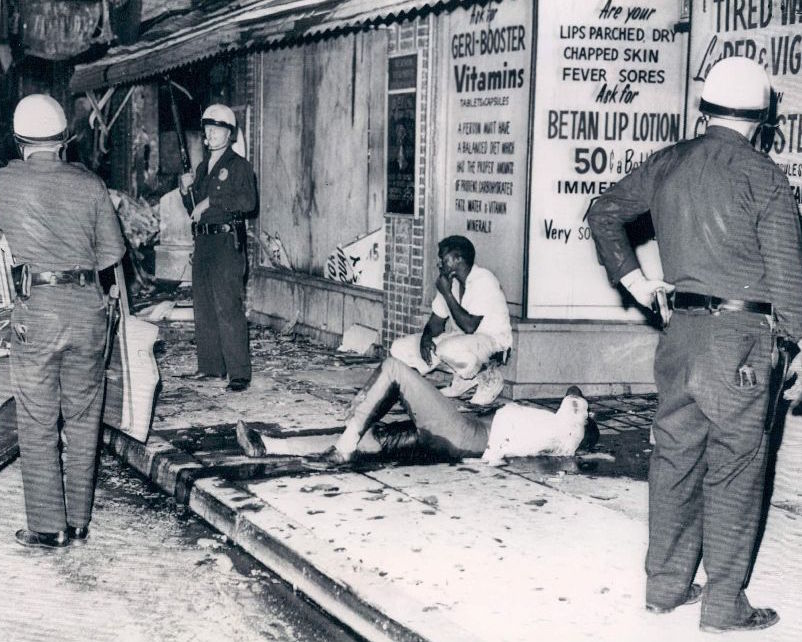

In the case of Los Angeles, the dismal relations between city police and minority communities had been evident for more than a decade when riots erupted in the Watts neighborhood in 1965. Drawing national media attention, the Watts riots and the brute force used in the same year against protesters in Selma, Alabama, presented two unsavory sides of the same civil rights issue.

Nonviolent protesters in the Deep South confronted the police brutality issue in the most literal sense, placing their bodies in harm’s way. Organizers became police targets. The notion of police as guardians of the public and impartial enforcers of the law grew more difficult to maintain as violent images from both ends of the country played to mass audiences on the nightly news.

Urban Disorder and Federal Response

Police violence was often the match that ignited urban riots in the ’Sixties. In July 1964, Harlem sank into chaos after a veteran police lieutenant shot dead a 15-year-old black male. In Newark in 1967, the arrest and beating of a black cab driver led to an angry protest outside the police station, which morphed into several days of burning, looting, and police and civilian casualties. Detroit’s fateful 1967 riot that claimed 43 lives and shut down the city began with a police raid on a party and the decision to detain and transport dozens of revelers.

The Lyndon Johnson administration responded to the riots by calling for programs that would attack the root causes of poverty and despair in the cities. He said his War on Poverty was also a War on Crime. Richard Nixon ran campaign ads featuring scenes from the riots and promising to impose order.

Johnson created a National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner Commission, which found in a 20-city survey that police practices ranked as a “deeply held grievance” among rioters at the highest level of intensity, followed closely by unemployment and poor housing. Members of the Civil Rights Commission, also a federal advisory body, had been reporting this problem for years. Dwight Eisenhower had established the commission to monitor and recommend policy related to civil-rights issues. Its first major report, rendered in 1961, included riveting accounts of police brutality and death cases. It also detailed the ongoing struggles of the Civil Rights Division through the 1950s to prosecute police who beat, killed, and otherwise trampled the rights of black Americans.

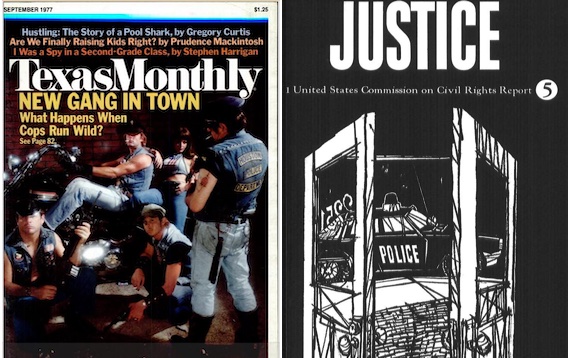

Following a string of shooting and beating deaths by the Houston Police Department in the mid-1970s, Texas Monthly magazine published this issue featuring a photo illustration of police officers as members of a gang (left). "Justice" was one of five civil-rights issues studied by the Civil Rights Commission in this 1961 report (cover pictured). It focused narrowly and frankly on the problem of continued police brutality toward minorities (right).

The Civil Rights Commission continued its work during the 1960s and 1970s. It helped the civil rights movement and liberal administrations secure victories in school desegregation, voting rights, and fair employment. But the persistence of police brutality confounded and frustrated the commission.

Highly publicized episodes of police misconduct during the 1970s revealed cracks in the foundations of the nation’s law-and-order regime under Nixon.

Augusta, Georgia police killed three rioters and three bystanders, all black, in early 1970. Responding to destructive student demonstrations on campus, Mississippi State Troopers fired 250 rounds into a women’s dorm at Jackson State College in May 1970, killing two young black men. Protests rippled through New York in 1972 after police in Staten Island shot dead an 11-year-old fleeing a stolen car on foot. Black leaders in Memphis, a city long plagued by police brutality, called for a boycott on white businesses after police shot dead three black suspects aged 14, 17, and 22 in separate incidents over a 12-day period in 1972.

A rash of incidents in the Southwest through the 1970s proved Mexican Americans were also disproportionately deprived of civil liberties and subjected to police violence. In 1979, the New York Times noted that weak results from President Jimmy Carter’s Justice Department in prosecuting Texas police in death and brutality cases was a betrayal of Hispanic support in the 1976 election.

Carter, at least, supported the continuing existence of the Civil Rights Commission. By 1980, New York, Miami, Houston, and Philadelphia topped a list of places where “incidents of excessive use of force by police have triggered widespread tension and community unrest,” according to the commission.

|

Today we have a different list: Chicago, Baltimore, Minneapolis, Cleveland. All are sites of recent unrest originating in killings of unarmed black males by police officers.

The patterns of violence and disorder were the same then as they are now. Police were summoned to a run-down neighborhood. A black suspect resisted arrest (or fled) and officers responded with deadly force. Community members, anguished and with nothing much to lose, took to the streets in protest, their civil disobedience frequently morphing into riots.

To end this violence, the civil rights commissioners in 1980 pleaded for reforms, such as requiring that police forces reflect the demographic makeup of their jurisdictions, modifying federal code to make it easier to prosecute officers for misconduct, and responding more effectively to brutality complaints.

“Violations of the civil rights of our people by some members of police departments [are] a serious national problem,” they wrote, urging steps to “make it clear that the Federal Government intends to act in an increasingly vigorous manner to end intolerable practices.”

By the time the Civil Rights Commission presented its report on police practices to Carter, the nation was becoming less sympathetic to civil rights issues. President-elect Ronald Reagan soon moved to curtail the commission’s funding and narrow its scope, replacing several commissioners with conservative allies focused on implementing “colorblind” policies such as reversing affirmative action. In what was surely a compromise, the commission titled its 1983 report, “Who’s Guarding the Guardians?”

The Politics of Oversight

The first significant legislation on the federal oversight of state and local police is contained in the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, the same legislation that has recently made presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and former President Bill Clinton targets of criticism for the bill’s widening and fortification of the carceral state.

|

The same legislation, however, authorizes the Department of Justice to step in when a police force seems to engage in a “pattern or practice” that deprives people of constitutional rights. The federal government has conducted wide-ranging investigations of a handful of state police and dozens of local police forces under this law, including Los Angeles, New Orleans, Chicago, New York, Detroit, and Cincinnati.

One former lawyer with the Civil Rights Division recalled that such a law had been “always on the wish list” but only became possible after the Rodney King beating incident in Los Angeles in 1991.

Yet when confronted about the crime bill, neither Clinton has reminded voters that the act also contained these landmark provisions for reforming police departments—provisions that have been used far more by Democratic than by Republican administrations. This suggests policing the police is not a winning issue for the general-election voter.

The history of police brutality highlights its durability as a social problem and a political issue. Moreover, ending police brutality is an unfinished chapter of the civil rights movement. Activists still want to win for minorities freedom from the oppression of fear caused by this potent, yet too-often misused, form of local power.

Berry, Mary Frances. And Justice for All: The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and the Continuing Struggle for Freedom in America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

Carr, Robert K. Federal Protection of Civil Rights: Quest for a Sword. Cornell Studies in Civil Liberty, edited by Robert E. Cushman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1947.

Gerstle, Gary. Liberty and Coercion: The Paradox of American Government from the Founding to the Present. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Goluboff, Risa L. The Lost Promise of Civil Rights. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

McMahon, Kevin J. Reconsidering Roosevelt on Race: How the Presidency Paved the Road to Brown. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Nelson, Jill, ed. Police Brutality: An Anthology. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2000.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Justice. 1961 Commission on Civil Rights Report, Washington, DC.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Who Is Guarding the Guardians? A Report on Police Practices. Washington, DC, 1983.

U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. “Criminal Section Selected Case Summaries.”